Meditations on Frantz Fanon's Wretched of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Power to the People! the Black Panther Party and Beyond (US, 1998, 115 Minutes) Director: Lee Lew Lee Study Guide

All Power To The People! The Black Panther Party and Beyond (US, 1998, 115 minutes) Director: Lee Lew Lee Study Guide Synopsis All Power To The People! examines problems of race, poverty, dissent and the universal conflict of the “haves versus the have nots.” US government documents, rare news clips, and interviews with both ex-activists and former FBI/CIA officers, provide deep insight into the bloody conflict between political dissent and governmental authority in the US of the 60s and 70s. Globally acclaimed as being among the most accurate depictions of the goals, aspirations and ultimate repression of the US Civil Rights Movement, All Power to the People! Is a gripping, timeless news documentary. Themes in the film History of the Civil Rights Movement Black Panther Party FBI’s COINTELPRO American Indian Rights Movement Political Prisoners in the US Trials of political dissidents such as the Chicago 7 trial Study Questions • Why did the FBI perceive the Black Panther Party as a threat? • How did the FBI’s COINTELPRO contribute to the destruction of the Black Panther Party? • What do you know about Fred Hampton? • Can you name any former members of the Black Panther Party? • Throughout US history, what are some of the organizations that have been labeled as “troublemakers” by the FBI? • In your opinion, why were these groups the target of FBI investigations and operations such as COINTELPRO? • Do you think this kind of surveillance and disruption of dissent exists today? • In this film, we see clips of leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X and Huey Newton. -

Revolutionary Peoples' Constitutional Convention September 1970, Philadelphia Workshop Reports1

Revolutionary Peoples' Constitutional Convention September 1970, Philadelphia Workshop Reports1 WORKSHOP ON INTERNATIONALISM AND RELATIONS WITH LIBERATION STRUGGLES AROUND THE WORLD The Revolutionary Peoples' Constitutional Convention supports the demand of the Chinese people for the liberation of Taiwan. We demand the liberation of Okinawa and the Pacific Territories occupied by U.S. and European imperialist countries. The Revolutionary Peoples' Constitutional Convention supports the struggles and endorses the government of the provisional revolutionary government of South Vietnam, the royal government of National Union of Cambodia, and the Pathet Lao. Huey P. Newton Minister of Defense Black Panther Party In order to insure our international constitution, we, the people of Babylon, declare an international bill of rights: that all people are guaranteed the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, that all people of the world be free from dehumanization and intervention in their internal affairs by a foreign power. Therefore, if fascist actions in the world attempt to achieve imperialist goals, they will be in violation of the law and dealt with as criminals. We are in full support with the struggle of the Palestinian people for liberation of Palestine from Zionist colonialism, and their goals of creating a democratic state where all Palestinians, Jews, Christians and Moslems are equal. We propose solidarity with the liberation struggle of the Puerto Rican people, who now exist as a colony of the United States and have many -

Black Capitalism Re-Analyzed I: June 5, 1971 Huey Newton

““We want an end to the robbery by the CAPITALISTS of our Black Community.” That was our position in October 1966 and it is still our position… However, many people have offered the community Black capitalism as a solution to our problems. We recognize that people in the Black community have no general dislike for the concept of Black capitalism, but this is not because they are in love with capitalism. Not at all.” A small collection of writings on what Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, called Black Capitalism. BLACK CAPITALISM RE-ANALYZED I: JUNE 5, 1971 HUEY NEWTON The Black Panther Party, as we begin to carry out the original vision of the Party. When we coined the expression “All Power to the People,” we had in mind emphasizing the word “Power,” for we recognize that the will to power is the basic drive of man. But it is incorrect to seek power over people. We have been subjected to the dehumanizing power of exploitation and racism for hundreds of years; and the Black community has its own will to power also. What we seek, however, is not power over people, but the power to control our own destiny. For us the true definition of power is not in terms of how many people you can control. To us power is, first of all, the ability to define phenomena, and secondly the ability to make these phenomena act in a desired manner. We see then that power has a dual character and that we cannot simply identify and define phenomena without acting, for to do so is to become an armchair philosopher. -

All Power to the People: the Black Panther Party As the Vanguard of the Oppressed

ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE: THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AS THE VANGUARD OF THE OPPRESSED by Matthew Berman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Wilkes Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a Concentration in American Studies Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University Jupiter, Florida May 2008 ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE: THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AS THE VANGUARD OF THE OPPRESSED by Matthew Berman This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor, Dr. Christopher Strain, and has been approved by the members of her/his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Honors College and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ____________________________ Dr. Christopher Strain ____________________________ Dr. Laura Barrett ______________________________ Dean, Wilkes Honors College ____________ Date ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Author would like to thank (in no particular order) Andrew, Linda, Kathy, Barbara, and Ronald Berman, Mick and Julie Grossman, the 213rd, Graham and Megan Whitaker, Zach Burks, Shawn Beard, Jared Reilly, Ian “Easy” Depagnier, Dr. Strain, and Dr. Barrett for all of their support. I would also like to thank Bobby Seale, Fred Hampton, Huey Newton, and others for their inspiration. Thanks are also due to all those who gave of themselves in the struggle for showing us the way. “Never doubt that a small group of people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” – Margaret Mead iii ABSTRACT Author: Matthew Berman Title: All Power to the People: The Black Panther Party as the Vanguard of the Oppressed Institution: Wilkes Honors College at Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. -

History of the Black Panther Party—Part

Handout 1: History of the Black Panther Party—Part The Black Panther Party One Legacy and Lessons for the What Was the Black Panther Party? Future The Black Panther Party (BPP) was a progressive political organization that stood in the vanguard of the most powerful movement for social change in America since the Revolution of 1776 and the Civil War: that dynamic episode generally referred to as The Sixties. It is the sole Black organization in the entire history of Black struggle against slavery and oppression in the United States that was armed and promoted a revolutionary agenda, and it represents the last great thrust by the masses of Black people for equality, justice, and freedom. The Party’s ideals and activities were so radical that it was at one time labeled by FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover as “the greatest threat to the internal security of the United States.” And despite the demise of the Party, its history and lessons remain so challenging and controversial that established texts and media erase all reference to the Party from their portrayals of American history. The Black Panther Party was the manifestation of the vision of Huey P. Newton, the seventh son of a Louisiana family transplanted to Oakland, California. In the wake of the assassination of Black leader Malcolm X, on the heels of the massive Black, urban uprising in Watts, California, and at the height of the Civil Rights Movement led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in October of 1966, Newton gathered a few of his longtime friends, including Bobby Seale and David Hilliard, and developed a skeletal outline for this organization. -

Her Name Is Assata! by ZAYID MUHAMMAD

DAILY CHALLENGE WEDNESDAY, JULY 25, 2001 Her name is Assata! allowed for the most disconnected By ZAYID MUHAMMAD and disaffected of our youth at that time to enter onto the stage of histo- Sir, ry as revolutionary agents of Her name is Assata!... change, and as perhaps the boldest Although her enemies and example of attempting to implement Malcolm's line in the teeming slums the enemies of our people of this country's upsouth northern insist on calling her "the noto- cities... rious cop killer Joanne Chesi- It was a part of the New York mard" as they continue to chapter of the party that she became demonize her, her name is a 'Shakur,'...along with other fear- less Panthers from those ranks like Assata. Afeni Shakur, Tupac's mom, like To be sure, it is actually Lumumba Shakur, a brother who Assata Olubala Shakur or "she got things done and wore his dred- who struggles, loves her peo- locks with regal ease way before ple and is grateful." they 'got in style,' like a young She has indeed proven herself to Mutulu Shakur, who later become be most grateful for the bravest of Dr. Mutulu Shakur, a pioneering our ancestors who have gone on acupuncturist who used this content before us; for the strength of her tradition to get people clean, and family, especially her grandparents who is now one of our political pris- who taught her from the time that oners and like Zayd Shakur, a she was a child how to stand up to resourceful organizer who tragically racists; for having had comrades did not survive 'the Turnpike Mas- who were heroically rich in courage; sacre'...worked hard making the and for the compassion, love and Party's example of a socialist alter- unconditional support of those who native within a racist and capitalist helped her on her way along those paradigm that cared nothing about blazing trails of the underground. -

The Evolution of (Black) Communal Socialism103 K

The Evolution of (Black) Communal Socialism103 K. Kim Holder and Joy James You have to go back and reach out to your neighbors who don’t speak to you! And you have to reach out to your friends . get them to understand that they, as well as you and I, cannot be free in America, or anywhere else, where there is capitalism. .”—Ella Baker, Ella Baker Speaks! (1974)104 We live in strange times. We have a black president using race-neutral framing for social justice, alongside a Black Lives Matter movement using structural racism framing for participa- tory democracy. Killer Mike, a Southern rapper best known for his work with the Grammy Award-winning superduo Outkast, has endorsed a sitting U.S. senator and self-described socialist, Bernie Sanders. Some black preachers, apparently, are trip- ping over themselves to cozy up to Donald Trump or reposition themselves within the arc of Hillary Clinton’s historic candidacy. Strange times indeed.—Rev. Andrew J. Wilkes, January 14, 2016105 I. INTRODUCTION There are varied approaches to understanding democratic socialism (DS). A concept for politics used by progressives, workers, academics, anti-rac- ists, feminists, queer activists and elected ofcials. Using the language 103 This chapter is developed from chapter 4 of Kit Kim Holder, “History of the Black Panther Party, 1966-1972: A Curriculum Tool for African-American Stud- ies” (UMass-Amherst, dissertation, May 1990). 104 http://writingcities.com/2017/12/15/ella-baker-puerto-rico-solidarity-rally-1974/. 105 https://www.religioussocialism.org/socialism_in_black_america. -

It's About Time…

It’s About Time… Volume 5 Number 3 Summer 2001 OUR SAN FRANCISCO KID News Briefs PASSES ON Houston - Shaka Sankofa’s son, Gary Lee Hawkins, convicted of Black Panther Captain Warren Wells murder - gets life. He was accused of robbing and killing a friend, but Remembered as the People’s Defender maintains his innocence. York, PA - A new autopsy has been performed on the exhumed body By Ida McCray and Kiilu Nyasha of a white police officer shot to death during the city’s 1969 riots. The Warren William Wells was born in San Francisco’s Alice Griffith body of Henry C. Schaad was exhumed Tuesday morning, looking for projects (Double Rock) on Nov. 13, 1947. His first struggle in a predomi- metallic remnants and a few were found. Prosecutors are reinvestigating nately Black community was to over- the killings of Schaad and Lillie Belle Allen, an African American woman, come the stigma attached to his green both shot during 10 days of riots in July 1969. Nine white men, including eyes and light skin. Nicknamed York Mayor Charlie Robertson, were recently charged with homicide in “Dub”, Warren got his first taste of the Allen shooting. prison in 1963, when at the tender age Oklahoma City - Police took blood from 200 men and compared of 16, he was sentenced as an adult to their DNA to the semen left behind in a murdered woman’s car in a “sweep” Soledad State Prison. It was there that for DNA. There were no matches. Police plan to test 200 more men who he met brothers like George Jackson, either lived near the victim and have a criminal record or resemble the Eldridge Cleaver, Alprentice Bunchy police sketch. -

COINTELPRO: the Untold American Story

COINTELPRO: The Untold American Story By Paul Wolf with contributions from Robert Boyle, Bob Brown, Tom Burghardt, Noam Chomsky, Ward Churchill, Kathleen Cleaver, Bruce Ellison, Cynthia McKinney, Nkechi Taifa, Laura Whitehorn, Nicholas Wilson, and Howard Zinn. Presented to U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Mary Robinson at the World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa by the members of the Congressional Black Caucus attending the conference: Donna Christianson, John Conyers, Eddie Bernice Johnson, Barbara Lee, Sheila Jackson Lee, Cynthia McKinney, and Diane Watson, September 1, 2001. Table of Contents Overview Victimization COINTELPRO Techniques Murder and Assassination Agents Provocateurs The Ku Klux Klan The Secret Army Organization Snitch Jacketing The Subversion of the Press Political Prisoners Leonard Peltier Mumia Abu Jamal Geronimo ji Jaga Pratt Dhoruba Bin Wahad Marshall Eddie Conway Justice Hangs in the Balance Appendix: The Legacy of COINTELPRO CISPES The Judi Bari Bombing Bibliography Overview We're here to talk about the FBI and U.S. democracy because here we have this peculiar situation that we live in a democratic country - everybody knows that, everybody says it, it's repeated, it's dinned into our ears a thousand times, you grow up, you pledge allegiance, you salute the flag, you hail democracy, you look at the totalitarian states, you read the history of tyrannies, and here is the beacon light of democracy. And, of course, there's some truth to that. There are things you can do in the United States that you can't do many other places without being put in jail. But the United States is a very complex system. -

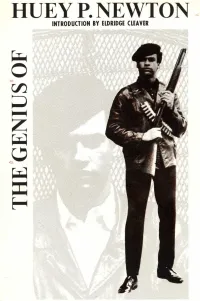

Huey P. Newton Introduction by Eldridge Cleaver

HUEY P. NEWTON INTRODUCTION BY ELDRIDGE CLEAVER rs.~ O W W Hx THE GENIUS OF I UEY P NEWTON CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... HUEY P. NEW'T'ON TO THE REPUBLIC OF NEW AFRICA. ... .. .. .. 8 MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER OF DEFENSE, HUEY P . NEWTON ON THE PEACE MOVEMENT .. .. 12 PRISON, WHERE IS THY VICTORY? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... .. .18 HUEY (NEWTON TALKS TO THE MOVEMENT.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..022 FUNCTIONAL DEFINITION OF POLITICS.,. .. .. .. .. ... .. ..w. .. .. .26 THE GENIUS OF HUEY P. NEWTON .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .... .. .. ..30 TEN POINT PLATFORM and PROGRAM. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 38 This Is The Introduction To The New Volume Of Essays Of The Minister Of Defense Huey P, Newton's thoughts, like his action is clear and precise . cutting always to the very heart of the matter. Huey's genius is that he took up where brother Malcolm left off when he was assassinated. Huey was successful in creating an organization unique in the history of Afro-Americans . A revolutionary political party with self perpetuating machinery. This is an historic achievement. And it is the thought of Huey P. Newton that holds the Black Panther Party together and constitutes its foundation. Huey was always conscious of the fact that he was creating a vanguard organization, and that he was mov- ing at a speed so far beyond where the rest of Afro America was at, that his primary concern was to find ways of rapidly communicating what he saw and knew to the rest of the people. This was always Huey"s major concern to insure that the people received correct information. He had an unshakable faith in the ability of the people to make the correct decisions once they received accurate information. -

A Look Inside the Political Hip Hop Music of Tupac Amaru Shakur

ABSTRACT AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES, AFRICANA WOMEN’S STUDIES, AND HISTORY WATKINS, TRINAE M.A. CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY, 2018 PANTHER POWER: A LOOK INSIDE THE POLITICAL HIP HOP MUSIC OF TUPAC AMARU SHAKUR Committee Chair: Charmayne Patterson, Ph.D. Thesis dated December 2018 In this study, seven rap songs by hip hop icon Tupac Shakur were examined to determine if the ideology of the Black Panther Party exists within the song lyrics of his politically oriented music. The study used content analysis as its methodology. Key among the Ten Point Program tenets reflected in Tupac’s song lyrics were for self- determination, full employment, ending exploitation of Blacks by Whites (or Capitalists), decent housing, police brutality, education, liberation of Black prisoners, and the demand for land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, peace, and a United Nations plebiscite. PANTHER POWER: A LOOK INSIDE THE POLITICAL HIP HOP MUSIC OF TUPAC AMARU SHAKUR A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY TRINAE WATKINS DEPARTMENT OF AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES, AFRICANA WOMEN’S STUDIES, AND HISTORY ATLANTA, GEORGIA DECEMBER 2018 © 2018 TRINAE WATKINS All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I give all praises and honor to the Most High, the Eternal Elohim and Creator. I offer gratitude and sincere thanks to my grandparents and the wonderful ancestors that preceded them; my loving parents, Perry and Augustae Watkins; my forever supportive extended family from both the Watkins and Jones family lineages as well as childhood friends, Debbie Cooper and Dr. Sandra Cutts. -

The Influence and Legacy of the Black Panther Party, 1966 – 1980

“All Power to the People”: The Influence and Legacy of the Black Panther Party, 1966 – 1980 by Lisa Vario Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master’s of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY December, 2007 “All Power to the People”: The Influence and Legacy of the Black Panther Party, 1966 – 1980 Lisa Vario I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ________________________________________________________________ Lisa Vario, Student Date Approvals: ________________________________________________________________ Anne York, Thesis Advisor Date ________________________________________________________________ David Simonelli, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________________ Donna DeBlasio, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean of School of Graduate Studies & Research Date Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………….... iv Abstract…………………………………………………………………………..… 1 Introduction: “Educate the Masses”……………………………………………....... 2 Chapter One: “The Roots of the American Black Power Movement”…………… 9 Chapter Two: “The Black Panther Party: 1966 – 1973”……………………..…… 21 Chapter Three: “The Black Panther Party: