Host Specificity of Ambrosia and Bark Beetles (Col., Curculionidae: Scolytinae and Platypodinae) in a New Guinea Rainforest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooklyn, Cloudland, Melsonby (Gaarraay)

BUSH BLITZ SPECIES DISCOVERY PROGRAM Brooklyn, Cloudland, Melsonby (Gaarraay) Nature Refuges Eubenangee Swamp, Hann Tableland, Melsonby (Gaarraay) National Parks Upper Bridge Creek Queensland 29 April–27 May · 26–27 July 2010 Australian Biological Resources Study What is Contents Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a four-year, What is Bush Blitz? 2 multi-million dollar Abbreviations 2 partnership between the Summary 3 Australian Government, Introduction 4 BHP Billiton and Earthwatch Reserves Overview 6 Australia to document plants Methods 11 and animals in selected properties across Australia’s Results 14 National Reserve System. Discussion 17 Appendix A: Species Lists 31 Fauna 32 This innovative partnership Vertebrates 32 harnesses the expertise of many Invertebrates 50 of Australia’s top scientists from Flora 62 museums, herbaria, universities, Appendix B: Threatened Species 107 and other institutions and Fauna 108 organisations across the country. Flora 111 Appendix C: Exotic and Pest Species 113 Fauna 114 Flora 115 Glossary 119 Abbreviations ANHAT Australian Natural Heritage Assessment Tool EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) NCA Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Queensland) NRS National Reserve System 2 Bush Blitz survey report Summary A Bush Blitz survey was conducted in the Cape Exotic vertebrate pests were not a focus York Peninsula, Einasleigh Uplands and Wet of this Bush Blitz, however the Cane Toad Tropics bioregions of Queensland during April, (Rhinella marina) was recorded in both Cloudland May and July 2010. Results include 1,186 species Nature Refuge and Hann Tableland National added to those known across the reserves. Of Park. Only one exotic invertebrate species was these, 36 are putative species new to science, recorded, the Spiked Awlsnail (Allopeas clavulinus) including 24 species of true bug, 9 species of in Cloudland Nature Refuge. -

3.0 Analysis of Trade of Intsia Spp. in New Guinea

3.0 ANALYSIS OF TRADE OF INTSIA SPP. IN NEW GUINEA Prepared by Pius Piskaut, Biology Department, University of Papua New Guinea, P.O Box 320, Waigani, National Capital District, Papua New Guinea. Tel: +675 326 7154, Mobile: 6821885, email: [email protected] April, 2006 FOREWORD Under the Terms of Reference (TOR), it was intended that this Report will cover the whole island of New Guinea. This assertion was based on the distributional range of kwila/merbau and also on allegations of illegal logging on the whole island. Since the island is politically divided into two sovereign nations; Papua New Guinea on the eastern half and Indonesia on the west, it became apparent that data and information specific to the TOR would be difficult to obtain especially in a very short period of time. Much of what is presented in this report is based on data and information collected in Papua New Guinea. Limited data or information obtained from sources in the Indonesian Province of West Papua are incorporated in appropriate sections in the report. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report was made possible with the generous support from TRAFFIC Oceania who funded the merbau/kwila project. As per agreement between WWF South Pacific Programme and TRAFFIC Oceania Inc. (ABN 76 992 979 480) (“TRAFFIC Oceania”) the contract was avoided to the project “Review of trade in selected tropical timber species traded in Germany and the EU”. I would like to acknowledge WWF (PNG) and especially the Project Coordinator, Mr. Ted Mamu who provided me with valuable information and guided me in my write- up. -

Review of Trade in Merbau from Major Range States

REVIEW OF TRADE IN MERBAU FROM MAJOR RANGE STATES TONG P.S.,CHEN, H.K., HEWITT,J.,AND AFFRE A. A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2009 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Tong P.S., Chen, H.K., Hewitt, J., and Affre A. (2009). Review of trade in merbau from major range States TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia ISBN 9789833393176 Cover: Logging truck transporting logs of kwila/merbau Intsia spp., among other species Vanimo, PNG. Photograph credit: James Compton/TRAFFIC Southeast Asia This report is printed in Malaysia using T-Kote, a total chlorine free environmentally friendly paper REVIEW OF TRADE IN MERBAU FROM MAJOR RANGE STATES Tong P.S.,Chen, H.K., Hewitt, J., and Affre A. -

I Is the Sunda-Sahul Floristic Exchange Ongoing?

Is the Sunda-Sahul floristic exchange ongoing? A study of distributions, functional traits, climate and landscape genomics to investigate the invasion in Australian rainforests By Jia-Yee Samantha Yap Bachelor of Biotechnology Hons. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation i Abstract Australian rainforests are of mixed biogeographical histories, resulting from the collision between Sahul (Australia) and Sunda shelves that led to extensive immigration of rainforest lineages with Sunda ancestry to Australia. Although comprehensive fossil records and molecular phylogenies distinguish between the Sunda and Sahul floristic elements, species distributions, functional traits or landscape dynamics have not been used to distinguish between the two elements in the Australian rainforest flora. The overall aim of this study was to investigate both Sunda and Sahul components in the Australian rainforest flora by (1) exploring their continental-wide distributional patterns and observing how functional characteristics and environmental preferences determine these patterns, (2) investigating continental-wide genomic diversities and distances of multiple species and measuring local species accumulation rates across multiple sites to observe whether past biotic exchange left detectable and consistent patterns in the rainforest flora, (3) coupling genomic data and species distribution models of lineages of known Sunda and Sahul ancestry to examine landscape-level dynamics and habitat preferences to relate to the impact of historical processes. First, the continental distributions of rainforest woody representatives that could be ascribed to Sahul (795 species) and Sunda origins (604 species) and their dispersal and persistence characteristics and key functional characteristics (leaf size, fruit size, wood density and maximum height at maturity) of were compared. -

Miocene Diversification in the Savannahs Precedes Tetraploid

Miocene diversification in the Savannahs precedes tetraploid rainforest radiation in the african tree genus Afzelia (Detarioideae, Fabaceae) Armel Donkpegan, Jean-Louis Doucet, Olivier Hardy, Myriam Heuertz, Rosalía Piñeiro To cite this version: Armel Donkpegan, Jean-Louis Doucet, Olivier Hardy, Myriam Heuertz, Rosalía Piñeiro. Miocene diversification in the Savannahs precedes tetraploid rainforest radiation in the african treegenus Afzelia (Detarioideae, Fabaceae). Frontiers in Plant Science, Frontiers, 2020, 11, pp.1-14. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00798. hal-02906073 HAL Id: hal-02906073 https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02906073 Submitted on 24 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License fpls-11-00798 June 17, 2020 Time: 15:14 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 17 June 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00798 Miocene Diversification in the Savannahs Precedes Tetraploid Rainforest Radiation in the African Tree Genus Afzelia (Detarioideae, Fabaceae) Armel S. L. Donkpegan1,2,3*, Jean-Louis -

Ericaceae in Malesia: Vicariance Biogeography, Terrane Tectonics and Ecology

311 Ericaceae in Malesia: vicariance biogeography, terrane tectonics and ecology Michael Heads Abstract Heads, Michael (Science Faculty, University of Goroka, PO Box 1078, Goroka, Papua New Guinea. Current address: Biology Department, University of the South Pacific, P.O. Box 1168, Suva, Fiji. Email: [email protected]) 2003. Ericaceae in Malesia: vicariance biogeography, terrane tectonics and ecology. Telopea 10(1): 311–449. The Ericaceae are cosmopolitan but the main clades have well-marked centres of diversity and endemism in different parts of the world. Erica and its relatives, the heaths, are mainly in South Africa, while their sister group, Rhododendron and relatives, has centres of diversity in N Burma/SW China and New Guinea, giving an Indian Ocean affinity. The Vaccinioideae are largely Pacific-based, and epacrids are mainly in Australasia. The different centres, and trans-Indian, trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic Ocean disjunctions all indicate origin by vicariance. The different main massings are reflected in the different distributions of the subfamilies within Malesia. With respect to plant architecture, in Rhododendron inflorescence bracts and leaves are very different. Erica and relatives with the ‘ericoid’ habit have similar leaves and bracts, and the individual plants may be homologous with inflorescences of Rhododendron. Furthermore, in the ericoids the ‘inflorescence-plant’ has also been largely sterilised, leaving shoots with mainly just bracts, and flowers restricted to distal parts of the shoot. The epacrids are also ‘inflorescence-plants’ with foliage comprised of ‘bracts’, but their sister group, the Vaccinioideae, have dimorphic foliage (leaves and bracts). In Malesian Ericaceae, the four large genera and the family as a whole have most species in the 1500–2000 m altitudinal belt, lower than is often thought and within the range of sweet potato cultivation. -

37610 Dept Enviro Heritage Science Adel Botanic Gardens TEXT 2 Front

© 2008 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium, Government of South Australia J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. 22 (2008) 67–71 © 2008 Department for Environment & Heritage, Government of South Australia A key to Aglaia (Meliaceae) in Australia, with a description of a new species, A. cooperae, from Cape York Peninsula, Queensland Caroline M. Pannell Department of Plant Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3RB, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Abstract An introduction and a key to the 12 species of Aglaia Lour. known from mainland Australia are presented. Aglaia cooperae, endemic to vine thicket on sand on Silver Plains in the Cape York Peninsula of Queensland, is described as new, illustrated and named after the author and naturalist, Wendy Cooper. Introduction The small or tiny flowers are complex in structure and The genus Aglaia Lour., with 120 species currently highly perfumed, especially in male plants. All species recognised, is the largest in the family Meliaceae. It have a fleshy aril. This usually completely surrounds the occurs in Indomalesia, Australasia and the Western seed, but in A. elaeagnoidea from the Kimberley region, Pacific, from India to Samoa and from southwest China it is vestigial and the pericarp is fleshy. The fruits or to northern Australia (Pannell 1992). Twelve species arillate seeds are eaten, and the cleaned seeds dispersed, of these small to medium sized, dioecious, tropical trees have been recorded in northern and north-eastern tropical Australia, mainly on the eastern side of the far north of Queensland, where four or five species are endemic, but also in Kimberley, Arnhem, Carpentaria, Burdekin and Dawson. -

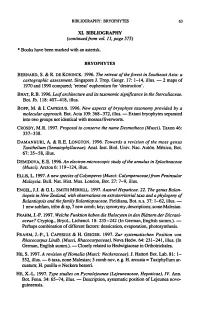

(Continued from Aspects of Bryophyte Provided by Approach. Bot

BIBLIOGRAPHY: BRYOPHYTES 63 XI. Bibliography (continued from vol. 11, page 575) * Books have been marked with an asterisk. BRYOPHYTES BERNARD, S. & R. DE KONINCK. 1996. The retreat of theforest in SoutheastAsia: a cartographic assessment. Singapore J. Trop. Geogr. 17: 1-14, illus. — 2 maps of 1970and 1990compared; ‘retreat’ euphemism for ‘destruction’. BHAT, R.B. 1996. Leaf architecture and its taxonomicsignificance in the Sterculiaceae. Bot. Jb. 118: 407-418, illus. BOPP, M. & I. CAPESIUS. 1996. New aspects of bryophyte taxonomy provided by a molecularapproach. Bot. Acta 109: 368-372, illus. — Extant bryophytes separated mosses/liverworts. into two groups not identical with the Desmotheca CROSBY, M.R. 1997. Proposal to conserve name (Musci). Taxon 46: 337-338. 1996. Towards the DAMANHURI, A. & R.E. LONGTON. a revision of moss genus Taxithelium (Sematophyllaceae). Anal. Inst. Biol. Univ. Nac. Auton. Mexico, Bot. 67: 35-58, illus. DEMIDOVA, E.E. 1996. An electron microscopic study ofthe annulus in Splachnaceae (Musci). Arctoa 6: 119-124, illus. Peninsular ELLIS, L. 1997. A new species of Calymperes (Musci: Calymperaceae) • from Malaysia. Bull. Nat. Hist. Mus. London, Bot. 27: 7-9, illus. G.L. SMITH MERRILL. 1997. Austral 22. The Balan- ENGEL, J.J. & Hepaticae. genus tiopsis in NewZealand, with observations on extraterritorial taxa and a phylogeny of Balantiopsis and thefamily Balantiopsaceae. Fieldiana, Bot. n.s. 37: 1-62, illus. — 1 new subfam, tribe & sp, 7 new comb; key; synonymy, descriptions; some Malesian. FRAHM, J.-P. 1997. Welche Funktion haben die Halocyten in den Blattern der.Dicrani- aceae? Cryptog., Bryol., Lichenol. 18: 235-242 (In German, English summ.). — Perhaps combinationof differentfactors: dessication, evaporation, photosynthesis. -

Diversity and Evolution of Ectomycorrhizal Host Associations in the Sclerodermatineae (Boletales, Basidiomycota)

May 2012 Vol. 194 No. 4 ISSN 0028-646X www.newphytologist.com • New grass phylogeny • Local adaptation in reveals deep evolutionary plant-herbivore interactions relationships & C4 • New method: fast & origins quantitative analysis of • Evolution of stomatal gene expression traits on the road to C4 • Transgenomics tool for photosynthesis identifying genes Research Diversity and evolution of ectomycorrhizal host associations in the Sclerodermatineae (Boletales, Basidiomycota) Andrew W. Wilson, Manfred Binder and David S. Hibbett Department of Biology, Clark University, 950 Main St., Worcester, MA 01610, USA Summary Author for correspondence: • This study uses phylogenetic analysis of the Sclerodermatineae to reconstruct the evolution Andrew W. Wilson of ectomycorrhizal host associations in the group using divergence dating, ancestral range Tel: +1 847 835 6986 and ancestral state reconstructions. Email: [email protected] • Supermatrix and supertree analysis were used to create the most inclusive phylogeny for Received: 15 December 2011 the Sclerodermatineae. Divergence dates were estimated in BEAST. Lagrange was used to Accepted: 5 February 2012 reconstruct ancestral ranges. BAYESTRAITS was used to reconstruct ectomycorrhizal host associ- ations using extant host associations with data derived from literature sources. New Phytologist (2012) • The supermatrix data set was combined with internal transcribed spacer (ITS) data sets for doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04109.x Astraeus, Calostoma, and Pisolithus to produce a 168 operational taxonomic unit (OTU) supertree. The ensuing analysis estimated that basal Sclerodermatineae originated in the late Cretaceous while major genera diversified near the mid Cenozoic. Asia and North America are Key words: ancestral reconstruction, biogeography, boreotropical hypothesis, the most probable ancestral areas for all Sclerodermatineae, and angiosperms, primarily divergence times, ectomycorrhizal evolution, rosids, are the most probable ancestral hosts. -

'The Wet Tropics, Australia's Biological Crown Jewels'

SUSTAINING THE WET TROPICS: A REGIONAL PLAN FOR NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT VOLUME 2A CONDITION REPORT: BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION Nigel Weston1 and Steve Goosem1,2 1Rainforest CRC, Cairns 2Wet Tropics Management Authority, Cairns Established and supported under the Australian Cooperative Research Centres Program © Cooperative Research Centre for Tropical Rainforest Ecology and Management, and FNQ NRM Ltd. ISBN 0 86443 711 0 This work is copyright. The Copyright Act 1968 permits fair dealing for study, research, news reporting, criticism or review. Selected passages, tables or diagrams may be reproduced for such purposes provided acknowledgment of the source is included. Major extracts of the entire document may not be reproduced by any process without written permission of either the Chief Executive Officer, Cooperative Research Centre for Tropical Rainforest Ecology and Management, or Executive Officer, FNQ NRM Ltd. Published by the Cooperative Research Centre for Tropical Rainforest Ecology and Management. Further copies may be obtained from FNQ NRM Ltd, PO Box 1756, Innisfail, QLD, Australia, 4860. This publication should be cited as: Weston, N. and Goosem, S. (2004), Sustaining the Wet Tropics: A Regional Plan for Natural Resource Management, Volume 2A Condition Report: Biodiversity Conservation. Rainforest CRC and FNQ NRM Ltd, Cairns (211 pp). January 2004 Cover Photos: Top: Geoff McDonald Centre: Doug Clague Bottom: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority CONDITION REPORT: BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION i PREFACE Managing natural resources for sustainability and ecosystem health is an obligation of stakeholders at all levels. At the State and Commonwealth government level, there has been a shift over the last few years from the old project-based approach to strategic investment at a regional scale. -

Legume Phylogeny and Classification in the 21St Century: Progress, Prospects and Lessons for Other Species-Rich Clades

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades Legume Phylogeny Working Group ; Bruneau, Anne ; Doyle, Jeff J ; Herendeen, Patrick ; Hughes, Colin E ; Kenicer, Greg ; Lewis, Gwilym ; Mackinder, Barbara ; Pennington, R Toby ; Sanderson, Michael J ; Wojciechowski, Martin F ; Koenen, Erik Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-78167 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Legume Phylogeny Working Group; Bruneau, Anne; Doyle, Jeff J; Herendeen, Patrick; Hughes, Colin E; Kenicer, Greg; Lewis, Gwilym; Mackinder, Barbara; Pennington, R Toby; Sanderson, Michael J; Wojciechowski, Martin F; Koenen, Erik (2013). Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades. Taxon, 62(2):217-248. TAXON 62 (2) • April 2013: 217–248 LPWG • Legume phylogeny and classification REVIEWS Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: Progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades The Legume Phylogeny Working Group1 This paper was compiled by Anne Bruneau,2 Jeff J. Doyle,3 Patrick Herendeen,4 Colin Hughes,5 Greg Kenicer,6 Gwilym Lewis,7 Barbara Mackinder,6,7 R. Toby Pennington,6 Michael J. Sanderson8 and Martin F. Wojciechowski9 who were equally responsible and listed here in alphabetical order only, with contributions from Stephen Boatwright,10 Gillian Brown,11 Domingos Cardoso,12 Michael Crisp,13 Ashley Egan,14 Renée H. Fortunato,15 Julie Hawkins,16 Tadashi Kajita,17 Bente Klitgaard,7 Erik Koenen,5 Matt Lavin18, Melissa Luckow,3 Brigitte Marazzi,8 Michelle M. -

37610 Dept Enviro Heritage Science Adel Botanic Gardens TEXT 2 Front

JOURNAL of the ADELAIDE BOTANIC GARDENS AN OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL FOR AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY flora.sa.gov.au/jabg Published by the STATE HERBARIUM OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA on behalf of the BOARD OF THE BOTANIC GARDENS AND STATE HERBARIUM © Board of the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, Adelaide, South Australia © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia All rights reserved State Herbarium of South Australia PO Box 2732 Kent Town SA 5071 Australia © 2008 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium, Government of South Australia J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. 22 (2008) 67–71 © 2008 Department for Environment & Heritage, Government of South Australia A key to Aglaia (Meliaceae) in Australia, with a description of a new species, A. cooperae, from Cape York Peninsula, Queensland Caroline M. Pannell Department of Plant Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3RB, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Abstract An introduction and a key to the 12 species of Aglaia Lour. known from mainland Australia are presented. Aglaia cooperae, endemic to vine thicket on sand on Silver Plains in the Cape York Peninsula of Queensland, is described as new, illustrated and named after the author and naturalist, Wendy Cooper. Introduction The small or tiny flowers are complex in structure and The genus Aglaia Lour., with 120 species currently highly perfumed, especially in male plants. All species recognised, is the largest in the family Meliaceae. It have a fleshy aril. This usually completely surrounds the occurs in Indomalesia, Australasia and the Western seed, but in A.