Panulirus Argus (Caribbean Spiny Lobster)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade AUSTIN B. WILLIAMS Introduction tons to pounds to conform with US. tinents and islands, shoal platforms, and fishery statistics). This total includes certain seamounts (Fig. 1 and 2). More Lobsters are valued throughout the clawed lobsters, spiny and flat lobsters, over, the world distribution of these world as prime seafood items wherever and squat lobsters or langostinos (Tables animals can also be divided rougWy into they are caught, sold, or consumed. 1 and 2). temperate, subtropical, and tropical Basically, three kinds are marketed for Fisheries for these animals are de temperature zones. From such partition food, the clawed lobsters (superfamily cidedly concentrated in certain areas of ing, the following facts regarding lob Nephropoidea), the squat lobsters the world because of species distribu ster fisheries emerge. (family Galatheidae), and the spiny or tion, and this can be recognized by Clawed lobster fisheries (superfamily nonclawed lobsters (superfamily noting regional and species catches. The Nephropoidea) are concentrated in the Palinuroidea) . Food and Agriculture Organization of temperate North Atlantic region, al The US. market in clawed lobsters is the United Nations (FAO) has divided though there is minor fishing for them dominated by whole living American the world into 27 major fishing areas for in cooler waters at the edge of the con lobsters, Homarus americanus, caught the purpose of reporting fishery statis tinental platform in the Gul f of Mexico, off the northeastern United States and tics. Nineteen of these are marine fish Caribbean Sea (Roe, 1966), western southeastern Canada, but certain ing areas, but lobster distribution is South Atlantic along the coast of Brazil, smaller species of clawed lobsters from restricted to only 14 of them, i.e. -

Factors Affecting Growth of the Spiny Lobsters Panulirus Gracilis and Panulirus Inflatus (Decapoda: Palinuridae) in Guerrero, México

Rev. Biol. Trop. 51(1): 165-174, 2003 www.ucr.ac.cr www.ots.ac.cr www.ots.duke.edu Factors affecting growth of the spiny lobsters Panulirus gracilis and Panulirus inflatus (Decapoda: Palinuridae) in Guerrero, México Patricia Briones-Fourzán and Enrique Lozano-Álvarez Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Unidad Académica Puerto Morelos. P. O. Box 1152, Cancún, Q. R. 77500 México. Fax: +52 (998) 871-0138; [email protected] Received 00-XX-2002. Corrected 00-XX-2002. Accepted 00-XX-2002. Abstract: The effects of sex, injuries, season and site on the growth of the spiny lobsters Panulirus gracilis, and P. inflatus, were studied through mark-recapture techniques in two sites with different ecological characteristics on the coast of Guerrero, México. Panulirus gracilis occurred in both sites, whereas P. inflatus occurred only in one site. All recaptured individuals were adults. Both species had similar intermolt periods, but P. gracilis had significantly higher growth rates (mm carapace length week-1) than P. inflatus as a result of a larger molt incre- ment. Growth rates of males were higher than those of females in both species owing to larger molt increments and shorter intermolt periods in males. Injuries had no effect on growth rates in either species. Individuals of P. gracilis grew faster in site 1 than in site 2. Therefore, the effect of season on growth of P. gracilis was analyzed separately in each site. In site 2, growth rates of P. gracilis were similar in summer and in winter, whereas in site 1 both species had higher growth rates in winter than in summer. -

Lobsters LOBSTERS§

18 Lobsters LOBSTERS§ All species are of high commercial value locally and internationally. Five species occur in reasonable numbers in Kenya: Panulirus homarus, Panulirus ornatus, Panulirus versicolor, Panulirus penicillatus and Panulirus longipes. These are caughtungravid along and the the coast young by weighing the artisanal more fishing than 250 fleet. g. Landings One species, of these Puerulus species angulatus are highest in the north coast particularly the Islands of Lamu District. The fishery has been declining,Scyllaridae. but currently The latter the fishermen are also caught are only as by–catch allowed toby landshallow the , is caught by the industrial fishing fleet in off–shore waters, as well as members of the family water prawn trawling but areTECHNICAL commercially unimportant, TERMS AND utilized MEASUREMENTS as food fish by local people. and whip–like antennal flagellum long carapace length tail length pereiopod uropod frontal telson horn III III IV VIV abdominal segments tail fan body length antennule (BL) antennular plate strong spines on carapace PALINURIDAE antenna carapace length abdomen tail fan antennal flagellum a broad, flat segment antennules eye pereiopod 1 pereiopod 5 pereiopod 2 SCYLLARIDAE pereiopod 3 pereiopod 4 Guide to Families 19 GUIDE TO FAMILIES NEPHROPIDAE Page 20 True lobsters § To about 15 cm. Marine, mainly deep waters on soft included in the Guide to Species. 1st pair of substrates. Three species of interest to fisheriespereiopods are large 3rd pair of pereiopods with chela PALINURIDAE Page 21 Antennal Spiny lobsters § To about 50 cm. Marine, mostly shallow waters on flagellum coral and sand stone reefs, some species on soft included in the Guide to Species. -

Decapod Crustacean Grooming: Functional Morphology, Adaptive Value, and Phylogenetic Significance

Decapod crustacean grooming: Functional morphology, adaptive value, and phylogenetic significance N RAYMOND T.BAUER Center for Crustacean Research, University of Southwestern Louisiana, USA ABSTRACT Grooming behavior is well developed in many decapod crustaceans. Antennular grooming by the third maxillipedes is found throughout the Decapoda. Gill cleaning mechanisms are qaite variable: chelipede brushes, setiferous epipods, epipod-setobranch systems. However, microstructure of gill cleaning setae, which are equipped with digitate scale setules, is quite conservative. General body grooming, performed by serrate setal brushes on chelipedes and/or posterior pereiopods, is best developed in decapods at a natant grade of body morphology. Brachyuran crabs exhibit less body grooming and virtually no specialized body grooming structures. It is hypothesized that the fouling pressures for body grooming are more severe in natant than in replant decapods. Epizoic fouling, particularly microbial fouling, and sediment fouling have been shown r I m ans of amputation experiments to produce severe effects on olfactory hairs, gills, and i.icubated embryos within short lime periods. Grooming has been strongly suggested as an important factor in the coevolution of a rhizocephalan parasite and its anomuran host. The behavioral organization of grooming is poorly studied; the nature of stimuli promoting grooming is not understood. Grooming characters may contribute to an understanding of certain aspects of decapod phylogeny. The occurrence of specialized antennal grooming brushes in the Stenopodidea, Caridea, and Dendrobranchiata is probably not due to convergence; alternative hypotheses are proposed to explain the distribution of this grooming character. Gill cleaning and general body grooming characters support a thalassinidean origin of the Anomura; the hypothesis of brachyuran monophyly is supported by the conservative and unique gill-cleaning method of the group. -

A Time Series of California Spiny Lobster (Panulirus Interruptus) Phyllosoma from 1951 to 2008 Links Abundance to Warm Oceanogr

KOSLOW ET AL.: LOBSTER PHYLLOSOMA ABUNDANCE LINKED TO WARM CONDITIONS CalCOFI Rep., Vol. 53, 2012 A TIME SERIES OF CALIFORNIA SPINY LOBSTER (PANULIRUS INTERRUPTUS) PHYLLOSOMA FROM 1951 TO 2008 LINKS ABUNDANCE TO WARM OCEANOGRAPHIC CONDITIONS IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA J. ANTHONY KOSLOW LauRA ROGERS-BENNETT DOUGLAS J. NEILSON Scripps Institution of Oceanography California Department of Fish and Game California Department of Fish and Game University of California, S.D. Bodega Marine Laboratory 4949 Viewridge Avenue La Jolla, CA 92093-0218 UC Davis, 2099 Westside Rd. San Diego, CA 92123 ph: (858) 534-7284 Bodega Bay, CA 94923-0247 [email protected] ABSTRACT The California spiny lobster (Panulirus interruptus) population is the basis for a valuable commercial and recreational fishery off southern California, yet little is known about its population dynamics. Studies based on CalCOFI sampling in the 1950s indicated that the abun- dance of phyllosoma larvae may be sensitive to ocean- ographic conditions such as El Niño events. To further study the potential influence of environmental variabil- ity and the fishery on lobster productivity, we developed a 60-year time series of the abundance of lobster phyl- losoma from the historical CalCOFI sample collection. Phyllosoma were removed from the midsummer cruises when the early-stage larvae are most abundant in the plankton nearshore. We found that the abundance of the early-stage phyllosoma displayed considerable inter- annual variability but was significantly positively corre- Figure 1. Commercial (solid circles), recreational (open triangles), and total lated with El Niño events, mean sea-surface temperature, landings (solid line) of spiny lobster off southern California. -

Neurolipofuscin Is a Measure of Age in the Caribbean Spiny Lobster, Panulirus Argus, in Florida

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Biology Theses Department of Biology 8-3-2006 Neurolipofuscin is a Measure of Age in the Caribbean Spiny Lobster, Panulirus argus, in Florida Kerry Elizabeth Maxwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/biology_theses Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Maxwell, Kerry Elizabeth, "Neurolipofuscin is a Measure of Age in the Caribbean Spiny Lobster, Panulirus argus, in Florida." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/biology_theses/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEUROLIPOFUSCIN IS A MEASURE OF AGE IN THE CARIBBEAN SPINY LOBSTER, PANULIRUS ARGUS, IN FLORIDA. by KERRY E. MAXWELL Under the direction of Charles D. Derby ABSTRACT Accurate age estimates for the commercially-important Caribbean spiny lobster, Panulirus argus, would greatly enhance analyses of life history and population dynamics. Previous estimates of their age based on size and growth may be inaccurate because of variable growth in the wild. An established technique for aging crustaceans – histologically-determined lipofuscin content in the nervous system – was used on lobsters reared in the laboratory for up to five years. We verified the presence of lipofuscin in eyestalk neural tissue and described its distribution in cell cluster A of the hemiellipsoid body. Neurolipofuscin content of both sexes increased linearly over the five-year age range, with seasonal oscillations. -

Balanus Trigonus

Nauplius ORIGINAL ARTICLE THE JOURNAL OF THE Settlement of the barnacle Balanus trigonus BRAZILIAN CRUSTACEAN SOCIETY Darwin, 1854, on Panulirus gracilis Streets, 1871, in western Mexico e-ISSN 2358-2936 www.scielo.br/nau 1 orcid.org/0000-0001-9187-6080 www.crustacea.org.br Michel E. Hendrickx Evlin Ramírez-Félix2 orcid.org/0000-0002-5136-5283 1 Unidad académica Mazatlán, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. A.P. 811, Mazatlán, Sinaloa, 82000, Mexico 2 Oficina de INAPESCA Mazatlán, Instituto Nacional de Pesca y Acuacultura. Sábalo- Cerritos s/n., Col. Estero El Yugo, Mazatlán, 82112, Sinaloa, Mexico. ZOOBANK http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:74B93F4F-0E5E-4D69- A7F5-5F423DA3762E ABSTRACT A large number of specimens (2765) of the acorn barnacle Balanus trigonus Darwin, 1854, were observed on the spiny lobster Panulirus gracilis Streets, 1871, in western Mexico, including recently settled cypris (1019 individuals or 37%) and encrusted specimens (1746) of different sizes: <1.99 mm, 88%; 1.99 to 2.82 mm, 8%; >2.82 mm, 4%). Cypris settled predominantly on the carapace (67%), mostly on the gastric area (40%), on the left or right orbital areas (35%), on the head appendages, and on the pereiopods 1–3. Encrusting individuals were mostly small (84%); medium-sized specimens accounted for 11% and large for 5%. On the cephalothorax, most were observed in branchial (661) and orbital areas (240). Only 40–41 individuals were found on gastric and cardiac areas. Some individuals (246), mostly small (95%), were observed on the dorsal portion of somites. -

On the Vaccination of Shrimp Against White Spot Syndrome Virus

On the vaccination of shrimp against white spot syndrome virus Jeroen Witteveldt Promotoren: Prof. dr. J. M. Vlak Persoonlijk Hoogleraar bij de Leerstoelgroep Virologie Prof. dr. R. W. Goldbach Hoogleraar in de Virologie Co-promotor Dr. ir. M. C. W. van Hulten (Wetenschappelijk medewerker CSIRO, Brisbane, Australia) Promotiecommissie Prof. dr. P. Sorgeloos (Universiteit Gent, België) Prof. dr. J. A. J. Verreth (Wageningen Universiteit) Prof. dr. ir. H. F. J. Savelkoul (Wageningen Universiteit) Dr. ir. J. T. M. Koumans (Intervet International, Boxmeer, Nederland) Dit onderzoek werd uitgevoerd binnnen de onderzoekschool ‘Production Ecology and Resource Conservation’ (PE&RC) On the vaccination of shrimp against white spot syndrome virus Jeroen Witteveldt Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op het gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. dr. M. J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 6 januari 2006 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula Jeroen Witteveldt (2006) On the vaccination of shrimp against white spot syndrome virus Thesis Wageningen University – with references – with summary in Dutch ISBN: 90-8504-331-X Subject headings: WSSV, vaccination, immunology, Nimaviridae, Penaeus monodon CONTENTS Chapter 1 General introduction 1 Chapter 2 Nucleocapsid protein VP15 is the basic DNA binding protein of 17 white spot syndrome virus of shrimp Chapter 3 White spot syndrome virus envelope protein VP28 is involved in the 31 systemic infection of shrimp Chapter 4 Re-assessment of the neutralization -

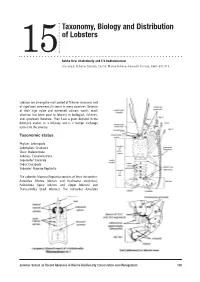

Taxonomy, Biology and Distribution of Lobsters

Taxonomy, Biology and Distribution of Lobsters 15 Rekha Devi Chakraborty and E.V.Radhakrishnan Crustacean Fisheries Division, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi-682 018 Lobsters are among the most prized of fisheries resources and of significant commercial interest in many countries. Because of their high value and esteemed culinary worth, much attention has been paid to lobsters in biological, fisheries, and systematic literature. They have a great demand in the domestic market as a delicacy and is a foreign exchange earner for the country. Taxonomic status Phylum: Arthropoda Subphylum: Crustacea Class: Malacostraca Subclass: Eumalacostraca Superorder: Eucarida Order: Decapoda Suborder: Macrura Reptantia The suborder Macrura Reptantia consists of three infraorders: Astacidea (Marine lobsters and freshwater crayfishes), Palinuridea (Spiny lobsters and slipper lobsters) and Thalassinidea (mud lobsters). The infraorder Astacidea Summer School on Recent Advances in Marine Biodiversity Conservation and Management 100 Rekha Devi Chakraborty and E.V.Radhakrishnan contains three superfamilies of which only one (the Infraorder Palinuridea, Superfamily Eryonoidea, Family Nephropoidea) is considered here. The remaining two Polychelidae superfamilies (Astacoidea and parastacoidea) contain the 1b. Third pereiopod never with a true chela,in most groups freshwater crayfishes. The superfamily Nephropoidea (40 chelae also absent from first and second pereiopods species) consists almost entirely of commercial or potentially 3a Antennal flagellum reduced to a single broad and flat commercial species. segment, similar to the other antennal segments ..... Infraorder Palinuridea, Superfamily Palinuroidea, The infraorder Palinuridea also contains three superfamilies Family Scyllaridae (Eryonoidea, Glypheoidea and Palinuroidea) all of which are 3b Antennal flagellum long, multi-articulate, flexible, whip- marine. The Eryonoidea are deepwater species of insignificant like, or more rigid commercial interest. -

Large Spiny Lobsters Reduce the Catchability of Small Conspecifics

Vol. 666: 99–113, 2021 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published May 20 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13695 Mar Ecol Prog Ser OPEN ACCESS Size matters: large spiny lobsters reduce the catchability of small conspecifics Emma-Jade Tuffley1,2,3,*, Simon de Lestang2, Jason How2, Tim Langlois1,3 1School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia 2Aquatic Science and Assessment, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, 39 Northside Drive, Hillarys, WA 6025, Australia 3The UWA Oceans Institute, Indian Ocean Marine Research Centre, Cnr. of Fairway and Service Road 4, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia ABSTRACT: Indices of lobster abundance and population demography are often derived from pot catch rate data and rely upon constant catchability. However, there is evidence in clawed lobsters, and some spiny lobsters, that catchability is affected by conspecifics present in pots, and that this effect is sex- and size-dependent. For the first time, this study investigated this effect in Panulirus cyg nus, an economically important spiny lobster species endemic to Western Australia. Three studies: (1) aquaria trials, (2) pot seeding experiments, and (3) field surveys, were used to investi- gate how the presence of large male and female conspecifics influence catchability in smaller, immature P. cygnus. Large P. cygnus generally reduced the catchability of small conspecifics; large males by 26−33% and large females by 14−27%. The effect of large females was complex and varied seasonally, dependent on the sex of the small lobster. Conspecific-related catchability should be a vital consideration when interpreting the results of pot-based surveys, especially if population demo graphy changes. -

Magnetic Remanence in the Western Atlantic Spiny Lobster, Panulirus Argus

J. exp. Biol. 113, 29-41 (1984) 29 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1984 MAGNETIC REMANENCE IN THE WESTERN ATLANTIC SPINY LOBSTER, PANULIRUS ARGUS BY KENNETH J. LOHMANN* Department of Zoology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, U.SA. and C. V. Whitney Laboratory for Experimental Marine Biology and Medicine, University of Florida, Route 1, Box 121, St Augustine, FL 32086, U.SA. Accepted 3 May 1984 SUMMARY The magnetic characteristics of 15 western Atlantic spiny lobsters (Panulirus argus) were analysed with a superconducting cryogenic magnetometer. Each specimen possessed a significant natural remanent magnetization (NRM) and isothermal remanent magnetization (IRM), in- dicating that ferromagnetic material is present. Analyses of the distribution of total remanence and mass-specific remanence indicate that magnetic material is concentrated in the cephalothorax, particularly in tissue associated with the fused thoracic ganglia. Mass-specific remanence and the total quantity of magnetic material in the cephalothorax and abdomen both increase as functions of carapace length. The NRM is significantly orientated in at least four regions of the body. The NRM of the left half of the posterior cephalothorax is directed pos- teriorly, while that of the right half is orientated anteriorly. In addition, the NRM of the middle cephalothorax is orientated toward the right side of the animal; the NRM of the telson-uropods region is directed toward the left. The functional significance of these regions of orientated remanence is not known, but such a pattern could result from the ordered alignment of per- manently magnetic particles comprising a magnetoreceptor system. INTRODUCTION The magnetic field of the earth influences the orientation of organisms ranging from unicellular algae (Lins de Barros, Esquivel, Danon & De Oliveira, 1981) and bacteria (Blakemore, 1975; Blakemore, Frankel & Kalmijn, 1980) to birds (e.g. -

Disease of Aquatic Organisms 100:89

Vol. 100: 89–93, 2012 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published August 27 doi: 10.3354/dao02510 Dis Aquat Org OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS INTRODUCTION Disease effects on lobster fisheries, ecology, and culture: overview of DAO Special 6 Donald C. Behringer1,2,*, Mark J. Butler IV3, Grant D. Stentiford4 1Program in Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, School of Forest Resources and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32653, USA 2Emerging Pathogens Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 3Department of Biological Sciences, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia 23529, USA 4European Union Reference Laboratory for Crustacean Diseases, Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), Weymouth Laboratory, Weymouth, Dorset DT4 8UB, UK ABSTRACT: Lobsters are prized by commercial and recreational fishermen worldwide, and their populations are therefore buffeted by fishery practices. But lobsters also remain integral members of their benthic communities where predator−prey relationships, competitive interactions, and host−pathogen dynamics push and pull at their population dynamics. Although lobsters have few reported pathogens and parasites relative to other decapod crustaceans, the rise of diseases with consequences for lobster fisheries and aquaculture has spotlighted the importance of disease for lobster biology, population dynamics and ecology. Researchers, managers, and fishers thus increasingly recognize the need to understand lobster pathogens and parasites so they can be managed proactively and their impacts minimized where possible. At the 2011 International Con- ference and Workshop on Lobster Biology and Management a special session on lobster diseases was convened and this special issue of Diseases of Aquatic Organisms highlights those proceed- ings with a suite of articles focused on diseases discussed during that session.