A Juggler on the Moon: How Sounds Think in Tom Stoppard's Darkside Neil Verma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Hitchhiker-By-Lucille-Fletcher

1 Short Story of the Month Table of Contents "The Hitchhiker" by Lucille Fletcher Terms of Use 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Activities, Difficulty Levels, and Common Core Alignment 4 Digital Components/Google Classroom Guide 5 Teaching Guide, Rationale, Lesson Plans, and Procedures: EVERYTHING 6-11 Activity 1: Story Devices Interactive Notebook Lesson 12-14 Activity 2: Story Devices Practice w/Key 15-18 Activity 3: Hitchhiker Play Prep Instructions & Role Sheet 19-20 Activity 6: Annotation Guide (Story Devices) 21-23 Activity 7: Basic Comprehension Quiz (Recall Facts and Details) w Key 24-25 Activity 9: Audio Analysis Guide w/Key 26-27 Activity 10: Find Evidence That… Text-Dependent Questions Activity w/Key 28-29 Activity 11: Diagramming a Story Organizer w/Answer Key 30-31 Activity 12: Plot Diagram Quiz w/Key 32-33 Activity 13: Vocabulary Guide – Standardized Test Vocabulary Practice w/Key 34-37 Activity 14: Story Analysis: Plot Development Questions w/Key 38-39 Activity 15: The Hitchhiker Video Analysis w/Key 40-47 Activity 16: Comprehension Skills Test 48-53 Activity 17: Write a Narrative Ending Prewriting Organizer & Rubric 54-55 Activity 18: Nonfiction Paired Text: “Why Is Fear Fun?” 56 Activity 19: Nonfiction Skills Analysis Activity 57-60 Activity 20: Essential Question (Putting It All Together) 61-62 TEKS Alignment 63 3 ©2017 erin cobb imlovinlit.com Short Story of the Month Teacher’s Guide "The Hitchhiker" by Lucille Fletcher Activities, Difficulty Levels, and Common Core Alignment List of Activities & Standards Difficulty Level: *Easy **Moderate ***Challenge Activity 1: Story Devices Lesson** RL.6.3, RL.6.5 Activity 2: Story Devices Practice** RL.6.3, RL.6.5 Activity 3: Hitchhiker Play Prep* SL.6.1, SL.6.2 Activity 4: Journal Activity* SL.6.1 Activity 5: First Read: Play Performance** SL.6.1, SL.6.2, SL.6.5 Activity 6: Annotation Guide (Story Devices)** RL.6.1, RL.6.3, RL.6.5 Activity 7: Comprehension Quiz* RL.6.1 Activity 8: Radio Play Audio Performance* SL.6.2, RL.6.1, RL.6.3 Activity 9: Audio Analysis Guide** RL.6.7. -

The Hitchhiker by Lucille Fletcher.Pdf

The Hitchhiker By Lucille Fletcher ORSON WELLES: Personally, I've never met anybody who didn't like a good ghost story. But I know a lot of people who think there are a lot of people who don't like a good ghost story. For the benefit of these, at least, I go on record at the outset of this evening's entertainment with a sober assurance that, although blood may be curdled on this program, none will be spilt. There's no shooting, knifing, throttling, axing or poisoning here. No clanking chains, no cobwebs, no bony and/or hairy hands appearing from secret panels or, better yet, bedroom curtains. If it's any part of that dear old phosphorescent foolishness that people who don't like ghost stories don't like ... MUSIC: GENTLY OUT WELLES: ... then, again I promise you, we haven't got it. Not tonight. What we DO have is a thriller. If it's half as good as we think it is, you can call it a shocker. It's already been called "a real Orson Welles story." Now, frankly, I don't know what this means. I've been on the air, directing and acting in my own shows for quite a while now and I don't suppose I've done more than half a dozen thrillers in all that time. Honestly, I don't think even THAT many. But it seems I do have a reputation for the uncanny. Quite possibly, a little escapade of mine, involving a couple of planets which shall be nameless, is responsible. -

Talking Book Topics November-December 2017

Talking Book Topics November–December 2017 Volume 83, Number 6 Need help? Your local cooperating library is always the place to start. For general information and to order books, call 1-888-NLS-READ (1-888-657-7323) to be connected to your local cooperating library. To find your library, visit www.loc.gov/nls and select “Find Your Library.” To change your Talking Book Topics subscription, contact your local cooperating library. Get books fast from BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site. To use BARD, contact your local cooperating library or visit nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. The free BARD Mobile app is available from the App Store, Google Play, and Amazon’s Appstore. About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics, published in audio, large print, and online, is distributed free to people unable to read regular print and is available in an abridged form in braille. Talking Book Topics lists titles recently added to the NLS collection. The entire collection, with hundreds of thousands of titles, is available at www.loc.gov/nls. Select “Catalog Search” to view the collection. Talking Book Topics is also online at www.loc.gov/nls/tbt and in downloadable audio files from BARD. Overseas Service American citizens living abroad may enroll and request delivery to foreign addresses by contacting the NLS Overseas Librarian by phone at (202) 707-9261 or by email at [email protected]. Page 1 of 128 Music scores and instructional materials NLS music patrons can receive braille and large-print music scores and instructional recordings through the NLS Music Section. -

9781412929998.Pdf

Duck-3494-Prelims.qxd 1/16/2007 10:39 AM Page i Human Relationships Duck-3494-Prelims.qxd 1/16/2007 10:39 AM Page ii Duck-3494-Prelims.qxd 1/16/2007 10:39 AM Page iii Human Relationships 4th Edition Steve Duck Duck-3494-Prelims.qxd 1/16/2007 10:39 AM Page iv © Steve Duck 2007 First published 2007 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP SAGE Publications Inc. 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B 1/I 1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area Mathura Road, New Delhi 110 044 India SAGE Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd 33 Pekin Street #02-01 Far East Square Singapore 048763 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-4129-2998-1 ISBN 978-1-4129-2999-8 (pbk) Library of Congress Control Number: 2006929060 Typeset by C&M Digitals (P) Ltd, Chennai, India Printed in Great Britain by The Alden Press, Witney Printed on paper from sustainable resources Duck-3494-Prelims.qxd 1/16/2007 -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Park-Finch, Heebon Title: Hypertextuality and polyphony in Tom Stoppard's stage plays General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Hypertextuality and Polyphony in Tom Stoppard's Stage Plays Heebon Park-Finch A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in -

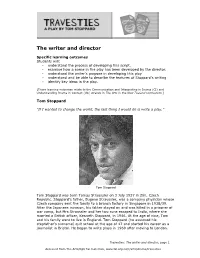

The Writer and Director

The writer and director Specific learning outcomes Students will: • understand the process of developing this script. • examine how a scene in the play has been developed by the director. • understand the writer’s purpose in developing this play • understand and be able to describe the features of Stoppard’s writing • identify key ideas in the play. [These learning outcomes relate to the Communication and Interpreting in Drama (CI) and Understanding Drama in Context (UC) strands in The Arts in the New Zealand Curriculum.] Tom Stoppard “If I wanted to change the world, the last thing I would do is write a play.” Tom Stoppard Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler on 3 July 1937 in Zlín, Czech Republic. Stoppard’s father, Eugene Straussler, was a company physician whose Czech company sent the family to a branch factory in Singapore in 1938/39. After the Japanese invasion, his father stayed on and was killed in a prisoner of war camp, but Mrs Straussler and her two sons escaped to India, where she married a British officer, Kenneth Stoppard, in 1946. At the age of nine, Tom and his family went to live in England. Tom Stoppard (he assumed his stepfather’s surname) quit school at the age of 17 and started his career as a journalist in Bristol. He began to write plays in 1960 after moving to London. Travesties: The writer and director, page 1 Accessed from The Arts/Ngā Toi materials, www.tki.org.nz/r/arts/drama/travesties Stoppard’s bibliography of plays, radio dramas and film scripts is extensive. -

For Those Who Won't Fail Themselves

~For Those Who Won’t Fail Themselves~ Black Sun Imperium 2 Mine is a Heart of Carnelian, Crimson as Murder on a Holy Day. Mine is a Heart of Corneal, the Gnarled Roots of a Dogwood and the Bursting of Flowers. I am the Broken Wax Seal on my Lover's Letters. I am the Phoenix, the Fiery Sun, Consuming and Resuming Myself. I Will what I Will. Mine is a Heart of Carnelian, Blood Red as the Crest of a Phoenix. ~To My Beloved Master Enlil Hiro-kura Hoshigaoka~ 3 Phagos Angmar Hoshigaoka Black Sun Imperium Bringing Forth the Noesis of the Ancient Darklords 4 Black Sun Imperium Index Foreword ………………………………….. 7 Preface …………………………………... 9 Imperium of the Black Sun …………………………………On 16 The Deathtrap of Mental Inertia: The Yoke of the Herd ………………………………. Two 26 The Black Sun ……………………………… . Thr 35 Darklords in Disguise ……………………………… Four 55 The 5 Second Rule ……………………………… Fi 91 The Abysmal Bridge ………………………………… Six 100 The Bridge of Manifestation ………………………………… S n 122 Prelude to the Styx ………………………………… ight 130 The Styx ov Power ………………………………… Nin 144 The Styx ov Wealth ………………………………… Ten 199 The Styx ov Eminence ………………………………… le n 220 The Styx ov Strife ………………………………… Twl 252 The Nine Pointed Star Black Sun Working ………………………………… . 13 266 Glossary ………………………………….. 274 List of Resources …………………………………… 277 5 6 Foreword Foreword from the Editor When first I was asked to proof read and correct this book, I had no idea what to expect; I myself was an open book as far as this subject was concerned. Always a fan of Darkside characters but never having done too much research into the subject, I had no formed opinions and absolutely no idea there was a culture dedicated to living life in this manner. -

Works by Tom Stoppard

Works by Tom Stoppard ‘A Play In Three Acts’ 56n, 463n, 581n, 582n Dogg’s Hamlet, Cahoot’s Macbeth xxiv, A Separate Peace 499, 528n xxvi, 55, 176, 354n, 393, 423, 557, 582 A Walk on the Water 516 After Magritte xxxi, 5, 8–11, 18, 39, 55–56, Empire of the Sun 7, 414, 440n 437, 470, 491, 504, 504n, 535n, 581 Enigma 77 Albert’s Bridge 155, 551 Enter a Free Man 254, 399, 454, 516n, 524, Anna Karenina 257 560, 560n, 583 Another Moon Called Earth 37n, 121, 156, 239, Every Good Boy Deserves Favour xxv–xxvi, 239n, 320, 323, 441, 443, 455, 582 xxix, 50–52, 55, 56, 59n, 90, 121, 136, Arcadia xxii, xxiv–xvii, 15, 17, 23, 37, 182–184, 235–237, 286–289, 294, 298, 38–41, 55, 74–79, 88, 88n, 118n, 126, 327n, 381–384, 437, 447, 473, 479, 136–152, 179, 185, 212, 222, 231, 234, 238, 490, 496n, 582 248, 260, 309, 313, 315, 322, 337, 347, 350–352, 369, 377n, 398n, 399, 407, ‘First Person’ 244n 412, 418, 424, 436n, 441, 451, 470, 473, ‘Freedom but thousands are still 488–489, 505, 514, 521, 523, captive’ 277n 531, 552, 566, 568–572, 575, 578–579, Funny Man 458, 559 581, 583 Article on James Thurber 5 Galileo 144, 258–259, 260, 471 Artist Descending a Staircase xxiii, xxvi, 11–14, 26, 62, 63, 64, 64n, 66, 118, 120–121, Hapgood xxiii–xxvi, xxvii–xxix, 15, 40, 153n, 157–159, 236n, 238, 326, 329, 352, 52, 55, 56, 127, 129, 135–137, 143, 145, 363, 370–372, 423, 533, 551, 560–565, 222n, 238, 258, 259n, 260, 309, 343, 347, 579, 582 349, 351, 362, 365–369, 398n, 400–407, 400n, 423–424, 426, 428, 471, 478, 488, ‘But For The Middle Classes’ 251n, 261n, 492–495, 502–503, -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases and gifts, 1991-2000 Processed by Katherine Mosley, 1993-2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Biographical Sketch Playwright Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Zlin, Czechoslovakia, on July 3, 1937. However, he lived in Czechoslovakia only until 1939, when his family moved to Singapore. Stoppard, his mother, and his older brother were evacuated to India shortly before the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1941; his father, Eugene Straussler, remained behind and was killed. In 1946, Stoppard's mother, Martha, married British army officer Kenneth Stoppard and the family moved to England, eventually settling in Bristol. Stoppard left school at the age of seventeen and began working as a journalist, first with the Western Daily Press (1954-58) and then with the Bristol Evening World (1958-60). -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English. Arrangement Due to size, this inventory has been divided into two separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Tom Stoppard Papers--Series descriptions and Series I. through Series II. [Part I] Tom Stoppard Papers--Series III. through Series V. and Indices [Part II] [This page] Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Series III. Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd 19 boxes Subseries A: General Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd By Date 1968-2000, nd Container 124.1-5 1994, nd Container 66.7 "Miscellaneous," Aug. 1992-Nov. 1993 Container 53.4 Copies of outgoing letters, 1989-91 Container 125.3 Copies of outgoing -

Usuba, Optimizing Bitslicing Compiler Darius Mercadier

Usuba, Optimizing Bitslicing Compiler Darius Mercadier To cite this version: Darius Mercadier. Usuba, Optimizing Bitslicing Compiler. Programming Languages [cs.PL]. Sorbonne Université (France), 2020. English. tel-03133456 HAL Id: tel-03133456 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03133456 Submitted on 6 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE` DE DOCTORAT DE SORBONNE UNIVERSITE´ Specialit´ e´ Informatique Ecole´ doctorale Informatique, Tel´ ecommunications´ et Electronique´ (Paris) Present´ ee´ par Darius MERCADIER Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR de SORBONNE UNIVERSITE´ Sujet de la these` : Usuba, Optimizing Bitslicing Compiler soutenue le 20 novembre 2020 devant le jury compose´ de : M. Gilles MULLER Directeur de these` M. Pierre-Evariste´ DAGAND Encadrant de these` M. Karthik BHARGAVAN Rapporteur Mme. Sandrine BLAZY Rapporteur Mme. Caroline COLLANGE Examinateur M. Xavier LEROY Examinateur M. Thomas PORNIN Examinateur M. Damien VERGNAUD Examinateur Abstract Bitslicing is a technique commonly used in cryptography to implement high-throughput parallel and constant-time symmetric primitives. However, writing, optimizing and pro- tecting bitsliced implementations by hand are tedious tasks, requiring knowledge in cryptography, CPU microarchitectures and side-channel attacks. The resulting programs tend to be hard to maintain due to their high complexity. -

A Theory of Consumer Fraud in Market Economies

A THEORY OF FRAUD IN MARKET ECONOMIES ADISSERTATIONIN Economics and Social Science Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Nicola R. Matthews B.F.A, School of Visual Arts, 2002 M.A., State University College Bu↵alo, 2009 Kansas City, Missouri 2018 ©2018 Nicola R. Matthews All Rights Reserved A THEORY OF FRAUD IN MARKET ECONOMIES Nicola R. Matthews, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2018 ABSTRACT Of the many forms of human behavior, perhaps none more than those of force and fraud have caused so much harm in both social and ecological environments. In spite of this, neither shows signs of weakening given their current level of toleration. Nonetheless, what can be said in respect to the use of force in the West is that it has lost most of its competitiveness. While competitive force ruled in the preceding epoch, this category of violence has now been reduced to a relatively negligible degree. On the other hand, the same cannot be said of fraud. In fact, it appears that it has moved in the other direction and become more prevalent. The causes for this movement will be the fundamental question directing the inquiry. In the process, this dissertation will trace historical events and methods of control ranging from the use of direct force, to the use of ceremonies and rituals and to the use of the methods of law. An additional analysis of transformation will also be undertaken with regards to risk-sharing-agrarian-based societies to individual-risk-factory-based ones.