11-20 How Magicians OTP 2P.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biblioteca Digital De Cartomagia, Ilusionismo Y Prestidigitación

Biblioteca-Videoteca digital, cartomagia, ilusionismo, prestidigitación, juego de azar, Antonio Valero Perea. BIBLIOTECA / VIDEOTECA INDICE DE OBRAS POR TEMAS Adivinanzas-puzzles -- Magia anatómica Arte referido a los naipes -- Magia callejera -- Música -- Magia científica -- Pintura -- Matemagia Biografías de magos, tahúres y jugadores -- Magia cómica Cartomagia -- Magia con animales -- Barajas ordenadas -- Magia de lo extraño -- Cartomagia clásica -- Magia general -- Cartomagia matemática -- Magia infantil -- Cartomagia moderna -- Magia con papel -- Efectos -- Magia de escenario -- Mezclas -- Magia con fuego -- Principios matemáticos de cartomagia -- Magia levitación -- Taller cartomagia -- Magia negra -- Varios cartomagia -- Magia en idioma ruso Casino -- Magia restaurante -- Mezclas casino -- Revistas de magia -- Revistas casinos -- Técnicas escénicas Cerillas -- Teoría mágica Charla y dibujo Malabarismo Criptografía Mentalismo Globoflexia -- Cold reading Juego de azar en general -- Hipnosis -- Catálogos juego de azar -- Mind reading -- Economía del juego de azar -- Pseudohipnosis -- Historia del juego y de los naipes Origami -- Legislación sobre juego de azar Patentes relativas al juego y a la magia -- Legislación Casinos Programación -- Leyes del estado sobre juego Prestidigitación -- Informes sobre juego CNJ -- Anillas -- Informes sobre juego de azar -- Billetes -- Policial -- Bolas -- Ludopatía -- Botellas -- Sistemas de juego -- Cigarrillos -- Sociología del juego de azar -- Cubiletes -- Teoria de juegos -- Cuerdas -- Probabilidad -

Attention and Awareness in Stage Magic: Turning Tricks Into Research

PERSPECTIVES involve higher-level cognitive functions, SCIENCE AND SOCIETY such as attention and causal inference (most coin and card tricks used by magicians fall Attention and awareness in stage into this category). The application of all these devices by magic: turning tricks into research the expert magician gives the impression of a ‘magical’ event that is impossible in the physical realm (see TABLE 1 for a classifica- Stephen L. Macknik, Mac King, James Randi, Apollo Robbins, Teller, tion of the main types of magic effects and John Thompson and Susana Martinez-Conde their underlying methods). This Perspective addresses how cognitive and visual illusions Abstract | Just as vision scientists study visual art and illusions to elucidate the are applied in magic, and their underlying workings of the visual system, so too can cognitive scientists study cognitive neural mechanisms. We also discuss some of illusions to elucidate the underpinnings of cognition. Magic shows are a the principles that have been developed by manifestation of accomplished magic performers’ deep intuition for and magicians and pickpockets throughout the understanding of human attention and awareness. By studying magicians and their centuries to manipulate awareness and atten- tion, as well as their potential applications techniques, neuroscientists can learn powerful methods to manipulate attention to research, especially in the study of the and awareness in the laboratory. Such methods could be exploited to directly study brain mechanisms that underlie attention the behavioural and neural basis of consciousness itself, for instance through the and awareness. This Perspective therefore use of brain imaging and other neural recording techniques. seeks to inform the cognitive neuroscientist that the techniques used by magicians can be powerful and robust tools to take to the Magic is one of the oldest and most wide- powers. -

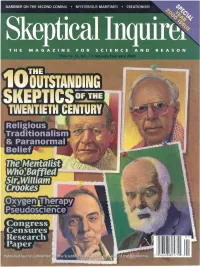

Here Are Many Heroes of the Skeptical Movement, Past and Present

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONA! (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist. York Univ., Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Univ. Dorothy Nelkin, sociologist, New York Univ. Toronto Henry Gordon, magician, columnist, Joe Nickell,* senior research fellow, CSICOP Steve Allen, comedian, author, composer, Toronto Lee Nisbet* philosopher, Medaille College pianist Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Bill Nye, science educator and television Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. host, Nye Labs Albany, Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts James E. Oberg, science writer Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, Loren Pankratz, psychologist Oregon Kentucky University of Miami Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist Univ. of Wales Health Sciences Univ. consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein, * biopsychologist, Simon Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human W. V. Quine, philosopher, Harvard Univ. Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada understanding and cognitive science, Milton Rosenberg, psychologist. Univ. of Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Indiana Univ. Chicago Southern California Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor Susan Blackmore, psychologist, Univ. of the Physics and professor of history of science, of medicine, Stanford Univ. West of England, Bristol Harvard Univ. -

MORGAN STREBLER Lite MAN of STEEL PLUS: REVIEWS MAGIC FRANKENSTEIN MAGIC BURNOUT

Issue No. 1 MORGAN STREBLER Lite MAN OF STEEL PLUS: REVIEWS MAGIC FRANKENSTEIN MAGIC BURNOUT HenryNEW Harrius KID ON THE BLOCK! THE OPENER A WORD FROM THE EDITORelcome to taster of what we included in the selection of some of the many opposed to the semi-skimmed, Magicseen regular full version. product reviews from the May we are happy to invite you to Lite! We’ll edition too. subscribe (details inside), as admit that we So, inside you will find our feature then you will not only receive are excited to article on cover star Henry Add to this interesting adverts every two months the full edition, be able to offer Harrius, a whizz if ever there was from some of the more important but also get it a month before Wyou the chance to experience with Rubik’s Cube magic, and we magic suppliers from around the Lite version hits the streets. some of what Magicseen is also get up close and personal the world, and we hope you’ll Subscribers also get 20% off all about with this special with Morgan Strebler, who has agree with us when we contend every book order they make with version of the May 2019 a very individual approach to his that this is an interesting mix. Magicseen too. But the choice issue. magic life. Our intention is to provide a Lite is yours. version a month after each future Magicseen Lite is a digital only Dominic Reyes provides a issue is released, so if you like Either way, welcome to the edition and can be downloaded thought provoking article on this one, look out for the next on Magicseen fold! completely free! Inside you will how to prevent yourself suffering the 1st August. -

By Joshua Jay Dr

In September 2014, I received an email from After the show, I shared my doubts with By Joshua Jay Dr. Lisa Grimm, who asked me to perform Dr. Grimm about some of the fundamental magic and speak in her college classroom. Dr. “truths” in magic that I had become skeptical Grimm is a researcher and Professor of Psy- about. How much do people care about the chology at The College of New Jersey, where secrets? What makes for strong magic? Are she also conducts research on human cognition. people really as fooled as we think they are? I As magicians, we deceive our She wanted an insider’s perspective from a had dozens of questions. While she didn’t know audiences. But are we deceiving magician. She believes — correctly, I think — the answers, she had a path to finding them: ourselves? Are there things — big that magicians have a lot to offer the field of statistics, experimentation, and analysis. things — that we get wrong about psychology, and vice versa. It sounded like a Our collaboration began in January 2015 our craft? And more importantly, are fun gig, so I booked it. and continues today. In partnership with Dr. there things our audiences can tell I opened with some magic, then spoke to Grimm and The College of New Jersey, we us that we aren’t asking? the group. I always use the same talking points have designed experiments to gather quan- The answers, it turns out, are for speaking engagements: the basics of misdi- titative and qualitative data on the topics of “yes” and “hell yes.” rection, and why magic is important. -

1976: Seckel Attends Cornell Summer and Fall Semesters As a “Special Student” (Provisional Admission, Not a Degree Candidate)

1976: Seckel attends Cornell summer and fall semesters as a “special student” (provisional admission, not a degree candidate). Summer: gets F in physics. Fall: takes Pearce Williams science history class (gets B), calculus (grade of “not attending”), and repeats physics (“no grade reported”). 1977: Seckel applies for Cornell spring semester admission but is rejected. 1978: Seckel attends fall semester as “special student.” Takes only German, gets D. End of Cornell attendance. 1980 June: Seckel marries Laura Mullen (Cornell ’80). 1980 or 1981: Seckel visits Bertrand Russell Archives (McMaster Univ., Ontario). 1980: Suzy Shaw, formerly married to Greg Shaw of Bomp Records, begins relationship with Brett Gurewitz of punk-rock band Bad Religion. She continues to help Greg run Bomp. 1981 June: Seckel elected Vice-Director of American Atheists’ Los Angeles chapter. http//www.miltontimmons.com/AUHistory.html 1981 Nov 9: In letter to Dick James, Madalyn Murray O’Hair accuses Seckel of plagiarism in article about Hypatia (she and Queen Silver had both previously written about Hypatia). 1981 Nov 22: Seckel and other officers of American Atheists L.A. chapter resign following dispute with national leader O’Hair. Atheists United formed soon after as independent group. 1981-1984: Seckel writes flyers for Atheists United, some co-authored with AU director John Edwards. 1982: Seckel gives speech for Atheists United at an Orange County high school. 1982: Seckel quoted by Debbie Cohen as saying he hosted 1982 Jerry Andrus lecture at Caltech (perhaps referring to 1985 SCS lecture?). http://www.goodreads.com/author/show/296832.Debbie_Cohen/blog 1982 or 1983: Atheists United flyer by John Edwards and Seckel with Darwin fish drawing (drawn by Edwards). -

Prices Correct Till May 19Th

Online Name $US category $Sing Greater Magic Volume 18 - Charlie Miller - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Greater Magic Volume 42 - Dick Ryan - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Greater Magic Volume 23 - Bobo - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Greater Magic Volume 20 - Impromptu Magic Vol.1 - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Torn And Restored Newspaper by Joel Bauer - DVD$ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 City Of Angels by Peter Eggink - Trick $ 25.00 Tricks$ 40.00 Silk Poke Vanisher by Goshman - Trick $ 4.50 Tricks$ 7.20 Float FX by Trickmaster - Trick $ 30.00 Tricks$ 48.00 Stealth Assassin Wallet (with DVD) by Peter Nardi and Marc Spelmann - Trick$ 180.00 Tricks$ 288.00 Moveo by James T. Cheung - Trick $ 30.00 Tricks$ 48.00 Coin Asrah by Sorcery Manufacturing - Trick $ 30.00 Tricks$ 48.00 All Access by Michael Lair - DVD $ 20.00 Videos$ 32.00 Missing Link by Paul Curry and Mamma Mia Magic - Trick$ 15.00 Tricks$ 24.00 Sensational Silk Magic And Simply Beautiful Silk Magic by Duane Laflin - DVD$ 25.00 Videos$ 40.00 Magician by Sam Schwartz and Mamma Mia Magic - Trick$ 12.00 Tricks$ 19.20 Mind Candy (Quietus Of Creativity Volume 2) by Dean Montalbano - Book$ 55.00 Books$ 88.00 Ketchup Side Down by David Allen - Trick $ 45.00 Tricks$ 72.00 Brain Drain by RSVP Magic - Trick $ 45.00 Tricks$ 72.00 Illustrated History Of Magic by Milbourne and Maurine Christopher - Book$ 25.00 Books$ 40.00 Best Of RSVPMagic by RSVP Magic - DVD $ 45.00 Videos$ 72.00 Paper Balls And Rings by Tony Clark - DVD $ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Break The Habit by Rodger Lovins - Trick $ 25.00 Tricks$ 40.00 Can-Tastic by Sam Lane - Trick $ 55.00 Tricks$ 88.00 Calling Card by Rodger Lovins - Trick $ 25.00 Tricks$ 40.00 More Elegant Card Magic by Rafael Benatar - DVD$ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Elegant Card Magic by Rafael Benatar - DVD $ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Elegant Cups And Balls by Rafael Benatar - DVD$ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Legless by Derek Rutt - Trick $ 150.00 Tricks$ 240.00 Spectrum by R. -

Avisit to Main Street Magic Page 36

OCTOBER 2015 Volume 105 Number 4 AVisit to Main Street Magic Page 36 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan 40.00 Proofreader & Copy Editor $3 Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Online Edition Coordinator Bruce Kalver Publisher Society of American Magicians, 4927 S. Oak Ct., Littleton, CO 80127 SPECIAL OFFER! Copyright © 2015 $340 or 6 monthly payments of $57 Subscription is through membership Shipped upon first payment! in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues EVERYTHING YOU NEED should be addressed to: TO SOUND LIKE A PRO You could open the box at your show! Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator 4927 S. Oak Ct. Littleton, CO 80127 [email protected] For audiences of up to 400 people. Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 All-inclusive! Handheld, Headsets, lapel Fax: 303-362-0424 mics, speaker, receiver (built in), highest quality battery, inputs, outputs.. www.mum-magazine.com SPEAKER STAND, HARD CASE, CORDS. To file an assembly report go to: For advertising information, All for just $340 reservations, and placement contact: Most trusted system on the market. Cinde Sanders, M-U-M Advertising Manager Email: [email protected] Telephone: 214-902-9200 Editorial contributions and correspondence Package Deal includes: concerning all content and advertising Amazing Amp speaker, removable re- should be addressed to the editor: chargeable 12V battery, power cord, (2) Michael Close - Email: [email protected] headset mics, (2) lapel mics, carrying Phone: 317-456-7234 Submissions for the magazine will only be bag, (3) 9V batteries, (2) belt pack accepted by email or fax. -

Close-Up Magic Materials/Michael J. Amico Papers Inventory

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Close-Up Magic/Amico Papers Inventory Close-Up Magic Materials/Michael J. Amico Papers Processed by: Cheri Crist (2007); inventory revised by Doris C. Sturzenberger Custodial History: The Library of The Strong acquired this group of papers related to the practice of close-up magic from Lars Sandel in July 1992. Sandel provided a comprehensive list of items included in the collection; however, there was no indication or record of the manner by which he came to acquire the items, nor is there any specific mention of the papers of Michael Amico. The original lot included books, booklets, and serials, which were added to the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play. The lot also included three-dimensional items, which were transferred to the Museum of Play collections. The papers had been divided into two boxes: one that contained personal papers of Michael J. Amico, a local, semi-professional, close-up magician; the other, a large number of magic trick instructions, along with a few items that seemed to relate directly or indirectly to Michael Amico. Some of the Amico-related items in the second box were from the Society of American Magicians (both the local and national groups), of which Amico was a member, while others had the word Amico written on them. One item mentions Bob Follmer, who was a friend of Amico. It is unknown how the two boxes are related. Because the same Object ID (93.7077) had been assigned to both sets of papers, the processor made the decision to integrate the two collections into one combined collection. -

Donothave.Pdf

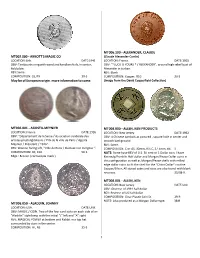

MT006.100 - ALEXANDER, CLAUDE MT002.000 - ABBOTT'S MAGIC CO (Claude Alexander Conlin) LOCATION: Unk. DATE:1946 LOCATION: France. DATE:1915 OBV: Tambourine ring with wand and handkerchiefs, in center, OBV: "*LUCK IS YOURS * / ALEXANDER", around high relief bust of field plain. Alexander in turban. REV: Same. REV: Blank. COMPOSITION: GS, R9. 39-S COMPOSITION: Copper, R10. 20-S May be of European origin. more information to come. (Image from the David Copperfield Collection) MT006.001 - AGOSTA-MEYNIER MT008.000 - ALLEN, KEN PRODUCTS LOCATION: France. DATE:1926 LOCATION: New Jersey. DATE:1962 OBV: "Département de la Seine / Association syndicale des OBV: 4 Chinese symbols as pictured , square hole in center and artistes prestidigitateurs / Prix de la ville de Paris / Agosta smooth background. Meynier / Président / 1926". REV: Same. REV: Woman facing left, "Ville de Paris / Fluctuat nec mergitur ". COMPOSITION: C or GS, 30mm, R3; C, 37.5mm, R4. S COMPOSITION: BZ, R10. 50-S NOTE: Some have REV of U.S. 50 cent or 1 Dollar coin. I have Edge : Bronze ( cornucopia mark ) Kennedy/Franklin Half dollar and Morgan/Peace Dollar coins in this configuration as well as Morgan/Peace shells with milled edge dollar coins to fit the shell for the “China Dollar” routine Copper/Silver, All stated coins and sizes are also found with blank reverses. 35/38-R. MT008.001 - ALLEN, KEN LOCATION: New Jersey. DATE:Unk OBV: Obverse of 1944 half dollar REV: Reverse of US half dollar COMPOSITION: Clear Plastic Coin St. 29-R NOTE: Also produced as a Morgan Dollar type. 38-R MT006.050 - ALADDIN, JOHNNY LOCATION: USA. -

On Leaping and Looking D Critical Thinking Boulder Critical Thinking Workshop

CSICOP News On Leaping and Looking d Critical Thinking Boulder Critical Thinking Workshop J. p. MCLAUGHLIN here couldn't have been a more University, who is an expert on Munc- ed to showing us the mental traps many appropriate locale for a meet- hausen syndrome; and Jerry Andrus, an fall into when trying to solve them. ing of skeptics last August in illusionist from Oregon who specializes (The simplest and most egregious T in "up-close magic" and sage observa- Boulder, Colorado—a theater of sci- example: How many animals of each ence where the only stars are the stars. tions on the human condition. Hyman kind did Moses take on the ark? Look About 80 of us gathered in Fiske and Beyerstein serve on CSICOP's twice before you leap.) Planetarium on the University of Executive Council. Our four leaders all touched on the Colorado campus for the CSICOP Those attending the workshop evolutionary aspects of thinking, how Workshop on Critical Thinking, a ranged from a Fermi Lab physicist to a brain evolution, in its pragmatic way, four-day conference that took apart the homemaker, a preschool teacher to causes us to leap before we look. For phenomenon of human thinking from several college professors, a substitute survival, it is indeed better to be safe the standpoints of evolution, psychol- teacher to a salesman ("We need pro- than sorry. ogy, and pathology. motion. Where are the TV cameras?), "Evolution leads us to jump to con- An even simpler theme of the work- computer specialists to psychologists, clusions—it is functional to survival shop may have been "Look Before You a former fundamentalist preacher but not necessarily the best way," Leap," a warning that echoed and re- racked by doubts, an antireligion pros- Beyerstein said. -

DOC SWAN Page 36

OCTOBER 2013 DOC SWAN Page 36 OCTOBER 2013 - M-U-M Magazine 3 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan Proofreader & Copy Editor Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Publisher Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr. Parker, CO 80134 Copyright © 2012 Subscription is through membership in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues should be addressed to: Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134 [email protected] Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 Fax: 303-362-0424 Send assembly reports to: [email protected] For advertising information, reservations, and placement contact: Cinde Sanders M-U-M Advertising Manager Email: [email protected] Telephone: 214-902-9200 Editorial contributions and correspondence concerning all content and advertising should be addressed to the editor: Michael Close - Email: [email protected] Phone: 317-456-7234 Submissions for the magazine will only be accepted by email or fax. VISIT THE S.A.M. WEB SITE www.magicsam.com To access “Members Only” pages: Enter your Name and Membership number exactly as it appears on your membership card. 4 M-U-M Magazine - OCTOBER 2013 M-U-M OCTOBER 2013 MAGAZINE Volume 103 • Number 5 COVER STORY PAGE 36 42 S.A.M. NEWS 6 From the Editor’s Desk 32 8 From the President’s Desk 10 Good Cheer List 11 M-U-M Assembly News 22 Broken Wands 69 S.A.M.