Abstract No: 5202 SUSTAINABLE BUILDINGS - TOKYO 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caturanga Vielle

Le caturaṅga classique préservé au Kerala Christophe VIELLE F.R.S.-FNRS - UCL, Louvain-la-Neuve Le caturaṅga est un jeu de stratégie indien antique, dont la forme originale est à l’origine de notre jeu d’échec moderne. Le mot, du genre neutre en sanskrit (caturaṅgam), s’interprète comme un composé bahuvrīhi subsantivé signifiant « (celui) qui a quatre (catur-) corps (aṅga-) » (catvāri aṅgāni yasya), celui-ci pouvant désigner une armée au complet c’est-à-dire l’« [armée = balam] pourvue de [ses] quatre corps », ou alors le « [jeu = krīḍanam] aux/des quatre corps [d’armée] », en référence à la doctrine militaire indienne classique selon laquelle « l’armée (depuis le Mahâbhârata) se répartit en quatre grands corps, dont toute la littérature ultérieure reprend l’énumération : selon la hiérarchie usuelle, d’abord les éléphants, puis la cavalerie, les chars, enfin l’infanterie »1 — avec au centre le roi et son ministre ou conseiller (chef d’armée), cette hiérarchie (de statut et de disposition théoriques) étant en effet, comme on va le voir, celle reflétée symboliquement dans le jeu2. La plus ancienne allusion certaine à ce jeu dans la littérature sanskrite se trouve au début du 7e siècle de notre ère dans le Harṣacarita (Geste du roi Harṣa, ucchvāsa 2) de Bāṇa, qui parle d’un royaume en paix où les (seuls) quatre corps d’armée (que l’on rencontre) sont ceux des plateaux (de jeu) : asmiṃś ca rājani (…) aṣṭāpadānāṃ caturaṅgakalpanā, « et sous ce roi (…) la (seule) disposition en quatre corps (d’armée) (était celle) des échiquiers »3. Le nom (composé bahuvrīhi substantivé) du damier lui-même, aṣṭāpada (« celui qui a huit pieds/cases »), est attesté à une date plus ancienne. -

Socio-Cultural Influence in Built Forms of Kerala

International Journal for Social Studies Volume 01 Issue 01 Available at November 2015 http://edupediapublications.org/journals/index.php/IJSS Socio‐Cultural Influence in Built Forms of Kerala Akshay S Kumar Research Scholar, NIT Calicut, Kerala ABSTRACT kinds of influences, including Brahmanism, contributed to the cultural diffusion and Similarities in climate, it is natural that the architectural tradition. More homogeneous environmental characteristics of Kerala are artistic development may have rigorously more comparable with those of Southeast occurred around the 8th century as a result of Asia than with the rest of the Indian large-scale colonization by the Vedic subcontinent. Premodern architecture in (Sea Brahmans, which caused the decline of of Bengal) must have shared common Jainism and Buddhism. traditions with Southeast Asian architecture, which is wet tropical architecture. Because the Western Ghats isolated Kerala INTRODUCTION from the rest of the subcontinent, the infusion of Aryan culture into Kerala. It came only Kerala architecture is a kind of after Kerala had already developed an architectural style that is mostly found in independent culture, which can be as early as Indian state of Kerala and all the 1000 B.C. (Logan 1887). The Aryan architectural wonders of kerala stands out to immigration is believed to have started be ultimate testmonials for the ancient towards the end of the first millennium. vishwakarma sthapathis of kerala. Kerala's Christianity reached Kerala around 52 A.D. style of architecture is unique in India, in its through the apostle Thomas. The Jews in striking contrast to Dravidian architecture Kerala were once an affluent trading which is normally practiced in other parts of community on the Malabar. -

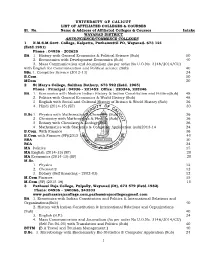

1 University of Calicut List of Affiliated Colleges

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT LIST OF AFFILIATED COLLEGES & COURSES Sl. No. Name & Address of Affiliated Colleges & Courses Intake WAYANAD DISTRICT ARTS/SCIENCE/COMMERCE COLLEGES 1 N.M.S.M.Govt. College, Kalpetta, Puzhamuttil PO, Wayanad- 673 121 (Estd.1981) Phone : 04936 - 202625 BA 1. History with General Economics & Political Science (Sub) 50 2. Ecconomics with Development Economics (Sub) 40 3. Mass Communication and Journalism (As per order No U.O.No. 3146/2014/CU) with English for Communication and Political science (Sub) 40 BSc.1. Computer Science (2012-13) 24 B.Com 50 MCom 20 2 St Mary's College, Sulthan Bathery, 673 592 (Estd. 1965) Phone : Principal : 04936 - 221452 Office : 220246, 225246 BA 1. Economics with Modern Indian History & Indian Constitution and Politics(Sub) 48 2. Politics with General Economics & World History (Sub) 48 3 English with Social and Cultural History of Britain & World History (Sub) 36 4. Hindi (2014-15) (SF) 30 B.Sc 1. Physics with Mathematics & Chemistry (Sub) 36 2 Chemistry with Mathematics & Physics (Sub) 36 3 Botany with Chemistry & Zoology (Sub) 36 4 Mathematics with Statistics & Computer Application (sub)2013-14 24 B.Com With Finance 36 B.Com with Finance (SF)(2015-16) 40 BBA 30 BCA 24 MA Politics 15 MA English (2014-15) (SF) 20 MA Economics (2014-15) (SF) 20 M.Sc. 1. Physics 12 2. Chemistry 12 3. Botany (Self financing – 2002-03) 12 M.Com Finance 15 M.Com (SF) (2015-16) 15 3 Pazhassi Raja College, Pulpally, Wayanad (Dt), 673 579 (Estd.1982) Phone: 04936 – 240366, 243333 www.pazhassirajacollege.com,[email protected] BA 1. -

Kerala and South Kanara Traditional Architecture Dr

Published by : International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) http://www.ijert.org ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 9 Issue 12, December-2020 Living the Common Styles- Kerala and South Kanara Traditional Architecture Dr. Lekha S Hegde 1 1 Professor, BMS College of Architecture, Bull Temple road, Basavangudi, Bangalore- 560019, Visvesvaraya Technological University, India. Abstract— This article focuses on the similarities of the domestic ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS culture which is reflected in the Architecture of these geographies Nalukettu is typically a rectangular structure where four halls namely Kerala and South Kanara. We need to study the rich are joined together with a central court-yard open to the sky. Traditional Architecture of these identified regions. In this The four halls on the sides are named: interesting search, the amazing facts regarding similarities Vadakkini (northern block), between Kerala’s traditional Nalukettu houses and traditional Manor houses of South Kanara need to be highlighted. The Padinjattini (western block), Nalukettu is the traditional style of architecture of Kerala where Kizhakkini (eastern block) and in an agrarian setting a house has a quadrangle in the centre. Thekkini (southern block) Originally the abode of the wealthy Brahmin and Nair families, The outer verandahs along the four sides of the Nalukettu are this style of architecture has today become a status symbol enclosed differently. While both the western and eastern verandahs among the well-to-do in Kerala. Nalukettu is evident in the are left open, the northern and southern verandahs are enclosed or traditional homes of the upper class homestead where customs semi-enclosed [2]. and rituals were a part of life. -

Spatial Configurations of Granary Houses in Kanyakumari, South India

ISVS e-journal, Vol. 2, no.3, January, 2013 ISSN 2320-2661 Arapura: Spatial Configurations of Granary Houses in Kanyakumari, South India Indah Widiastuti School of Architecture Planning and Policy Development Institute of Technology Bandung, Indonesia & Ranee Vedamuthu School of Architecture and Planning Anna University, Chennai, India Abstract Arapura in this discusion refers to traditional residential building that accommodates agriculturist matrilineal joint-family (taravad) in Kanyakumari area. This paper outlines the evolution of the Arapura from the prototype of granary whose sequential transformation could be traced from the design of granary box, pattayam. Three cases of Arapura are documented and analyzed with respect to their spatial configurations. Keywords: arapura, veedu, nira granary-house, granary-box, Kerala, matrilineal, Kanyakumari, India and. Introduction Arapura refers to the main house within a traditional residential complex or house compound (veedu) in Kanyakumari area; South India. A veedu accommodates an agriculturist matrilineal joint family that constitutes a matrilineal-clan (taravad)i and the Arapura stands for the main building of a veedu, main granary, ancestral house and worshiping center of the matrilineal joint family. Local people also address arapura as thaiveedu or ‘mother’s house’ signifying ownership and inheritance that follow female lines. Kanyakumari is a region located on the inter-state border area that partially belongs to the administrative districts of Kanyakumari, Tamil Nadu State and Thiruvananthapuram, of Kerala State. Kanyakumari is a region characterized by wet tropical climate with large forest reserves, high rain fall, high humidity that can rise to about 90 percent and hundreds of water bodies and a canal irrigation system. -

HOLISTIC CENTRE Pg. 1

HOLISTIC CENTRE pg. 1 VISVESVARAYA TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY “Jnana Sangama”, Belgaum – 590 018 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN PROJECT (THESIS) 2016 – 2017 “HOLISTIC CENTRE, KERALA” In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Bachelor of Architecture Submitted by: RAYANA RAJ Guide: Prof. Ar. KINJAL SHAH ACHARYA’S NRV SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE (AFFLIATED TO VTU, BELGAUM, ACCREDITED BY COA, AICTE, NEW DELHI) Acharya Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan Road, Soldevanahalli, Bangalore – 560090 HOLISTIC CENTRE pg. 2 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that this is a bonafide record of the Architectural Design Project completed by Ms. RAYANA RAJ of VIII semester B.Arch, USN number 1AA13AT073 on project titled “HOLISTIC CENTRE” in Thrissur, Kerala, India. This has been submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of B. Arch awarded by VTU, Belgaum during the year 2016-2017. Dean, Ar. Kinjal Shah, Acharya’s NRV School of Architecture, Thesis Guide, Bangalore -560107 Assistant Professor External examiner 1 External examiner 2 HOLISTIC CENTRE pg. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Completion of this thesis was possible with the support of several people. I am grateful to Prof. Vasanth K. Bhat, Prof. Anjana Biradar and our thesis Coordinator Prof. Priya Joseph for inspiring us to achieve success in all our endeavors. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my thesis guide, Prof. Kinjal Shah for her constant guidance and support. I am extremely happy to mention my special thanks to our motivating thesis panel for their encouragement and supervision. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Prof. Shwetha Mattoo for her advice and motivation. -

Kerala History Timeline

Kerala History Timeline AD 1805 Death of Pazhassi Raja 52 St. Thomas Mission to Kerala 1809 Kundara Proclamation of Velu Thampi 68 Jews migrated to Kerala. 1809 Velu Thampi commits suicide. 630 Huang Tsang in Kerala. 1812 Kurichiya revolt against the British. 788 Birth of Sankaracharya. 1831 First census taken in Travancore 820 Death of Sankaracharya. 1834 English education started by 825 Beginning of Malayalam Era. Swatithirunal in Travancore. 851 Sulaiman in Kerala. 1847 Rajyasamacharam the first newspaper 1292 Italiyan Traveller Marcopolo reached in Malayalam, published. Kerala. 1855 Birth of Sree Narayana Guru. 1295 Kozhikode city was established 1865 Pandarappatta Proclamation 1342-1347 African traveller Ibanbatuta reached 1891 The first Legislative Assembly in Kerala. Travancore formed. Malayali Memorial 1440 Nicholo Conti in Kerala. 1895-96 Ezhava Memorial 1498 Vascoda Gama reaches Calicut. 1904 Sreemulam Praja Sabha was established. 1504 War of Cranganore (Kodungallor) be- 1920 Gandhiji's first visit to Kerala. tween Cochin and Kozhikode. 1920-21 Malabar Rebellion. 1505 First Portuguese Viceroy De Almeda 1921 First All Kerala Congress Political reached Kochi. Meeting was held at Ottapalam, under 1510 War between the Portuguese and the the leadership of T. Prakasam. Zamorin at Kozhikode. 1924 Vaikom Satyagraha 1573 Printing Press started functioning in 1928 Death of Sree Narayana Guru. Kochi and Vypinkotta. 1930 Salt Satyagraha 1599 Udayamperoor Sunahadhos. 1931 Guruvayur Satyagraha 1616 Captain Keeling reached Kerala. 1932 Nivarthana Agitation 1663 Capture of Kochi by the Dutch. 1934 Split in the congress. Rise of the Leftists 1694 Thalassery Factory established. and Rightists. 1695 Anjengo (Anchu Thengu) Factory 1935 Sri P. Krishna Pillai and Sri. -

Living Culture and Typo-Morphology of Vernacular-Traditional Houses in Kerala

Indah Widiastuti Susilo 1 The Living Culture and Typo-Morphology of Vernacular-Traditional Houses in Kerala Indah Widiastuti Susilo Introduction The term “vernacular architecture” stands for the art of constructing buildings and shelters which is spontaneous, environment-oriented, community-based; it acknowledges no architect or treaty and reflects the technology and culture of the indigenous society and environment (Rudofsky 1964: 4). Vernacular architecture is the opposite of high traditional architecture which belongs to the grand tradition (e.g. palace, fortress, villa, etc.) and requires special skills and expertise which an architect must have knowledge of and for which he enjoys a special position (Rapoport 1969). This paper is a chronicle of observations of traditional vernacular houses in the whole region of Kerala done within nine months The research methods used include observation and photography-documentation of more than 50 traditional-vernacular houses in Kerala State and 30 more random places in other states for comparison. Experts and builders were also interviewed. The object of study is to find patterns and sources of settlement, buildings, living cultures and local indigenous knowledge. Location of samples are in the districts of Shoranur, Pattambi, Pallipuram, Calicut, Palghat, Aranmula, Chenganur, Tiruvalla, Kottayam, Ernakulam-Cochin, Tripunitura, Perumbavur, Mulanthuruti, Piravom, Trivandrum, Kanyakumari, Attapadi, and Parapanangadi. From these places, 52 samples of traditional- vernacular residential architecture of Kerala were observed. These samples cover ordinary commoner houses, the traditional courtyard house and the single mass house, as well as the non- Kerala vernacular houses and houses with colonial vernacular architecture. The research method utilized is the Typo-morphology analysis (Argan 1965, Moneo 1978) which examines existing types of residential houses and their complementary. -

Memoirs of Vaidyas. the Lives and Practices of Traditional Medical

Memoirs of Vaidyas The Lives and Practices of Traditional Medical Doctors in Kerala, India (7)* TSUTOMU YAMASHITA** Kyoto Gakuen University, Kyoto, Japan P. RAM MANOHAR AVP Research Foundation, Coimbatore, India Abstract This article presents an English translation of an interview with a practition- er of traditional Indian medicine (Āyurveda), A. S. M*** N*** (1930 ~ ), in Kerala, India. The interviewee’s specialized field is traditional poison-healing (Viṣavaidya). The contents of the interview are: 1. History of the Family (1.1 Family Members, 1.2 Teachers, 1.3 Joint Family, 1.4 Elephant, 1.5 Father, 1.6 Tradition of the Veda), 2. Traditional Poison-healing (Viṣavaidya) (2.1 Textual Tradition, 2.2 Kōkkara Nampūtiriʼs Reformation, 2.3 Speciality of Treatments and Medicines in Kerala, 2.4 Treatment Methods, 2.5 Modern Medicine and Āyurveda, 2.6 Signs of Death, 2.7 Prevision, 2.8 Treatment fee, 2.9 Hydropho- bia, 2.10 Mantra, 2.11 Features of Messengers (dūtalakṣaṇa), 2.12 Amtakalā and Viṣakalā), 3. Treatments for Elephants, and Bibliography. Key words Ayurveda, Traditional Indian Medicine, Poison-healing, Kerala * We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Vaidya A. S. M*** N*** for accepting our interview and allowing the translation to be published. ** Author for correspondence. Address: 1-1 Nanjo Otani, Sogabe-chou, Kameoka-shi, Kyoto-fu, 621-8555 Japan. E-mail: [email protected]. eJournal of Indian Medicine Volume 6 (2013), 45–90 46 TSUTOMU YAMASHITA & P. RAM MANOHAR Introduction We would like to introduce here an English translation of one of our interviews. The interviewee, A. -

Early Medieval Temples of Eranad: a Study of Karikkat, Pulpatta and Trippanachi

Early Medieval Temples of Eranad: A Study of Karikkat, Pulpatta and Trippanachi Arya Nair V. S.1 1. Department of History, University of Calicut, Malappuram, Kerala, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 25 July 2017; Revised: 18 September 2017; Accepted: 13 November 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 556 ‐566 Abstract: Early medieval period (c. 9th – 12th century CE) marked a remarkable change in the socio‐ cultural and political history of Kerala. The migration of Brahmins and corresponding changes occurred in the worshipping pattern as well as the expansions of agriculture are some of the noteworthy features of this period. Almost all structural temples, both Saivite and Vaishnavite, were developed in this period. The early medieval temples of Eranad, one of the northern most political sub units of early medieval Chera state, was also the outcome of this cultural environment. This article focuses on three temples; Karikkat, Pulpatta and Trippanachi that developed in connection with the Brahmin settlement of Eranad. The architectural features of these temples have shown that they are built in typical Kerala style and belonged to early medieval period. These three temples had a decisive space in the early medieval socio‐ political settings of Eranad. Keywords: Early Medieval Kerala, Temple Architecture, Kerala Style, Eranad, Pulpatta, Trippanachi, Karikkat Introduction Eranad is one of the seven Taluks in the present Malappuram district of Kerala. It was part of the erstwhile Malabar district of colonial India under Madras presidency (Logan (1887) 2010). In the pre‐colonial time (from 13th to 18th century CE) Eranad was a political unit under the control of Zamorins of Calicut (Ayyar (1938) 1997, Nambuthiri 1986, Haridas 2016) and in the early medieval time (from 9th to 12th century CE) it was one of the fourteen provincial subdivisions called Nadu of Chera state (Narayanan (1996) 2013). -

A Prelude to the Study of Indigenous, Pre-European, Church Architecture of Kerala

DOI: 10.15415/cs.2014.12008 A Prelude to the Study of Indigenous, Pre-European, Church Architecture of Kerala Sunil Edward Abstract Christianity is believed to have been first introduced to Kerala in 52 CE through St. Thomas, the Apostle. This paper introduces the traditional indigenous Church architecture of Kerala that existed before the arrival of Portuguese in 1498 CE. The paper mainly looks into the circumstances under which it got destroyed and also analyses the reasons for its disappearance. The paper concludes that after the arrival of the Europeans and, in their initiative to bring the Kerala church closer to the Western church, they constituted a conscious attempt to alter the religious architecture of traditional Kerala Christians, declaring that it was Hindu by nature. Their intervention caused an irreparable break in the age-old system, and introduced a totally new and alien style to the traditional church building character, form and scale, forcing the traditional church architecture of centuries to be wiped off forever. Keywords: Indigenous; Church Architecture; Kerala; Portuguese; Information Sources INTRODUCTION Calicut, 1498 AD: Vasco da Gama entered the entrance gateway of the Church complex and proceeded to the Church building. He was happy to go to the Church after the long and uncertain ship journey. Uncertain, as an explorer, going to a new land always had an uncertainty in it, but he loved it. It’s the satisfaction one gets in reaching the destination, a new land, that counts. He liked this new land too, which his men called the ‘Serra’, Portuguese word for the mountain. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2017-2374

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: LNG2014-1176 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2017-2374 Scrutinizing the Role of Cultural Spaces as a Common Factor in Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage Devakumar Thenchery Assistant Professor MES College of Architecture India 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2017-2374 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. This paper has been peer reviewed by at least two academic members of ATINER. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research This paper should be cited as follows: Thenchery, D. (2018). "Scrutinizing the Role of Cultural Spaces as a Common Factor in Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage", Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: ARC2017-2374. Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN: 2241-2891 31/01/2018 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2017-2374 Scrutinizing the Role of Cultural Spaces as a Common Factor in Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage DevakumarThenchery Abstract Intangible cultural heritage has been a well discussed subject and has been receiving evenmore consideration in thelast decades because of the approach by UNESCO.