Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Novembre 2012 Nouveautés – New Arrivals November 2012

Novembre 2012 Nouveautés – New Arrivals November 2012 ISBN: 9781551119342 (pbk.) ISBN: 155111934X (pbk.) Auteur: Daly, Chris. Titre: An introduction to philosophical methods / Chris Daly. Éditeur: Peterborough, Ont. : Broadview Press, c2010. Desc. matérielle: 257 p. ; 23 cm. Collection: (Broadview guides to philosophy.) Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographical references (p. 223-247) and index. B 53 D34 2010 ISBN: 9780813344485 (pbk. : alk. paper) $50.00 ISBN: 0813344484 (pbk. : alk. paper) Auteur: Boylan, Michael, 1952- Titre: Philosophy : an innovative introduction : fictive narrative, primary texts, and responsive writing / Michael Boylan, Charles Johnson. Éditeur: Boulder, CO : Westview Press, c2010. Desc. matérielle: xxii, 344 p. ; 24 cm. Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographical references and index. B 74 B69 2010 ISBN: 9783034311311 (pbk.) $108.00 ISBN: 3034311311 (pbk.) Titre: Understanding human experience : reason and faith / Francesco Botturi (ed.). Éditeur: Bern ; New York : P. Lang, c2012. Desc. matérielle: 197 p. ; 23 cm. Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographical references. B 105 E9U54 2012 ISBN: 9782706709104 (br) ISBN: 2706709103 (br) Auteur: Held, Klaus, 1936- Titre: Voyage au pays des philosophes : rendez-vous chez Platon / Klaus Held ; traduction de l'allemand par Robert Kremer et Marie-Lys Wilwerth-Guitard. Éditeur: Paris : Salvator, 2012. Desc. matérielle: 573 p. : ill., cartes ; 19 cm. Note générale: Traduction de: Treffpunkt Platon. Note générale: Première éd.: 1990. Note bibliogr.: Comprend des références bibliographiques (p. 547-558) et des index. B 173 H45T74F7 2012 ISBN: 9780826457530 (hbk.) ISBN: 0826457533 (hbk.) Auteur: Adluri, Vishwa. Titre: Parmenides, Plato, and mortal philosophy : return from transcendence / Vishwa Adluri. Éditeur: London ; New York : Continuum, c2011. Desc. matérielle: xv, 212 p. ; 24 cm. Collection: (Continuum studies in ancient philosophy) Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographical references (p. -

1 FIFTH WORLD CONGRESS for the PASTORAL CARE of MIGRANTS and REFUGEES Presentation of the Fifth World Congress for the Pastoral

1 FIFTH WORLD CONGRESS FOR THE PASTORAL CARE OF MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES Presentation of the Fifth World Congress for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees Address of Pope John Paul II Address of H.E. Stephen Fumio Cardinal Hamao to His Holiness Pope John Paul II Welcome Address, Card. Stephen Fumio Hamao Presentation of the Congress, Card. Stephen Fumio Hamao The Present Situation of International Migration World-Wide, Dr. Gabriela Rodríguez Pizarro Refugees and International Migration. Analysis and Action Proposals, Prof. Stefano Zamagni The Situation and Challenges of the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees in Asia and the Pacific, Bishop Leon Tharmaraj The Situation and Challenges of the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees in North America, Rev. Anthony Mcguire Migrants and Refugees in Latin America, Msgr. Jacyr Francisco Braido, CS Situation and Challenges regarding the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees in Africa. Comments by a Witness and “Practitioner”, Abraham-Roch Okoku-Esseau, S.J. Situations and Challenges for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees in Europe, Msgr. Aldo Giordano Starting afresh from Christ. The Vision of the Church on Migrants and Refugees. (From Post- Vatican II till Today), H.E. Archbishop Agostino Marchetto Starting afresh from Christ. The Vision of the Church for a Multicultural/Intercultural Society, H.E. Cardinal Paul Poupard Starting afresh from Christ. The Vision and the Guidelines of the Church for Ecumenical Dialogue, Card. Walter Kasper Starting afresh from Christ. The Vision and Guidelines of the Church for Inter-Religious Dialogue, Archbishop Pier Luigi Celata The Anglican Communion, His Grace Ian George 2 World Council of Churches, Ms Doris Peschke The German Catholic Church’s Experience of Ecumenical Collaboration in its Work with Migrants and Refugees, Dr. -

Copyright © 2016 Matthew Habib Emadi All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2016 Matthew Habib Emadi All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE ROYAL PRIEST: PSALM 110 IN BIBLICAL- THEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Matthew Habib Emadi May 2016 APPROVAL SHEET THE ROYAL PRIEST: PSALM 110 IN BIBLICAL- THEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE Matthew Habib Emadi Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ James M. Hamilton (Chair) __________________________________________ Peter J. Gentry __________________________________________ Brian J. Vickers Date______________________________ To my wife, Brittany, who is wonderfully patient, encouraging, faithful, and loving To our children, Elijah, Jeremiah, Aliyah, and Josiah, may you be as a kingdom and priests to our God (Rev 5:10) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................ ix LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ xii PREFACE ........................................................................................................................ xiii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

Drei Worte Für Unser Leben: Schauen, Anfassen, Essen

UNICUIQUE SUUM NON PRAEVALEBUNT Redaktion: I-00120 Vatikanstadt Schwabenverlag AG Einzelpreis Wochenausgabe in deutscher Sprache 51. Jahrgang – Nummer 16 – 23. April 2021 D-73745 Ostfildern Vatikan d 2,20 Ansprache von Papst Franziskus beim Regina Caeli am dritten Sonntag der Osterzeit, 18. April Drei Worte für unser Leben: schauen, anfassen, essen Lieber Brüder und Schwestern, um die Eucharistie vor der Profanierung zu schüt- guten Tag! zen. Möge ihr Beispiel uns zu einem größeren Einsatz in der Treue zu Gott anspornen, der auch An diesem dritten Sonntag der Osterzeit keh- in der Lage ist, die Gesellschaft zu verändern und ren wir nach Jerusalem zurück, in den Abend- sie gerechter und brüderlicher zu machen. Ein mahlssaal, wie die beiden Emmausjünger, die auf Applaus für die neuen Seligen! dem Weg den Worten Jesu mit großer Ergriffen- Und das ist traurig: Ich verfolge mit großer heit zugehört und ihn dann, »als er das Brot Sorge die Ereignisse in einigen Gebieten der brach« (Lk 24,35), erkannt hatten. Jetzt, im Ostukraine, wo sich die Verstöße gegen die Waf- Abendmahlssaal, erscheint der auferstandene fenruhe in den letzten Monaten vervielfacht ha- Christus inmitten der Gruppe der Jünger und ben, und ich nehme mit großer Sorge die Zu- grüßt sie: »Friede sei mit euch!« (V. 36). Aber sie nahme der militärischen Aktivitäten zur erschrecken und meinen, »einen Geist zu sehen«, Kenntnis. Bitte, ich hoffe sehr, dass die Zunahme wie es im Evangelium heißt (V. 37). Dann zeigt Je- der Spannungen vermieden wird und dass im sus ihnen die Wunden an seinem Leib und sagt: Gegenteil Zeichen gesetzt werden, die das ge- »Seht meine Hände und meine Füße an«, die genseitige Vertrauen fördern und die Versöhnung Wunden: »Ich bin es selbst. -

The Controversy Surrounding the 2008 Good Friday Prayer in Europe: the Discussion and Its Theological Implications 11.09.2009 | Henrix, Hans Hermann

Jewish-Christian Relations Insights and Issues in the ongoing Jewish-Christian Dialogue The Controversy Surrounding the 2008 Good Friday Prayer in Europe: The Discussion and its Theological Implications 11.09.2009 | Henrix, Hans Hermann With courtesy of The Council of Centers on Jewish-Christian Relations, United States/Canada The Controversy Surrounding the 2008 Good Friday Prayer in Europe: The Discussion and its Theological Implications* Hans Hermann Henrix Good Friday of the year 2008 has a unique place in the history of Catholic-Jewish relations. The Good Friday prayer “for the Jews” that was promulgated by Pope Benedict XVI and published in a note from the Secretariat of State on February 4, 2008 triggered significant controversy affecting Catholic-Jewish relations. The 2008 text of the intercession reads: Let us pray for the Jews. That our God and Lord enlighten their hearts so that they recognize Jesus Christ, the Savior of all mankind. Let us pray. Let us kneel down. Arise. Eternal God Almighty, you want all people to be saved and to arrive at the knowledge of the Truth. Graciously grant that when the fullness of nations enters your Church, all Israel will be saved. Through Christ our Lord.1 Both the way the publication and communication were handled and the theological implications of the intercession generated this controversy. This article records the basic themes of the European discussion on this matter, reporting on the political dialogue accompanying the controversy. It will also raise questions about whether the 2008 Good Friday prayer should be understood as an opening for further Catholic liturgical changes and about whether requests for Jewish reciprocity liturgically are relevant. -

The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 44 EDITORIAL BOARD Mark S

The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 44 EDITORIAL BOARD Mark S. Smith, Chairperson Lawrence E. Boadt, C.S.P. Richard J. Clifford, S.J. John J. Collins Frederick W. Danker Robert A. Di Vito Daniel J. Harrington, S.J. Ralph W. Klein Léo Laberge, O.M.I. Bruce J. Malina Pheme Perkins Eugene C. Ulrich Ronald D. Witherup, S.S. Studies in the Greek Bible Essays in Honor of Francis T. Gignac, S.J. EDITED BY Jeremy Corley and Vincent Skemp The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 44 © 2008 The Catholic Biblical Association of America, Washington, DC 20064 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Catholic Biblical Association of America. Produced in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Studies in the Greek Bible : essays in honor of Francis T. Gignac, S.J. / edited by Jeremy Corley and Vincent Skemp. p. cm. — (The Catholic biblical quarterly monograph series ; 44) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0-915170-43-4 (alk. paper) 1. Bible. Greek—Versions—Septuagint. 2. Bible—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. Gignac, Francis T. II. Corley, Jeremy. III. Skemp, Vincent T. M. BS38.S78 2008 220.6—dc22 2008026572 Contents FOREWORD Alexander A. Di Lella, O.F.M. ix INTRODUCTION Jeremy Corley and Vincent Skemp, editors xiii PART ONE GENESIS CREATION TRADITIONS 1 CREATION UNDER CONTROL: POWER LANGUAGE IN GENESIS :–: Jennifer M. Dines 3 GUARDING HEAD AND HEEL: OBSERVATIONS ON SEPTUAGINT GENESIS : C. T. Robert Hayward 17 “WHAT IS epifere?” GENESIS :B IN THE SAHIDIC VERSION OF THE LXX AND THE APOCRYPHON OF JOHN Janet Timbie 35 v vi · Contents PART TWO LATER SEPTUAGINTAL BOOKS 47 A TEXTUAL AND LITERARY ANALYSIS OF THE SONG OF THE THREE JEWS IN GREEK DANIEL :- Alexander A. -

VADE ET TU FAC SIMILITER: from HIPPOCRATES to the GOOD SAMARITAN 69 AIDS As a Disease of the Body and the Spirit the Hippocratic Oath Robert C

Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference organized by the Pontifical Council DOLENTIUM HOMINUM for Pastoral Assistance No. 31 (Year XI - No.1) 1996 JOURNAL OF THE to Health Care Workers PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR PASTORAL ASSISTANCE TO HEALTH CARE WORKERS Editorial Board: FIORENZO Cardinal ANGELINI, Editor Rev. JOSÉ L. REDRADO O.H., Managing Editor Rev. FELICE RUFFINI M.I., Associate Editor Rev. GIOVANNI D’ERCOLE F.D.P. Vade et Tu Sr. CATHERINE DWYER M.M.M. Dr. GIOVANNI FALLANI Msgr. JESUS IRIGOYEN Rev. VITO MAGNO R.C.I. Fac Similiter: Ing. FRANCO PLACIDI Prof. GOTTFRIED ROTH From Hippocrates Msgr. ITALO TADDEI To the Good Editorial Staff: Rev. DAVID MURRAY M.ID. Samaritan MARIA ÁNGELES CABANA M.ID. Sr. M. GABRIELLE MULTIER Rev. JEAN-MARIE M. MPENDAWATU Editorial and Business Offices: Vatican City Telephone: 6988-3138, November 23-24-25, 6988-4720, 6988-4799, Telefax: 6988-3139 1995 Telex: 2031 SANITPC VA In copertina: glass-window P. Costantino Ruggeri Published three times a year: Subscription rate: one year Lire 60.000 (abroad or the corresponding amount in local currency, postage included). The price of this special issue is Lire 80,000 ($ 80) Printed by Editrice VELAR S.p.A., Gorle (BG) Paul VI Hall Vatican City Spedizione in abbonamento postale 50% Roma Contents 6 A Man Went Down to Jericho 42 Hippocrates in the Documents of the Greeting Addressed to the Holy Father Church and in Works of Theology by Cardinal Fiorenzo Angelini Gottfried Roth 7 Address by the 45 The Care of the Sick Holy Father in the History of the Church John -

Ministerial Priesthood in the Third Millennium

Ministerial Priesthood in the Third Millennium Ministerial Priesthood in the Third Millennium Faithfulness of Christ, Faithfulness of Priests LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Cover design by Ann Blattner. Excerpts from the English translation of Rite of Baptism for Children © 1969, International Committee on English in the Liturgy, Inc. (ICEL); excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal © 1973, ICEL; excerpt from the English translation of Rite of Penance © 1974, ICEL. All rights reserved. Excerpts from the English translation of The Ordination of Deacons, Priests, and Bishops © 1975, International Committee on English in the Liturgy, Inc. (ICEL); excerpt from the English translation of Rites of Ordination of a Bishop, of Priests, and of Deacons © 2000, 2002, ICEL. All rights reserved. © 2009 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights re- served. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 23456789 ISBN 978-0-8146-3326-7 Contents List of Contributors vii Introduction xi Monsignor Kevin W. Irwin CHAPTER 1 The Biblical Foundations of the Priesthood: The Contribution of Hebrews 1 Very Rev. Ronald D. Witherup, SS CHAPTER 2 Living Sacraments: Some Reflections on Priesthood in Light of the French School and Documents of the Magisterium 24 Very Rev. Lawrence B. Terrien, SS CHAPTER 3 “Faithful Stewards of God’s Mysteries”: Theological Insights on Priesthood from the Ordination Ritual 43 Rev. -

Biblical Ethics 565290Research-Article2014

TSJ0010.1177/0040563914565290Theological StudiesBiblical Ethics 565290research-article2014 Article Theological Studies 2015, Vol. 76(1) 112 –128 NOTES ON MORAL THEOLOGY © Theological Studies, Inc. 2015 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Biblical Ethics: 3D DOI: 10.1177/0040563914565290 tsj.sagepub.com Lúcás Chan, S.J. Marquette University, USA Abstract The past two decades have seen significant developments in the field of biblical ethics. The article looks at these in three dimensions so as to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the efforts of biblical scholars and Christian ethicists. The author perceives that a more integrated approach to biblical ethics, collaboration on various levels, innovation in our approaches, and humble learning from our colleagues worldwide can throw light on our search for future direction in the field. Keywords Bible, Bible and ethics, Bible and morality, biblical ethics, Christian ethics, globalization and ethics, morality, Scripture and ethics, Scripture and morality, scriptural ethics, theological ethics, virtue ethics wo questions need to be raised at the outset: What is biblical ethics, and what does “3D” in the title stand for? The first question is better rephrased as, What is hap- Tpening in the field of biblical ethics?1 Although using Scripture as the sole author- ity for Christian ethics has for centuries distinguished Protestant from Catholic methodology, biblical ethics is not a new area of research within the Roman Catholic 1. My survey focuses on developments in New Testament ethics over the past two decades. Though I write as a Catholic biblical ethicist, I consider both Catholic and Protestant contributions. Corresponding author: Lúcás Chan, S.J. -

View PDF Version

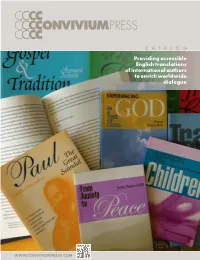

CATALO G Providing accessible English translations of international authors to enrich worldwide dialogue WWW.CONVIVIUMPRESS.COM INDEX Page 5 | Exploring Faith with New Eyes 6 | A Prophetic Bishop Speaks to His People. The Complete Homilies of Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero (Vol. 1, 2 & 3) 8 | A Study Guide on the Reign of God 9 | For Love or Money: Rampant Capitalism an the Praxis of Jesus | A Face for God. Reflections on Trinitarian Theology for our Times 10 | The Way Opened Up by Jesus: A Commentary on the Gospel of Mark | Words of Liberty: The Biblical Message of Liberation 11 | From Anxiety to Peace | The Prayer that Jesus Taught 12 | Meditation with Children | Believe? Tell Me Why: Conversations with Those Who Have Left the Church 13 | Forgive Yourself | Persons Are Our Best Gifts 14 | The Living and True God. The Mystery of the Trinity | Gospel & Tradition 15 | Jesus: An Historical Approximation 16 | Jesus Christ: Salvation of All | God’s Reign & the End of Empires 17 | Morality in Social Life | Called to Freedom 18 | A New Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels | A Different Priest: The Epistle to the Hebrews 19 | The Way Opened Up by Jesus: A Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew | Paul: The Great Scandal 20 | The Banquet: A Reading of the Fifth Sura of the Qur’an | Builders of Community. Rethinking Ecclesiastical Ministry 21 | Hispanic Ministry in the 21 st Century: Present and Future 22 | Following in the Footsteps of Jesus. Years A, B & C 23 | The Art of Purifying the Heart | Transparencies of Eternity 24 | The Goal of Life | Why Are We Here? | Experiencing God in a Time of Crisis ©Sergio Cuesta. -

Pontificia Academia Theologica - 2003/2

RIVISTA NOVEMBRE 2003 9-01-2004 15:25 Pagina 269 PATH VOL. 2 - PONTIFICIA ACADEMIA THEOLOGICA - 2003/2 Cristologia tra questioni e prospettive 271-276 Editoriale Piero Coda 277-304 Cristocentrismo: significato e valenza teologica oggi Paolo Scarafoni 305-320 I fondamenti della cristologia neotestamentaria Alcuni aspetti della questione Romano Penna 321-340 La recente interpretazione della definizione di Calcedonia Luis F. Ladaria 341-374 Logos and Tao: Johannine christology and a taoist perspective Joseph H. Wong 375-399 L’universalità della salvezza in Cristo e le mediazioni partecipate Marcello Bordoni 401-415 La fede di Gesù? A proposito di Ebrei 12,2: «Gesù, autore e perfezionatore della fede» Albert Vanhoye 417-441 Le mystère de l’agonie de Jesus à la lumiere de la théologie des Saints François-Marie Léthel 443-471 «Disagi» contemporanei di fronte al paradosso cristiano dell’incarnazione Nicola Ciola 473-490 Le christocentrisme, lieu d’émergence d’une morale du maximum. Reflexions à la lumiere du IVe évangile Réal Tremblay RIVISTA NOVEMBRE 2003 9-01-2004 15:25 Pagina 270 491-504 «Io vado a prepararvi un posto» (Gv 14,2). Riflessioni sulla dialettica simbolica o di unità dei distinti della cri- stologia con l’escatologia Giorgio Gozzelino 505-525 Cristologia e spiritualità Vincenzo Battaglia RECENSIONES G. Canobbio - P. Coda (edd.), La teologia del XX secolo. Un bilancio, 3 voll., Città Nuova, Roma 2003, pp. 527-529. VITA ACADEMIAE 1. Nomina del Prelato Segretario, p. 531. 2. Cronaca dell’Accademia, p. 531-532. OPERA ACCEPTA, pp. 533-534. INDEX TOTIUS VOLUMINIS, pp. 535-536 RIVISTA NOVEMBRE 2003 9-01-2004 15:25 Pagina 271 EDITORIALE PATH 2 (2003) 271-276 “Ripartire da Cristo!”. -

PDF Download a Different Priest: the Epistle to the Hebrews Pdf

A DIFFERENT PRIEST: THE EPISTLE TO THE HEBREWS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Albert Vanhoye | 454 pages | 27 Mar 2011 | Convivium Press | 9781934996201 | English | Miami, FL, United States A Different Priest: The Epistle to the Hebrews - Albert Vanhoye - Google книги He must be intensively trained in all of the ceremonial practices of priesthood and elaborately initiated into the ranks of priests. Priests belong to an order of priesthood and are associated with a sanctuary. The author of this epistle appeals to the Aaronic priesthood as the very highest expression of professional priesthood that he knows. If any priesthood could have been expected to fulfil successfully the functions of priesthood, this priesthood should have been expected to do so in his judgment, for it was instituted by God himself. He uses this priesthood as a medium of comparison for the priesthood of Jesus, and because of the familiarity of his readers with it, as a means of explaining to them the nature of Jesus' priesthood. He is highly appreciative of the Aaronic priesthood and exalts it in order to exalt even more the priesthood of Jesus which he claims is better than it. Despite his high regard for the Aaronic priesthood, the author believes that it has failed to achieve the real purposes of priesthood and the true ends of religion. Its two chief failures are failure to remove the obstacles, hindrances, and hurdles which separate men from God, particularly men's sins, and failure to gain access for men to God. From the emphasis which the author lays on these two failures, it follows that he believes that true and successful priesthood must fulfil these two functions.