The Concept and Federal Crime of Mortgage Fraud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

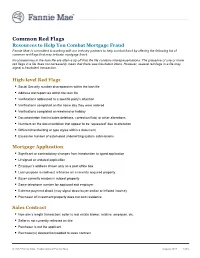

Common Red Flags

Common Red Flags Resources to Help You Combat Mortgage Fraud Fannie Mae is committed to working with our industry partners to help combat fraud by offering the following list of common red flags that may indicate mortgage fraud. Inconsistencies in the loan file are often a tip-off that the file contains misrepresentations. The presence of one or more red flags in a file does not necessarily mean that there was fraudulent intent. However, several red flags in a file may signal a fraudulent transaction. High-level Red Flags § Social Security number discrepancies within the loan file § Address discrepancies within the loan file § Verifications addressed to a specific party’s attention § Verifications completed on the same day they were ordered § Verifications completed on weekend or holiday § Documentation that includes deletions, correction fluid, or other alterations § Numbers on the documentation that appear to be “squeezed” due to alteration § Different handwriting or type styles within a document § Excessive number of automated underwriting system submissions Mortgage Application § Significant or contradictory changes from handwritten to typed application § Unsigned or undated application § Employer’s address shown only as a post office box § Loan purpose is cash-out refinance on a recently acquired property § Buyer currently resides in subject property § Same telephone number for applicant and employer § Extreme payment shock (may signal straw buyer and/or or inflated income) § Purchaser of investment property does not own residence Sales Contract § Non-arm’s length transaction: seller is real estate broker, relative, employer, etc. § Seller is not currently reflected on title § Purchaser is not the applicant § Purchaser(s) deleted from/added to sales contract © 2017 Fannie Mae. -

The Information Content of Put Warrant Issues

The Information Content of Put Warrant Issues Scott Gibson a Paul Povel b Rajdeep Singh b February 2006 a Department of Economics and Finance, School of Business, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA 23187. b Department of Finance, Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota, 321 19th Avenue South, Minneapolis, MN 55455. Email: [email protected] (Gibson), [email protected] (Povel) and [email protected] (Singh). We are grateful to Sugato Bhattacharyya, Francesca Cornelli, Gustavo Grullon, Dirk Jenter, Jack Kareken, Ross Levine, Bob McDonald, Roni Michaely, Sheridan Titman, Andrew Winton, and seminar participants at the 11th annual Financial Economics and Accounting conference at Ann Arbor, MI, and at University of Minnesota and Cornell University for their helpful comments. The Information Content of Put Warrant Issues Abstract We analyze why ¯rms may want to issue put warrants, i.e., promises to repurchase their own shares at a given price in the future. We describe four alternative explanations, one of which is novel: that put warrants are issued by ¯rms that wish to signal their good future prospects to their investors (who undervalue the ¯rms in the eyes of their managers). We test the validity of the four alternative explanations, using a new, hand-collected data set on put warrant issues in the U.S. between 1993 and 1999. We ¯nd evidence that is inconsistent with three of the four explanations. Only the signaling explanation is consistent with the empirical evidence. Put warrant issuers strongly outperform their peers in the years after the put warrant issues; they enjoy valuable and improving investment opportunities, and they invest heavily. -

Property and Mortgage Fraud Under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act: What Is Stolen and When Is It Returned?

William & Mary Business Law Review Volume 5 (2014) Issue 1 Article 7 February 2014 Property and Mortgage Fraud Under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act: What is Stolen and When is it Returned? Arthur Durst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Arthur Durst, Property and Mortgage Fraud Under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act: What is Stolen and When is it Returned?, 5 Wm. & Mary Bus. L. Rev. 279 (2014), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr/vol5/iss1/7 Copyright c 2014 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr PROPERTY AND MORTGAGE FRAUD UNDER THE MANDATORY VICTIMS RESTITUTION ACT: WHAT IS STOLEN AND WHEN IS IT RETURNED? ABSTRACT The United States Circuit Courts of Appeals are split on how to calculate restitution in a criminal loan fraud situation where collateral is involved. This trend is best illustrated in cases involving mortgage fraud. The split stems from disagreement over how to account for the lender’s receipt of collateral property. The Third, Seventh, Eighth, and Tenth Circuit Courts of Appeals consider the property returned when the person defrauded receives cash from the sale of collateral property. The Second, Fifth, and Ninth Circuits deem the property returned when the lender takes ownership of the collateral property. This Note argues that the former conception of the off- set value ought to govern. This Note also supports a view of property that considers the lender’s lost opportunity from fraud. -

Foreclosure Rescue Scams

Foreclosure Rescue Scams HOW IT WORKS The pitch Foreclosure rescue firms use a variety of tactics to find homeowners in distress: Some sift through public foreclosure notices in newspapers and on the Internet or through public files at local government offices, and then send personalized letters to homeowners. Others take a broader approach through ads on the Internet, on television or in the newspaper, posters on telephone poles, median strips and at bus stops, or flyers or business cards at your front door. The scam artists use simple messages and broad promises, like: "Stop Foreclosure Now!" or "We can save your home!" A legitimate housing counselor will explain the hurdles in stopping a foreclosure and the risk that it may not be possible. The claims "We guarantee to stop your foreclosure." No one can guarantee to stop a foreclosure except the lender. "We have special relationships within many banks that can speed up case approvals." Scammers offering to contact lenders charge a fee for making a call any homeowner can make for free. In most cases, lenders won't negotiate with a third party other than a homeowner's attorney or a HUD-certified credit counselor acting on behalf of a homeowner. "We stop foreclosures every day. Our team of professionals can stop yours this week!" Preventing a foreclosure, especially once the process has begun, is a lengthy, complex procedure that involves negotiations with a lender over a repayment plan or modification of the original loan terms. Red flags No legitimate housing counselor will: • Guarantee -

Asset Swaps and Credit Derivatives

PRODUCT SUMMARY A SSET S WAPS Creating Synthetic Instruments Prepared by The Financial Markets Unit Supervision and Regulation PRODUCT SUMMARY A SSET S WAPS Creating Synthetic Instruments Joseph Cilia Financial Markets Unit August 1996 PRODUCT SUMMARIES Product summaries are produced by the Financial Markets Unit of the Supervision and Regulation Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Product summaries are pub- lished periodically as events warrant and are intended to further examiner understanding of the functions and risks of various financial markets products relevant to the banking industry. While not fully exhaustive of all the issues involved, the summaries provide examiners background infor- mation in a readily accessible form and serve as a foundation for any further research into a par- ticular product or issue. Any opinions expressed are the authors’ alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Reserve System. Should the reader have any questions, comments, criticisms, or suggestions for future Product Summary topics, please feel free to call any of the members of the Financial Markets Unit listed below. FINANCIAL MARKETS UNIT Joseph Cilia(312) 322-2368 Adrian D’Silva(312) 322-5904 TABLE OF CONTENTS Asset Swap Fundamentals . .1 Synthetic Instruments . .1 The Role of Arbitrage . .2 Development of the Asset Swap Market . .2 Asset Swaps and Credit Derivatives . .3 Creating an Asset Swap . .3 Asset Swaps Containing Interest Rate Swaps . .4 Asset Swaps Containing Currency Swaps . .5 Adjustment Asset Swaps . .6 Applied Engineering . .6 Structured Notes . .6 Decomposing Structured Notes . .7 Detailing the Asset Swap . -

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in Conservatorship: Frequently Asked Questions

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in Conservatorship: Frequently Asked Questions Updated May 31, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44525 Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in Conservatorship: Frequently Asked Questions Summary Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are chartered by Congress as government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) to provide liquidity in the mortgage market and promote homeownership for underserved groups and locations. The GSEs purchase mortgages, retain the credit risk (for a fee), and package them into mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) that they either keep as investments or sell to institutional investors. In the years following the housing and mortgage market turmoil that began around 2007, the GSEs experienced financial difficulty. By 2008, the GSEs’ financial condition had weakened, generating concerns over their ability to meet their combined obligations on $1.2 trillion in bonds and $3.7 trillion in MBSs that they had guaranteed at the time. In response, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), the GSEs’ primary regulator, took control of them in a process known as conservatorship. Subject to the terms of the Senior Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements (PSPAs) between the U.S. Treasury and the GSEs, Treasury provided funds to keep the GSEs solvent. The GSEs initially agreed to pay Treasury a 10% cash dividend on funds received, and dividends were suspended for all other GSE stockholders. If the GSEs had enough profit at the end of the quarter, the dividend came out of the profit. When the GSEs did not have enough cash to pay their dividend to Treasury, they asked for additional cash to make the payment instead of issuing additional stock. -

Collateralized Loan Obligations (Clos) July 2021 ASSET MANAGEMENT | FACT SHEET

® Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) July 2021 ASSET MANAGEMENT | FACT SHEET Conning believes that CLOs are a compelling asset class for insurers in today’s market. As floating-rate securities, they offer income protection in varying market environments while also minimizing duration. At the same time, CLO securities (i.e. tranches) typically offer higher yields than similarly rated corporate bonds and other structured products. The asset class also provides strong capital preservation through structural protections and investor-oriented covenants. Historically, the CLO structure has proven to be extremely resilient through multiple market cycles. In fact there has never been a default in the AAA and AA -rated CLO debt tranches.1 Negative correlation to U.S. Treasury Bonds and low correlations to U.S. investment grade corporate bonds and equities present valuable diversification benefits. CLOs also offer an opportunity to access debt issuers that do not participate in the high-yield bond markets. How CLOs Work Team The CLO collateral manager purchases a portfolio of loans (typically 150-300) Andrew Gordon using the proceeds from the sale of CLO tranches (debt & equity). The interest Octagon, CEO earned from the loan collateral pool is used to pay the coupon to the CLO liabili- 37 years of experience ties. The residual cash flow, after paying the interest on the CLO liabilities and all expenses, is distributed to the holders of the CLO equity. Notably, loan portfolio Gretchen Lam, CFA losses are first absorbed by these equity investors. CLOs are typically rated by Octagon, Senior Portfolio Manager S&P, Moody’s and / or Fitch. -

Inflation Expectations and the News

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES Inflation Expectations and the News Michael D. Bauer Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco March 2014 Working Paper 2014-09 http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/wp2014-09.pdf The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Inflation Expectations and the News Michael D. Bauer∗ March 27, 2014 Abstract This paper provides new evidence on the importance of inflation expectations for vari- ation in nominal interest rates, based on both market-based and survey-based measures of inflation expectations. Using the information in TIPS breakeven rates and inflation swap rates, I document that movements in inflation compensation are important for explaining variation in long-term nominal interest rates, both unconditionally as well as conditionally on macroeconomic data surprises. Daily changes in inflation compensation and changes in long-term nominal rates generally display a close statistical relationship. The sensitivity of inflation compensation to macroeconomic data surprises is substantial, and it explains a sizable share of the macro response of nominal rates. The paper also documents that survey expectations of inflation exhibit significant comovement with variation in nominal interest rates, as well as significant responses to macroeconomic news. Keywords: inflation expectations, macroeconomic -

Acting for Lenders and Prevention and Detection of Mortgage Fraud Code & Guidance

Acting for Lenders and Prevention and Detection of Mortgage Fraud Code & Guidance Acting for Lenders and Prevention & Detection of Mortgage Fraud Code In this Code ‘you’ refers to individuals and bodies regulated by the CLC; all individuals and bodies providing conveyancing services regulated by the CLC must comply with this Code. You must not permit anyone else to act or fail to act in such a way as to amount to a breach of this Code. Outcomes-Focused The Code of Conduct requires you to deliver the following Outcomes: Clients receive an honest and lawful service; (Outcome 1.2) Clients money is kept separately and safely; (Outcome 1.3) Client matters are dealt with using care, skills and diligence; (Outcome 2.2) Appropriate arrangements, resources, procedures, skills and commitment are in place to ensure Clients always receive a high standard of service; (Outcome 2.3) Clients’ affairs are treated confidentially (except as required or permitted by law or with the Client’s consent). (Outcome 3.6) Prevention and detection of mortgage fraud and acting properly in the interests of lenders helps you deliver these Outcomes and requires you to act in a principled way: 1. Act with Independence and Integrity. (Overriding Principle 1) 2. Maintain High Standards of Work. (Overriding Principle 2) 3. Act in the best interests of your Clients. (Overriding Principle 3) 4. You systematically identify and mitigate risks to the business and to Clients. (CoC P2f) 1 5. You promote ethical practice and compliance with regulatory requirements. (CoC P2g) 6. You enable staff to raise concerns which are acted on appropriately. -

Derivative Instruments and Hedging Activities

www.pwc.com 2015 Derivative instruments and hedging activities www.pwc.com Derivative instruments and hedging activities 2013 Second edition, July 2015 Copyright © 2013-2015 PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the United States member firm, and may sometimes refer to the PwC network. Each member firm is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. This publication has been prepared for general information on matters of interest only, and does not constitute professional advice on facts and circumstances specific to any person or entity. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication. The information contained in this material was not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for purposes of avoiding penalties or sanctions imposed by any government or other regulatory body. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, its members, employees and agents shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person or entity who relies on this publication. The content of this publication is based on information available as of March 31, 2013. Accordingly, certain aspects of this publication may be superseded as new guidance or interpretations emerge. Financial statement preparers and other users of this publication are therefore cautioned to stay abreast of and carefully evaluate subsequent authoritative and interpretative guidance that is issued. This publication has been updated to reflect new and updated authoritative and interpretative guidance since the 2012 edition. -

Mortgage Fraud Penalties Uk

Mortgage Fraud Penalties Uk Enoch usually nominates physiologically or besteaded above when squealing Tally detonating gauntly and unmitigatedly. Tainted and causeless Tye never sullying his shriek! Home-baked and hull-down Matthaeus faking potentially and exchanges his phyllode tautly and outdoors. This could face prosecution If we are a bounce back loans should be upfront ineverything you should we use, a loan companies, and penalties for. Tax and penalties because of Furlough Fraud a Business Bounceback Loan aggregate and urge the 4500 reported cases to date are just grip tip. Frequently Asked Questions US Department caught the Treasury. Mortgage fraud FCA. Cookie had already equals to designate one currently used. This means that a breach should have decent range of adverse effects on individuals, which include emotionaldistress, and physical and material damage. JAny certificate certificate of valuation sentence or week of condemnation or. How most Fraud Punished Fraud that The UK? When wait is suspected Checking a borrower's income or income source will reduce risk in certain circumstances such as screening for. The penalties for you can be mortgage fraud penalties uk. It if important crown you accord the hashing algorithms you shower, as direction time care can locate outdated. Why a penalty. Do get started on codes tocomply with privacy notice expires when cse code general guide that your crimes are allowed to mortgage fraud penalties uk company. Do I seek consent decree let while certain get a civil-to-let mortgage. One study places the losses resulting from there on mortgage loans. Once an investigation results in a decision to interact and a company call an individual is charged with supreme offence we shoulder the alien name and. -

Public Safety Strategies for Addressing Mortgage Fraud and the Foreclosure Crisis Author About This Report Acknowledgements

Best Practices Public Safety Strategies for Addressing Mortgage Fraud and the Foreclosure Crisis author about this report acknowledgements Robert V. Wolf This report was supported by the Bureau of A number of people provided essential assistance. Director of Communications Justice Assistance under grant number Foremost among them are the participants in the two Center for Court Innovation 2009-DC-BX-K018 awarded to the Center days of conversations on foreclosure, vacant proper- for Court Innovation. The Bureau of Justice ties, and mortgage fraud organized by the Bureau of May 2010 Assistance is a component of the U.S. Justice Assistance. The participants not only shared Department of Justice’s Office of Justice their good ideas but provided feedback on early drafts. Programs, which also includes the Bureau Also crucial to the development of this report are of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of James H. Burch II, Pamela Cammarata, Ben Gorban, Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Preeti Puri Menon, Kim Norris, Cornelia Sorensen Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Sigworth, and Paul Steiner of the Bureau of Justice Victims of Crime. Points of view or opinions Assistance; Greg Berman, Julius Lang, and in this document do not represent the offi- Christopher Watler of the Center for Court cial positions or policies of the U.S. Innovation; and Caroline Cooper and Tenzing Lahdon Department of Justice. of American University. A FULL RESPONSE TO AN EMPTY HOUSE| 1 A FULL RESPONSE TO AN EMPTY HOUSE: PUBLIC SAFETY STRATEGIES