HISTORY of EUROPE and WORLD 1760 AD to 1871 AD Directorate Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noise and Silence in Rigoletto's Venice

Cambridge Opera Journal, 31, 2-3, 188–210 © The Author(s), 2020. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://cre ativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0954586720000038 Noise and Silence in Rigoletto’s Venice ALESSANDRA JONES* Abstract: In this article I explore how public acts of defiant silence can work as forms of his- torical evidence, and how such refusals constitute a distinct mode of audio-visual attention and political resistance. After the Austrians reconquered Venice in August 1849, multiple observers reported that Venetians protested their renewed subjugation via theatre boycotts (both formal and informal) and a refusal to participate in festive occasions. The ostentatious public silences that met the daily Austrian military band concerts in the city’s central piazza became a ritual that encouraged foreign observers to empathise with the Venetians’ plight. Whereas the gondolier’s song seemed to travel separate from the gondolier himself, the piazza’s design instead encour- aged a communal listening coloured by the politics of the local cafes. In the central section of the article, I explore the ramifications of silence, resistance and disconnections between sight and sound as they shape Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, which premiered at Venice’s Teatro la Fenice in 1851. The scenes in Rigoletto most appreciated by the first Venetian audiences hinge on the power to observe and overhear, suggesting that early spectators experienced the opera through a mode of engagement born of the local material conditions and political circumstances. -

© 2013 Yi-Ling Lin

© 2013 Yi-ling Lin CULTURAL ENGAGEMENT IN MISSIONARY CHINA: AMERICAN MISSIONARY NOVELS 1880-1930 BY YI-LING LIN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral committee: Professor Waïl S. Hassan, Chair Professor Emeritus Leon Chai, Director of Research Professor Emeritus Michael Palencia-Roth Associate Professor Robert Tierney Associate Professor Gar y G. Xu Associate Professor Rania Huntington, University of Wisconsin at Madison Abstract From a comparative standpoint, the American Protestant missionary enterprise in China was built on a paradox in cross-cultural encounters. In order to convert the Chinese—whose religion they rejected—American missionaries adopted strategies of assimilation (e.g. learning Chinese and associating with the Chinese) to facilitate their work. My dissertation explores how American Protestant missionaries negotiated the rejection-assimilation paradox involved in their missionary work and forged a cultural identification with China in their English novels set in China between the late Qing and 1930. I argue that the missionaries’ novelistic expression of that identification was influenced by many factors: their targeted audience, their motives, their work, and their perceptions of the missionary enterprise, cultural difference, and their own missionary identity. Hence, missionary novels may not necessarily be about conversion, the missionaries’ primary objective but one that suggests their resistance to Chinese culture, or at least its religion. Instead, the missionary novels I study culminate in a non-conversion theme that problematizes the possibility of cultural assimilation and identification over ineradicable racial and cultural differences. -

Locating the Wallachian Revolution of *

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./SX LOCATING THE WALLACHIAN REVOLUTION OF * JAMES MORRIS Emmanuel College, Cambridge ABSTRACT. This article offers a new interpretation of the Wallachian revolution of . It places the revolution in its imperial and European contexts and suggests that the course of the revolution cannot be understood without reference to these spheres. The predominantly agrarian principality faced different but commensurate problems to other European states that experienced revolution in . Revolutionary leaders attempted to create a popular political culture in which all citizens, both urban and rural, could participate. This revolutionary community formed the basis of the gov- ernment’s attempts to enter into relations with its Ottoman suzerain and its Russian protector. Far from attempting to subvert the geopolitical order, this article argues that the Wallachians positioned themselves as loyal subjects of the sultan and saw their revolution as a meeting point between the Ottoman Empire and European civilization. The revolution was not a staging post on the road to Romanian unification, but a brief moment when it seemed possible to realize internal regeneration on a European model within an Ottoman imperial framework. But the Europe of was too unstable for the revolutionaries to succeed. The passing of this moment would lead some to lose faith in both the Ottoman Empire and Europe. -

1848 Revolutions Special Subject I READING LIST Professor Chris Clark

1848 Revolutions Special Subject I READING LIST Professor Chris Clark The Course consists of 8 lectures, 16 presentation-led seminars and 4 gobbets classes GENERAL READING Jonathan Sperber, The European Revolutions, 1848-1851 (Cambridge, 1994) Dieter Dowe et al., eds., Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform (Oxford, 2001) Priscilla Smith Robertson, The Revolutions of 1848, a social history (Princeton, 1952) Michael Rapport, 1848: Year of Revolution (London, 2009) SOCIAL CONFLICT BEFORE 1848 (i) The ‘Galician Slaughter’ of 1846 Hans Henning Hahn, ‘The Polish Nation in the Revolution of 1846-49’, in Dieter Dowe et al., eds., Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform, pp. 170-185 Larry Wolff, The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture (Stanford, 2010), esp. chapters 3 & 4 Thomas W. Simons Jr., ‘The Peasant Revolt of 1846 in Galicia: Recent Polish Historiography’, Slavic Review, 30 (December 1971) pp. 795–815 (ii) Weavers in Revolt Robert J. Bezucha, The Lyon Uprising of 1834: Social and Political Conflict in the Early July Monarchy (Cambridge Mass., 1974) Christina von Hodenberg, Aufstand der Weber. Die Revolte von 1844 und ihr Aufstieg zum Mythos (Bonn, 1997) *Lutz Kroneberg and Rolf Schloesser (eds.), Weber-Revolte 1844 : der schlesische Weberaufstand im Spiegel der zeitgenössischen Publizistik und Literatur (Cologne, 1979) Parallels: David Montgomery, ‘The Shuttle and the Cross: Weavers and Artisans in the Kensington Riots of 1844’ Journal of Social History, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Summer, 1972), pp. 411-446 (iii) Food riots Manfred Gailus, ‘Food Riots in Germany in the Late 1840s’, Past & Present, No. 145 (Nov., 1994), pp. 157-193 Raj Patel and Philip McMichael, ‘A Political Economy of the Food Riot’ Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 32/1 (2009), pp. -

From the Euphrates to the Thames and The

Symposium From the Euphrates to the Thames and the Mur 200 years of Middle Eastern Studies and Middle Eastern Collections 10 and 11 November 2011 Austrian Cultural Forum London A two day conference at the Austrian Cultural Forum London celebrating the 200 th anniversary of the founding of the Museum Joanneum in Graz Organisers: Austrian Cultural Forum London Universalmuseum Joanneum Graz Institut für Iranistik, Akademie der Wissenschaften Karl Franzens Universität Graz Urania Graz Sponsor: Styrian Chamber of Commerce Programme 10 November 2011 10am Welcome Peter Mikl, Director, Austrian Cultural Forum London The Archduke, The Museum Joanneum and the University 10.30am Gerhard M. Dienes, Universalmuseum Joanneum Josef Herk, President, Styrian Chamber of Commerce Archduke John of Austria (1782-1859), an innovative-minded Habsburg Prince 11am Coffee break 11.15am Wolfgang Muchitsch, Director Universalmuseum Joanneum The Joanneum, Austria‘s Universalmuseum 11.45am Helmut Konrad, Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Karl Franzens-Universität Graz The Graz University – bulwark and bridge to the southeast 12.15pm Lunch break From Graz to the Orient, from the Orient to Graz 2pm Karl Peitler, Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz Anton Prokesch-Osten and his donations to the Joanneum 2.45pm Heinz Trenczak, Graz Film presentation: „Djavidan - Queen for a Day”by Heinz Trenczak and Arthur Summereder 3.30pm Coffee break Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, Influential Literary Translator 4pm Hammer-Purgstall’s translations from Persian Nima Mina, SOAS, University of London 4.30pm Gerhard M. Dienes, Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, Hafez and Goethe 5pm End Evening Concert 7pm West-East Divan Liederabend Goethe-Lieder von Franz Schubert and Hugo Wolf Jennifer France, Soprano Katie Bray, Mezzo-soprano Gareth John, Baritone Sanaz Sotoudeh, Piano 11 November 2011 Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall and James Claudius Rich: The Dawn of Middle Eastern Studies in Austria and England 10am Hannes D. -

Mitteilungen Für Die Presse

Read the speech online: www.bundespraesident.de Page 1 of 6 Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier at the inauguration of the Robert-Blum-Saal with artworks depicting Germany’s history of democracy at Schloss Bellevue on 9 November 2020 According to legend, the last words of Robert Blum were “I die for freedom, may my country remember me.” He was executed – shot – by imperial military forces on 9 November 1848, one day before his 41st birthday. The German democrat and champion for freedom, one of the most well-known members of the Frankfurt National Assembly, thus died on a heap of sand in Brigittenau, a Viennese suburb. The bullets ended the life of a man who had fought tirelessly for a Germany unified in justice and in freedom – as a political publicist, publisher and founder of the Schillerverein in Leipzig, as a parliamentarian in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt, and finally with a gun in his hand on the barricades in Vienna. To the very last, Robert Blum fought for a German nation-state in the republican mould, legitimised by parliamentary structures. He campaigned for a brand of democracy in which civil liberties and human rights were accorded to one and all. And he fought for a Europe in which free peoples should live together in peace, from France to Poland and to Hungary. His death on 9 November 1848 marked one of the many turning points in our history. By executing the parliamentarian Robert Blum, the princes and military commanders of the Ancien Régime demonstrated their power and sent an unequivocal message to the Paulskirche National Assembly. -

Use of Theses

Australian National University THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. UEKIEMORI AND THE USE OF HISTORY A sub-thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of East Asian Studies in the Australian National University By Loh Kwok Cheong Asian History Centre Australian National University November 1994 To Pei Ling Affirmation This thesis is the sole work of the author, Loh Kwok Cheong, and except where due acknowledgement is made in the text, does not, to the best of my knowledge, contain material previously presented, published or written by another person. ii Acknowledgement I wish to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. John Caiger, for showing me the way to discovering my interest and for his encouragement, advice and support throughout the writing of this study. I would also like to thank Dr. Tessa Morris-Suzuki for her comments and support. Special thanks also goes to members of the Faculty of Asian Studies and Division of Asian and Pacific History, RSPacS for their assistance and patience. Finally, my deepest gratitude is for my wife, Pei Ling, who has been most supportive and tolerant of my temperaments since I embarked on this course. iii Abstract German historian Michael Sturmer ascribes a functional role for historical consciousness: "in a country without history, he who fills the memory, defines the concepts and interprets the past, wins the future."1 Although Sturmer was concerned with the way in which understanding of history shapes contemporary discourse in post World War Two Germany, his statement also aptly described the manner in which history has been used in Japan since the advent of the modem century. -

Quadrilatero

CPIA 1 FOGGIA In copertina: Eugène Delacroix, La libertà che guida il popolo ,1831 Il decennio francese La Rivoluzione francese e l’età napoleonica trasformarono profondamente l’Europa. Sul piano sociale furono eliminati in gran parte dell’Europa i privilegi della nobiltà e del clero; sul piano politico fu abbattuta la monarchia assoluta; sul piano territoriale Napoleone modificò i confini fra gli Stati; sul piano ideologico si affermarono i nuovi ideali di libertà, uguaglianza e fraternità. La marcia delle truppe francesi, guidate dal giovane Bonaparte fu inarrestabile. J. L. David, Napoleone attraversa le Alpi CPIA 1 FOGGIA L’Italia napoleonica Le vittorie di Napoleone sconvolsero l’ordine dell’ Europa ed anche degli Stati italiani. Nel marzo 1796 l’esercito valicò le Alpi e in poco tempo tutta l’Italia del Nord veniva conquistata. I sovrani dei vari stati fuggirono e sotto la protezione delle truppe napoleoniche furono create le repubbliche sorelle della Francia: nel 1797 la Repubblica Cisalpina con capitale Milano e la Repubblica Ligure con capitale Genova; nel 1798 le forze francesi cacciarono il papa da Roma e crearono la Repubblica Romana; nel 1799 il sovrano del regno di Napoli fuggì incalzato dall’esercito francese e nacque la Repubblica Partenopea. L’Italia era ormai un dominio francese, uniche eccezioni il Veneto, che col trattato di Campoformio veniva ceduto all’Austria e la Sicilia e la Sardegna ancora in mano ai Borbone. Fatta eccezione per una breve interruzione la dominazione francese durò quasi un decennio, durante cui l’Italia conobbe un’età di progresso economico e di modernizzazione amministrativa. CPIA 1 FOGGIA Il congresso di Vienna Nell’ottobre 1813 a Lipsia (nell’attuale Germania) una coalizione formata da Austria, Russia, Inghilterra e Prussia sconfisse Napoleone Bonaparte e lo costrinse a firmare la rinuncia al trono francese e ad andare in esilio nell’isola d’Elba. -

A Short History of Russia (To About 1970)

A Short History of Russia (to about 1970) Foreword. ...............................................................................3 Chapter 1. Early History of the Slavs, 2,000 BC - AD 800. ..........4 Chapter 2. The Vikings in Russia.............................................6 Chapter 3. The Adoption of Greek Christianity: The Era of Kievan Civilisation. ..........................................................7 Chapter 4. The Tatars: The Golden Horde: The Rise of Moscow: Ivan the Great. .....................................................9 Chapter 5. The Cossacks: The Ukraine: Siberia. ...................... 11 Chapter 6. The 16th and 17th Centuries: Ivan the Terrible: The Romanoffs: Wars with Poland. .............................. 13 Chapter 7. Westernisation: Peter the Great: Elizabeth.............. 15 Chapter 8. Catherine the Great............................................. 17 Chapter 9. Foreign Affairs in the 18th Century: The Partition of Poland. .............................................................. 18 Chapter 10. The Napoleonic Wars. .......................................... 20 Chapter 11. The First Part of the 19th Century: Serfdom and Autocracy: Turkey and Britain: The Crimean War: The Polish Rebellion................................................... 22 Chapter 12. The Reforms of Alexander II: Political Movements: Marxism. ........................................................... 25 Chapter 13. Asia and the Far East (the 19th Century) ................ 28 Chapter 14. Pan-Slavism....................................................... -

French Thought and the American Military Mind:A History Of

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 French Thought and the American Military Mind: A History of French Influence on the American Way of Warfare from 1814 Through 1941 Michael A. Bonura Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES FRENCH THOUGHT AND THE AMERICAN MILITARY MIND: A HISTORY OF FRENCH INFLUENCE ON THE AMERICAN WAY OF WARFARE FROM 1814 THROUGH 1941 BY MICHAEL ANDREW BONURA A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester 2008 Copyright © 2008 Michael Andrew Bonura All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Michael Andrew Bonura defended on August 6, 2008. ____________________________ Frederick R. Davis Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________ J. Anthony Stallins Outside Committee Member ____________________________ James P. Jones Committee Member ____________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member ____________________________ Darrin M. McMahon Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As everyone knows, a project of this size is the product of more than a single person, and many have helped me along the way. First and foremost I would like to thank Dr. Frederick R. Davis, my major professor, who agreed to take me on as a student after the retirement of Dr. Donald Horward. Dr. Davis took an early interest in my development as a Historian and continued to encourage my work and study in the Historian’s craft, even by letting me audit his Historical Methods course. -

"The Greeks in the History of the Black Sea" Report

DGIV/EDU/HIST (2000) 01 Activities for the Development and Consolidation of Democratic Stability (ADACS) Meeting of Experts on "The Greeks in the History of the Black Sea" Thessaloniki, Greece, 2-4December 1999 Report Strasbourg Meeting of Experts on "The Greeks in the History of the Black Sea" Thessaloniki, Greece, 2-4December 1999 Report The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................... 5 Introductory remarks by James WIMBERLEY, Head of the Technical Cooperation and Assistance Section, Directorate of Education and Higher Education.................................................................................................................... 6 PRESENTATIONS -Dr Zofia Halina ARCHIBALD........................................................................11 -Dr Emmanuele CURTI ....................................................................................14 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Dr Constantinos CHATZOPOULOS..........................................................................17 APPENDIX I LIST OF PARTICIPANTS.........................................................................................21 APPENDIX II PROGRAMME OF THE SEMINAR.........................................................................26 APPENDIX III INTRODUCTORY PRESENTATION BY PROFESSOR ARTEMIS XANTHOPOULOU-KYRIAKOU.............................................................................30 -

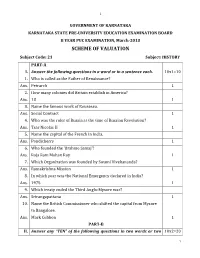

SCHEME of VALUATION Subject Code: 21 Subject: HISTORY PART-A I

1 GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA KARNATAKA STATE PRE-UNIVERSITY EDUCATION EXAMINATION BOARD II YEAR PUC EXAMINATION, March-2013 SCHEME OF VALUATION Subject Code: 21 Subject: HISTORY PART-A I. Answer the following questions in a word or in a sentence each. 10x1=10 1. Who is called as the Father of Renaissance? Ans. Petrarch 1 2. How many colonies did Britain establish in America? Ans. 13 1 3. Name the famous work of Rousseau. Ans. Social Contract 1 4. Who was the ruler of Russia at the time of Russian Revolution? Ans. Tsar Nicolas II 1 5. Name the capital of the French in India. Ans. Pondicherry 1 6. Who founded the ‘Brahmo Samaj’? Ans. Raja Ram Mohan Roy 1 7. Which Organization was founded by Swami Vivekananda? Ans. Ramakrishna Mission 1 8. In which year was the National Emergency declared in India? Ans. 1975 1 9. Which treaty ended the Third Anglo-Mysore war? Ans. Srirangapattana 1 10. Name the British Commissioner who shifted the capital from Mysore to Bangalore. Ans. Mark Cubbon 1 PART-B II. Answer any “TEN” of the following questions in two words or two 10x2=20 1 2 sentences each: 11. Who circumnavigated the earth for the first time? Which country did he belong to? Ans. Ferdinand Magellan– Portugal / Spain 1+1 12. Mention the three important watchwords of French Revolution. Ans. Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. 1+1 13. Name the architect of German Unification. Which policy did he follow? Ans. Bismark – Blood & Iron. 1+1 14. What Is ‘Great Leap Forward’? Who introduced it? Ans.