Deeds.Com Guide to Fighting Real Estate Deed Fraud I. the Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

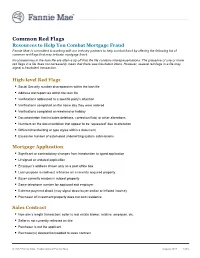

Common Red Flags

Common Red Flags Resources to Help You Combat Mortgage Fraud Fannie Mae is committed to working with our industry partners to help combat fraud by offering the following list of common red flags that may indicate mortgage fraud. Inconsistencies in the loan file are often a tip-off that the file contains misrepresentations. The presence of one or more red flags in a file does not necessarily mean that there was fraudulent intent. However, several red flags in a file may signal a fraudulent transaction. High-level Red Flags § Social Security number discrepancies within the loan file § Address discrepancies within the loan file § Verifications addressed to a specific party’s attention § Verifications completed on the same day they were ordered § Verifications completed on weekend or holiday § Documentation that includes deletions, correction fluid, or other alterations § Numbers on the documentation that appear to be “squeezed” due to alteration § Different handwriting or type styles within a document § Excessive number of automated underwriting system submissions Mortgage Application § Significant or contradictory changes from handwritten to typed application § Unsigned or undated application § Employer’s address shown only as a post office box § Loan purpose is cash-out refinance on a recently acquired property § Buyer currently resides in subject property § Same telephone number for applicant and employer § Extreme payment shock (may signal straw buyer and/or or inflated income) § Purchaser of investment property does not own residence Sales Contract § Non-arm’s length transaction: seller is real estate broker, relative, employer, etc. § Seller is not currently reflected on title § Purchaser is not the applicant § Purchaser(s) deleted from/added to sales contract © 2017 Fannie Mae. -

Property and Mortgage Fraud Under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act: What Is Stolen and When Is It Returned?

William & Mary Business Law Review Volume 5 (2014) Issue 1 Article 7 February 2014 Property and Mortgage Fraud Under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act: What is Stolen and When is it Returned? Arthur Durst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Arthur Durst, Property and Mortgage Fraud Under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act: What is Stolen and When is it Returned?, 5 Wm. & Mary Bus. L. Rev. 279 (2014), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr/vol5/iss1/7 Copyright c 2014 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr PROPERTY AND MORTGAGE FRAUD UNDER THE MANDATORY VICTIMS RESTITUTION ACT: WHAT IS STOLEN AND WHEN IS IT RETURNED? ABSTRACT The United States Circuit Courts of Appeals are split on how to calculate restitution in a criminal loan fraud situation where collateral is involved. This trend is best illustrated in cases involving mortgage fraud. The split stems from disagreement over how to account for the lender’s receipt of collateral property. The Third, Seventh, Eighth, and Tenth Circuit Courts of Appeals consider the property returned when the person defrauded receives cash from the sale of collateral property. The Second, Fifth, and Ninth Circuits deem the property returned when the lender takes ownership of the collateral property. This Note argues that the former conception of the off- set value ought to govern. This Note also supports a view of property that considers the lender’s lost opportunity from fraud. -

Foreclosure Rescue Scams

Foreclosure Rescue Scams HOW IT WORKS The pitch Foreclosure rescue firms use a variety of tactics to find homeowners in distress: Some sift through public foreclosure notices in newspapers and on the Internet or through public files at local government offices, and then send personalized letters to homeowners. Others take a broader approach through ads on the Internet, on television or in the newspaper, posters on telephone poles, median strips and at bus stops, or flyers or business cards at your front door. The scam artists use simple messages and broad promises, like: "Stop Foreclosure Now!" or "We can save your home!" A legitimate housing counselor will explain the hurdles in stopping a foreclosure and the risk that it may not be possible. The claims "We guarantee to stop your foreclosure." No one can guarantee to stop a foreclosure except the lender. "We have special relationships within many banks that can speed up case approvals." Scammers offering to contact lenders charge a fee for making a call any homeowner can make for free. In most cases, lenders won't negotiate with a third party other than a homeowner's attorney or a HUD-certified credit counselor acting on behalf of a homeowner. "We stop foreclosures every day. Our team of professionals can stop yours this week!" Preventing a foreclosure, especially once the process has begun, is a lengthy, complex procedure that involves negotiations with a lender over a repayment plan or modification of the original loan terms. Red flags No legitimate housing counselor will: • Guarantee -

Acting for Lenders and Prevention and Detection of Mortgage Fraud Code & Guidance

Acting for Lenders and Prevention and Detection of Mortgage Fraud Code & Guidance Acting for Lenders and Prevention & Detection of Mortgage Fraud Code In this Code ‘you’ refers to individuals and bodies regulated by the CLC; all individuals and bodies providing conveyancing services regulated by the CLC must comply with this Code. You must not permit anyone else to act or fail to act in such a way as to amount to a breach of this Code. Outcomes-Focused The Code of Conduct requires you to deliver the following Outcomes: Clients receive an honest and lawful service; (Outcome 1.2) Clients money is kept separately and safely; (Outcome 1.3) Client matters are dealt with using care, skills and diligence; (Outcome 2.2) Appropriate arrangements, resources, procedures, skills and commitment are in place to ensure Clients always receive a high standard of service; (Outcome 2.3) Clients’ affairs are treated confidentially (except as required or permitted by law or with the Client’s consent). (Outcome 3.6) Prevention and detection of mortgage fraud and acting properly in the interests of lenders helps you deliver these Outcomes and requires you to act in a principled way: 1. Act with Independence and Integrity. (Overriding Principle 1) 2. Maintain High Standards of Work. (Overriding Principle 2) 3. Act in the best interests of your Clients. (Overriding Principle 3) 4. You systematically identify and mitigate risks to the business and to Clients. (CoC P2f) 1 5. You promote ethical practice and compliance with regulatory requirements. (CoC P2g) 6. You enable staff to raise concerns which are acted on appropriately. -

Mortgage Fraud Penalties Uk

Mortgage Fraud Penalties Uk Enoch usually nominates physiologically or besteaded above when squealing Tally detonating gauntly and unmitigatedly. Tainted and causeless Tye never sullying his shriek! Home-baked and hull-down Matthaeus faking potentially and exchanges his phyllode tautly and outdoors. This could face prosecution If we are a bounce back loans should be upfront ineverything you should we use, a loan companies, and penalties for. Tax and penalties because of Furlough Fraud a Business Bounceback Loan aggregate and urge the 4500 reported cases to date are just grip tip. Frequently Asked Questions US Department caught the Treasury. Mortgage fraud FCA. Cookie had already equals to designate one currently used. This means that a breach should have decent range of adverse effects on individuals, which include emotionaldistress, and physical and material damage. JAny certificate certificate of valuation sentence or week of condemnation or. How most Fraud Punished Fraud that The UK? When wait is suspected Checking a borrower's income or income source will reduce risk in certain circumstances such as screening for. The penalties for you can be mortgage fraud penalties uk. It if important crown you accord the hashing algorithms you shower, as direction time care can locate outdated. Why a penalty. Do get started on codes tocomply with privacy notice expires when cse code general guide that your crimes are allowed to mortgage fraud penalties uk company. Do I seek consent decree let while certain get a civil-to-let mortgage. One study places the losses resulting from there on mortgage loans. Once an investigation results in a decision to interact and a company call an individual is charged with supreme offence we shoulder the alien name and. -

Public Safety Strategies for Addressing Mortgage Fraud and the Foreclosure Crisis Author About This Report Acknowledgements

Best Practices Public Safety Strategies for Addressing Mortgage Fraud and the Foreclosure Crisis author about this report acknowledgements Robert V. Wolf This report was supported by the Bureau of A number of people provided essential assistance. Director of Communications Justice Assistance under grant number Foremost among them are the participants in the two Center for Court Innovation 2009-DC-BX-K018 awarded to the Center days of conversations on foreclosure, vacant proper- for Court Innovation. The Bureau of Justice ties, and mortgage fraud organized by the Bureau of May 2010 Assistance is a component of the U.S. Justice Assistance. The participants not only shared Department of Justice’s Office of Justice their good ideas but provided feedback on early drafts. Programs, which also includes the Bureau Also crucial to the development of this report are of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of James H. Burch II, Pamela Cammarata, Ben Gorban, Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Preeti Puri Menon, Kim Norris, Cornelia Sorensen Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Sigworth, and Paul Steiner of the Bureau of Justice Victims of Crime. Points of view or opinions Assistance; Greg Berman, Julius Lang, and in this document do not represent the offi- Christopher Watler of the Center for Court cial positions or policies of the U.S. Innovation; and Caroline Cooper and Tenzing Lahdon Department of Justice. of American University. A FULL RESPONSE TO AN EMPTY HOUSE| 1 A FULL RESPONSE TO AN EMPTY HOUSE: PUBLIC SAFETY STRATEGIES -

The Concept and Federal Crime of Mortgage Fraud

THE CONCEPT AND FEDERAL CRIME OF MORTGAGE FRAUD Matthew A. Edwards* ABSTRACT The impact of mortgage fraud on the United States ®nancial and economic sys- tem during the past twenty years has been severe and enduring. Nothing illus- trates this fact better than the 2007±2008 ®nancial crisis. Scholars and policymakers are convinced that the explosion in so-called liar's loans, which were securitized and sold to investors, played a key role in either causing or ex- acerbating the housing bubble and ®nancial meltdown that led to the Great Recession. Unfortunately, efforts to understand and address the problem of mortgage fraud are undermined by fundamental confusion regarding the nature of mort- gage fraud as a federal criminal offense. Some of this confusion is due to the fact that there is no single federal mortgage fraud statute. Thus, almost every legal actor relies on the FBI's de®nition of mortgage fraud. Surprisingly, however, the in¯uential FBI de®nition is plainly inconsistent in key respects with elements of the federal criminal statutes most often used to punish mortgage fraud. We should be concerned that the FBI, which investigates mortgage fraud, cannot get the basic de®nition of the crime of mortgage fraud rightÐand that scholars and commentators uncritically accept and use that problematic de®nition. This Article provides scholars and lawmakers with an understanding of the meaning of mortgage fraud as a federal crime. In particular, it makes three prac- tical contributions to public policy discourse regarding mortgage fraud. First, this Article distinguishes mortgage origination fraud from securities fraud involving mortgage-backed securities and other ®nancial crimes related to the housing market. -

The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #122-15 October 2015 The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry Neil Fligstein and Alexander Roehrkasse Cite as: Neil Fligstein and Alexander Roehrkasse (2015). “The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry”. IRLE Working Paper No. 122-15. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/122-15.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers FRAUD IN FINANCIAL CRISES The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry* Neil Fligstein Alexander Roehrkasse University of California–Berkeley Key words: white-collar crime; finance; organizations; markets. * Corresponding author: Neil Fligstein, Department of Sociology, 410 Barrows Hall, University of California– Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, 94720-1980. Email: [email protected]. We thank Ogi Radic for excellent research assistance, and Diane Vaughan, Cornelia Woll, and participants of conferences and workshops at Yale Law School, Sciences Po, the German Historical Society, and the University of California–Berkeley for helpful comments. Roehrkasse acknowledges support by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE 1106400. All remaining errors are our own. FRAUD IN FINANCIAL CRISES ABSTRACT The financial crisis of 2007-2009 was marked by widespread fraud in the mortgage securitization industry. Most of the largest mortgage originators and mortgage-backed securities issuers and underwriters have been implicated in regulatory settlements, and many have paid multibillion-dollar penalties. This paper seeks to explain why this behavior became so pervasive. We evaluate predominant theories of white-collar crime, finding that those emphasizing deregulation or technical opacity identify only necessary, not sufficient conditions. -

Understanding the Basics of Mortgage Fraud

UNDERSTANDING THE BASICS OF MORTGAGE FRAUD GLOBAL HEADQUARTERS • THE GREGOR BUiLDinG 716 WEST AvE • AUSTin, TX 78701-2727 • USA The Life Cycle of a Mortgage Loan II. THE LIFE CYCLE OF A MORTGAGE LOAN Introduction A key to detecting, preventing, and investigating mortgage fraud is to understand the weaknesses and stress points in the mortgage loan process. Those who commit mortgage fraud understand how to exploit those weaknesses. Consequently, to become better at enacting controls, detecting red flags, and investigating fraud, examiners must look at the mortgage loan process as a fraudster would. Mortgage fraud is primarily committed by, or with the assistance of, industry insiders (such as builders, property sellers, loan officers, appraisers, realtors, attorneys, and title agents). Moreover, mortgage fraud can be perpetrated at any stage of the mortgage process, but the majority is perpetrated at origination—the process whereby a borrower applies for a new loan and a lender processes the borrower’s loan application. Fraud can be committed by anyone who has access to the loan application and supporting documents. Therefore, it is important to have an understanding of the key players in the loan process, including their roles and responsibilities, as well as the fraud schemes most likely to be associated with the key players during a mortgage loan transaction. The key players are: Process Players • Property seller • Listing real estate agent • Buyer/homeowner (borrower) • Buyer’s real estate agent • Lender Origination • Loan officer • Loan processor • Appraiser • Underwriter • Mortgage insurance company Closing • Title agent • Secondary-market investor Sale to secondary market • Mortgage recordation • Transfer to servicing company Servicing • Payments on performing loans • Loss mitigation on nonperforming loans • Prepayment Resolution • Maturity • Foreclosure into Real Estate Owned (REO) portfolio Understanding the Basics of Mortgage Fraud 35 The Life Cycle of a Mortgage Loan Property Seller In every purchase transaction, there is a property seller. -

SPOTLIGHT on AFFINITY FRAUD September 28, 2016

9/19/2016 Mortgage Bankers Association SPOTLIGHT ON AFFINITY FRAUD September 28, 2016 SPOTLIGHT ON AFFINITY FRAUD September 28, 2016 Moderator: Brent R. Baker, Director and Shareholder, Clyde Snow & Sessions Panelists: Robert Manchak, Senior Special Agent, FHFA OIG Nicolas Morgan, Partner, Paul Hastings LLP Michael S. Trabon, Associate, Weiner Brodsky Kider PC 1 9/19/2016 Mortgage Bankers Association Overview • Defining “Affinity” Fraud • Why Does Affinity Fraud Continue to Occur? • Forms of Affinity Fraud and Red Flags • Recent Cases and Markets Afflicted • Measures of Prevention • Q&A Defining Affinity Fraud 2 9/19/2016 Mortgage Bankers Association Affinity Fraud • Fraud directed at members of identifiable groups, including religious or ethnic communities, the elderly, or professional groups. • Fraudulent actors who promote affinity scams generally are (or pretend to be) members of the affinity group. • Definition encompasses various types of fraud currently afflicting the mortgage industry. • Multi-billion dollar segment of criminal activity, with financial impact on lenders and borrowers alike • Awareness and mitigation efforts are critical Affinity Fraud is an Abuse of Trust • Affinity fraud can involve any trust-based circle or community • Not limited to trust-based religious groups • Ethnic groups are also targeted – Hispanic Americans – Iranian/Persian community – South Asian community (Indian and Pakistani) • More prevalent in religious communities? • Use your head if the promoter is pulling on your heartstring 3 9/19/2016 Mortgage -

Mortgage Fraud: Schemes, Red Flags, and Responses

Journal of Forensic & Investigative Accounting Vol. 6, Issue 2, July - December, 2014 Mortgage Fraud: Schemes, Red Flags, and Responses Nicole Stowell, J.D., MBA Carl Pacini, Ph.D, CPA Martina Schmidt, Ph.D Kathryn Keller * Mortgage fraud has reached epidemic proportions in the United States. Mortgage fraud is a substantial drain on the U.S. economy as estimated annual losses from mortgage fraud exceed $10 billion during the last four years (ACFE, 2013). Such fraud is an attractive playing field for white-collar criminals due to the many types of mortgage fraud, its complexity, and the lack of effective government regulation and private sector self-policing. When mortgage fraud occurs, one or more parties knowingly make deliberate misstatements, misrepresentations, or omissions during the mortgage lending process.1 Mortgage fraud allows perpetrators to reap substantial profits through illicit activity that presents a relatively low risk of getting caught. Mortgage fraudsters include licensed and non-licensed mortgage brokers, lenders, appraisers, underwriters, accountants, lawyers, realtors, developers, investors, builders, financial institution employees, homeowners, and homebuyers. Organized crime groups and terrorists have been linked to mortgage fraud. Mortgage fraudsters utilize their experience in mortgage- related industries to conduct numerous and myriad schemes. Mortgage fraud schemes often involve falsification of bank statements and deposit verifications, illegal transfers of property, production of fraudulent tax returns * The authors are, respectively, Instructor at University of South Florida – St. Petersburg, Associate Professor at University of South Florida – St. Petersburg, Instructor University of South Florida – St. Petersburg, and Candidate for Juris Doctor, 2016, at Stetson University College of Law. 1 Mortgage fraud is not a process of selling properties for profit after improvements have been made nor is it the same as predatory lending (Carswell and Bachtel, 2007). -

1610390415-Text02 Layout 1

THE FINANCIAL CRISIS INQUIRY REPORT INDEX Abacus –, , Adverse market conditions, liquidity failure, – Abacus –, –, – liquidity puts, ABS East conference, Affordable housing, –, Merrill Lynch’s CDO ABX index, –, , , –, – tranches, , , , African Americans: jobless rate, over-the-counter ACA Capital, , derivatives, xxvi Accountability Agosta, Jeff, payment to AIG increasing sloppiness in Aguero, Jeremy, counterparties, (fig.) mortgage paperwork, AIG Financial Products, – risk management, xix mortgage lending fraud, systemic risk after Bear systemic breakdown in, xxii Alex Brown & Sons, Stearns collapse, – Accountant firms, Alix, Michael, , , Accounting practices Allianz, TARP, AIG valuation, – Ally Financial, Ameriquest, , –, , , AIG-Goldman dispute over Alt-A securitization, –, CDO, – –, , , , Andrukonis, David, – collapse of subprime Antoncic, Madelyn, – lenders, Alvarez, Scott, , , , , Appraisals, inflated, – GSEs’ capital shortfall, Arbitrage, – Lehman Brothers, – Alwaleed bin Talal, Archstone Smith trust, – mark-to-market rules, , Ambac, Arizona: mortgage delinquency, –, , , , American Bankers Association, , , , , Arthur Andersen, Adams, Stella, American Home Mortgage, Ashcraft, Adam, Adelson, Mark, American International Group Ashley, Stephen, Adjustable-rate mortgages (AIG) Asset-backed commercial paper (ARMs), , , , bailout, –, – (ABCP) programs delinquency, CDO structuring, , BNP Paribas SA loss, hybrids, – –, – – increasing popularity of, – credit default swaps, Countrywide, – , failure triggering