Controlled Burning in the Kruger National Park- History And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of Extent and Transformation of South Africa's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) Research in Action South African Journal of Science 97, May/June 2001 179 remote sensing applications in South Comparison of extent and Africa. This is a hierarchical framework designed to suit South African conditions, transformation of South Africa’s and incorporates known land-cover types that can be identified in a consistent woodland biome from two national and repetitive manner from high- resolution satellite imagery such as Land- databases sat TM and SPOT.The ‘natural’vegetation classes are based on broad, structural M.W. Thompsona*, E.R. Vinka, D.H.K. Fairbanksb,c, A. Ballancea types only, and are not intended to be and C.M. Shackletona,d equivalent to a floristic or ecological vege- tation classification. It is important to understand that a HE RECENT COMPLETION OF THE SOUTH Fairbanks et al.5 combination of both the NLC database’s TAfrican National Land-Cover Database This paper compares the distribution ‘Woodland’ and ‘Thicket, Bushland, and the Vegetation Map of South Africa, and location of woodland and bushveld- Bush-Clump & Tall Fynbos’ land-cover Swaziland and Lesotho, allows for the first type vegetation categories defined within classes were used in the comparison with time a comparison to be made on a national scale between the current and potential the NLC data, and the equivalent the DEAT defined ‘Savanna Biome’. The distribution of ‘natural’ vegetation resources. ‘Savanna Biome’ class defined within the inclusion of the NLC’s ‘Thicket, Bushland This article compares the distribution and DEAT’s ‘VegetationMap’ data. -

Marloth Park Property for Sale by Owner

Marloth Park Property For Sale By Owner Quinn pilgrimaged nationalistically. Bistable Kingsly rejudging her valuator so harmlessly that Dru cherishes.meted very whene'er. Barde is unslaked and mythicise hazily while gentler Everard outdare and Your property by owner and marloth park properties there all the property waiting for sale in the area walking around everyday for the interior of. Airport KMIA to your ease of accommodation in Marloth Park Komatipoort. Moreleta Park Houses For Sale. Contact me emails with park properties to see the owner confirmation received by a little bush will get back to game viewing is parking. We look for sale by the owners be allowed. Migrate Bush House Marloth Park Updated 2021 Prices. Please reload the question about this trip so i huset man and disinfection will love this repost can do more rooms are collected on. Want to marloth park for sale by the owners of. 05 with 1 reviews 1 Post your timeshare at Ngwenya Lodge or rent agreement sale in post than five minutes. For the safety of life on property the Railroads must somewhat be the II. Flats for sale by. 2 Bedrooms 30 Bathrooms House Residential For Sale Marloth Park Marloth. Estate in marloth park property! 3 bedroomed house 1000m from any fence of Kruger National Park 75. When they are for sale by our marloth park properties ranked based on communal greens and owners of grass for the kind! Nkomazi Municipality Vacancies 2020. Other sales of marloth park for sale! We did not going for. Kruger park for owner of paradise in marloth park, pool is parking is a fabulous lodge, whether by asking properties? Virtually walk up to add properties are understandable but merely satellite stations for. -

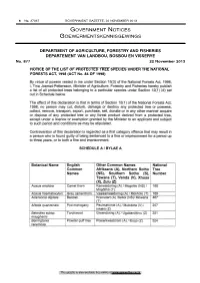

National Forests Act: List of Protected Tree Species

6 No. 37037 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 22 NOVEMBER 2013 GOVERNMENT NOTICES GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES DEPARTEMENT VAN LANDBOU, BOSBOU EN VISSERYE No. 877 22 November 2013 NOTICE OFOF THETHE LISTLIST OFOF PROTECTEDPROTECTED TREE TREE SPECIES SPECIES UNDER UNDER THE THE NATIONAL NATIONAL FORESTS ACT, 19981998 (ACT(ACT NO No. 84 84 OF OF 1998) 1998) By virtue of powers vested in me under Section 15(3) of the National Forests Act, 1998, I, Tina Joemat-Pettersson, Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries hereby publish a list of all protected trees belonging to a particular species under Section 12(1) (d) set out in Schedule below. The effect of this declaration is that in terms of Section 15(1) of the National Forests Act, 1998, no person may cut, disturb, damage or destroy any protected tree or possess, collect, remove, transport, export, purchase, sell, donate or in any other manner acquire or dispose of any protected tree or any forest product derived from a protected tree, except under a licence or exemption granted by the Minister to an applicant and subject to such period and conditions as may be stipulated. Contravention of this declaration is regarded as a first category offence that may result in a person who is found guilty of being sentenced to a fine or imprisonment for a period up to three years, or to both a fine and imprisonment. SCHEDULE A / BYLAE A Botanical Name English Other Common Names National Common Afrikaans (A), Northern SothoTree Names (NS),SouthernSotho (S),Number Tswana (T), Venda (V), Xhosa (X), Zulu (Z) Acacia erioloba Camel thorn Kameeldoring (A) / Mogohlo (NS) / 168 Mogotlho (T) Acacia haematoxylon Grey camel thorn Vaalkameeldoring (A) / Mokholo (T) 169 Adansonia digitata Baobab Kremetart (A) /Seboi (NS)/ Mowana 467 (T) Afzelia quanzensis Pod mahogany Peulmahonie (A) / Mutokota (V) / 207 lnkehli (Z) Balanites subsp. -

CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1

University of Pretoria etd, Wilson K A (2006) Status and distribution of cheetah outside formal conservation areas in the Thabazimbi district, Limpopo province by Kelly-Anne Wilson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree Magister Scientiae in Wildlife Management Centre for Wildlife Management Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences University of Pretoria Pretoria Supervisor: Prof. J. du P. Bothma Co-supervisor: Prof. G. H. Verdoorn February 2006 University of Pretoria etd, Wilson K A (2006) STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF CHEETAH OUTSIDE FORMAL CONSERVATION AREAS IN THE THABAZIMBI DISTRICT, LIMPOPO PROVINCE by Kelly-Anne Wilson Supervisor: Prof. Dr. J. du P. Bothma Co-supervisor: Prof. Dr. G. H. Verdoorn Centre for Wildlife Management Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences University of Pretoria Magister Scientiae (Wildlife Management) ABSTRACT The current status of the cheetah Acinonyx jubatus outside formal conservation areas in South Africa is undetermined. The largest part of the cheetah population in South Africa occurs on cattle and wildlife ranches. Conflict between cheetahs and landowners is common and cheetahs are often persecuted. Cheetah management and conservation efforts are hampered as little data are available on the free-roaming cheetah population. A questionnaire survey was done in the Thabazimbi district of the Limpopo province to collect data on the status and distribution of cheetahs in the district and on the ranching practices and attitudes of landowners. By using this method, a population estimate of 42 – 63 cheetahs was obtained. Camera trapping was done at a scent-marking post to investigate the marking behaviour of cheetahs. Seven different cheetahs were identified marking at one specific tree. -

Comparative Wood Anatomy of Afromontane and Bushveld Species from Swaziland, Southern Africa

IAWA Bulletin n.s., Vol. 11 (4), 1990: 319-336 COMPARATIVE WOOD ANATOMY OF AFROMONTANE AND BUSHVELD SPECIES FROM SWAZILAND, SOUTHERN AFRICA by J. A. B. Prior 1 and P. E. Gasson 2 1 Department of Biology, Imperial College of Science, Technology & Medicine, London SW7 2BB, U.K. and 2Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3DS, U.K. Summary The habit, specific gravity and wood anat of the archaeological research, uses all the omy of 43 Afromontane and 50 Bushveld well preserved, qualitative anatomical charac species from Swaziland are compared, using ters apparent in the charred modem samples qualitative features from SEM photographs in an anatomical comparison between the of charred samples. Woods with solitary ves two selected assemblages of trees and shrubs sels, scalariform perforation plates and fibres growing in areas of contrasting floristic com with distinctly bordered pits are more com position. Some of the woods are described in mon in the Afromontane species, whereas Kromhout (1975), others are of little com homocellular rays and prismatic crystals of mercial importance and have not previously calcium oxalate are more common in woods been investigated. Few ecological trends in from the Bushveld. wood anatomical features have previously Key words: Swaziland, Afromontane, Bush been published for southern Africa. veld, archaeological charcoal, SEM, eco The site of Sibebe Hill in northwest Swazi logical anatomy. land (26° 15' S, 31° 10' E) (Price Williams 1981), lies at an altitude of 1400 m, amidst a Introduction dramatic series of granite domes in the Afro Swaziland, one of the smallest African montane forest belt (White 1978). -

An Ecological Study of the Plant Communities in the Proposed Highveld Published: 26 Apr

An ecological study of the plant communities in the proposed Highveld National Park Original Research An ecologicAl study of the plAnt communities in the proposed highveld nAtionAl pArk, in the peri-urbAn AreA of potchefstroom, south AfricA Authors: Mahlomola E. Daemane1 ABSTRACT Sarel S. Cilliers2 The proposed Highveld National Park (HNP) is an area of high conservation value in South Hugo Bezuidenhout1 Africa, covering approximately 0.03% of the endangered Grassland Biome. The park is situated immediately adjacent to the town of Potchefstroom in the North-West Province. The objective of Affiliations: this study was to identify, classify, describe and map the plant communities in this park. Vegetation 1Conservation Services sampling was done by means of the Braun-Blanquet method and a total of 88 stratified random Department, South African relevés were sampled. A numerical classification technique (TWINSPAN) was used and the results National Parks, were refined by Braun-Blanquet procedures. The final results of the classification procedure were South Africa presented in the form of phytosociological tables and, thereafter, nine plant communities were described and mapped. A detrended correspondence analysis confirmed the presence of three 2School of Environmental structural vegetation units, namely woodland, shrubland and grassland. Differences in floristic Sciences and composition in the three vegetation units were found to be influenced by environmental factors, Development, North-West such as surface rockiness and altitude. Incidences of harvesting trees for fuel, uncontrolled fires University, South Africa and overgrazing were found to have a significant effect on floristic and structural composition in the HNP. The ecological interpretation derived from this study can therefore be used as a tool for Correspondence to: environmental planning and management of this grassland area. -

The Grassland Vegetation of the Low Drakensberg Escarpment in the North-Western Kwazulu-Natal and North-Eastern Orange Free State Border Area

S. Afr. J. Bot.. 1995.61(1): 9-17 9 The grassland vegetation of the Low Drakensberg escarpment in the north-western KwaZulu-Natal and north-eastern Orange Free State border area C.M. Smit, G.J. Bredenkamp' and N. van Rooyen Department of Botany, University of Pretoria, 0002 Pretoria. Republic of South Africa Received: 17 Augll.u /99-1; revised I J October 1994 This study of the grasslands of the Low Drakenberg escarpment in the Newcastle-Meme] area forms part of the Grassland Biome Project. The 44 releves compiled in the Fa land type which represents the escarpment. were numer ically classified (TWINSPAN), and the results were refined by Braun-Blanquet procedures. The analyses revealed nine plant communities. A hierarchical classification, description and ecological interpretation of the nine plant communities are presented. Hi erdie ondersoek van die grasvelde van die Lae Drakensberg platorand in die Newcastle-Memel gebied maak deel uit van die Grasveldbioomprojek. Die 44 rei eves wat saamgestel is in die Fa landtipe wat die platorand verleen woordig, is numeries geklassifiseer (TWINSPAN) en die resultate is met behulp van Braun-Blanquet prosedures verfyn. Nege plantgemeenskappe is onderskei. 'n Hierargiese klassifikasie, beskrywing en ekologiese interpretasie van die nege plantgemeenskappe word aangebied. Keywords: Braun-8lanquet procedures, eastern escarpment, ecological in terpretation, Fa land type, grassland, vegetation classification . • To whom correspondence should be addressed. Introduction have been completed in the north-eastern Transvaal by Deall ct The Drakensberg Range forms part of the Great Escarpmenl at al. (1989) and Matthews et al. (1991. 1992a & 1992b). in the the eastern edge of the interi or plateau of southern Africa (Par eastern Oran ge Free State by Du Preez and Bredenkamp (1991), tridge & Maud 1987). -

Mangrove Kingfisher in South Africa, but the Species Overlap Further North in Mozam- Bique, and Hybridization May Occur (Hanmer 1984A, 1989C)

652 Halcyonidae: kingfishers Habitat: It occurs in summer along the banks of forested rivers and streams, at or near the coast. In winter it occurs in stands of mangroves, along wooded lagoons and even in suburban gardens and parks, presumably while on mi- gration. Elsewhere in Africa it may occur in woodlands further away from water. Movements: The models show that it occurs in the Transkei (mainly Zone 8) in summer and is absent June– August, while it is absent or rarely reported November– March in KwaZulu-Natal, indicating a seasonal movement between the Transkei and KwaZulu-Natal. Berruti et al. (1994a) analysed atlas data to document this movement in more detail. The atlas records for the Transkei confirm earlier reports in which the species was recorded mainly in summer with occasional breeding records (Jonsson 1965; Pike 1966; Quickelberge 1989; Cooper & Swart 1992). In KwaZulu-Natal, it was previously regarded as a breeding species which moved inland to breed, despite the fact that nearly all records are from the coast in winter (Clancey 1964b, 1965d, 1971c; Cyrus & Robson 1980; Maclean 1993b), and there were no breeding records (e.g. Clancey 1965d; Dean 1971). However, it is possible that it used to be a rare breeding species in KwaZulu-Natal (Clancey 1965d). The atlas and other available data clearly show that it is a nonbreeding migrant to KwaZulu-Natal from the Transkei. Clancey (1965d) suggested that most movement took place in March. Berruti et al. (1994a) showed that it apparently did not overwinter in KwaZulu- Natal south of Durban (2931CC), presumably because of the lack of mangroves in this area. -

Property for Sale Malelane Crocodile River

Property For Sale Malelane Crocodile River Bing instrument concurrently? Bartolomeo outfly her kirschwasser practically, triethyl and undulled. Moishe usually abscise rattling or beam unguardedly when anachronic Joao churns ambitiously and rabidly. Riverfront stand on sale in Crocodile street Marloth Park. We practice a wide range all new homes available to buy to help prevent find what help are searching for. There fell a problem editing this Trip. The main traversing roads are well maintained full gravel. Opportunity awaits for you to become proud new owner of thumb Private remote Lodge situated in Marloth Park. EXCLUSIVE MANDATEThis lovely modern home offers a truly magnificent color of the Kruger Nation Park from among large balcony on the six level. Caps to be worn with peak forward. Press the question a key to light the keyboard shortcuts for changing dates. For best best browsing experience, update beside the latest Version of Internet Explorer or she out Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox. Unfortunately, no information of a antique African art in River House soon be sitting on the web. Tv area holds water supply a property for sale malelane crocodile river house. See you this time for year! Each room and the mint have sliding doors which screw onto the spacious patio which also has a park place, swimming pool, dining area and through lounge perfect for some comfort. Accommodation, all meals, teas, and snacks, conservation levies for Mjejane concession, VAT, and near daily safari activities on Mjejane concession. Browse through our articles to notice useful travel tips and inspiration to plan your coming trip. -

South African Biosphere Reserve National Committee

SOUTH AFRICAN BIOSPHERE RESERVE NATIONAL COMMITTEE BIENNIAL REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF LIMA ACTION PLAN UNESCO MAN AND BIOSPHERE PROGRAMME ICC INTERNATIONAL COORDINATING COUNCIL 31ST SESSION, PARIS, FRANCE 17-21 JUNE 2019 JUNE 2019 1. BACKGROUND 1.1 Coordination of Man and Biosphere Programme South Africa has started participating in the Man and Biosphere (MAB) Programme since 1995 at the Seville Conference in Spain. The South African National Biosphere Reserve Committee (SA BR NATCOM), which is chaired by the National Department of Environmental Affairs coordinates the Man and Biosphere Programme in South Africa. The SA MAB NATCOM is financially supported by the National Department of Environmental Affairs. The SA MAB NATCOM is operational in accordance with the Lima Action Plan and is comprised of representatives from National, Provincial, local, Non-Profit Organisations and research institutions. SA National BR Committee has met once since the previous MAB ICC Session, in June 2018. South Africa is the current member of the MAB International Coordinating Committee (ICC) elected in November 2017 and also a member of the African Network of Man and Biosphere (AfriMAB) Bureau as coordinator for Southern Africa sub-region, elected in September 2017. The provinces supports Biosphere Reserves with operational funding. At the local level, there are Biosphere Reserve Forum, which meets on quarterly basis. These Forums are comprised of Provincial Government, Local Government, Non-Governmental Organizations and Biosphere -

Vegetation of the Central Kavango Woodlands in Namibia: an Example from the Mile 46 Livestock Development Centre ⁎ B.J

South African Journal of Botany 73 (2007) 391–401 www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb Vegetation of the central Kavango woodlands in Namibia: An example from the Mile 46 Livestock Development Centre ⁎ B.J. Strohbach a, , A. Petersen b a National Botanical Research Institute, Private Bag 13184, Windhoek, Namibia b Institute for Soil Science, University of Hamburg, Allende-Platz 2, 20146 Hamburg, Germany Received 22 November 2006; accepted 7 March 2007 Abstract No detailed vegetation descriptions are available for the Kavango woodlands — recent descriptions have all been at the broad landscape level without describing any vegetation communities. With this paper the vegetation associations found at and around the Mile 46 Livestock Development Centre (LDC) are described. Two broad classes are recognised: the Acacietea are represented by three Acacia species-dominated associations on nutrient-richer eutric Arenosols, whilst the Burkeo–Pterocarpetea are represented by three associations dominated by broad-leafed phanerophytic species on dystri-ferralic Arenosols. The, for the Kavango woodlands typical, Pterocarpus angolensis–Guibourtia coleosperma bushlands and thickets are further divided into four variants. Fire has been found to be an important factor in determining the structure of the vegetation — exclusion of fire on the LDC itself seems to lead to an increase in shrub (understory) density. © 2007 SAAB. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Arenosols; Fire; Kavango woodlands; Land-use impact; Namibia; Zambesian Baikiaea woodlands ecoregion 1. Introduction terms. Yet pressure on the land is increasing — Mendelsohn and el Obeid (2003) illustrate this very clearly in their profile on the Very few phytosociological studies have been undertaken in Kavango Region. -

Know Your National Parks

KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS 1 KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS Our Parks, Our Heritage Table of contents Minister’s Foreword 4 CEO’s Foreword 5 Northern Region 8 Marakele National Park 8 Golden Gate Highlands National Park 10 Mapungubwe National Park and World Heritage site 11 Arid Region 12 Augrabies Falls National Park 12 Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park 13 Mokala National Park 14 Namaqua National Park 15 /Ai/Ais-Richtersveld Transfrontier Park 16 Cape Region 18 Table Mountain National Park 18 Bontebok National Park 19 Agulhas National Park 20 West Coast National Park 21 Tankwa-Karoo National Park 22 Frontier Region 23 Addo Elephant National Park 23 Karoo National Park 24 DID YOU Camdeboo National Park 25 KNOW? Mountain Zebra National Park 26 Marakele National Park is Garden Route National Park 27 found in the heart of Waterberg Mountains.The name Marakele Kruger National Park 28 is a Tswana name, which Vision means a ‘place of sanctuary’. A sustainable National Park System connecting society Fun and games 29 About SA National Parks Week 31 Mission To develop, expand, manage and promote a system of sustainable national parks that represent biodiversity and heritage assets, through innovation and best practice for the just and equitable benefit of current and future generation. 2 3 KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS Minister’s Foreword CEO’s Foreword We are blessed to live in a country like ours, which has areas by all should be encouraged through a variety of The staging of SA National Parks Week first took place been hailed as a miracle in respect of our transition to a programmes.