From the Caves and Jungles of Hindustan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monthly Journal Devoted to Oriental Philosophy, Art, Literature and Occultism:· Embracing Mesmerism, Spiritualism, and Other Secret Sciences

A MONTHLY JOURNAL DEVOTED TO ORIENTAL PHILOSOPHY, ART, LITERATURE AND OCCULTISM:· EMBRACING MESMERISM, SPIRITUALISM, AND OTHER SECRET SCIENCES. .. VOL. 4. No.8. MADR.AS, MAY, 1883. ?olumns, in order that justice be strictly dealt out j but l~ ra~he}' proceeds to have the M8S. handed to it for pub. lIcatlOn, opened, and carefully read before it can consent 'l'HERE IS NO REIJIGION HIGHER THAN TRUTH. to send it over to its printers. Anable article has never [Family motto of the lIfaharajahs of Benares. ] sought admission into our pages and been rejected for its advocating any of the religious doctrines or views to -J- which its conductor felt personally opposed. On the TO TIlE" DISSATISF'IED." other hand, the editor has never hesitated to give any olle of the above said religions and doctrines its dues, WE have belief in the fitness and usefulness of impar and speak out tho truth whether it pleased a certain fac tial critici1:llll, and, even at time1:l, in that of a judicious tion of its sectarian reader:s) or not. \Ve neither court onslaught upon some of the many creeds and philoso nor claim favonr. N or to satisfy the sentimental emo-· phies, as we have in advocating the publication of all tions and susceptibilities of some of ollr readers· do we such polemics. Any sane man acquainted with human feel prepared to allow our columns to appeal' colourless, nature, must see that this eternal" taking on faith" of least of all, for fear that our own house should be shown the lllost absurdly conflicting dogmas in our age of as 'also of glass.' " scientific progre1:ls will never do, tlH1t it is impossible • that it can last . -

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

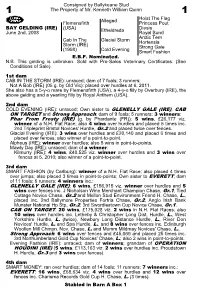

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Western Indologists: a Study in Motives

Agniveer http://agniveer.com DISTORTION OF BHARTIYA HISTORY: SOME CAUSES WESTERN INDOLOGISTS: A STUDY IN MOTIVES BY PT. BHAGVAD DATT RESEARCH SCHOLAR (EDITED BY DR. VIVEK ARYA) Agniveer http://agniveer.com Preface by Pt.Bhagavad Data research scholar The present monograph is an amplified English version of the first argument of chapter III of my Bharatavarsha ka Brihad Itihasa Vol I (published in 1951). I have under taken this task in response to persistent requests from friends and scholars who read that volume in advance proofs and also in its published form. Being hard pressed for time, I requested my friend Prof. Sadhu Ram, M.A., to prepare the English version for me. He was kind enough to comply with my request, and placed the manuscript at my disposal by the end of 1950. Further material was added to it, and the monograph assumed the present shape. There is a widespread belief among Indian scholars and the educated public that western Orientalists and indologists have been invariably actuated by purely academic interests, pursued in an objective, scientific and critical spirit. While some of them have undoubtedly approached their task in an unimpeachable manner, it is not so well-known that a vast majority of them, who have exercised tremendous influence in the world of scholarship, have been motivated by extraneous considerations, both religious and political. It is the object of this study to throw some light on this important aspect of western scholarship. I have been reluctantly driven to the painful conclusion that the bulk of what today passes as ‘scientific’, ‘objective’ and ‘critical’ research, is, in fact, vitiated by the underlying and subtle influence exercised by none too academic motives. -

Ari Trocou De Advogado Às De Seu Julgamento Fésperas ANGELA AQUIS MMM IÇÕES DE

¦r:r*~mifô&*.y *imç strt^ir^-^-r^r-i^rf1''^ '^% ?*f vi *r**g^-ft ^r^mí,rmvr^i^r i... q^rqyi f rf^gi» BIBUOTEOA NlOIONATj ^VB|M AVENIDA RIO BRÀNUO i.l.u tíbkJ-iiftiiàwkl.k CAPITAR jg-apsai»^ «B^a^S»»^^ ¦mnMSKO SAMBENTA DCS ÚLTIMOS FOCOS REBELDES NO PANAMÁ i TEi.rnRAMA taciiía i il tim 'illi tu llilWpppifWÉ^ séEaBBaKrBtçí-i- wsheesekb^(i.K.iA na 7) wmm^ÉÉàiismmàm^Ê CVIldUU«sa ra n ^si ww v* ^^ cll'¦w ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ 0^r ¦ iUH.0^j w*» V ¦ ^% oipe de Estado USBQft, 7 (UPI — Urgente) — 0 ministro h Inferior, sr. Arnaldo Sclwhi, revBÍou /loje rjue foi fri/sfnvfif. orno tentativa r/e revolução em Porfugoí «o iiièí êe iiifíiço último. Acrescentou o ministro que no ocasião íornm dctnlns 31 pes- sooj, sendo 22 civis e 9 militares, Mais detalhes na pc/ginci 7. •-^affiaraaçsBí SJER^ RÊV/V/DO 0 ASSASSifilO Dl HILWA AMOROSO "liai "barbudo" mais As dos lunins brasileira e cubano tini charuto ann" r n lnlrr funil ba- tiniir. n tinina idealista rir Fidel Castro estere qualidades foram dn Cas- comparadas ontem na nlntfiçn oferecido pelo presiden- /oradas dr um nutro ctiointn baiano, Este Ini um dos acesa dr, 71/e nunca nn i-ntnírin da Esplanada as o te Juscelino Kubitschek no primeiro ministro Fuiri muitos aspertn-, pitorescos observados livremente peln-, Irh durante o qual taram relembrados causas durante 00 minutos. Ari Trocou de Advogado às Castra, quando o chefe do gorcrno brasileira fumou jornalistas no almoço tio Palácio dns Laranjeiras, A efeitos da derrubado de. -

CLASSIC...Albert the Great(Go for Gin), Who Will Be Trying to End a Three-Race Los- Ing Streak When He Starts in the Classic, Br

Tuesday, Thoroughbred Daily News October 23, 2001 TDN For inform ation, call (732) 747- 8060. HEADLINE NEWS said. As for Kona Gold, trainer Bruce Headley said, “He was CLASSIC...Albert The Great (Go For Gin), jum ping and squealing when he pulled up. He’s com ing up who will be trying to end a three- race los- to the race perfect.” ing streak when he starts in the Classic, BESSEMER TRUST JUVENILE...The three favorites for Satur- breezed five furlongs in 1:02 over the day’s race recorded solid works yesterday m orning. GI Belm ont m ain track yesterday m orning. Cham pagne S. winner O ffic e r (Bertrando), who loom s the “That was the plan, we didn’t want to go too fast,” said heaviest favorite on the card, stopped trainer Bob Baffert’s trainer Nick Zito. Jockey Jorge Chavez was in the saddle for clock in :59 2/5 for five furlongs at Santa Anita. “He the m ove and w ill be back aboard the Tracy Farm er- ow ned worked great,” the conditioner said of his unbeaten colt. “It four- year- old Saturday. Gary Stevens rode the bay to a was a nice steady five-eighths. I clocked him going out fourth-place finish in the GI Jockey Club Gold Cup Oct. 6. three- quarters in 1:11.74. He was really aggressive and he “Jorge worked him in 1:05 before the Classic last year and didn’t get tired.” John Toffan and Trudy McCaffery’s he ran fourth,” Zito continued. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 4/29/07 • PAGE 2 of 10

CHINESE DRAGON wins off 12-month HEADLINE break...p. 2 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2007 SIMPLY DIVINE THE CAT’S MEOW Stepping up to stakes company for the first time GII Illinois Derby and GIII Gotham S. winner Cowtown yesterday in the GIII Withers S., Divine Park (Chester Cat (Distorted Humor) posted the second-fastest time House) led nearly every step to for yesterday=s five-eighths breeze at maintain his perfect record. AHe Keeneland, covering the distance in stepped his game up a couple of :58.60 (video) while breezing in com- notches,@ said Artie Magnuson, pany with stablemate Magnificent assistant to winning trainer Kiaran Song. After a final quarter in :22 3/5, McLaughlin. AWe=re definitely going the chestnut galloped out in 1:11. in the right direction.@ The bay will AThat=s as good as a horse can work continue his rise up the class lad- right there,@ said trainer Todd Divine Park der, but his next start isn=t yet cer- Pletcher. AHe went very well and fin- Adam Coglianese photo tain. AHe=s a special horse,@ ished up strong.@ Pletcher=s four other Cowtown Cat Magnuson added. AThere=s the Pe- GI Kentucky Derby hopefuls--Any Adam Coglianese photo ter Pan [GII, 9f, BEL, May 20] and the Preakness [GI, Given Saturday (Distorted Humor), $1 million, 1 3/16m, PIM, May 19]. [Owner] Jim [Barry] Circular Quay (Thunder Gulch), Sam P. -

Out of Sight*

ikramullah Out of Sight* It was an august afternoon. The sun, lodged in a sky washed clean by the rain, stared continuously at the world with its wrathful eyes. By that time, the traffic had died down and the main bazaar of the town of Sultan- pur had become completely deserted. The pitch-black road lying senseless in the middle of the bazaar, soaking wet with perspiration, had taken on an even darker hue. The shopkeepers sat quietly in their shops behind awnings fastened to bamboo poles extending out to the road. What wretch would leave his house in such weather to go shopping? Sitting on the chair inside his shop, Ismail saw his friendís eight- or ten-year-old son Mubashshir pass by under his awning, walking backwards with a satchel around his neck. A smile suddenly appeared on Ismailís face. Kids will be kids, he thought. Feeling bored and alone since he couldnít find anything to interest him, he had devised this private pastime of walking home backwards. Ismail called him over: ìHey Mubashshir, come here!î ìComing Baba Ji,î saying that, the boy climbed the two wooden-plank stairs and stood facing Ismail. His demeanor showed respect and his won- dering eyes were asking, ìWhatís the matter?î ìWhy are you walking backwards? Want to bump into some bicyclist or pedestrian?î ìNo, Baba Ji, Iím careful. Every now and then I turn around to look.î ìDonít act silly. Walk straight up the road, face forward. Do you understand?î The boy said yes, and as he started going down the two steps Ismail asked, ìIs your father back from Lahore yet?î ìNo. -

Toward a Genealogy of Aryan Morality: Nietzsche and Jacolloit Thomas Paul Bonfiglio University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Faculty Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Publications 2006 Toward a Genealogy of Aryan Morality: Nietzsche and Jacolloit Thomas Paul Bonfiglio University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/mlc-faculty-publications Part of the History of Philosophy Commons This is a pre-publication author manuscript of the final, published article. Recommended Citation Bonfiglio, Thomas Paul, "Toward a Genealogy of Aryan Morality: Nietzsche and Jacolloit" (2006). Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Faculty Publications. 11. http://scholarship.richmond.edu/mlc-faculty-publications/11 This Post-print Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Toward a Genealogy of Aryan Morality: Nietzsche and Jacolliot Thomas Paul Bonfiglio While Nietzsche’s writings of the late 1880s reveal waxing interests in Hinduism, Sanskrit philology, Aryan culture, and the related Indo-European hypothesis, these interests have been remarkably understudied by Nietzsche scholarship, with the exception of a scant few articles that have recently appeared.1 The presence of the aforementioned topics was crucial for the configuration of the works written in 1887 and 1888: On the Genealogy of Morality, The Twilight of the Idols, and The Antichrist, as well as for some of the notions at hand in Nietzsche’s correspondence with Heinrich Köselitz, but the provenance of the ideas that codetermined those works and generated their philosophies has never been properly examined. -

Fqp3p3qewe4o9fnuzuazjw8qv

JTBC the most loved and trusted network by Koreans everywhere is now celebrating its 7th anniversary After growing in leaps and bounds over the past seven years, JTBC is again undertaking a ‘challenge’ Coloring your World, JTBC 3 JTBC had been working tirelessly over the past 7 years to provide differentiated contents in the changing global media industry. ‘Newsroom’ has become one of the nation’s most popular programs, attracting the largest audience in Korean history, providing coverage of landmark events, such as the Inter-Korean Summit. Starting with the drama ‘Rain or Shine’ JTBC has continued to expand its lineup with the addition of a Monday-Tuesday drama slot, increasing its depth and diversity. Also by producing hit dramas like ‘SKY Castle’ ‘Misty’ ‘Something in the Rain’ and ‘The Beauty Inside’, JTBC received rave reviews in the aspects of both quality and entertainment. The consecutive successes of JTBC’s season-based, non-scripted programs including ‘Sugar Man’ ‘Hyori’s Bed and Breakfast’ and ‘Hidden Singer’ have proven that JTBC is a broadcaster trusted and watched by many. ‘Wassup Man’ reached new heights in cross-media application by accumulating over 1.6 million subscribers on its YouTube channel. This marked the first time a digital non-scripted program produced by a domestic broadcasting company gained that many subscribers on YouTube. The JTBC media family—which includes JTBC2, JTBC3 FOX Sports, JTBC4 and JTBC Golf —have played a pivotal role in all areas of society from entertainment to lifestyle and sports. Going forward, JTBC will stop at nothing to provide viewers with even better content. -

Imagining Macrohistory? Madame Blavatsky from Isis Unveiled (1877) to the Secret Doctrine (1888) Garry W

Imagining Macrohistory? Madame Blavatsky from Isis Unveiled (1877) to The Secret Doctrine (1888) Garry W. Trompf In Memoriam: Alfred John Cooper1 Introduction The term „macrohistory‟ denotes the envisaging and representation of the human past as a vast panorama, great movements of human activity held „in the mind‟s eye‟ or in a unitary vision. When such broad encompassments also incorporate the pre-human past and even the possible future of everything, then one may refer to cosmological macrohistory (or „cosmo-history‟), or, if the atmosphere of a mythos is strong, to a mythological macrohistory. Many will suspect that mental acts of encapsulation entailed in „doing macrohistory‟ are inevitably unreliable and methodologically inadmissible because the myriad facts to be embraced, both known and unknown, could never be accounted for in any one synoptic view. Certainly the macrohistorical visionary will have to resort to a picturing or imaging through some kind of model, paradigm or diagrammatic procedure, and in almost all cases, a species of meta-history (of a conceptual „framing‟ superimposed on data) will result. In the Judaeo- Christian-Islamic-Marxist trajectory of thought, four primary „idea-frames‟ of macrohistory have stood out. These are, first, progress, or the idea that past events show an overall improvement of things; second and contrarily, regress, the outlook that affairs have steadily worsened; third, recurrence, the apprehension that everything is basically repetitive (if not cyclical); and lastly, the view that nothing can be fully understood without a sense of an utterly final consummation, an eschaton (end) or apokatastasis (restoration of all things) or millennial „showdown‟, as against some limited telos.