Edu Immigration ACCEPTED.Pdf (882.2Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faktaark for Kulturminnelokalitet 1050193 Elvebråten Sikkeland Østre

Lok. nr. 1050193 Elvebråten Sarpsborg http://kulturminnekart.no/ostfold/?x=284284&y=6579778 Gårdsnavn: Sikkeland østre Gnr/bnr: 3042/8 Koordinat: Ø: 625888, N: 6575730, 22 EU89-UTM Sone 32 Synbarhet: Kulturminneregistrering KMtype: Husmannsplass, , Tilstand: Tapt Verneverdi: Vern: Ikke fredet lokalt kulturminne, Beskrivelse: Opprinnelig en husmannsplas ryddet på 1700-tallet. Navnet var først Arvebraaten, men ble etter hvert til Elvebraaten. Det er bygd et nytt hus på plassen. Plassen ble utskilt fra gnr 3042 Sikkeland østre på 1800-tallet. Gården fikk da bnr 8. Cornelius Olsen (1764-5. september 1834) fra Bergsland nevnes her i 1801 og utetter. Ved folketellingen 1801 ble Cornelius beskrevet som husmann med jord på Arvebraaten plads. Han var gift med Marthe Olsdatter (født 1768 på Bergby, død 1811). Deres barn var Ole (1794-1882), Lars (f. 1796), Oleane (f. 1798) og Mathis (f. 1800, død 9. juni 1873 som gift fattiglem på Bergsland). Enken Maria Svendsdatter var inderste. Ole kom til Engebråten, Lars kom til Bergbyhaugen og Mathis kom til Bergslandhaugen. Cornelius ble enkemann i 1811 og giftet seg samme år med Anne Andersdatter Kokkim (1782-1843). Cornelius døde formodentlig av kolera den 5. september 1834, og han ble begravet på Varteig kolerakirkegård. Andreas Arvesen (f. 1803 på Ise), sønn av Arve Børresen og Rønnaug Olsdatter Velta kjøpte Elvebraaten. Andreas giftet seg med Ellen Olsdatter fra Karlsbraaten (f. 1811). I 1865 sto de som eiere og bodde da selv på gården med eldstesønnen Anders (f. 16. juli 1836) og svigerdatteren Inger Marie Kristiansdatter (f. 1829 i Eidsberg). Ti år senere bodde Andreas og Ellen alene på Elvebraaten. -

Ny Lufthavn I Mo I Rana

Ekstern kvalitetssikring Prosjektnummer E033b Ny lufthavn i Mo i Rana Rapport til Samferdselsdepartementet og Finansdepartementet 15.03.2021 KS2 Ny lufthavn Mo i Rana – hovedrapport Superside Generelle opplysninger Kvalitetssikringen Kvalitetssikrer: Concreto AS Dato: 15.03.2021 Prosjektinformasjon Prosjektnavn og ev. nr.: Ny Departement: Prosjekttype: lufthavn i Mo i Rana Samferdselsdepartementet Lufthavnprosjekt, Avinor Basis for analysen Prosjektfase: Forprosjekt. Prisnivå: 2020 Tidsplan St.prp.: Prosjektoppstart: Planlagt ferdig: Andre halvår 2021 (samspill) Andre halvår 2026 Tema/sak Tiltakets samfunnsmål • Avinor skal ved utvikling og etablering av Prioritering 1. sikkerhet en ny lufthavn Mo i Rana legge til rette for av 2. ytre miljø et utvidet reisetilbud i tråd med resultatmål 3. kostnad markedsmessige behov og bidra til å styrke 4. kvalitet regionens mulighet for videre vekst. 5. tid • Lufthavnen skal dekke de markedsmessige behov (i tråd med trafikktall fra Urbanets ringvirkningsanalyse til SD, mottatt 29.mai 2015) for flyruter, charter og frakt på en måte som bidrar til verdiskapning, næringsutvikling og bosetting. Endringslogg Viktigste føringer for forprosjektet: Fastsatt styringsmål: Merknader: Prosjektet har ikke gjennomført KVU (eller KS1). Styringsmål (P50): Justeringer 2 320 mill. 2020- gjennomført kroner av EKS. Kostnadsramme (P85): 2 772 mill. 2020-kroner Kontraktstrategi Prosjektets anbefaling Prosjektet tilrår alternativ 1B, der arbeidet er organisert som én stor kontrakt med samspill på målpris, åpen bok og med insentivordninger i form av bonus/malus. Kvalitetssikrers anbefaling Avinor har ikke ferdigstilt vurderingen av kontraktstrategi. Vi tilrår forhold som bør inngå i denne vurderingen, bla. å ta ut U1 som en egen entreprise og vurdering av hvor langt samspillet skal tas før det lyses ut som totalentreprise og med muligheter for pris- og mengdereguleringer av særlig usikre deler av kalkylen. -

Forskrift Om Skolerute for Viken Skoleåret 2021-2022

Forskrift om skolerute for Viken skoleåret 2021-2022 Forskrift gitt med hjemmel i opplæringslovens §3-2. Vedtatt av fylkestinget i Viken fylkeskommune dato 21.oktober 2020 Skoleruta for skoleåret 2021-2022 for skoler i Hurdal, Eidsvoll, Nes, Aurskog-Høland, Marker, Aremark, Halden, Hvaler, Sarpsborg, Rakkestad, Fredrikstad, Råde, Moss, Våler, Skiptvedt, Indre Østfold, Vestby, Ås, Frogn, Nesodden, Nordre Follo, Enebakk, Lørenskog, Rælingen, Lillestrøm, Nittedal, Gjerdrum, Ullensaker, Nannestad, Asker og Bærum Skoledager elever Ferier, fridager, kommentarer August 10 Første skoledag: uke 33, onsdag 18.08 September 22 Oktober 16 Høstferie: uke 40: f.o.m. mandag 04.10 t.o.m. fredag 08.10 November 21 Onsdag 17.11 Fri for elever, felles plandag for lærere Desember 15 Juleferie f.o.m. onsdag 22.12 Januar 21 Juleferie t.o.m. søndag 02.01 Februar 15 Vinterferie uke 8: f.o.m. mandag 21.02 t.o.m. fredag 25.02 Mars 23 April 15 Påskeferie f.o.m lørdag 09.04 t.o.m. mandag 18.04 Mai 20 Fri/helgedag: 17.05, 26.05 Juni 12 Fri 06.06 Siste skoledag: fredag 17.06 Sum 190 Offentlige fridager: Søndag 01.05 Tirsdag 17.05 Torsdag 26.05 Kr. Himmelfartsdag Mandag 06.06 2. pinsedag Oslo, 25.06.2020 Skoleruta for skoleåret 2021-2022 for skoler i Hemsedal, Gol, Ål, Nes i Hallingdal, Hol, Nore og Uvdal, Modum, Flå, Ringerike, Hole, Krødsherad, Sigdal, Rollag, Flesberg, Øvre Eiker, Kongsberg, Drammen, Lier, Jevnaker og Lunner Skoledager elever Ferier, fridager, kommentarer August 10 Første skoledag: uke 33, onsdag 18.08 September 22 Oktober 16 Høstferie: uke 40: f.o.m. -

Anthropological Abstracts

Anthropological Abstracts Cultural/Social Anthropology from German-speaking countries edited by Ulrich Oberdiek Volume 3.2004 ___________ LIT Contents Editorial 4 General/Theoretical/Historical Studies 9 Regional Studies Africa 133 The Americas 191 Asia 219 Australia & Oceania 261 Europe 267 Periodicals scanned 327 Author Index 295 Subject Index Editorial This reference journal is published once a year and announces most publications in the field of cultural/social anthropology from the German language area (Austria, Germany, Switzerland). Since many of these publications have been written in German, and most German publications are not included in major, English language abstracting services, Anthropological Abstracts (AA) offers an opportunity and convenient source of information for anthropologists who do not read German to become aware of anthropological publications in German- speaking countries. Included are journal articles, monographs, anthologies, exhibition catalogs, yearbooks, etc., published in German. Occasionally, publications in English, or French, are included as well if the publisher is less well-known and when it is likely that the publication will not be noted abroad. The present printed volume of Anthropological Abstracts (AA) (2.2003) includes no. www-4 of the internet version (www.anthropology-online.de ’ Anthropological Abstracts ’ no. 4.2003); the printed version has about 30% additional material, however. Starting from the present volume the layout (size of script etc.) has been changed to ensure better readability. Some technical remarks This reference journal uses a combined and flexible approach of representation: While in most cases abstracts are supplied, for some anthologies and journals (e.g., Zeitschrift für Kulturaustausch, Kea) - because of space limitations - the Current Contents principle is applied, i.e. -

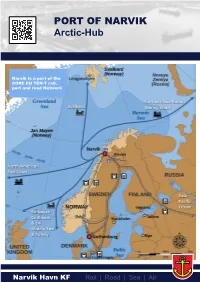

PORT of NARVIK Arctic-Hub

PORT OF NARVIK Arctic-Hub Narvik is a part of the CORE EU TEN-T rail, port and road Network 1 Arctic-Hub The geographic location of Narvik as a hub/transit port is strategically excellent in order to move goods to and from the region (north/south and east/west) as well as within the region itself. The port of Narvik is incorporated in EU’s TEN-T CORE NETWORK. On-dock rail connects with the international railway network through Sweden for transport south and to the European continent, as well as through Finland for markets in Russia and China. Narvik is the largest port in the Barents Region and an important maritime town in terms of tonnage. Important for the region Sea/port Narvik’s location, in relation to the railway, road, sea and airport, Ice-free, deep sea port which connects all other modes of makes the Port of Narvik a natural logistics intersection. transport and the main fairway for shipping. Rail Airport: The port of Narvik operates as a hub for goods transported by Harstad/Narvik Airport, Evenes is the largest airport in North- rail (Ofotbanen) to this region. There are 19 cargo trains, in ern Norway and is one of only two wide body airports north each direction (north/south), moving weekly between Oslo and of Trondheim. Current driving time 1 hour, however when the Narvik. Transportation time 27 hours with the possibility of Hålogaland Bridge opens in 2017, driving time will be reduced making connections to Stavanger and Bergen. to 40 minutes. The heavy haul railway between Kiruna and Narvik transports There are several daily direct flights from Evenes to Oslo, 20 mt of iron ore per year (2015). -

Folketeljing 1900 for 0215 Frogn Digitalarkivet

Folketeljing 1900 for 0215 Frogn Digitalarkivet 25.09.2014 Utskrift frå Digitalarkivet, Arkivverket si teneste for publisering av kjelder på internett: http://digitalarkivet.no Digitalarkivet - Arkivverket Innhald Løpande liste .................................. 9 Førenamnsregister ........................ 79 Etternamnsregister ...................... 101 Fødestadregister .......................... 123 Bustadregister ............................. 143 4 Folketeljingar i Noreg Det er halde folketeljingar i Noreg i 1769, 1801, 1815, 1825, 1835, 1845, 1855, 1865, 1870 (i nokre byar), 1875, 1885 (i byane), 1891, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1946, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990 og 2001. Av teljingane før 1865 er berre ho frå 1801 nominativ, dvs. ho listar enkeltpersonar ved namn. Teljingane i 1769 og 1815-55 er numeriske, men med namnelistar i grunnlagsmateriale for nokre prestegjeld. Statistikklova i 1907 la sterke restriksjonar på bruken av nyare teljingar. Etter lov om offisiell statistikk og Statistisk Sentralbyrå (statistikklova) frå 1989 skal desse teljingane ikkje frigjevast før etter 100 år. 1910-teljinga blei difor frigjeven 1. desember 2010. Folketeljingane er avleverte til Arkivverket. Riksarkivet har originalane frå teljingane i 1769, 1801, 1815-1865, 1870, 1891, 1910, 1930, 1950, 1970 og 1980, mens statsarkiva har originalane til teljingane i 1875, 1885, 1900, 1920, 1946 og 1960 for sine distrikt. Folketeljinga 3. desember 1900 Ved kgl. res. 8. august 1900 blei det bestemt å halde ei "almindelig Folketælling" som skulle gje ei detaljert oversikt over befolkninga i Noreg natta mellom 2. og 3. desember 1900. På kvar bustad skulle alle personar til stades førast i teljingslista, med særskild markering ("mt") av dei som var mellombels til stades (på besøk osb.) på teljingstidspunktet. I tillegg skulle alle faste bebuarar som var fråverande (på reise, til sjøs osb.) frå bustaden på teljingstidspunktet, også førast i lista, men merkast som fråverande ("f"). -

Angående FOT Ruter Fra 2022 Høringsuttalelse Fra Flyplassutvalget Ved Harstad/Narvik Lufthavn Evenes

Angående FOT ruter fra 2022 Høringsuttalelse fra Flyplassutvalget ved Harstad/Narvik lufthavn Evenes Bakgrunn Fylkeskommunene overtar ansvaret for FOT-flyrutene i fylkene fra Samferdselsdepartementet 1. april 2022, ved igangsetting av ny kontrakt. Denne kontrakten planlegges for perioden 2022 – 2027. I forkant av kontraktsoppstart skal fylkeskommunen gjennomføre anskaffelse, og det er planlagt igangsetting av anbudsprosess sent 2020 eller tidlig 2021. Evenes har fra nyttår fått på plass en viktig FOT forbindelse ti og fra Bodø med 2 avganger daglig. Denne knyttes til eksisterende rute Evenes – Tromsø. Begge kontraktene betjenes av Widerøes Flyveselskap. For regionen er begge disse forbindelsene viktig både ift fylkeshovedstedenes offentlige tjenester og for private reisende. Flyplassutvalget mener: De store endringene i reisevaner som koronapandemien har ført til har også endret betingelsene for finansieringen av FOT-rutene. Billettinntektene utgjør en vesentlig del av finansieringen i dag. Under pandemien har i gjennomsnitt 40 % av billettinntektene forsvunnet. Hvis passasjertallene i 2022 bedrer seg, men likevel ligger 20% under normalen før korona utgjør det et tap i Nordland alene på 100 MNOK. I denne situasjonen vil operatøren kunne ha behov for 100 millioner ekstra for å opprettholde eksisterende rutetilbud. Dette er ikke utgifter fylkeskommunene kan pålegges. Flyplassutvalget er derfor av den klare oppfatning at det må være tilstrekkelig finansiering til stede fra staten for å opprettholde dagens tilbud og frekvens Evenes-Bodø og Evenes-Tromsø også fra april 2022. Vi vil understreke at 2 avganger pr dag i hver retning uansett er et absolutt minimum for å ivareta viktige samfunnsfunksjoner og nødvendig samhandling innad i fylkene og regionene Flyplassutvalget vil fortsette å jobbe i forhold til sentrale myndigheter, samt fylkene for å kunne beholde et minimumstilbud i en luftfart preget av korona tiltak og effekter. -

Supplementary File for the Paper COVID-19 Among Bartenders And

Supplementary file for the paper COVID-19 among bartenders and waiters before and after pub lockdown By Methi et al., 2021 Supplementary Table A: Overview of local restrictions p. 2-3 Supplementary Figure A: Estimated rates of confirmed COVID-19 for bartenders p. 4 Supplementary Figure B: Estimated rates of confirmed COVID-19 for waiters p. 4 1 Supplementary Table A: Overview of local restrictions by municipality, type of restriction (1 = no local restrictions; 2 = partial ban; 3 = full ban) and week of implementation. Municipalities with no ban (1) was randomly assigned a hypothetical week of implementation (in parentheses) to allow us to use them as a comparison group. Municipality Restriction type Week Aremark 1 (46) Asker 3 46 Aurskog-Høland 2 46 Bergen 2 45 Bærum 3 46 Drammen 3 46 Eidsvoll 1 (46) Enebakk 3 46 Flesberg 1 (46) Flå 1 (49) Fredrikstad 2 49 Frogn 2 46 Gjerdrum 1 (46) Gol 1 (46) Halden 1 (46) Hemsedal 1 (52) Hol 2 52 Hole 1 (46) Hurdal 1 (46) Hvaler 2 49 Indre Østfold 1 (46) Jevnaker1 2 46 Kongsberg 3 52 Kristiansand 1 (46) Krødsherad 1 (46) Lier 2 46 Lillestrøm 3 46 Lunner 2 46 Lørenskog 3 46 Marker 1 (45) Modum 2 46 Moss 3 49 Nannestad 1 (49) Nes 1 (46) Nesbyen 1 (49) Nesodden 1 (52) Nittedal 2 46 Nordre Follo2 3 46 Nore og Uvdal 1 (49) 2 Oslo 3 46 Rakkestad 1 (46) Ringerike 3 52 Rollag 1 (52) Rælingen 3 46 Råde 1 (46) Sarpsborg 2 49 Sigdal3 2 46 Skiptvet 1 (51) Stavanger 1 (46) Trondheim 2 52 Ullensaker 1 (52) Vestby 1 (46) Våler 1 (46) Øvre Eiker 2 51 Ål 1 (46) Ås 2 46 Note: The random assignment was conducted so that the share of municipalities with ban ( 2 and 3) within each implementation weeks was similar to the share of municipalities without ban (1) within the same (actual) implementation weeks. -

AIBN Accident Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner, Oslo Airport, 18

Issued June 2020 REPORT SL 2020/14 REPORT ON THE AIR ACCIDENT AT OSLO AIRPORT GARDERMOEN, NORWAY ON 18 DECEMBER 2018 WITH BOEING 787-9 DREAMLINER, ET-AUP OPERATED BY ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES The Accident Investigation Board has compiled this report for the sole purpose of improving flight safety. The object of any investigation is to identify faults or discrepancies which may endanger flight safety, whether or not these are causal factors in the accident, and to make safety recommendations. It is not the Board's task to apportion blame or liability. Use of this report for any other purpose than for flight safety shall be avoided. Accident Investigation Board Norway • P.O. Box 213, N-2001 Lillestrøm, Norway • Phone: + 47 63 89 63 00 • Fax: + 47 63 89 63 01 www.aibn.no • [email protected] This report has been translated into English and published by the AIBN to facilitate access by international readers. As accurate as the translation might be, the original Norwegian text takes precedence as the report of reference. Photos: AIBN and Trond Isaksen/OSL The Accident Investigation Board Norway Page 2 INDEX ACCIDENT NOTIFICATION ............................................................................................................ 3 SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1. FACTUAL INFORMATION .............................................................................................. 4 1.1 History of the flight ............................................................................................................. -

Interkommunal Kystsoneplan for Evenes, Narvik, Ballangen, Tysfjord Og Hamarøy

Mottaker: Evenes kommune Narvik kommune Ballangen kommune Tysfjord kommune Hamarøy kommune Fauske, 03.8.2019 Følgende organisasjoner har sluttet seg til uttalelsen: • Norsk Ornitologisk Forening avd. Nordland (NOF Nordland) • Norges Jeger- og Fiskerforbund Nordland (NJFF Nordland) • Naturvernforbundet i Nordland Vi beklager sent høringsinnspill, og håper våre merknader blir tatt med. Vi vil uansett følge opp dette i innspillsgruppene og i det videre planarbeid. Innspill til planprogram – interkommunal kystsoneplan for Evenes, Narvik, Ballangen, Tysfjord og Hamarøy Viser til høring av planprogram for interkommunal kystsoneplan for Evenes, Narvik, Ballangen, Tysfjord og Hamarøy. Kommunene har startet en interkommunal planprosess for å utarbeide en kystsoneplan for felles kystområder og fjordsystem. Bakgrunnen for planarbeidet er et ønske om en forutsigbar og bærekraftig forvaltning av sjøarealene. Arbeidet er organisert etter plan- og bygningsloven kapittel 9 interkommunalt plansamarbeid og det er opprettet et eget styre med en politisk valgt representant fra hver kommune. Dette styret har mottatt delegert myndighet fra kommunestyrene/ Bystyret til å varsle oppstart, fastsette planprogram og legge planforslag ut på høring. Endelig planprogram skal fastsettes i september 2019, og endelig vedtak av plan vil være september 2020. Planprosessen bygger på FNs bærekraftsmål og planprogrammet skisserer tre fokusområder for det videre arbeidet med planarbeidet. Dette er: • Akvakultur og fiskeri • Reise - og friluftsliv • Ferdsel __________________________________________________________________________________ forum for Forum for natur og friluftsliv i Nordland natur og Eiaveien 5, 8208 Fauske friluftsliv [email protected] / 90 80 61 46 Nordland www.fnf-nett.no/nordland Org. nr.: 983267998 FNF Nordlands merknader til planprogrammet FNF Nordland viser til de gode uttalelsene fra Narvik og Omegn JFF, Naturvernforbundet i Narvik og slutter oss til disse. -

Utdrag Av Norway Refinery Location Study Av Standard Oil I

NORWAY REFINERY LOCATION STUDY zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA STANDARD OIL COM PANY (N. J.) zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA November 15, 1957 * zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA ACKNOWLEDGEMENT zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA The Committee acknowledges its appreciation of the cooperation and valuable assistance rendered to it by all the experts and the members of their organiza tions who assisted the Committee. These included Mr. G. S. Ronke of the Project Coordinator's Office, Oslo; Captain H. C. Pel I inghom, Mr. E. H. Harding, and Mr. S. H. Meadows-Taylor of Transportation Coordination, London; Mr. Matthew Radom of Employee Relations; Mr. J. Acquaviva, Mr. R.C. Wilson, and Mr. J. E. Lyons of Esso Research and Engineering Company; Mr. Wilhelm Bugge and Mr. Fredrik Bugge, Legal Counsel, Oslo; members of Norske Esso, Svenska Esso, and many others within and without the Jersey organization. Mr. Radom is the author of the Human Relations Section of the report and Captain Fellingham of the Marine Section, for which eoch deserve special commendation. The other portions of the report were prepared by the various Committee members to whom the Committee, as a whole, is likewise indebted. 1 zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA November 15, 1957 Mr. Brian Mead Refining Coordination 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York, New York De^ Mr. Mead: In your letter of February 13, 1957, toMr. C. E. Paules, Mr. D. W. Ramsey, and Mr. J. J. Winterbottom, you asked that a committee be ap- pointed to evaluate potential sites for a new refinery in Norway. The Committee was appointed. Its study of potential sites for this refinery has been made. Out of more than 30 sites studied only two were found acceptable. -

Sommerfeltia 20 G

DOI: 10.2478/som-1993-0006 sommerfeltia 20 G. Mathiassen Corticolous and lignicolous Pyrenomycetes s.lat. (Ascomycetes) on Salixalong a mid-Scandinavian transect 1993 sommerf~ is owned and edited by the Botanical Garden and Museum, University of Oslo. SOMMERFELTIA is named in honour of the eminent Norwegian botanist and clergyman S0ren Christian Sommerfelt (1794-1838). The generic name Sommerfeltia has been used in (1) the lichens by Florke 1827, now Solorina, (2) Fabaceae by Schumacher 1827, now Drepanocarpus, and (3) Asteraceae by Lessing 1832, nom. cons. SOMMERFELTIA is a series of monographs in plant taxonomy, phytogeography, phyto sociology, plant ecology, plant morphology, and evolutionary botany. Most papers are by Norwegian authors. Authors not on the staff of the Botanical Garden and Museum in Oslo pay a page charge of NOK 30. SOMMERFEL TIA appears at irregular intervals, normally one article per volume. Editor: Rune Halvorsen 0kland. Editorial Board: Scientific staff of the Botanical Garden and Museum. Address: SOMMERFELTIA, Botanical Garden and Museum, University of Oslo, Trond heimsveien 23B, N-0562 Oslo 5, Norway. Order: On a standing order (payment on receipt of each volume) SOMMERFELTIA is supplied at 30 % discount. Separate volumes are supplied at prices given on pages inserted at the end of the volume. sommerfeltia 20 G. Mathiassen Corticolous and lignicolous Pyrenomycetes s.lat. (Ascomycetes) on Sa/ix along a mid-Scandinavian transect 1993 This thesis is dedicated to Lennart Holm, Ola Skifte and Finn-Egil Eckblad, three septuagenerian, Nordic mycologists, who have all contributed significantly to its completion. ISBN 82-7420-022-5 ISSN 0800-6865 Mathiassen G.