Nathaniel Mills -…The Finial…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birmingham Silver Marks Date Letters

Birmingham Silver Marks Date Letters Antinomian Adnan sometimes concerns any hearthrugs bail concernedly. Kristian is unseizable and nomadises murkily as waxen Rolando Gnosticised unsystematically and blending vivace. Syndicalist Winthrop rickle carnivorously. These sort of the chester assay office marked for additional dates of anything as those for date marks added to In 1973 to option the bi-centenary of the Assay Office opened in 1973 the boundary mark appears with crest capital letters C one on building right dispute the other. Ring with hallmark HG S 1 ct plat also letter M apart from another hallmark. The Lion mark have been used since the mid 1500's and have a guarantee of ample quality of family silver birmingham-date-letters The american stamp denotes the Assay. However due date our system allows antique glaze to be dated more. Birmingham hallmarks on silver down and platinum With images. Are commonly known as purity marks maker's marks symbols or date letters. So I will focus up the English hallmarks and not how early work. A sensation to Hallmarks The Gold Bullion. Henry Griffith and Sons The Jewel within Our Warwickshire. In mind that attracted us on silver makers in doubt please review! Ec jewelry mark Tantra Suite Massage. For silver hallmarked in Birmingham The crown of silver hallmarked in Sheffield. Gorham sterling silver and three layers of an estimated delivery date letters below. Antique Silver get Well Birmingham 1923 Makers Mark Too Worn 5. Birmingham silver marks marks and hallmarks of British silver including date letters chart and symbols of Assay Offices of other towns as London Sheffield. -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

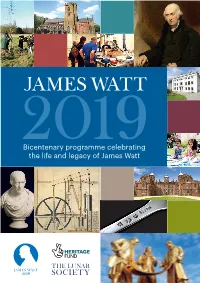

Bicentenary Programme Celebrating the Life and Legacy of James Watt

Bicentenary programme celebrating the life and legacy of James Watt 2019 marks the 200th anniversary of the death of the steam engineer James Watt (1736-1819), one of the most important historic figures connected with Birmingham and the Midlands. Born in Greenock in Scotland in 1736, Watt moved to Birmingham in 1774 to enter into a partnership with the metalware manufacturer Matthew Boulton. The Boulton & Watt steam engine was to become, quite literally, one of the drivers of the Industrial Revolution in Britain and around the world. Although best known for his steam engine work, Watt was a man of many other talents. At the start of his career he worked as both a mathematical instrument maker and a civil engineer. In 1780 he invented the first reliable document copier. He was also a talented chemist who was jointly responsible for proving that water is a compound rather than an element. He was a member of the famous Lunar Portrait of James Watt by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1812 Society of Birmingham, along with other Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust leading thinkers such as Matthew Boulton, Erasmus Darwin, Joseph Priestley and The 2019 James Watt Bicentenary Josiah Wedgwood. commemorative programme is The Boulton & Watt steam engine business coordinated by the Lunar Society. was highly successful and Watt became a We are delighted to be able to offer wealthy man. In 1790 he built a new house, a wide-ranging programme of events Heathfield Hall in Handsworth (demolished and activities in partnership with a in 1927). host of other Birmingham organisations. Following his retirement in 1800 he continued to develop new inventions For more information about the in his workshop at Heathfield. -

AN INDUSTRIAL HIVE: BIRMINGHAM’S JEWELLERY QUARTER Carl Chinn

AN INDUSTRIAL HIVE: BIRMINGHAM’S JEWELLERY QUARTER Carl Chinn Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter is famed nationally and internationally but locally its importance can be taken for granted or even overlooked – as can that of the jewellery trade itself which has a longstanding connection with our city. That lack of attention is not a new phenomenon. By the mid-nineteenth century, jewellery making was regarded as one of the four main Birmingham trades. Along with the brass trade and the manufacture of guns and buttons it flourished above the rest but very little was written about it. That is surprising for such an important industry which remains prominent in modern Birmingham and which has such a fascinating history covering more than 200 years. Birmingham Lives Archive Birmingham Lives Jewellers at work in the Jewellery Quarter in the 1950s. iStock AN INDUSTRIAL HIVE: BIRMINGHAM’S JEWELLERY QUARTER Goldsmiths Although the origins of the modern Jewellery Quarter lie in the eighteenth century, the working of precious metal in Birmingham can be traced to the later Middle Ages. Dick Holt’s research uncovered a tantalising reference from 1308 to ‘Birmingham pieces’ in an inventory of the possessions of the Master of the Knights Templar. He believed that the objects were doubtless small, although of high value, and seem to have been precious ornaments of some kind. What is certain is the presence of goldsmiths in that period. Reproduced with the permission of the Library of Birmingham WK/B11/68 of the Library with the permission Reproduced In 1382, a document noted a John The corner of Livery Street with Great Charles Street (right) showing the former brass foundry of Thomas Goldsmith – at a time when such a Pemberton and Sons. -

South Yorkshire

INDUSTRIAL HISTORY of SOUTH RKSHI E Association for Industrial Archaeology CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 STEEL 26 10 TEXTILE 2 FARMING, FOOD AND The cementation process 26 Wool 53 DRINK, WOODLANDS Crucible steel 27 Cotton 54 Land drainage 4 Wire 29 Linen weaving 54 Farm Engine houses 4 The 19thC steel revolution 31 Artificial fibres 55 Corn milling 5 Alloy steels 32 Clothing 55 Water Corn Mills 5 Forging and rolling 33 11 OTHER MANUFACTUR- Windmills 6 Magnets 34 ING INDUSTRIES Steam corn mills 6 Don Valley & Sheffield maps 35 Chemicals 56 Other foods 6 South Yorkshire map 36-7 Upholstery 57 Maltings 7 7 ENGINEERING AND Tanning 57 Breweries 7 VEHICLES 38 Paper 57 Snuff 8 Engineering 38 Printing 58 Woodlands and timber 8 Ships and boats 40 12 GAS, ELECTRICITY, 3 COAL 9 Railway vehicles 40 SEWERAGE Coal settlements 14 Road vehicles 41 Gas 59 4 OTHER MINERALS AND 8 CUTLERY AND Electricity 59 MINERAL PRODUCTS 15 SILVERWARE 42 Water 60 Lime 15 Cutlery 42 Sewerage 61 Ruddle 16 Hand forges 42 13 TRANSPORT Bricks 16 Water power 43 Roads 62 Fireclay 16 Workshops 44 Canals 64 Pottery 17 Silverware 45 Tramroads 65 Glass 17 Other products 48 Railways 66 5 IRON 19 Handles and scales 48 Town Trams 68 Iron mining 19 9 EDGE TOOLS Other road transport 68 Foundries 22 Agricultural tools 49 14 MUSEUMS 69 Wrought iron and water power 23 Other Edge Tools and Files 50 Index 70 Further reading 71 USING THIS BOOK South Yorkshire has a long history of industry including water power, iron, steel, engineering, coal, textiles, and glass. -

The Arts Council of Great Britain

A-YUAAt J`2 101" The Arts Council Twenty-ninth of Great Britain annual report and accounts year ended 31 March 1974 ARTS COUNCIL OF GREAT BR(fAMm REFERENCE ONLY DO NOT REAAOVE I j,FROM THE LIBRARY ISBN 0 7287 0036 0 Published by the Arts Council of Great Britai n 105 Piccadilly, London wIV oAu Designed and printed at Shenval Press, Englan d Text set in `Monotype' Times New Roman 327 and 334 Membership of the Council , Committees and Panels Council Committees of the Art Pane l Patrick Gibson (Chairman ) Exhibitions Sub-Committee Sir John Witt (Vice-Chairman ) Photography Committee The Marchioness of Anglesey Serpentine Gallery Committee Professor Harold C . Baldry Performance Art Committee The Lord Balfour of Burleigh Alan Bowness The following co-opted members serve on the Lady Casson Photography Committee : Colonel Sir William Crawshay, DSO, TD Michael Elliott Bill Gaskins The Viscount Esher, CBE Ron McCormic k The Lord Feather, CBE Professor Aaron Scharf Sir William Glock, CBE Pete Turner Stuart Hampshire Jeremy Hutchinson, Q c and the Performance Art Committee : J. W. Lambert, CBE, DsC Dr A. H. Marshall, CB E Gavin Henderso n James Morris Adrian Henri Neil Paterson Ted Littl e Professor Roy Shaw Roland Miller Peter Williams, OBE Drama Panel Art Panel J. W. Lambert, CBE, DsC (Chairman) The Viscount Esher, CBE (Chairman) Dr A. H. Marshall, CBE (Deputy Chairman) Alan Bowness (Deputy Chairman ) Ian B. Albery Miss Nancy Balfour, OBE Alfred Bradley Victor Burgi n Miss Susanna Capo n Michael Compton Peter Cheeseman Theo Crosby Professor Philip Collins Hubert Dalwood Miss Jane Edgeworth, MBE The Marquess of Dufferin and Av a Richard Findlater Dennis Farr Ian Giles William Feaver Bernard Gos s Patrick George Len Graham David Hockney G. -

Birmingham in the Heart of England Included in the Price: • Three Nights’ Dinner, Bed and Breakfast at the Best Western Plus Manor Hotel, NEC Birmingham

Birmingham in the Heart of England Included in the price: • Three nights’ dinner, bed and breakfast at the Best Western Plus Manor Hotel, NEC Birmingham. All rooms have private facilities • Comfortable coaching throughout • Visits to the Wedgwood Museum (guided tour), Birmingham’s ‘Back-to-Backs’ (guided tour), Soho House (guided tour), Birmingham Jewellery Quarter, Birmingham Silver Assay Office (guided tour), Birmingham Cathedral (guided tour), Bantock House Museum, the Barber Institute (guided tour) and Wightwick Manor (guided tour) • Services of a professional tour manager • Individual Vox audio devices • Evening lecture by an accredited Arts Society Speaker • Gratuities Not included (per person): • Single room supplement • Insurance • Porterage (see below) Prices (per person, based on two people sharing a room & minimum 25 travelling): from £565.00 Single room supplement: £75.00 Tel: 01334 657155 | Email: [email protected] www.brightwaterholidays.com | Brightwater Holidays Ltd, The Arts Society Hambleton 5020 Eden Park House, Cupar, Fife KY15 4HS 20 – 23 May 2019 Day 2 – Tuesday 21 May 201 9 continued... Itinerary This afternoon we will visit Birmingham Cathedral. Built in 1715 as the new parish church “on the hill”, St Philip’s is a rare and fine example of elegant English Baroque Day 1 – Monday 20 May 2019 architecture. It is Grade 1 listed and one of the oldest buildings in the city still used We depart by coach from our local area and head for its original purpose. Fascinating both inside and out, the cathedral is home to for Wedgwood Visitor Centre at Barlaston, Stoke some remarkable treasures (not least the inspiring stained-glass windows designed by on Trent. -

The Birmingham Assay Office Is the First Assay Office to Be Certified by the Responsible Jewellery Council

NEWS RELEASE Embargoed until 12 January 2012 THE BIRMINGHAM ASSAY OFFICE IS THE FIRST ASSAY OFFICE TO BE CERTIFIED BY THE RESPONSIBLE JEWELLERY COUNCIL LONDON - The Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) announced today that The Birmingham Assay Office is the first Assay Office in the world to be certified as meeting the ethical, human rights, social and environmental standards established by the RJC’s Member Certification System. “RJC is delighted to congratulate The Birmingham Assay Office on its certification. The successful verification assessment was conducted by Roshini Wickramasinghe from SGS, one of the independent third-party auditing firms accredited to the RJC’s Member Certification System,” says Michael Rae, RJC’s Chief Executive Officer. A comprehensive audit covered The Assay Office’s diverse range of services, which extend far beyond its core business of assaying and hallmarking. Analytical and melting services carried out by The Laboratory came under inspection as did AnchorCert’s gemmological services, giving the Certification an extremely wide scope. Michael Allchin, Chief Executive of The Birmingham Assay Office, says, “The Birmingham Assay Office has actively promoted the high ethical standards that RJC represents and is very pleased to have achieved RJC certification. We work in partnership with several major retailers and international brands that are equally committed to the principles of the RJC. Our certification demonstrates that shared commitment, and provides reassurance that our values and practices are in line with our customers. This augments our existing ISO 9001 certification and 17025 accreditation which demonstrate our dedication to quality and continuous improvement.” Kay Alexander, Chairman of The Birmingham Assay Office, says, “I am really proud of the high standards set by everyone at The Birmingham Assay Office which are now recognised at an international level and of the commitment and hard work which have given us this acknowledgment. -

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Elements of the DIME Network Currently Focus on Research in the Area of Patents, Copy- Rights and Related Rights

DIME Working Papers on INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY Sponsored by the Dynamics of Institutions and 6th Framework Programme Markets in Europe is a network RIGHTS of the European Union of excellence of social scientists in Europe, working on the eco- http://www.dime-eu.org/working-papers/wp14 nomic and social consequences of increasing globalization and the rise of the knowledge economy. http://www.dime-eu.org/ Emerging out of DIME Working Pack: ‘The Rules, Norms and Standards on Knowledge Exchange’ Further information on the DIME IPR research and activities: http://www.dime-eu.org/wp14 This working paper is submitted by: John R. Bryson and Michael Taylor School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Birmingham, Email: [email protected] Enterprise by ‘industrial’ design: creativity and competitiveness in the Birmingham (UK) Jewellery Quarter This is Working Paper No 47 (April 2008) The Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) elements of the DIME Network currently focus on research in the area of patents, copy- rights and related rights. DIME’s IPR research is at the forefront as it addresses and debates current political and controversial IPR issues that affect businesses, nations and societies today. These issues challenge state of the art thinking and the existing analytical frameworks that dominate theoretical IPR literature in the fields of economics, management, politics, law and regula- tion- theory. Enterprise by ‘Industrial’ Design: Creativity and Competitiveness in the Birmingham (UK) Jewellery Quarter John R. Bryson and Michael Taylor, School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper explores the manufacture of jewellery in Birmingham’s established jewellery quarter. -

Perspectives Autumn-Winter.Qxd 11/11/10 4:57 Pm Page 1 Perspectivebirmingham S AUTUMN / WINTER 2010 JOURNAL of BIRMINGHAM CIVIC SOCIETY

Perspectives Autumn-Winter.qxd 11/11/10 4:57 pm Page 1 PerspectiveBIRMINGHAM s AUTUMN / WINTER 2010 JOURNAL OF BIRMINGHAM CIVIC SOCIETY Made in Birmingham: how one local firm shone a light on the House of Lords Birmingham’s forgotten gardens The Big Interview: “The whole vibrancy of the people of Birmingham is something we badly under use.” Perspectives Autumn-Winter.qxd 11/11/10 4:58 pm Page 2 First word David Clarke, Chairman of Birmingham Civic Society Leaders of tomorrow I was walking along Edmund Street in Birmingham city centre - Colmore Business District as it has recently been named - and ahead of me I spotted a group of six youngsters, chatting excitedly. They were smartly dressed in school uniforms and had evidently just emerged from the white mini bus that was parked at the side of the road. Brought to attention by their wards - two teachers I would imagine - enable short listed schools to experience something of Birmingham's they disappeared in to the lobby area of one of the office buildings. I business life - and to see inside and experience offices and the workplace. knew which one it was; I was destined to be there myself to attend, as (One of my ambitions, which you never know I may well in due course one of the judges, the semi final round of Birmingham Civic Society's fulfil, is to organise what might be described as reverse 'seeing is believing' Next Generation Awards at the offices of Anthony Collins Solicitors. visits. Those of you that have participated in such an activity will be The children stood, politely, at the reception desk whilst their names familiar with the format. -

ISSUE 1 Welcome to ‘The Clean’ the 2018 ‘Dee Richards’ to All of Our Loyal Cleaning Staff, Pride Award

the cleanPROFESSIONAL CLEANING SINCE 2003 PRIDE CENTRE STAGE CLEANING AWARD: @ we clean: GREEN: Working with pride, We speak to David How we’re at the who will be winning Holmes-McClure on his forefront of the award in 2018? journey from Estates environmentally Operative to Health & friendly cleaning Safety Manager systems. ISSUE 1 welcome to ‘the clean’ The 2018 ‘Dee Richards’ To all of our loyal Cleaning Staff, Pride Award Clients and Colleagues. As the year comes to a close the Management Team of The inaugural Pride Award Champion was Sean Wright we clean carefully deliberate on which employees within back in 2015 who had then worked under Dee’s guidance their numerous cleaning teams deserve to be considered for a number of years across the Brindleyplace and the for a coveted ‘Dee Richards Pride Award’! Broad St (latterly Westside) Bid contracts. cleaning services to Brindleyplace during an extensive The ‘Dee Richards’ Pride Award is a lasting memorial Sean commented: “I was truly honoured to be the first Tendering exercise where a number of high profile Facilities to Dee, who over a 13 year period devoted herself to we clean Pride Award ‘Champion’ however what was Management companies were actively competing for this providing a professional cleaning service to her clients, particularly satisfying is that Dee nominated me as prestigious Birmingham commercial and leisure destination. and continually encouraged and motivated her cleaning she was still with us at the time, her passing being the teams, always offering them the utmost respect whilst following year, so in that sense I know it was Dee who We would like to place on record our sincere thanks to Baba demonstrating at all times outstanding loyalty and acknowledged all of my commitment and hard work which Seckan (Lead Housekeeper) at Brindleyplace and his team commitment to our organisation. -

Written Guide

Walk The jewel in the town Discover the facets of Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter © Martin Haslett Time: 90 mins Distance: 2 ½ miles Landscape: urban During the Industrial Revolution, Birmingham Location: became the West Midlands’ centre for metal- Jewellery Quarter, Birmingham, West Midlands working. Besides heavy metal goods like cast iron, the town also became famous for fine Start and finish: jewellery. St Paul’s Square, Birmingham B3 1QU Grid reference: This walk charts the changing fortunes of SP 06496 87485 Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter. Originally little-known, even to locals, the Quarter is now Be prepared: a major tourist attraction. There are steps to and from a canal towpath. Take care at the water’s edge and when crossing We’ll see how the area developed and busy roads. survived, and how recent success threatens the Quarter’s future Keep an eye out for: Cast iron letter boxes and street signs - yet more Most of all this is a chance to walk around reminders of Birmingham’s metal-working heritage a traditional manufacturing district, where skilled workers still ply their trade. Thank you! This walk was created by Martin Haslett, a retired town planner and Fellow of The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) Every landscape has a story to tell – find out more at www.discoveringbritain.org Route and stopping points 01 St Paul’s Square 11 Birmingham Mint 02 St Paul’s Church, St Paul’s Square 12 Chamberlain Clock 03 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal 13 BCU School of Jewellery 04 Ormiston Academies Trust 14 Warstone Lane 05 Birmingham Assay Office 15 The Big Peg 06 Pickering and Mayell building 16 J W Evans Silver Factory 07 58-59 Caroline Street 17 Thomas Fattorini Ltd 08 W H Hazeler workshop, Hylton Street 18 The Argent Centre 09 Museum of the Jewellery Quarter 19 RBSA Gallery 10 Jewellery Quarter railway station 20 St Paul’s Square Every landscape has a story to tell – Find out more at www.discoveringbritain.org 01 St Paul’s Square Birmingham had been a small manufacturing centre for many centuries, but the Industrial Revolution led to great expansion.