Understanding Urban Reserves: Special Reference to Kapyong Gregory Mason University of Manitoba January 24, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lands Envrironment Action Fund Toolkit

Lands Environmental Action Fund (LEAF) Manitoba First Nations ENVIRONMENT ECONOMY EMPLOYMENT 2014 CREATING OPPORTUNITIES Creating Environmental Economic Opportunities 2014 Produced by: David Lane, DMCL Environmental Anupam Sharma, Director of Operations, DOTC Robert Daniels, CEO, DOTC This project would not have been possible without generous support and guidance from the Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council, the members of the DOTC Council of Chiefs, and key individuals in their respective communities (Birdtail Sioux First Nation, Dakota Tipi First Nation, Long Plain First Nation, Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation, Sandy Bay Ojibway First Nation, Swan Lake First Nation, and Waywaysecappo First Nation). The information contained within this toolkit is collected from and considered to be part of the public domain. Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council offers this guide without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied. Nor does Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council assume any liability for any damages arising from the use of this product. Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council Head Office Long Plain Reserve #6, Band #287 Room 230, 2nd Floor 5010 Crescent Road West Portage la Prairie, MB Mailing Address: P.O. Box 338 Portage la Prairie, MB R1N 3B7 Website: www.dotc.mb.ca Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, through the Lands Environmental Action Fund (LEAF), provided funding for this project. March 2014 Lands Environmental Action Fund (LEAF) 2 Creating Environmental Economic Opportunities 2014 CONTENTS: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... -

Assembly of First Nations Mitigating Climate Change

Assembly of First Nations Mitigating Climate Change Community Success in Developing Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Projects Assembly of First Nations Table of Contents Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... 3 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 4 Hupacasath First Nation Micro-hydro Plant..................................................................... 6 Taku River Tlingit Power Station..................................................................................... 8 Nacho Nyak Dun Government House ............................................................................ 10 Xeni Gwet'in First Nation Solar Power Project.............................................................. 11 Rolling River Health Centre CBIP Project..................................................................... 14 Rolling River First Nation Wind-Monitoring Project..................................................... 15 Skownan Home Energy Efficiency Workshop Project................................................... 16 Swan Lake Community Energy Baseline Project........................................................... 17 Swan Lake First Nation Wind-Monitoring Project......................................................... 18 Chakastapaysin and Peter Chapman First Nations Independent Power Production....... 19 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Hydro Project............................................................... -

Since 1985, Stars Has Flown More Than 45,000 Missions Across Western Canada

2019/20 Missions SINCE 1985, STARS HAS FLOWN MORE THAN 45,000 MISSIONS ACROSS WESTERN CANADA. Below are 760 STARS missions carried out during 2019/20 from our base in Winnipeg. MANITOBA 760 Alonsa 2 Altona 14 Amaranth 2 Anola 2 Arborg 4 Ashern 15 Austin 2 Bacon Ridge 2 Balsam Harbour 1 Beausejour 14 Benito 1 Beulah 1 Birds Hill 2 Black River First Nation 2 Bloodvein First Nation 6 Blumenort 1 Boissevain 3 Bowsman 1 Brandon 16 Brereton Lake 3 Brokenhead Ojibway Nation 1 Brunkild 2 Caddy Lake 1 Carberry 1 Carman 4 Cartwright 1 Clandeboye 1 Cracknell 1 Crane River 1 Crystal City 6 Dacotah 3 Dakota Plains First Nation 1 Dauphin 23 Dog Creek 4 Douglas 1 Dufresne 2 East Selkirk 1 Ebb and Flow First Nation 2 Edrans 1 Elphinstone 1 Eriksdale 9 Fairford 2 Falcon Lake 1 Fannystelle 1 Fisher Branch 1 Fisher River Cree Nation 4 Fort Alexander 3 Fortier 1 Foxwarren 1 Fraserwood 2 Garson 1 Gilbert Plains 1 Gimli 15 Giroux 1 Gladstone 1 Glenboro 2 Grand Marais 2 Grandview 1 Grosse Isle 1 Grunthal 5 Gypsumville 3 Hadashville 3 Hartney 1 Hazelridge 1 Headingley 5 Hilbre 1 Hodgson 21 Hollow Water First Nation 3 Ile des Chênes 3 Jackhead 1 Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation 1 Kelwood 1 Kenton 1 Killarney 8 Kirkness 1 Kleefeld 1 La Rivière 1 La Salle 1 Lac du Bonnet 3 Landmark 3 Langruth 1 Lenore 1 Libau 1 Little Grand Rapids 3 Little Saskatchewan First Nation 7 Lockport 2 Long Plain First Nation 5 Lorette 3 Lowe Farm 1 Lundar 3 MacGregor 1 Manigotagan 2 Manitou 3 Marchand 2 Mariapolis 1 McCreary 1 Middlebro 5 Milner Ridge 2 Minnedosa 4 Minto 1 Mitchell -

Aboriginal Organizations and with Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth

ABORIGINAL ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People 2011/2013 ABORIGINAL ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Métis People 2011 / 2013 ________________________________________________________________ Compiled and edited by Aboriginal Education Directorate and Aboriginal Friendship Committee Fort Garry United Church Winnipeg, Manitoba Printed by Aboriginal Education Directorate Manitoba Education, Manitoba Advanced Education and Literacy and Aboriginal Affairs Secretariat Manitoba Aboriginal and Northern Affairs INTRODUCTION The directory of Aboriginal organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to assist people to locate the appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Aboriginal organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown considerably since its initial edition, which had 16 pages compared to the 100 pages of the present edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Aboriginal cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present in this directory an accurate and up-to-date listing. Fax numbers, Email addresses and Websites have been included whenever available. Inevitably, errors and omissions will have occurred in the revising and updating of this Directory, and the committee would greatly appreciate receiving information about such oversights, as well as changes and new information to be included in a future revision. Please call, fax or write to the Aboriginal Friendship Committee, Fort Garry United Church, using the information on the next page. -

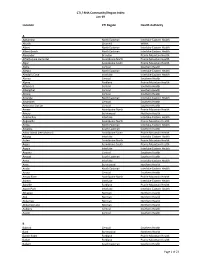

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Page 1 of 3 MANITOBA FIRST NATIONS POLICE SERVICE

MANITOBA FIRST NATIONS POLICE SERVICE (DAKOTA OJIBWAY POLICE SERVICE) History The original establishment of the Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council Police Department, now known as the Dakota Ojibway Police Service, dated December 1974, was prepared and agreed to by all Chiefs of the D.O.T.C. After three years of negotiations, funding was approved by the different levels of government. In November of 1977, the police department commenced operations with one Chief of Police and nine members. The program was funded by Indian & Northern Affairs Canada from 1977 to 1993. The development of the Police Service was to establish local control and accountability to the First Nation communities. In November of 1993, the Police Service ceased operations due to a lack of funding commitment from the Province of Manitoba. Tripartite negotiations reconvened in 1994 and technical meetings took place as follows: March 10, May 12, May 26 and June 23, 1994. On May 19, 1994, the D.O.T.C. Council of Chiefs and representatives from both levels of Government, Manitoba Justice and Public Safety Canada were able to secure an Interim Policing Service Agreement which saw the restoration of joining policing services (D.O.P.S./R.C.M.P.) to (7) seven of the (8) eight D.O.T.C. Member First Nation communities, with the effective start date of June 1, 1994. On December 31, 1994, a long-term Tripartite Agreement was finalized and on February 1, 1995, the Dakota Ojibway Police Service resumed full-time policing services to (6) six D.O.T.C. First Nation communities: Birdtail Sioux First Nation, Dakota Plains Wahpeton Nation, Long Plain First Nation, Canupawakpa Dakota Nation, Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation and Sioux Valley Dakota Nation. -

Comparative Indicators of Population Health and Health Care Use for Manitoba’S Regional Health Authorities

Comparative Indicators of Population Health and Health Care Use for Manitoba’s Regional Health Authorities A POPULIS Project June 1999 Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba Charlyn Black, MD, ScD Noralou P Roos, PhD Randy Fransoo, MSc Patricia Martens, PhD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the many individuals whose efforts and expertise made it possible to produce this report, especially Jan Roberts and Carolyn DeCoster for their consultations and advice throughout the project. We also wish to express our appreciation to the many individuals who provided feedback on draft versions, including John Millar and Fred Toll, and those who provided insights into the data interpretation, including Donna Turner and Bob Tate. Because of the extensive nature of this report, we gratefully acknowledge many persons for their technical support: Shelley Derksen, David Friesen, Pat Nicol, Dawn Traverse, Bogdan Bogdanovic, Charles Burchill, Leonard MacWilliam, Sandra Peterson, Carmen Steinbach, Randy Walld, and Erin Minish. Thanks to Carole Ouelette for final preparation of this document. We are indebted to the Manitoba Cancer Treatment and Research Foundation, Health Information Services (Manitoba Health) and the Office of Vital Statistics in the Agency of Consumer and Corporate Affairs for providing data. The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by Manitoba Health was intended or should be implied. This report was prepared at the request of Manitoba Health as part of the contract between the University of Manitoba and Manitoba Health. Tutorial Readers who would like to proceed directly to the section that describes how one might apply the information found in this document are encouraged to go directly to section 4: Interpreting the Data for Local Use, on page 20. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Manitoba Public Accounts, 1994-95. Vol. 2 Supplementary Information

DDV CA2MA TR P71 public accounts Carleton University Documents Division 1994-95 ocr 18 1995 FOR REFERENCE ONLY volume 2 — supplementary information Manitoba Finance for the year ended March 31, 1995 VOLUME 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION. 3 AUDITOR’S REPORT. 5 SALARIES AND WAGES PAID TO EMPLOYEES. 9 PAYMENTS TO CORPORATIONS, FIRMS, INDIVIDUALS, OTHER GOVERNMENTS AND GOVERNMENT AGENCIES. 93 Carleton Unsvs'siiy j Documents Division \ OCT 18 1995 for reference only STATEMENT OF PAYMENTS IN EXCESS OF $5,000 TO CORPORATIONS, FIRMS, INDIVIDUALS, OTHER GOVERNMENTS AND GOVERNMENT AGENCIES For the fiscal year ended March 31,1995 " ' ■ V PAYMENTS TO CORPORATIONS, ETC 1994-95 93 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ASH MANAGEMENT GROUP INC $7,140; ADAM A R, MORRIS $20,161; JUNIPER EMBLEMS LTD, LACOMBE AB DAUPHIN $22,759; ADVANCE PROFESSIONAL ELECTRONICS $6330; KORTEX COMPUTER CENTRE $55,645; KOVNATS ABE $6,810; ARTHUR ANDERSEN & CO $15,604; ASHTON STEVE $14,085; KOWALSKI GARY $29,169; KWIK KOPY PRINTING $61,781; ASSEMBLEE INTERNATIONALE DES $8,769; LAMOUREUX KEVIN $29,429; LATHLIN OSCAR $49384; PARLEMENTAIRES, PARIS FRANCE $6,340; BAIZLEY DR LAURENDEAU MARCEL $29,401; LEECH PRINTING LTD, OBIE $6341; BANMAN BOB, STEINBACH $20337; BARKMAN BRANDON $5328; LOVATT JAMES, EDMONTON AB $7392; AGNES, STEINBACH $6309; BARRETT BECKY $29,240; LYON STERLING R $29,914; MACKINTOSH GORD $29365; BARROW HAZEL E, CREIGHTON SK $9,526; BILTON MACKLING ALVIN, DUGALD $18325; MALINOWSKI FATHER MILDRED M, OTTAWA ON $11,624; BISON CUSTOMIZED DON, NEWMARKET ON $22588; MALOWAY JIM $27,428; -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

SCO CEC Submission 2007

Submission by the Southern Chiefs’ Organization to the Clean Environment Commission on the Hog Production Industry Review SOUTHERN CHIEFS’ ORGANIZATION HEAD OFFICE • LONG PLAIN FIRST NATION P.O. Box 1147 • Portage La Prairie • Manitoba R1N 3J9 WINNIPEG SUB-OFFICE • 225-530 Century Street • Winnipeg • Manitoba • R3H OY4 Southern Chiefs’ Organization Southern Chiefs’ Organization Aboriginal people have inherent rights and treaty rights. These rights include the right to clean water, as well as the right to protect our waters according to our own laws, teachings and traditions. Water is sacred to Aboriginal people; the source from which all life flows. Our traditions teach about a sacred right to live with water, and a sacred responsibility to protect water. The mandate of the Southern Chiefs’ Organization is to “protect, preserve, promote and enhance First Nations’ peoples’ inherent rights, languages, customs and traditions through the application and implementation of the spirit and intent of the treaty- making process”. With regard to the environment, the Chiefs of southern First Nations: Passed a resolution on environmental research and stewardship (September 2004); Accepted the Environmental Strategy for Southern First Nations (February 2005); Created the First Nations Water Protection Council (March 2005). Through the First Nations Water Protection Council, the Southern Chiefs’ Organization has begun an Indigenous Water Inventory for Source Water Protection within the traditional territories of the 36 southern First Nations of Manitoba. Despite Aboriginal rights to water continually being diminished, we will continue to defend our inherent right to water and to live up to our responsibility of protecting water within our traditional territories. -

FINDING AID Administrative Records of the Conference of Manitoba And

FINDING AID Administrative Records of the Conference of Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario Fonds Series 509/2 Superintendents of Home Missions Excerpt 4: Property Grants and Loans for First Nations Communities Author Linda White, 2002; Revised 2003, 2006, 2013, 2014 United Church of Canada Archives Winnipeg uccarchiveswinnipeg.ca © 2006 UCC Archives Winnipeg Finding Aid Conference MNWO Fonds, Series 509/2 Excerpt 4 with Box Lists 500 Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario Conference fonds. -- 1917 - 2004; predominant 1954-1993. – 43m of textual records and other material. The Conference of Manitoba came into existence in June of 1925 with the creation of The United Church of Canada through the union of the Methodist, Presbyterian, Congregational and Local Union Churches of Canada. The name was changed in 1980 to the Conference of Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario as a result of a successful petition to the General Council of the United Church by Cambrian Presbytery. The Conference encompasses the entire province of Manitoba and the area of Northwestern Ontario drained by the Rainy River and Winnipeg River systems as far east as Marathon, Ontario and south to the United States border. The Conference has an administrative as well as a geographic meaning. The thirteen conferences within The United Church of Canada function as a governing body or court of the church. Very simply, they are composed of members of the Order of Ministry on the roll of Presbyteries within the geographical bounds of the Conference and lay persons under appointment to administrative or staff positions within the Conference by a court of the church or the United Church General Council.