Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

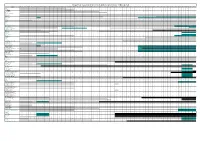

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout Those channels whose viewing data is not shown below as being available are included in the channel group ‘Other STV’ From 28 From 11 From 27 From 19th From 28th From 26th From 27th From 26th From 25th From 24th From 1st From 31st Channel Dec 2003 July 2004 Feb 2005 June 2005 Aug 2005 Nov 2006 May 2007 Aug 2007 Nov 2007 Feb 2008 June 2008 May 2009 111 Hits 9 Adults Only Adventure One AIR Audio Channels Al Jazeera Animal Planet 9999 9999999 Antenna Arena TV 999999999999 Arena TV+2* * 999999999 Art Arabic Aurora Community Channel* * Aust Christian Channel BBC World 999 Biography Channel* * 9999999 Bloomberg Television 999 Boomerang 99999 Box Office* * Box Office Adults Only Select* * Box Office Main Event* * Box Office Preview* * Cartoon Network 999999999999 Channel V Channel V2 999999 Club (V) CNBC 999999999999 CNN International Comedy Channel 999999999999 Comedy Channel+2* * 9 99 Country Music Channel 999999 Crime & Investigation Network* * 9999999 Discovery Channel 9999 9999999 Discovery Home and Health* * 999 Discovery Science* * 999 Discovery Travel & Adventure* * 9999999 Disney Channel 999999999999 E!* * 9 999 ESPN 999999999999 Eurosportnews EXPO Fashion TV FOX8 999999999999 FOX8+2 9 99 * Subscription TV data is only available on an aggregate market level. Page 1 © All Rights Reserved 2009 Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout Those channels whose viewing data is not shown below as being available are included in the channel group ‘Other STV’ From 28 From 11 -

News Corporation 1 News Corporation

News Corporation 1 News Corporation News Corporation Type Public [1] [2] [3] [4] Traded as ASX: NWS ASX: NWSLV NASDAQ: NWS NASDAQ: NWSA Industry Media conglomerate [5] [6] Founded Adelaide, Australia (1979) Founder(s) Rupert Murdoch Headquarters 1211 Avenue of the Americas New York City, New York 10036 U.S Area served Worldwide Key people Rupert Murdoch (Chairman & CEO) Chase Carey (President & COO) Products Films, Television, Cable Programming, Satellite Television, Magazines, Newspapers, Books, Sporting Events, Websites [7] Revenue US$ 32.778 billion (2010) [7] Operating income US$ 3.703 billion (2010) [7] Net income US$ 2.539 billion (2010) [7] Total assets US$ 54.384 billion (2010) [7] Total equity US$ 25.113 billion (2010) [8] Employees 51,000 (2010) Subsidiaries List of acquisitions [9] Website www.newscorp.com News Corporation 2 News Corporation (NASDAQ: NWS [3], NASDAQ: NWSA [4], ASX: NWS [1], ASX: NWSLV [2]), often abbreviated to News Corp., is the world's third-largest media conglomerate (behind The Walt Disney Company and Time Warner) as of 2008, and the world's third largest in entertainment as of 2009.[10] [11] [12] [13] The company's Chairman & Chief Executive Officer is Rupert Murdoch. News Corporation is a publicly traded company listed on the NASDAQ, with secondary listings on the Australian Securities Exchange. Formerly incorporated in South Australia, the company was re-incorporated under Delaware General Corporation Law after a majority of shareholders approved the move on November 12, 2004. At present, News Corporation is headquartered at 1211 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Ave.), in New York City, in the newer 1960s-1970s corridor of the Rockefeller Center complex. -

Supplementary Budget Estimates 2011-12

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Supplementary Budget Estimates 17-20 October 2011 Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Department/Agency: arts portfolio agencies Outcome/Program: various Topic: Media Subscriptions Senator: Senator Ryan Question reference number: 145A Type of Question: Written Date set by the committee for the return of answer: 2 December 2011 Number of pages: 7 Question: 1. Does your department or agencies within your portfolio subscribe to pay TV (for example Foxtel)? ? If yes, please provide the reason why, the cost and what channels. ? What was the cost for 2010-11? ? What is the estimated cost for 2011-12? 2. Does your department or agencies within your portfolio subscribe to newspapers? ? If yes, please provide the reason why, the cost and what newspapers. ? What was the cost for 2010-11? ? What is the estimated cost for 2011-12? 3. Does your department or agencies within your portfolio subscribe to magazines? ? If yes, please provide the reason why, the cost and what magazines. ? What was the cost for 2010-11? ? What is the estimated cost for 2011-12? Answer: The Australia Council 1. No 2. Yes. In order to keep abreast of current issues that directly and indirectly impact on the arts and culture sector, the Australia Council subscribes to the following newspapers: the Sydney Morning Herald, The Australian, The Age, The Daily Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Supplementary Budget Estimates 17-20 October 2011 Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Telegraph, and the Australian Financial Review and the Australia Financial Review Online. -

Convergence 2011: Australian Content State of Play

Screen Australia AUSTRALIAN CONTENT STATE OF PLAY informing debate AUGUST 2011 CONVERGENCE 2011: AUSTRALIAN CONTENT STATE OF PLAY © Screen Australia 2011 ISBN 978-1-920998-15-8 This report draws from a number of sources. Screen Australia has undertaken all reasonable measures to ensure its accuracy and therefore cannot accept responsibility for inaccuracies and omissions. First released 25 August 2011; this edition 26 August 2011 www.screenaustralia.gov.au/research Screen Australia – August 2011 2 CONVERGENCE 2011: AUSTRALIAN CONTENT STATE OF PLAY CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Executive summary ............................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Mapping the media environment ................................................................................ 11 2 CREATING AUSTRALIAN CONTENT ................................................................... 20 2.1 The economics of screen content production ...................................................... 20 2.2 How Australian narrative content gets made ....................................................... 27 2.3 Value to the economy of narrative content production .................................... 39 3 DELIVERING AUSTRALIAN CONTENT .............................................................. 41 3.1 Commercial free-to-air television ............................................................................. -

Achieving 'Growth Within'

A €320-BILLION CIRCULAR ACHIEVING ECONOMY INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY AVAILABLE ‘GROWTH TO EUROPE UP TO 2025 WITHIN’ ACHIEVING ‘GROWTH WITHIN’ | 3 CONTENTS 02 FOREWORD 03 IN SUPPORT OF THE REPORT 06 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 08 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 16 MAIN FINDINGS 54 10 INVESTMENT THEMES 135 APPENDIX – ANALYTICAL METHODOLOGY 139 REFERENCES 4 | ACHIEVING ‘GROWTH WITHIN’ FOREWORD The shift from a linear to circular economy in Europe is accelerating by the transitional power of new technology and business models. As the previous report “Growth Within” (2015) pointed out the value chains mobility, building and food- representing 60 percent of the average EU household budget and 80 percent of resource consumption - could contribute significantly to Europe’s overall economic performance and welfare by adapting a restorative and regenerative economic system. Circular mobility, building environment and circular food systems offer ground-breaking, attractive innovation and investment opportunities, and the EU is uniquely placed to exploit these. This comes at a time when the EU is in great need of industrial renewal and attractive investment opportunities. Circular economic investments offer resilience and transformation of those assets that otherwise might face being stranded or becoming redundant. However, circular economy investment opportunities have remained unrealized until now. I am therefore very pleased with the A European transition would also have insights that this report “Achieving impact far beyond its borders: it could Growth Within” gives in ten attractive create de facto global standards for circular innovation and investment product design and material choices, themes , totaling €320 billion through and provide other world regions with a to 2025: much-needed blueprint. -

Aucun Titre De Diapositive

Channels available programme by programme, territory by territory, via Eurodata TV Worldwide. * Channels measured only on a minute by minute basis are available on an ad-hoc basis “Standard countries” : data available in house, catalogue tariffs are applied “Non-standard countries” : Ad hoc tariffs are applied “Special countries” : special rate card applies “Standard countries” : Eurodata TV’s tariffs are applied, “Non-standard10/05/2006 countries” : Ad hoc tariffs are applied “Special countries” : Fixed and separated prices apply data available in Paris except for channels in blue 14/02/2006 issue This document is subject to change Channels available programme by programme in EUROPE AUSTRIA BELGIUM BOSNIA HERZEGOVINA BULGARIA CROATIA ORF1 ZDF NORTH SOUTH BHT 1 TV TK ALEXANDRA TV GTV HTV 1 ORF2 ATV+ EEN (ex TV1) LA 1 FTV TV TUZLA BBT FoxLife HTV 2 3SAT KANAAL 2 LA 2 HTV OSCAR C BTV NOVA TV ARD Channels available on KETNET/CANVAS RTL - TVI NTV HAYAT BNT/Channel 1 RTL KABEL 1 ad-hoc NICKELODEON CLUB RTL OBN DIEMA 2 PRO7 ARTE SPORZA AB 3 Pink BiH DIEMA + RTL DSF VIJFTV AB 4 RTRS NOVA TV RTL II EUROSPORT VITAYA PLUG TV RTV MOSTAR MM SAT 1 GOTV VT4 BE 1 (ex CANAL+) RTV TRAVNIK MSAT SUPER RTL Puls TV VTM TV BN Evropa TV VOX TW1 Planeta TV TELETEST / FESSEL - GFK/ORF CIM - AUDIMETRIE MARECO INDEX BOSNIA TNS TV PLAN AGB NMR CYPRUS CZECH REP DENMARK ESTONIA FINLAND FRANCE GERMANY ANT 1 CT 1 3+ EESTI TV (ETV) YLE 1 TF1 ARD ARTE SUPER RTL O LOGOS CT 2 ANIMAL PLANET KANAL 2 YLE 2 FRANCE 2 ZDF 3SAT NTV RIK 1 TV NOVA DISCOVERY PBK MTV FRANCE 3 HESSEN -

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout Channel From 28 Dec From 11 July From 27 Feb From 19 From 28 Aug From 26 Nov From 27 May From 26 Aug From 25 Nov From 24 Feb From 1 June From 31 May From 30 Aug From 29 Nov From 28 Feb From 30 May From 29 Aug From 28 Nov From 9 Jan From 29 May From 28 From 12 From 26 From 6 Jan From 24 Feb From 1 Sept From 1 Dec From 29 From 23 From 6 Apr From 2 From 1 Mar From 31 From 29 From 28 From 26 From 28 From 2 Oct From 26 From 27 From 15 From 4 Mar From 8 Apr From 27 From 26 '03 '04 '05 June '05 '05 '06 '07 '07 '07 '08 '08 '09 '09 '09 '10 '10 '10 '10 '11 '11 Aug '11 Feb '12 Aug '12 '13 '13 '13 '13 Dec '13 Feb '14 '14 Nov '14 '15 May '15 Nov '15 Feb '16 Jun '16 Aug '16 '16 Feb '17 Aug '17 Oct '17 '18 '18 May '18 Aug '18 111*** 111 +2*** 13th STREET 13th STREET +2 A&E*** A&E =2*** (5 Oct 16) Adults Only 1 Adults Only 2 Al Jazeera Animal Planet Antenna Arena Arena+2 A-PAC ART Aurora Australian Christian Channel BBC Knowledge BBC WORLD NEWS beIN Sports (Setanta Sports) Binge* (5 Oct 2016) Bio*** Bloomberg Boomerang Box Sets Cartoon Network -

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout Channel From 28 Dec From 11 July From 27 Feb From 19 From 28 Aug From 26 Nov From 27 May From 26 Aug From 25 Nov From 24 Feb From 1 June From 31 May From 30 Aug From 29 Nov From 28 Feb From 30 May From 29 Aug From 28 Nov From 9 Jan From 29 May From 28 From 12 Feb From 26 From 6 Jan From 24 Feb From 1 Sept From 1 Dec From 29 From 23 From 6 Apr From 2 Nov From 1 Mar From 31 From 29 From 28 From 26 From 28 From 2 Oct From 26 From 27 From 15 From 4 Mar From 8 Apr From 27 From 26 From 24 From 3 Nov From 29 '03 '04 '05 June '05 '05 '06 '07 '07 '07 '08 '08 '09 '09 '09 '10 '10 '10 '10 '11 '11 Aug '11 '12 Aug '12 '13 '13 '13 '13 Dec '13 Feb '14 '14 '14 '15 May '15 Nov '15 Feb '16 Jun '16 Aug '16 '16 Feb '17 Aug '17 Oct '17 '18 '18 May '18 Aug '18 Feb '19 '19 Dec '19 111 *** (ceased 6 Nov 19) 111 +2*** (ceased 6 Nov 19) 13th STREET (ceased 29 Dec 19) 13th STREET +2 (ceased 29 Dec 19) A&E*** A&E =2*** (5 Oct 16) Adults Only 1 Adults Only 2 Al Jazeera Animal Planet Antenna Arena Arena+2 A-PAC ART Aurora Australian Christian Channel BBC Knowledge BBC WORLD NEWS beIN Sports (Setanta Sports) Binge* (ceased 6 Nov 19) Bio*** -

110125 Fox Sports to Screen Triple M Legends of Origin Match Live

Media Release 252525 January 2012011111 FOX SPORTS TO SCREEN ‘‘‘TRIPLE‘TRIPLE M LEGENDS OF ORIGINORIGIN’’’’ MATCH LIVE FOX SPORTS today announced that it will broadcast Sydney’s TRIPLE M LEGENDS OF ORIGINORIGIN match from Parramatta Stadium LIVE this Thursday, January 27 at 7.7.00000pm0pm AEDST on FOX SPORTS 1HD and FOX SPORTS 1. Featuring an all-star line-up of Australian sporting heroes, more than 20,000 tickets have been sold to the match to raise money for the Premier’s Flood Relief fund. The Queensland and New South Wales sides will battle it out for the Jordan Rice Shield. The unique co-production between FOX SPORTS and Triple M will screen LIVE on FOX SPORTS 1HD and FOX SPORTS 1 from 7.00pm, with HG Nelson (Greig Pickhaver), Andrew JohnsJohns, Greg Martin and Dan Ginnane calling all the action which will be simulcast on Triple M live on 104.9FM in Sydney and 104.5 FM in Brisbane plus on digital radio station Barry.com.au . Australia’s leading general sports website www.foxsports.com.au and www.triplem.com.au will also feature live streams of the broadcast. A score of the greatest names in State of Origin history (full line-up below) will be involved in the match that will be played in four 15 minute quarters, with the Queensland side coached by Wally Lewis and Phil Gould at the helm of New South Wales. Lewis, Gould and match referee Bill Harrigan will be miked up throughout the match. The match will also see FOX SPORTS commentators go head-to-head, with New South Wales legends Greg Alexander and Brett Kimmorley as well as Queensland heroes Gary Belcher and Gorden Tallis among those strapping on the boots. -

95 Subscription TV Channels

Channel Start Date End Date 111 30th Nov 2008 111 +2 29th Nov 2009 13th Street 29th Nov 2009 16th Dec 2019 13th Street +2 28th Nov 2010 16th Dec 2019 A&E 12th Feb 2012 A&E +2 2nd Oct 2016 Animal Planet 28th Dec 2003 BBC First 3rd August 2014 BBC Earth 30th Nov 2008 BBC World News 9th Jan 2011 beIN Sports 1 29th Nov 2011 beIN Sports 2 28th Aug 2016 beIN Sports 3 28th Aug 2016 Binge 2nd Oct 2016 6th Nov 2019 Bio 28th May 2016 1st Nov 2015 Boomerang 4th Sept 2005 BoxSets 3rd Nov 2014 Cartoon Network 3rd August 2003 Cbeebies 30th Nov 2008 CMT 1st July 2020 Channel [V] 3rd Aug 2003 Club MTV 27th Feb 2005 CNBC 3rd Aug 2003 28th Dec 2014 Comedy Channel 3rd Aug 2003 31st Aug 2020 Comedy Channel +2 19th June 2005 6th Nov 2019 Country Music Channel 28th Aug 2016 30th June 2020 crime + investigation 1st Jan 2006 Discovery Channel 3rd Aug 2003 Discovery Channel +2 29th Nov 2009 Discovery Home & Health 1st Jan 2006 3rd Aug 2014 Discovery Kids 3rd Nov 2014 31st Jan 2020 Discovery Turbo 29th Nov 2009 Discovery Turbo +2 29th Nov 2009 Disney Channel 3rd Aug 2003 29th Feb 2020 Disney Junior 26th Feb 2006 29th Feb 2020 DreamWorks 1st July 2021 E! 19th June 2005 E! +2 23rd Feb 2020 ESPN 28th Dec 2003 ESPN2 27th Nov 2011 Eurosport 28th June 2015 31st Jan 2020 FMC - Family Movie Channel 29th Nov 2009 26th Aug 2012 FOX Arena 3rd Aug 2003 FOX Arena +2 19th June 2005 FOX Classics 3rd Aug 2003 FOX Classics +2 19th June 2005 FOX COMEDY 3rd Nov 2019 FOX COMEDY +2 3rd Nov 2019 FOX CRICKET 26th Aug 2018 FOX CRIME 3rd Nov 2019 FOX CRIME +2 3rd Nov 2019 Channel Start -

Edgar Cayce on Channeling Your Higher Self by Henry Reed

Edgar Cayce on Channeling Your Higher Self by Henry Reed Online Spiritual Book Club Chapter Summaries by Julie Geigle, MA Edu. www.heavensenthealing.us Edgar Cayce on Channeling Your Higher Self Table of Contents Ch 1 What is Channeling? Ch 2 Listen to Your Intuition: The Channel of Your Guardian Angel Ch 3 Dreams: The Nightly Channel of the Higher Self Ch 4 The Creative Channel of the Mind: What We Think, We Become Ch 5 Meditation: Channel of the Spirit Ch 6 Inspirational Writing Ch 7 Artistic Channels of Creativity Ch 8 The Visionary Channel of Your Imagination Ch 9 Who's There? Identifying the Spirit Who Speaks Ch 10 Evaluating Channeled Guidance Ch 11 Using Hypnosis to Become a Trance Channel Ch 12 The Channel of Cooperation in a Group Ch 13 Being a Channel of Healing Forces Ch 14 Being Yourself: The Ultimate Form of Channeling Chapter 1: What is Channeling Today's Affirmation: Every day my inner voice becomes louder and clearer. "Learning that you, too, are a channel of spirit can be a means of spiritual awakening. The highest psychic realization, Cayce declared, is that God talks directly to human beings." ~Edgar Cayce What is Channeling? • In its most general sense it's a means of transmission • The channel receives and passes along information • Inspiration & creativity are aspects of channeling • Being able to elevate others to higher states of consciousness & bring out the best in people • Edgar Cayce's work is known as "classic channeled metaphysical literature" • We are all channels of Divine energy • It is transmitting something which is beyond one's personal self • A channel may be asleep, in a meditation, in a trance or awake while channeling • There are as many ways to channel as their are individuals that channel • A channeler brings forth information that's not part of the channeler's own learning or experience "Every day, in countless ways, you and I are channels of spirit, of ideas, and of resources that come from beyond our conscious personalities . -

The Case Against Vcrs That Zap Commercials, 43 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 43 | Issue 2 Article 4 1-1992 I Can't Believe I Taped the Whole Thing: The aC se against VCRs That Zap Commercials Steven S. Lubliner Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven S. Lubliner, I Can't Believe I Taped the Whole Thing: The Case against VCRs That Zap Commercials, 43 Hastings L.J. 473 (1992). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol43/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Can't Believe I Taped the Whole Thing: The Case Against VCRs That Zap Commercials by Steven S. Lubliner* Any attempt to make the radio an advertising medium, m the accepted sense of the term, would, we think, prove positively offensive to great numbers of people. The family circle is not a public place, and adver- tising has no business intruding there unless it is invited.' Control over one's environment is a precious commodity On any given day the average person must obey superiors, pay others for goods and services, tend to the needs of children, and-the unkindest cut of all-submit to the demands and inexorable decline of the body. When, however, all seems lost it is comforting to know that one last vestige of control remains firmly within an individual's grasp--the pause and fast * Member, Third Year Class; B.A.