Lower Warren River Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

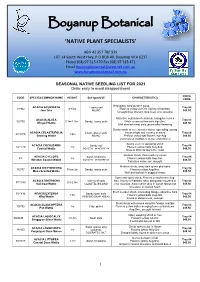

NATIVE SEEDLING LIST for 2021 Order Early to Avoid Disappointment

Boyanup Botanical ‘NATIVE PLANT SPECIALISTS’ ABN 42 357 780 939 LOT 14 South West Hwy, P.O BOX 40, Boyanup W.A 6237 Phone (08) 97 315 470 Fax (08) 97 315 471 Email [email protected] .au www.boyanupbotanical.com.au SEASONAL NATIVE SEEDLING LIST FOR 2021 Order early to avoid disappointment PRICE CODE SPECIES/COMMON NAME HEIGHT Soil type/USE CHARACTERISTICS CODE Host plant, hard durable wood. ACACIA ACUMINATA Tray 64 1/1962 6-10m Loamy soil Flowers yellow Jul-Oct. Variety of habitats. Jam Tree INLAND $49.50 Drought/frost tolerant, long lived, slow growing Attractive multi branched shrub, triangular leaves ACACIA ALATA Tray 64 32/790 0.3m-1.5m Sandy, loamy soils White cream-yellow balls Apr-Dec. Winged Wattle $49.50 Well drained moist soils, prune after flowering Bushy shrub or tree, slender stems, spreading, young ACACIA CELASTRIFOLIA leaves bright red, sweetly scented Tray 64 47/2975 1-3m Loam, gravel soils Glowing Wattle INLAND Profuse yellow ball flowers Apr-Aug $49.50 Common on roadsides, dense understorey Bushy erect to sprawling shrub ACACIA COCHLEARIS Tray 64 24/1220 2m Sandy soil Flowers yellow balls Aug-Sep. Coastal Wattle COASTAL, WINDBREAK $49.50 Grow in thickets along the coast Medium shrub, thick leathery leaves ACACIA CYCLOPS Tray 64 5/8 3m Sand, limestone Flowers yellow balls Sep-Jan. Western Coastal Wattle COASTAL, WINDBREAK $49.50 Tolerates saline soil, drought Medium shrub, wavy dark green phyllodes ACACIA DICTYONEURA Tray 64 35/787 50cm-2m Sandy, loamy soils Flowers yellow Aug-Nov. Musa Scented Wattle $49.50 Well drained soil in dappled shade Open and spiny shrub. -

Evergreen Trees Agonis Flexuosa

Evergreen Trees Agonis flexuosa – Peppermint Willow Graceful willow-like evergreen tree (but without the willows voracious root system) with reddish-brown, deeply furrowed bark to 25’-30’. New leaves and twigs have an attractive reddish cast; clustered small white flowers and brownish fruits are not particularly ornamental. Casaurina stricta – Beefwood Pendulous gray branches; resembles a pine somewhat; tolerates drought, heat, wind, fog. Growth to 20’- 30’. Cinnamomum camphora - Camphor Evergreen trees to 40 feet, with 20-foot spread.. In winter foliage is a shiny yellow green. In early spring new foliage may be pink, red or bronze, depending on tree. Unusually strong structure. Clusters of tiny, fragrant yellow flowers in profusion in May. Geijera parviflora- Australian Willow Evergreen trees with graceful, fine-textured leaves, to 30 feet, 20 feet wide. Main branches weep up and out; little branches hang down. Much of the grace of a willow, much of the toughness of eucalyptus, moderate growth and deep non-invasive roots. Laurus nobilis – Grecian Laurel Slow growth 12-40’. Natural habit is compact, broad-based, often multi-stemmed, gradually tapering cone. Leaves lethery, aromatic. Clusters of small yellow flowers followed by black or purple berries. Magnolia Grandiflora – ‘Little Gem’- Dwarf Southern Magnolia Small tree to 20’ in height. Showy white flowers in the summer. Green glossy leaves. Maytenous boaria - Mayten Evergreen tree with slow to moderate growth to an eventual 30-50 feet, with a 15-foot spread, with long and pendulous branchlets hanging down from branches, giving tree a graceful look. Habit and leaves somewhat like a small scale weeping willow. -

Newsletter No. 271 – February 2012

Newsletter No. 271 – February 2012 FEBRUARY BBQ Saturday 18th naming (although in fairness to Mueller, he was keen to encourage local people to collect and send him Arthur and Linda have kindly made their home plant specimens and rewarded the diligent ones by available for our Welcome to 2012 BBQ, on Saturday naming plants after them). 18th February. The address, for new members, is ‘Wirrawilla’, 40 Lovely Banks Road, Lovely Banks. Bauera This is a small genus of three eastern Please arrive about 5.30 pm. Australian plants, seemingly not as popular as they once were. They are spreading shrubs, preferring PLEASE NOTE THE CORRECTION TO DECEMBER dappled shade and moist rather than a dry situation, INFORMATION. THIS BBQ IS BYO EVERYTHING. PLEASE and are spectacular in flower, usually pink to purple, BRING A SALAD OR DESSERT TO SHARE, BUT EVERYTHING occasionally white. Two of the best known are B. ELSE IS BYO. rubioides (found from Queensland to South Australia) and B. sessiliflora, endemic to the Grampians. They Contact Linda on 52761343 to confirm what you are are named after the Austrian botanical artists bringing, so we don’t end up with 63 desserts and no Ferdinand and Francis Bauer. Ferdinand is considered salads. one of the finest botanical (probably more correctly Being February the weather may be very hot, so biological) artists ever and I have included one of his bring your bathers. But, be warned … Arthur has a paintings here as I have been unable to locate a video camera, and he’s prepared to use it! If the picture of him. -

Identification of Myrtle Rust (Uredo Rangelii)

Identification of Myrtle Rust (Uredo rangelii) 6 October 2010 Hosts Myrtle Rust has been found on the NSW Central Coast on eleven species of cultivated native plants: • Agonis flexuosa (willow myrtle) cv. 'Afterdark' and cv. 'Burgundy' • Tristania neriifolia (water gum) • Syncarpia glomulifera (turpentine) • Callistemon viminalis (bottle brush) • Leptospermum rotundifolium (tea tree) • Syzygium leumannii x Syzygium wilsonii (lilly pilly) • Syzygium jambos (rose apple) • Syzygium australe cv. 'Meridian Midget' • Metrosideros collina cv. Dwarf • Austromyrtus inophloia cv. 'Aurora' and 'Blushing Beauty' (renamed to Gossia inophloia) • Rhodamnia rubescens (scrub turpentine) Other known hosts include Myrtus communis (common myrtle). At present, severe infestation has only been observed on A. flexuosa (willow myrtle) cv. 'Afterdark', Tristania neriifolia (water gum) and Austromyrtus inophloia cv. 'Aurora' and 'Blushing Beauty'. Spread Rust spores travel very long distances on the wind and may infect stands of susceptible plants many kilometres from the original infestation. Rust spores are also gathered and spread by bees. These are natural means of spread that are difficult to control. Humans can also easily spread Myrtle Rust in infested plant material including cut flowers and nursery stock, on clothing and dirty equipment including containers and pruning shears, and on contaminated timber products. Always practise good hygiene when working with native plants and general nursery stock. Images See the following pages. Reporting To report suspect cases of Myrtle Rust, please call the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881. © State of New South Wales through Department of Industry and Investment (Industry & Investment NSW) 2010. You may copy, distribute and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose, provided that you attribute Industry & Investment NSW as the owner. -

Potential Agroforestry Species and Regional Industries for Lower Rainfall

PotentialPotential agroforestryagroforestry speciesspecies andand regionalregional industriesindustries forfor lowerlower rainfall rainfall southernsouthern AustraliaAustralia FLORASEARCHFLORASEARCH 2 2 Australia Australia Potential agroforestry species and regional industries for lower rainfall southern Australia FLORASEARCH 2 Australia A report for the RIRDC / L&WA / FWPA / MDBC Joint Venture Agroforestry Program Future Farm Industries CRC by Trevor J. Hobbs, Mike Bennell, Dan Huxtable, John Bartle, Craig Neumann, Nic George, Wayne O’Sullivan and David McKenna January 2009 © 20092008 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 1 74151 479 7 ISSN 1440-6845 Please cite this report as: Hobbs TJ, Bennell M, Huxtable D, Bartle J, Neumann C, George N, O’Sullivan W and McKenna D (2008). Potential agroforestry species and regional industries for lower rainfall southern Australia: FloraSearch 2. Report to the Joint Venture Agroforestry Program (JVAP) and the Future Farm Industries CRC*. Published by RIRDC, Canberra Publication No. 07/082 Project No. UWA-83A The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia -

Peppermint Tree Scientific Name: Agonis Flexuosa

Peppermint Tree Scientific name: Agonis flexuosa Aboriginal name: Wonnil (Noongar) Plant habit Bark Flower bud Flower About ... Family MYRTACEAE Also called the ‘Willow Myrtle’, this species is native to Climate Temperate the south-west of Western Australia. Habitat Coastal and bushland areas close to the This species is highly adaptable to a range of climates coast and lower Swan Estuary in sandy/ and soils. Because of this, it is often planted along limestone soils verges and in parkland areas. It is a common street tree in many Perth suburbs including Peppermint Form Tree Grove which is named after the tree. Fibrous, rough grey bark Its flowers look similar to the native tea tree. Large, gnarled trunk Peppermint Trees are named after the peppermint Height: 10 – 15 m odour of the leaves when crushed. Width: 6 m Mature trees provide hollows that are used by birds Foliage Weeping foliage and possums for nesting. Mid-to-bright green Long, slender leaves Evergreen Flower Kambarang to Bunuru (Spring and Summer) Aboriginal Uses Sprays of several small white flowers • Leaves were used for smoking and healing Width: 1 cm Flowers have five petals • Oil used to rub on cuts and sores Insect attracting ALGAE BUSTER Developed by SERCUL for use with the Bush Tucker Education Program. Used as food Used as medicine Used as resources Local to SW WA Caution: Do not prepare bush tucker food without having been shown by Indigenous or experienced persons. PHOSPHORUS www.sercul.org.au/our-projects/ AWARENESS PROJECT bushtucker/ Some bush tucker if eaten in large quantities or not prepared correctly can cause illness.. -

Guava (Eucalyptus) Rust Puccinia Psidii

INDUSTRY BIOSECURITY PLAN FOR THE NURSERY & GARDEN INDUSTRY Threat Specific Contingency Plan Guava (eucalyptus) rust Puccinia psidii Plant Health Australia March 2009 Disclaimer The scientific and technical content of this document is current to the date published and all efforts were made to obtain relevant and published information on the pest. New information will be included as it becomes available, or when the document is reviewed. The material contained in this publication is produced for general information only. It is not intended as professional advice on any particular matter. No person should act or fail to act on the basis of any material contained in this publication without first obtaining specific, independent professional advice. Plant Health Australia and all persons acting for Plant Health Australia in preparing this publication, expressly disclaim all and any liability to any persons in respect of anything done by any such person in reliance, whether in whole or in part, on this publication. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of Plant Health Australia. Further information For further information regarding this contingency plan, contact Plant Health Australia through the details below. Address: Suite 5, FECCA House 4 Phipps Close DEAKIN ACT 2600 Phone: +61 2 6215 7700 Fax: +61 2 6260 4321 Email: [email protected] Website: www.planthealthaustralia.com.au PHA & NGIA | Contingency Plan – Guava rust (Puccinia psidii) 1 Purpose and background of this contingency plan ............................................................. -

Appendix 3 Vertebrate Fauna Assessment

A VERTEBRATE FAUNA ASSESSMENT OF THE CLOVERDALE MINERAL SANDS SURVEY AREA Prepared for Iluka Resources Ltd By Ninox Wildlife Consulting February 2006 i Executive Summary The Cloverdale Mineral Sands Project Area is situated approximately 8 km south of Capel, Western Australia. For this fauna assessment, a wider area was surveyed in order to encompass all of the fauna habitats that could be impacted directly or indirectly by the Project. The area assessed for fauna has been called the Survey Area throughout this report. Much of the Survey Area is located on private property on the Southern Swan Coastal Plain (SSCP), although there is a small area of Vacant Crown Land on the Ludlow River. Much of the area is cleared for agriculture with vegetated road reserves, isolated trees in paddocks and small areas of remnant vegetation, some of which has been fenced from stock grazing. A field assessment of the Project Area and surrounds (Survey Area) was carried out over two days in March 2005 by GHD with additional field work conducted by Ninox Wildlife Consulting in mid October 2005. This assessment incorporated a detailed literature review which included a search of State and Commonwealth vertebrate fauna databases, a review of published literature on the vertebrate fauna of the general area and a review of unpublished records from the general area held by Ninox Wildlife Consulting. A total of 46 species of bird has been recorded within the Survey Area. The results of the literature review showed that a further 78 species could be expected to occur as resident, nomadic, migratory or occasional visitors to the general area. -

Anniversary Adventure April 2015

n 9 Pear-fruited Mallee, Eucalyptus pyriformis. A Tour of Trees. 10 Mottlecah, Eucalyptus macrocarpa. Dive into the Western Australian Botanic Garden on an Anniversary Adventure and 11 Rose Mallee, discover its best kept secrets. Eucalyptus rhodantha. 1 Silver Princess, 12 Marri, Explore a special area of the Western Eucalyptus caesia. Australian Botanic Garden with us each Corymbia calophylla. month as we celebrate its 50th anniversary 2 Kingsmill’s Mallee, 13 Western Australian Christmas Tree, in 2015. Eucalyptus kingsmillii. Nuytsia floribunda. In April, we take a winding tour through the 3 Large-fruited Mallee, 14 Dwellingup Mallee, botanic garden to see the most distinctive, Eucalyptus youngiana. Eucalyptus drummondii x rudis rare and special trees scattered throughout its 4 Boab – Gija Jumulu*, (formerly Eucalyptus graniticola). 17 hectares. Adansonia gregorii. 15 Scar Tree – Tuart, 5 Variegated Peppermint, Eucalyptus gomphocephala. Agonis flexuosa. 16 Ramel’s Mallee, 6 Tuart, Eucalyptus rameliana. Eucalyptus gomphocephala. 17 Salmon White Gum, 7 Karri, Eucalyptus lane-poolei. Eucalyptus diversicolor. 18 Red-capped Gum or Illyarrie, 8 Queensland Bottle Tree, Eucalyptus erythrocorys. Brachychiton rupestris. * This Boab, now a permanent resident in Kings Park, was a gift to Western Australia from the Gija people of the East Kimberley. Jumulu is the Gija term for Boab. A Tour of Trees. This month, we take a winding tour through Descend the Acacia Steps to reach the Water Garden the Western Australian Botanic Garden to see where you will find a grove of Dwellingup Mallee the most distinctive, rare and special trees (Eucalyptus drummondii x rudis – formerly Eucalyptus granticola). After discovering a single tree in the wild, scattered throughout its 17 hectares. -

Wellington National Park, Westralia Conservation Park and Wellington Discovery Forest

WELLINGTON NATIONAL PARK, WESTRALIA CONSERVATION PARK AND WELLINGTON DISCOVERY FOREST Management Plan 2008 Department of Environment and Conservation Conservation Commission of Western Australia VISION Over the life of the plan, a balance will exist between the conservation of the planning areas’ natural values and the public demand for recreation and water supply. The area will make an important contribution to reservation of the Jarrah Forest, where natural values, such as granite outcrops, mature growth forest, ecosystems of the Collie River, and our knowledge of them, will be maintained and enhanced for future generations. Visitors to the area will enjoy a range of sustainable recreation opportunities in a variety of forest settings, and provide a benefit to the regional economy. The community will regard the area as a natural asset and will have a greater understanding of its values, and support for their management, through the Wellington Discovery Forest and other education and interpretive facilities. The ancient landscape of the Collie River valley will be recognised as a forest environment of great visual aesthetic appeal, and for its rich Aboriginal heritage, which will be kept alive through the active and ongoing involvement of local Aboriginal people. ii PREFACE The Department of Environment and Conservation (the Department) manages reserves vested in the Conservation Commission of Western Australia (Conservation Commission) and prepares management plans on their behalf. The Conservation Commission issues draft management plans for public comment and provides proposed (final) management plans for approval by the Minister for the Environment. The Conservation and Land Management Act 1984 (the ‘CALM Act’) specifies that management plans must contain: a) a statement of policies and guidelines proposed to be followed; and b) a summary of operations proposed to be undertaken. -

Low Flammability Local Native Species (Complete List)

Indicative List of Low Flammability Plants – All local native species – Shire of Serpentine Jarrahdale – May 2010 Low flammability local native species (complete list) Location key – preferred soil types for local native species Location Soil type Comments P Pinjarra Plain Beermullah, Guildford and Serpentine River soils Alluvial soils, fertile clays and loams; usually flat deposits carried down from the scarp Natural vegetation is typical of wetlands, with sheoaks and paperbarks, or marri and flooded gum woodlands, or shrublands, herblands or sedgelands B Bassendean Dunes Bassendean sands, Southern River and Bassendean swamps Pale grey-yellow sand, infertile, often acidic, lacking in organic matter Natural vegetation is banksia woodland with woollybush, or woodlands of paperbarks, flooded gum, marri and banksia in swamps F Foothills Forrestfield soils (Ridge Hill Shelf) Sand and gravel Natural vegetation is woodland of jarrah and marri on gravel, with banksias, sheoaks and woody pear on sand S Darling Scarp Clay-gravels, compacted hard in summer, moist in winter, prone to erosion on steep slopes Natural vegetation on shallow soils is shrublands, on deeper soils is woodland of jarrah, marri, wandoo and flooded gum D Darling Plateau Clay-gravels, compacted hard in summer, moist in winter Natural vegetation on laterite (gravel) is woodland or forest of jarrah and marri with banksia and snottygobble, on granite outcrops is woodland, shrubland or herbs, in valleys is forests of jarrah, marri, yarri and flooded gum with banksia Flammability -

Trees of W.A. Jarrah and Karri

Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 3 Volume 1 Number 1 January- February,1952 Article 14 1-1952 Trees of W.A. Jarrah and Karri C. A. Gardner Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/journal_agriculture3 Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Gardner, C. A. (1952) "Trees of W.A. Jarrah and Karri," Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 3: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/journal_agriculture3/vol1/iss1/14 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 3 by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J >* A'% t •v "*" , '•fc^rW/** *J?J!£ ^* r*#i »«4. '.^aSf «. f ip^M* Pr^ ft. • # w &fr;- •* jft.,r.!^^« " Journall of agriculture Vol. 1 19 Jan.-Feb., 1952] JOURNALOF AGRICULTURE, W.A. 77 TREES OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA *2* C. A. GARDNER, (Government Botanist) w/l "• •' "'---^"ll1tH.^ J»M TN commencing this series, in which a large number of trees will be dealt with, •I first place must be given to the species of Eucalyptus which include, besides the gum-trees, the various shrubs and mallees which make up a considerable part of the woody flora of South-Western Australia. It is hoped that these articles may sometimes distinct, sometimes obscure, prove of interest and value, for apart and sometimes the intramarginal nerve from the trees which provide us with may be so close to the leaf-margin as our local timber, some species of to be contiguous with it.