The Jamaican Railway — a Preliminary Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Update on Systems Subsequent to Tropical Storm Grace

Update on Systems subsequent to Tropical Storm Grace KSA NAME AREA SERVED STATUS East Gordon Town Relift Gordon Town and Kintyre JPS Single Phase Up Park Camp Well Up Park Camp, Sections of Vineyard Town Currently down - Investigation pending August Town, Hope Flats, Papine, Gordon Town, Mona Heights, Hope Road, Beverly Hills, Hope Pastures, Ravina, Hope Filter Plant Liguanea, Up Park Camp, Sections of Barbican Road Low Voltage Harbour View, Palisadoes, Port Royal, Seven Miles, Long Mountain Bayshore Power Outage Sections of Jack's Hill Road, Skyline Drive, Mountain Jubba Spring Booster Spring, Scott Level Road, Peter's Log No power due to fallen pipe West Constant Spring, Norbrook, Cherry Gardens, Havendale, Half-Way-Tree, Lady Musgrave, Liguanea, Manor Park, Shortwood, Graham Heights, Aylsham, Allerdyce, Arcadia, White Hall Gardens, Belgrade, Kingswood, Riva Ridge, Eastwood Park Gardens, Hughenden, Stillwell Road, Barbican Road, Russell Heights Constant Spring Road & Low Inflows. Intakes currently being Gardens, Camperdown, Mannings Hill Road, Red Hills cleaned Road, Arlene Gardens, Roehampton, Smokey Vale, Constant Spring Golf Club, Lower Jacks Hill Road, Jacks Hill, Tavistock, Trench Town, Calabar Mews, Zaidie Gardens, State Gardens, Haven Meade Relift, Hydra Drive Constant Spring Filter Plant Relift, Chancery Hall, Norbrook Tank To Forrest Hills Relift, Kirkland Relift, Brentwood Relift.Rock Pond, Red Hills, Brentwood, Leas Flat, Belvedere, Mosquito Valley, Sterling Castle, Forrest Hills, Forrest Hills Brentwood Relift, Kirkland -

History of St. James

History of St. James Named after James, Duke of York, by Sir Thomas Modyford, St. James was among the second batch of parishes to be formed in Jamaica in about 1664-1655; the others in this batch were St. George, St. Mary, St. Ann and St. Elizabeth. At the time of its formation, it was much larger than it now is, as it included what are now the separate parishes of Trelawny and Hanover. For many years after the English conquest, the north side of the island including St. James was sparsely settled and in 1673, only 146 persons resided in the entire parish. It was considered as one of the poorest parishes and in 1711-12, the citizens of St. James were excused from taxation because of its few inhabitants, the lack of towns and its modest commerce. In 1724, the first road Act for the parish was passed - the road going from The Cave in Westmoreland to the west end of St. James and a court of quarter sessions was established four years later. Montego Bay Montego Bay circa 1910 Montego Bay ca.1910 There have been various explanations of how Montego Bay came by its name. Historians agree that the theory with the greatest probability is that the name “montego “was derived from the Spanish word “manteca”, meaning lard or butter; an early map of Jamaica has the Montego Bay area listed as “Bahia de Manteca” or “Lard Bay”. The region now known as Montego Bay had a dense population of wild hogs which the Spanish were said to have slaughtered in large numbers in order to collect hog’s butter (lard) for export to Cartagena. -

We Make It Easier for You to Sell

We Make it Easier For You to Sell Travel Agent Reference Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE ITEM PAGE Accommodations .................. 11-18 Hotels & Facilities .................. 11-18 Air Service – Charter & Scheduled ....... 6-7 Houses of Worship ................... .19 Animals (entry of) ..................... .1 Jamaica Tourist Board Offices . .Back Cover Apartment Accommodations ........... .19 Kingston ............................ .3 Airports............................. .1 Land, History and the People ............ .2 Attractions........................ 20-21 Latitude & Longitude.................. .25 Banking............................. .1 Major Cities......................... 3-5 Car Rental Companies ................. .8 Map............................. 12-13 Charter Air Service ................... 6-7 Marriage, General Information .......... .19 Churches .......................... .19 Medical Facilities ..................... .1 Climate ............................. .1 Meet The People...................... .1 Clothing ............................ .1 Mileage Chart ....................... .25 Communications...................... .1 Montego Bay......................... .3 Computer Access Code ................ 6 Montego Bay Convention Center . .5 Credit Cards ......................... .1 Museums .......................... .24 Cruise Ships ......................... .7 National Symbols .................... .18 Currency............................ .1 Negril .............................. .5 Customs ............................ .1 Ocho -

World Bank Document

37587 Public Disclosure Authorized National and Regional Secondary Level Examinations and the Reform of Secondary Education (ROSE II)1 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared for the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Culture Government of Jamaica January 2003 Public Disclosure Authorized Carol Anne Dwyer Abigail M. Harris and Loretta Anderson 1 This report is based on research conducted by Carol A. Dwyer and Loretta Anderson with funding from the Japan PHRD fund. It extends the earlier investigation to incorporate comments made at the presentation to stake- holders and additional data analyses and synthesis. The authors are grateful for the generous support of the Ministry Public Disclosure Authorized of Education, Youth, and Culture without whose contributions in time and effort this report would not have been possible. Acknowledgement is also given to W. Miles McPeek and Carol-Anne McPeek for their assistance in pre- paring the report. Findings and recommendations presented in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Jamaican government or the World Bank. 2 A Study of Secondary Education in Jamaica Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures 3 Executive Summary 4 Recommendation 1 4 Recommendation 2 5 Introduction and Rationalization 8 Evaluation of the CXC and SSC examinations 10 CXC Examinations. 13 SSC Examinations. 13 CXC & SSC Design & Content Comparison. 13 Vocational and technical examinations. 15 JHSC Examinations. 15 Examinations and the Curriculum. 16 Junior High School and Upper Secondary Curricula. 18 The Impact Of Examinations On Students’ School Performance And Self- Perceptions. 19 Data on Student’s Non-Academic Traits. -

Cok Remittance Services Limited Subagent Locations

COK REMITTANCE SERVICES LIMITED SUBAGENT LOCATIONS Responsible Tel/Fax # Business Hr Pin # Locations Officers (area code 1876) Barrett’s Cambio 16 Burke Street, Spanish Town, St. Carol Barrett Tel: 984-2028 Mon – Sat 01407 Catherine Fax: 984-5384 9:00am – 5pm Tel: 764-1606 Mon – Thur 8:00am- COK Sodality Co-op Tina Livingston Fax: 926-0222 4pm Fridays 00278 66 Slipe Road, Kingston 5 8:00am-3pm COK Sodality Co-op Morris Tel: 764-1639 Mon – Thur 8:00am- Units 9 & 10, Winchester Business Livingston Fax: 926-4631 4pm Fridays 00279 Centre, 15 Hope Road, Kingston 10 8:00am-3pm COK Sodality Co-op Tel: 764-1656 Mon – Fri 9:00am- Shop # 3 McMaster Centre, Oral Sewell Fax: 988-5157 4pm 00280 Portmore, St. Catherine Tel: 764-1687 Mon – Thur 8:00am- COK Sodality Co-op Stanford Fax: 962-0885 4pm Fridays 00773 Units 1, 2 & 8 Mandeville Plaza, Hastings 8:00am-3pm Mandeville, Manchester Tel: 764-1672 Mon – Thur 8:00am- COK Sodality Co-op Fax: 952-1334 4pm Fridays 00425 Roger Shippey 30-34 Market Street, Montego Bay, 8:00am-3pm St. James C & W J Co-op Tel: 986-2287 Mon – Thur 8:30am- C.J. Stuart Building, Main Street, Daliah Royal Fax: 902-4302 3pm Fridays 01156 May Pen, Clarendon 8:30am-4pm Tel/Fax: Mon – Thur 8:30am- C & W J Co-op Carmen Barrett 986-3021 3pm Fridays 01176 Bustamante Drive, Lionel Town 8:30am-4pm Tel/Fax: Mon – Thur 8:30am- Rose-Marie C & W J Co-op 966-8839 3pm Fridays 01155 Lee-Weir Main Street, Kellits, Clarendon 8:30am-4pm Mon & Fri 8:15am- C & W J Co-op Tel: 955-2706 4pm Tues, Wed & 00302 79 Great Georges Street, P.O. -

Destination Jamaica

© Lonely Planet Publications 12 Destination Jamaica Despite its location almost smack in the center of the Caribbean Sea, the island of Jamaica doesn’t blend in easily with the rest of the Caribbean archipelago. To be sure, it boasts the same addictive sun rays, sugary sands and pampered resort-life as most of the other islands, but it is also set apart historically and culturally. Nowhere else in the Caribbean is the connection to Africa as keenly felt. FAST FACTS Kingston was the major nexus in the New World for the barbaric triangular Population: 2,780,200 trade that brought slaves from Africa and carried sugar and rum to Europe, Area: 10,992 sq km and the Maroons (runaways who took to the hills of Cockpit Country and the Blue Mountains) safeguarded many of the African traditions – and Length of coastline: introduced jerk seasoning to Jamaica’s singular cuisine. St Ann’s Bay’s 1022km Marcus Garvey founded the back-to-Africa movement of the 1910s and ’20s; GDP (per head): US$4600 Rastafarianism took up the call a decade later, and reggae furnished the beat Inflation: 5.8% in the 1960s and ’70s. Little wonder many Jamaicans claim a stronger affinity for Africa than for neighboring Caribbean islands. Unemployment: 11.3% And less wonder that today’s visitors will appreciate their trip to Jamaica Average annual rainfall: all the more if they embrace the island’s unique character. In addition to 78in the inherent ‘African-ness’ of its population, Jamaica boasts the world’s Number of orchid species best coffee, world-class reefs for diving, offbeat bush-medicine hiking tours, found only on the island: congenial fishing villages, pristine waterfalls, cosmopolitan cities, wetlands 73 (there are more than harboring endangered crocodiles and manatees, unforgettable sunsets – in 200 overall) short, enough variety to comprise many utterly distinct vacations. -

Community Report Trench Town June 2020

Conducting Baseline Studies for Seventeen Vulnerable and Volatile Communities in support of the Community Renewal Programme Financing Agreement No.: GA 43/JAM Community Report Trench Town June 2020 Submitted by: 4 Altamont Terrace, Suite #1’ Kingston 5, Jamaica W.I. Telephone, 876-616-8040, 876-929-5736, 876- 322- 3227, Email: [email protected] or [email protected] URL: www.Bracconsultants.com 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Sample Size ...................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Demographic Profile of Household Respondents ................................................... 5 2.0. OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................... 6 2.1. Description of Community Boundaries ................................................................... 6 2.2. Estimated Population ............................................................................................ 7 2.3. Housing Characteristics ......................................................................................... 7 2.4. Development Priorities .......................................................................................... 8 3.0. PRESENTATION OF BASELINE DATA ............................................................... 10 3.1. GOVERNANCE ............................................................................................... -

Jamaican Beaches Introduction

Jamaican Beaches Introduction Visiting the beach is a traditional recreational activity for many Jamaicans. With an increasing population, there is a great demand for the use of beaches. However, many of the public beaches are of poor quality, lack proper facilities, and face the problem of fishermen encroaching. Over the years some of these natural resources are on the verge of destruction because of the inadvertent and/or direct intentions of organizations and individuals. One such threat to the preservation of beaches is pollution. To have healthy environmentally friendly beaches in our Island we must unite to prevent pollution. This display gives an overview of some beaches in Jamaica and existing threats. It also examines the Kingston Harbour and how we can protect these natural resources. Jamaica is blessed with many beautiful beaches in the different parishes; the most popular are located in Westmoreland (Negril), St. Ann, St. James, and St. Catherine (Portmore). Some of the more popular beaches in the parishes: Kingston and St. Andrew Harbour Head Gunboat Copacabana Ocean Lake St. Thomas Lyssons Rozelle South Haven Mezzgar’s Run Retreat Prospect Rocky Point Portland Innis Bay Long Bay Boston Winnifred Blue Hole Hope Bay St. Mary Rio Nuevo Rockmore Murdock St. Ann Roxborough Priory Salem Sailor’s Hole Cardiff Hall Discovery Bay Dunn’s River Beach Trelawny Rio Bueno Braco Silver Sands Flamingo Half Moon Bay St. James Greenwood RoseHall Coral Gardens Ironshore Doctor’s Cave Hanover Tryall Lance’s Bay Bull Bay Westmoreland Little Bay Whitehouse Fonthill Bluefield St. Catherine Port Henderson Hellshire Fort Clarence St. Elizabeth Galleon Hodges Fort Charles Calabash Bay Great Bay Manchester Calabash Bay Hudson Bay Canoe Valley Clarendon Barnswell Dale Jackson Bay The following is a brief summary of some of our beautiful beaches: Walter Fletcher Beach Before 1975 it was an open stretch of public beach in Montego Bay with no landscaping and privacy; it was visible from the main road. -

The History of St. Ann

The History of St. Ann Location and Geography The parish of St. Ann is is located on the nothern side of the island and is situated to the West of St. Mary, to the east of Trelawny, and is bodered to the south by both St. Catherine and Clarendon. It covers approximately 1,212 km2 and is Jamaica’s largest parish in terms of land mass. St. Ann is known for its red soil, bauxite - a mineral that is considered to be very essential to Jamaica; the mineral is associated with the underlying dry limestone rocks of the parish. A typical feature of St. Ann is its caves and sinkholes such as Green Grotto Caves, Bat Cave, and Dairy Cave, to name a few. The beginning of St. Ann St. Ann was first named Santa Ana (St. Ann) by the Spaniards and because of its natural beauty, it also become known as the “Garden Parish” of Jamaica. The parish’s history runs deep as it is here that on May 4, 1494 while on his second voyage in the Americas, Christopher Columbus first set foot in Jamaica. It is noted that he was so overwhelmed by the attractiveness of the parish that as he pulled into the port at St. Anns Bay, he named the place Santa Gloria. The spot where he disembarked he named Horshoe Bay, primarily because of the shape of the land. As time went by, this name was changed to Dry Harbour and eventually, a more fitting name based on the events that occurred - Discovery Bay. -

A New Door Opened: a Tracer Study of the Teenage Mothers Project, Jamaica Rolande Degazon-Johnson

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 454 963 PS 029 585 AUTHOR Degazon-Johnson, Roli TITLE A New Door Opened: A Tracer Study of the. Teenage Mothers Project, Jamaica. Early Childhood Development: Practice and Reflections 13. Following Footsteps. INSTITUTION Bernard Van Leer Foundation, The Hague (Netherlands). ISBN ISBN-90-6195-057-0 ISSN ISSN-1382-4813 PUB DATE 2001-06-00 NOTE 124p. AVAILABLE FROM Bernard van Leer Foundation, P.O. Box 82334, 2508 EH, The Hague, Netherlands. Tel: 31-70-3512040; Fax: 31-70-3502373; e-mail: registry @bvleerf.nl; Web site: http://www.bernardvanleer.org. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; *Adolescents; Children; Comparative Analysis; Developing Nations; *Early Parenthood; Employed Parents; Employment Patterns; Ethnography; Followup Studies; Foreign Countries; Intervention; *Mothers; Parent Attitudes; Program Descriptions; *Program Effectiveness; Program Evaluation IDENTIFIERS Jamaica ABSTRACT In the Parish of Clarendon in Jamaica, about 10 percent of infants are born to teenage mothers. Between 1986 and 1996, over 500 young mothers and their children participated in the Teenage Mothers Programme (TMP). The TMP took an approach that encompassed the development of the young women, stimulation and care for the infants, support in the home, and contacts with the infants' fathers. Ten of the mothers who had participated in the early years of the TMP were traced in 1999, and they and their children were interviewed, as were a matched comparison group of another 10 mothers and children who had not been in the program. In addition, a focus group interview was conducted with the 10 TMP participants to gain additional information on the positive features of the TMP and suggestions for improvement. -

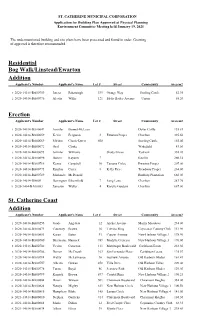

Residential Bog Walk/Linstead/Ewarton Addition Applicant's Number Applicant's Name Lot # Street Community Area M2

ST. CATHERINE MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Application for Building Plan Approved at Physical Planning Environment Committee Meeting held January 19, 2021 The undermentioned building and site plans have been processed and found in order. Granting of approval is therefore recommended. Residential Bog Walk/Linstead/Ewarton Addition Applicant's Number Applicant's Name Lot # Street Community Area m2 1 2020-14014-BA00759 Janeta Paharsingh 399 Orange Way Sterling Castle 52.95 2 2020-14014-BA00776 Aleatia Willis 121 Eddie Bailey Avenue Union 65.20 Erection Applicant's Number Applicant's Name Lot # Street Community Area m2 1 2020-14014-BA00647 Jennifer Bennet-McLean Dover Castle 155.83 2 2020-14014-BA00659 Kevin Ferguson 3 Ewarton Proper Charlton 395.60 3 2020-14014-BA00669 Miriam Clunie-Davis 608 Sterling Castle 165.00 4 2020-14014-BA00672 Oral Clarke Wakefield 83.60 5 2020-14014-BA00695 Jennifer Williams Shady Grove Tydixon 338.20 6 2020-14014-BA00696 Barton Kayann 7 Knollis 260.14 7 2020-14014-BA00716 Kemar Campbell 10 Tamana Cirlce Ewarton Proper 207.00 8 2020-14014-BA00775 Rynthia Carter 8 Kelly Piece Treadway Proper 264.00 9 2020-14014-BA00789 Marlando McDonald Banbury Plantation 660.00 10 2020-14014-BA609 Barrington Bloomfield 7 Long Lane Charlton 283.76 11 2020-1404-BA00683 Jameson Waller 4 Roselle Gardens Charlton 667.00 St. Catherine Coast Addition Applicant's Number Applicant's Name Lot # Street Community Area m2 1 2020-14014-BA00255 Gayle Angeleta 12 Archer Avenue Morris Meadows 234.00 2 2020-14014-BA00475 Courtney Brown 16 Trevino Ring -

Letter Post Compendium Jamaica

Letter Post Compendium Jamaica Currency : Dollar Jamaïquain Basic services Mail classification system (Conv., art. 17.4; Regs., art. 17-101) 1 Based on speed of treatment of items (Regs., art. 17-101.2: Yes 1.1 Priority and non-priority items may weigh up to 5 kilogrammes. Whether admitted or not: Yes 2 Based on contents of items: Yes 2.1 Letters and small packets weighing up to 5 kilogrammes (Regs., art. 17-103.2.1). Whether admitted or not Yes (dispatch and receipt): 2.2 Printed papers weighing up to 5 kilogrammes (Regs., art. 17-103.2.2). Whether admitted or not for Yes dispatch (obligatory for receipt): 3 Classification of post items to the letters according to their size (Conv., art. 17,art. 17-102.2) - Optional supplementary services 4 Insured items (Conv., art. 18.2.1; Regs., 18-001.1) 4.1 Whether admitted or not (dispatch and receipt): No 4.2 Whether admitted or not (receipt only): No 4.3 Declaration of value. Maximum sum 4.3.1 surface routes: SDR 4.3.2 air routes: SDR 4.3.3 Labels. CN 06 label or two labels (CN 04 and pink "Valeur déclarée" (insured) label) used: - 4.4 Offices participating in the service: - 4.5 Services used: 4.5.1 air services (IATA airline code): 4.5.2 sea services (names of shipping companies): 4.6 Office of exchange to which a duplicate CN 24 formal report must be sent (Regs., art.17-138.11): Office Name : Office Code : Address : Phone : Fax : E-mail 1 : E-mail 2: 5 Cash-on-delivery (COD) items (Conv., art.