Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malta and Gozo - Experiences of a Study Tour from 14Th to 21St September 2019 Text and Photos: Hans-Rudolf Neumann

Malta and Gozo - Experiences of a study tour from 14th to 21st September 2019 Text and Photos: Hans-Rudolf Neumann Saturday, 14th September 2019 The morning flight from Berlin via Frankfurt Main to Malta with Lufthansa ran without any incidents. But check-in service in Berlin leaves a lot to be desired; the transition to digital full automation to reduce staff provoked the oppo- site effect. Luggage check-in and boarding on two different ends of the airport caused anno- yance, while during boarding two flights were serviced on the same counter. One two Warsaw and one to Frankfurt Main – the line on luggage security was more than 200 people and it was safe to ask the pilot again if this is the right plane when entering the plane. The on-board meal on the flight to Frankfurt consisted of a 30 g al- mond tartlet of a 65 mm size and a drink, on the connecting flight to Malta we had a honey nut bar and another drink. Regarding that you had to leave the house at 4.45 am and entered the hotel in Malta around 12.40 pm, it was a re- Fig. 01: First group photo on the first day of the ex- markable performance, particularly as there was cursion: an INTERFEST study group with their no time to buy additional food in Frankfurt due wives and guests at the foot of the St. Michael bas- to the short connection time. There were better tion of the landfront in La Valletta under the um- times! Anyways, the dinner together at Hotel brella of the European cultural route FORTE CUL- Bay View in Sliema offered a rich buffet inclu- TURA®. -

Building the Temple of Salomo in the Early Medieval „Alamannia“

Journal of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JLAH) Issue: Vol. 1; No. 4; April 2020 pp. 163-185 ISSN 2690-070X (Print) 2690-0718 (Online) Website: www.jlahnet.com E-mail: [email protected] Building the Temple of Salomo in the Early Medieval „Alamannia“ Dr. Thomas Kuentzel M.A. Untere Masch Strasse 16 Germany, 37073 Goettingen E-mail: [email protected] The diocese of Constance is one of the largest north of the Alps, reaching from the Lakes of Thun and Brienz down to Stuttgart and Ulm, from the river Iller (passing Kempten) to the Rhine near Lörrach and Freiburg. Its origins date back to the end of the 6th century; when saint Gall came to the duke of Alamannia, Gunzo, around the year 613, the duke promised him the episcopate, if he would cure his doughter.i In the 9th century some of the bishops also were abbots of the monasteries on the Island Reichenau and of Saint Gall. Three of the bishops were called Salomon, one being the uncle of the following.ii The noble family they belonged to is not known, but they possessed land on the southern shore of Lake Constance, in the province of Thurgau. Salomon III. was educated in the monastery of Saint Gall, and prepared especially for the episcopate. Maybe his uncle and granduncle also benefitted from such an education. Even their predecessor, bishop Wolfleoz, started his career as monk in Saint Gall. It is likely that the three Salomons were given their names with the wish, that they once would gain this office. -

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

HANDBOOK for Visiting Scholars

INTERNATIONAL OFFICE HANDBOOK for Visiting Scholars » www.leuphana.de/io 2 HANDBOOK FÜR GASTWISSENSCHAFTLER // KAPITELNAME WELCOME Welcome at Leuphana University of Lüneburg – one of Germany’s young and progressive universities. We are delighted to welcoming you on our campus, working with you, learning from you, and discussing ideas with you. An intellectually stimulating atmosphere and a place to work and to live awaits you. We hope that this handbook will be useful for your fi rst orientation at the University and in the city of Lüneburg. Furthermore, the International Offi ce team will assist you during the initial phase, and, of course, will give advice and support throughout your stay in Lüneburg. The International Offi ce generally promotes and coordinates the international cooperation and exchange programs. Thus, it is the central point of contact for all international visitors. The International Offi ce mainly takes care of organisational questions that are related to your stay, while the core academic issues are taken care of by your host professor or the department. We will make every effort to ensure that your stay in Lüneburg will be a pleasant and successful one and that you feel at home. Your International Offi ce Team 4 HANDBOOK FÜR GASTWISSENSCHAFTLER // INHALT HANDBOOK FÜR GASTWISSENSCHAFTLER // INHALT 5 IN BRIEF: UNIVERSITY, TOWN, STATE, 20 Opening a bank account 39 Language Centre 51 Bicycle Rental 68 Literature Club 81 Punctuality COUNTRY 21 Further information 40 Campus Facilities 51 Driving by car 68 Museums 81 Invitations -

History of the Royal Marines 1837-1914 HE Blumberg

History of the Royal Marines 1837-1914 HE Blumberg (Minor editing by Alastair Donald) In preparing this Record I have consulted, wherever possible, the original reports, Battalion War and other Diaries, accounts in Globe and Laurel, etc. The War Office Official Accounts, where extant, the London Gazettes, and Orders in Council have been taken as the basis of events recounted, and I have made free use of the standard histories, eg History of the British Army (Fortescue), History of the Navy (Laird Clowes), Britain's Sea Soldiers (Field), etc. Also the Lives of Admirals and Generals bearing on the campaigns. The authorities consulted have been quoted for each campaign, in order that those desirous of making a fuller study can do so. I have made no pretence of writing a history or making comments, but I have tried to place on record all facts which can show the development of the Corps through the Nineteenth and early part of the Twentieth Centuries. H E BLUMBERG Devonport January, 1934 1 P A R T I 1837 – 1839 The Long Peace On 20 June, 1837, Her Majesty Queen Victoria ascended the Throne and commenced the long reign which was to bring such glory and honour to England, but the year found the fortunes of the Corps at a very low ebb. The numbers voted were 9007, but the RM Artillery had officially ceased to exist - a School of Laboratory and nominally two companies quartered at Fort Cumberland as part of the Portsmouth Division only being maintained. The Portsmouth Division were still in the old inadequate Clarence Barracks in the High Street; Plymouth and Chatham were in their present barracks, which had not then been enlarged to their present size, and Woolwich were in the western part of the Royal Artillery Barracks. -

Building of the Berlin Wall

BUILDING OF THE BERLIN WALL a A CITY TORN APART b A CITY TORN APART OF BUILDING THE BERLIN WALL in conjunction with a symposium given on 27 OCTOBER 2011 at the NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, DC WASHINGTON, DC RECORDS ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND at the 27 OCTOBER 2011 in conjunction with a symposium given on BUILDING BERLIN WALL OF ITY TORN APART A C BUILDING OF THE BERLIN WALL brandenburg gate Built in 1791, standing 85 feet high, 215 feet long and 36 feet wide, this former city gate is one of the most iconic symbols of Berlin and Germany. Throughout its existence it has served as a visual representation of various political ideologies, ranging from Prussia’s imperialism to East Germany’s communism. It was closed by the East Germans on 14 August 1961 in a response to West Berliners’ demonstration against the building of the wall dividing their city into East and West. It remained closed until 22 December 1989. Its design is based upon the gate way to the Propylaea, the entry into the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. It has 12 Doric columns, six to a side, forming five passageways. The central archway is crowned by the Quadriga, a statue consisting of a four horse chariot driven by Victoria, the Roman goddess of victory. After Napoleon’s defeat, the Quadriga was returned to Berlin and the wreath of oak leaves on Victoria was replaced with the new symbol of Prussia, the Iron Cross. i A CITYC ITY TORNTO RN APART a family divided A couple from Berlin may never see each other again because they became separated by the newly formed Berlin Wall. -

Fyrish Monument and Family

Sir Hector’s Follies It is normally stated that the Fyrish Monument was built by General Sir Hector Munro of Novar (1727 – 1806) in the 1780s on the proceeds of his prize monies and pensions from his various Indian campaigns. The tradition runs that this was an early work creation scheme for local people who were suffering the effects of food shortage and unemployment. (There is the rather tall story that he personally rolled stones down from the summit overnight to create additional employment!) And it is said to be based on the gates of the coastal fortress of ‘Nepapatuam’, which he captured in 1781from the Dutch and their Indian allies. The Highland Archives have Novar Estate papers which refer to construction in 1792. (See Evanton Oral History website). The monument, a Listed Building (category B) from 1971, was originally painted white according to one early source (although this may be because it so appears when the sun shines on it). Strangely the outlying pillars at each end are several metres out of alignment with the main monument. 2 smaller monuments, with straight sides, sit on Meann Cnoc and Creag Ruadh, which are now clearly visible from the road (pictures). Monument on Creag Ruadh Monument on Meann Chnoc (‘Little Fyrish’) The poet Robert Southey, touring the Highlands in 1819, in conjunction with Thomas Telford, wrote of “some odd edifices on the summits which he (Sir Hector) is said to have designed as imitations of the hillforts in India.” An Indian hillfort is very different from a city gate. There is no evidence of any special gates for Negapatuam itself, and the fortress was of distinctly European design. -

3D Modelling of a 15Th Century City Gate of Rennes: Portes Mordelaises Jean-Baptiste Barreau, Elen Esnault, Jérôme Foucher, Manon Six, Cécile Le Faou

3D modelling of a 15th century city gate of Rennes: Portes Mordelaises Jean-Baptiste Barreau, Elen Esnault, Jérôme Foucher, Manon Six, Cécile Le Faou To cite this version: Jean-Baptiste Barreau, Elen Esnault, Jérôme Foucher, Manon Six, Cécile Le Faou. 3D modelling of a 15th century city gate of Rennes: Portes Mordelaises. Virtual Archaeology Review, Spanish Society of Virtual Archaeology, 2020, 11 (22), pp.41. 10.4995/var.2020.12653. hal-02459091 HAL Id: hal-02459091 https://hal-univ-rennes1.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02459091 Submitted on 29 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Virtual Archaeology Review, 11(22): 41-55, 2020 https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2020.12653 © UPV, SEAV, 2015 Received: November 2, 2019 Accepted: January 8, 2020 3D MODELLING OF A 15TH CENTURY CITY GATE OF RENNES: PORTES MORDELAISES MODELADO EN 3D DE UNA PUERTA DE LA CIUDAD DE RENNES DEL SIGLO XV: PORTES MORDELAISES Jean-Baptiste Barreaua,* , Elen Esnaultb, Jérôme Foucherc , Manon Sixd , Cécile Le Faoud a Univ Rennes-CNRS-CReAAH UMR 6566, Campus de Beaulieu Bât24 RDC P009 Avenue du Général Leclerc, Rennes, 35000, France. -

Hazor, Dor and Megiddo in the Time of Ahab and Under Assyrian Rule Author(S): EPHRAIM STERN Source: Israel Exploration Journal, Vol

Hazor, Dor and Megiddo in the Time of Ahab and under Assyrian Rule Author(s): EPHRAIM STERN Source: Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 40, No. 1 (1990), pp. 12-30 Published by: Israel Exploration Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27926166 Accessed: 20-10-2017 06:56 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Israel Exploration Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Israel Exploration Journal This content downloaded from 109.67.249.19 on Fri, 20 Oct 2017 06:56:20 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Hazor, Dor and Megiddo in the Time of Ahab and under Assyrian Rule* EPHRAIM STERN Institute of Archaeology The Hebrew University of Jerusalem INTRODUCTION IN the early 1960s, shortly after the publication of his well-known article, 'Hazor, Gezer and Megiddo in Solomon's Time',1 the late Y. Yadin advised me to undertake an examination of the fortifications and gates of Palestine as the subject of my master's thesis. After completing it, I published some of my conclusions on the Iron Age gates,2 to which I now return after excavating two gates at Dor. -

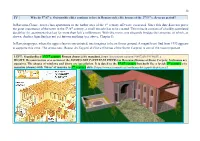

IV in Ravenna-Classe, Lower-Class Apartments in the Harbor Area of The

38 IV Why do 5th/6th c. Ostrogothic elites continue to live in Roman-style elite houses of the 2nd/3rd c. Severan period? In Ravenna-Classe, lower-class apartments in the harbor area of the 1st century AD were excavated. Since this date does not prove the great importance of the town in the 5th/6th century, a small miracle has to be created. This miracle consists of a boldly postulated durability for apartments that last for more than half a millennium. With this move, one elegantly bridges the centuries, of which, as shown, Andrea Agnellus has not yet known anything (see above, Chapter I). In Ravenna proper, where the upper class is concentrated, one imagines to be on firmer ground. A magnificent find from 1993 appears to supports this view. The aristocratic Domus dei Tappeti di Pietra (Domus of the Stone Carpets) is one of the most important LEFT: Standardized 1st/2nd century Roman domus (city mansion). [https://pl.pinterest.com/pin/91057223699970657/.] RIGHT: Reconstruction of a section of the DOMUS DEI TAPPETI DI PIETRA in Ravenna (Domus of Stone Carpets; bedrooms are upstairs). The shapes of windows and doors are speculation. It is dated to the 5th/6th century but built like a lavish 2nd century city mansion (domus) with 700 m2 of mosaics in 2nd century style. [https://www.ravennantica.it/en/domus-dei-tappeti-di-pietra-ra/.] 39 Italian archaeological sites discovered in recent decades. Located inside the eighteenth-century Church of Santa Eufemia, in a vast underground environment located about 3 meters below street level, it consists of 14 rooms paved with polychrome mosaics and marble belonging to a private building of the fifth-sixth century. -

Download IDT V4 in PDF Format

This page intentionally left blank. INFRASTRUCTURE DATA TAXONOMY OVERVIEW About the Infrastructure Data Taxonomy (IDT) Infrastructure and its elements can be described and categorized in various ways. Industries operating in various sectors of the Nation’s infrastructure, for example, often use the same term to refer to very different things. Terminology also lacks consistency among government agencies at the Federal, State, and local levels. Toward that end, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Infrastructure Protection created the Infrastructure Data Taxonomy (IDT). The IDT is a nomenclature that can be used by the infrastructure protection community and industry partners to categorize infrastructure assets and establish a common language for all to use. It establishes a detailed and structured terminology that facilitates data discovery, management, and enables data sharing among mission partners and systems. Using the IDT The IDT Table of Contents serves as a quick reference for the taxonomy in which infrastructure sector assets can be categorized. The taxonomy is organized around the 18 sectors recognized by DHS: Agriculture and Food, Banking and Finance, Chemical, Defense Industrial Base, Energy, Emergency Services, Information Technology, Communications, Postal and Shipping, Healthcare and Public Health, Transportation, Water, National Monuments & Icons, Commercial Facilities, Government Facilities, Dams, Nuclear, and Critical Manufacturing. Within each sector an IDT Path can be assigned with up to five levels. The first level is determined by one of the 18 infrastructure categories. The other levels are used when additional descriptive information is available to describe an infrastructure element. The five levels of differentiation found within the IDT are the sector, sub-sector, segment, sub-segment, and asset level. -

3D Modelling of a 15Th Century City Gate of Rennes

Virtual Archaeology Review, 11(22): 41-55, 2020 https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2020.12653 © UPV, SEAV, 2015 Received: November 2, 2019 Accepted: January 8, 2020 3D MODELLING OF A 15TH CENTURY CITY GATE OF RENNES: PORTES MORDELAISES MODELADO EN 3D DE UNA PUERTA DE LA CIUDAD DE RENNES DEL SIGLO XV: PORTES MORDELAISES Jean-Baptiste Barreaua,* , Elen Esnaultb, Jérôme Foucherc , Manon Sixd , Cécile Le Faoud a Univ Rennes-CNRS-CReAAH UMR 6566, Campus de Beaulieu Bât24 RDC P009 Avenue du Général Leclerc, Rennes, 35000, France. [email protected] b Inrap-CReAAH UMR 6566, 37 Rue du Bignon Cs 67737 Cesson-Sévigné, 35577, France. [email protected] c Société Polymorph Software, 22 Rue Jean Marie David, Pacé, 35740, France. [email protected] a Musée de Bretagne, 10 Cours des Alliés, Rennes, 35000, France. [email protected]; [email protected] Highlights: The Portes Mordelaises, a 15th century defensive gate and associated structures, one of the principal historical sites situated in Rennes, France, has been entirely virtually reconstructed in 3D. An original methodology was adopted in order to reconstruct the 3D model of this unique architectural edifice over the course of its six-year excavation. Recognised as being of great national interest, a virtual reality installation was created in an exhibition presenting its reconstruction, garnering more than 45000 visitors. Abstract: The Portes Mordelaises, remnants of the medieval city walls of Rennes, France, has been the subject of several archaeological excavations until 2017. From these excavations, we created a three-dimensional (3D) model of the site reconstructed as it would have appeared during the 15th century, including the surrounding plus the interiors of its famed towers.