Mortgage Fraud: Schemes, Red Flags, and Responses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOW REAL ESTATE SPECULATORS ARE TARGETING NEW YORK CITY’S MOST AFFORDABLE NEIGHBORHOODS by Leo Goldberg and John Baker

HOUSE FLIPPING IN NYC: HOW REAL ESTATE SPECULATORS ARE TARGETING NEW YORK CITY’S MOST AFFORDABLE NEIGHBORHOODS By Leo Goldberg and John Baker JUNE 2018 2 In neighborhoods across New York City, real estate investors are knocking on doors and calling up homeowners, seeking to convince them to sell their properties at low prices so that the homes can be resold for substantial profits. Commonly referred to as “housing flipping,” this practice can uproot residents in gentrifying neighborhoods and reduce the stock of affordable homes in a city where homeownership is increasingly out of reach for most. Not since 2006, when property speculators played a significant role in spurring the mortgage crisis that triggered the Great Recession, has so much house flipping been recorded in the city.1 The practice is often lucrative for investors but can involve unwanted and sometimes deceptive solicitations of homeowners. And the profitability of house flipping creates an incentive for scammers seeking to dislodge vulnerable — and often older — homeowners from their properties.2 In more economically depressed parts of the country, flipping is sometimes considered a boon because it puts dilapidated homes back on the market. However, in New York City, where prices are sky-high and demand for homes far exceeds supply, flipping contributes to gentrification and displacement. The practice not only affects homeowners, but also renters who live in 1-4 unit homes and often pay some of the most affordable rents in the city. Once an investor swoops in, these renters can find they’ve lost their leases as the property gets flipped. -

A Guide to Flipping Mobile Homes Intro Thanks for Purchasing Our Book

A Guide to Flipping Mobile Homes Intro Thanks for purchasing our book. First off, mobile home investing has been a huge asset to our real estate investing portfolio. Especially in times where margins are thinner in asset types like commercial, land, MFH, single family residence, and notes. This isn’t a comprehensive guide by any means. But it is designed for the newcomer in MH’s and/or the wholesaler or flipper who wants to monetize some of the mobile home leads that he/she generates (I know that I left a lot of money on the table when I threw those leads away). It’s also designed for those who are very interested in possibly making anywhere from 20%-50% (or more) return on their money yearly. This niche has many exit strategies for the flipper who wants to make a quick turnover… or the cash flow investor who wants to create a passive income stream. Or for the developer who wants to build a large amount of value in a parcel by planting manufactured homes into them. Whatever your goals are, it can be accomplished with mobile homes. To dive further into the topic and learn specific strategies, then sign up to our email list where we email DAILY tips along with promotional offers to upcoming events, seminars, and information packets at: www.pauldocampo.com Paul do Campo, Millionaire Makers Next Generation DISCLAIMER: We are not financial advisors and do not guarantee any success or return on any investment. The returns and the theories that have been stated here are only just that, theories and do not guarantee a certain return on any investment. -

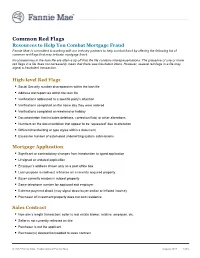

Common Red Flags

Common Red Flags Resources to Help You Combat Mortgage Fraud Fannie Mae is committed to working with our industry partners to help combat fraud by offering the following list of common red flags that may indicate mortgage fraud. Inconsistencies in the loan file are often a tip-off that the file contains misrepresentations. The presence of one or more red flags in a file does not necessarily mean that there was fraudulent intent. However, several red flags in a file may signal a fraudulent transaction. High-level Red Flags § Social Security number discrepancies within the loan file § Address discrepancies within the loan file § Verifications addressed to a specific party’s attention § Verifications completed on the same day they were ordered § Verifications completed on weekend or holiday § Documentation that includes deletions, correction fluid, or other alterations § Numbers on the documentation that appear to be “squeezed” due to alteration § Different handwriting or type styles within a document § Excessive number of automated underwriting system submissions Mortgage Application § Significant or contradictory changes from handwritten to typed application § Unsigned or undated application § Employer’s address shown only as a post office box § Loan purpose is cash-out refinance on a recently acquired property § Buyer currently resides in subject property § Same telephone number for applicant and employer § Extreme payment shock (may signal straw buyer and/or or inflated income) § Purchaser of investment property does not own residence Sales Contract § Non-arm’s length transaction: seller is real estate broker, relative, employer, etc. § Seller is not currently reflected on title § Purchaser is not the applicant § Purchaser(s) deleted from/added to sales contract © 2017 Fannie Mae. -

Real Estate Investing Overview

Real Estate Investing Overview 18301 Von Karman, Suite 330, Irvine, CA 92612 Phone: 800-208-2976 Fax: 949.37.6701 [email protected] Fix and Flip Real Estate Investing Overview Getting Started Wholesaling: Wholesaling is a great way to get started if you are short on experience and/or funds. With wholesaling, your objective is to enter into purchase contracts at an attractive enough purchase price that you can assign your purchase contract to someone who is willing to pay you a premium to your contract purchase amount for the opportunity to purchase the property. Partnering: Partnering with an experienced fix/flip investor is a great way to learn the business with less risk. Your partner will likely want to share in any profits but the potential savings of avoiding snafus may be more than worth any shared profits. Fix and Flipping: The potential profits of going it alone and purchasing, repairing and reselling your own investment property are the greatest, but so are the potential risks. How to Obtain the Money to Flip Houses Do you want to start flipping houses but don’t know how you are going to access the money you need? Check out these options to find the cash to begin flipping houses: Home Equity Loan: You can utilize the equity in your primary residence to flip houses. If you don’t have enough equity in your home to purchase an investment property outright you can leverage your home equity into buying one, or more deals with a traditional or private money lender. Credit Cards: Be cautious when using this method because it’s easy to get over extended. -

Report on Tax Fraud and Money Laundering Vulnerabilities Involving the Real Estate Sector

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT REPORT ON TAX FRAUD AND MONEY LAUNDERING VULNERABILITIES INVOLVING THE REAL ESTATE SECTOR CENTRE FOR TAX POLICY AND ADMINISTRATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report contains information on the tax evasion and money laundering vulnerabilities associated with the real estate sector. The information contained in the report was provided by 18 countries represented in the Sub-Group in response to a questionnaire that was sent to delegates in July 2006. Apart from providing a useful overview of the key tax evasion and money laundering issues and risks associated with the real estate sector, the report is also intended to provide practical guidance to tax authorities that are seeking to implement or refine strategies to effectively address these risks. The key findings are as follows: In most of the countries surveyed, the real estate sector has been identified as an important sector being used to facilitate tax fraud and money laundering. There are no reported official figures or statistics about the dimension of the problem; one country, Austria, has reported an estimation of the amount of fraud involving the real estate sector of approximately € 70 million. The countries reported that the three most common methods and schemes used are: price manipulation (escalating prices make it easier to manipulate prices of properties and transactions), undeclared income / transactions and the use of nominees and/or false identities, and corporations or trusts to hide the identity of the beneficial owners. The method of concealing ownership has three main variations: a) onshore acquisitions through off- shores companies and/or through a complex structure of ownership; b) unreported acquisition of properties overseas; and c) use of nominees. -

Property and Mortgage Fraud Under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act: What Is Stolen and When Is It Returned?

William & Mary Business Law Review Volume 5 (2014) Issue 1 Article 7 February 2014 Property and Mortgage Fraud Under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act: What is Stolen and When is it Returned? Arthur Durst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Arthur Durst, Property and Mortgage Fraud Under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act: What is Stolen and When is it Returned?, 5 Wm. & Mary Bus. L. Rev. 279 (2014), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr/vol5/iss1/7 Copyright c 2014 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr PROPERTY AND MORTGAGE FRAUD UNDER THE MANDATORY VICTIMS RESTITUTION ACT: WHAT IS STOLEN AND WHEN IS IT RETURNED? ABSTRACT The United States Circuit Courts of Appeals are split on how to calculate restitution in a criminal loan fraud situation where collateral is involved. This trend is best illustrated in cases involving mortgage fraud. The split stems from disagreement over how to account for the lender’s receipt of collateral property. The Third, Seventh, Eighth, and Tenth Circuit Courts of Appeals consider the property returned when the person defrauded receives cash from the sale of collateral property. The Second, Fifth, and Ninth Circuits deem the property returned when the lender takes ownership of the collateral property. This Note argues that the former conception of the off- set value ought to govern. This Note also supports a view of property that considers the lender’s lost opportunity from fraud. -

HOME BUYERS SHOP on REMAX.COM Than Any Other National Real Estate Franchise Website

THE ZIZZI TEAM OF RE/MAX PLUS THE Left to right: POWER Pam Cimini, Pete Zizzi, Julie Goin OF A LOCAL MARKET Office Phone: LEADER 585.279.8155 A WORLD Two Convenient Locations: RENOWNED Brighton: 2171 Monroe Ave. | Rochester NY 14618 Greece: 2850 W. Ridge Rd | Rochester NY 14626 Each office independently owned and operated. BRAND 2171 Monroe Ave. Rochester NY 14618. Each office independently owned and operated. MISSION STATEMENT The Zizzi Team is dedicated to guiding our clients and providing them with the highest quality Real Estate services to achieve their goals. Our Commitment: Gaining our client’s trust by facilitating all transactions to a positive and enjoyable outcome based on our client’s best interests. Our Focus: Educating and empowering our clients before, during and after the transaction. Our Services: Executing a balanced combination of cutting edge technology and personal interaction. Our Loyalty: Establishing ourselves as a professional referral source and nurturing client relationships through appreciation programs that continue long term. Our Mission is to continue to be among the top producing Real Estate teams in New York State. The Zizzi Team is united by friendship, strengthened by mutual trust, and bolstered by our common goals in business in personal life. ABOUT THE Office: 585-279-8155 [email protected] ZIZZI TEAM www.ZizziTeam.com Pete Zizzi: Associate Real Estate Broker, Residential Specialist, ABR, MRP • GRAR Platinum Award 2013-Present • RE/MAX 100% Club 2008-Present • #3 Team Gross Closed Commission -2015 -

Flipping Brochure

SPECIAL ALERT Office of the Attorney General, Consumer Protection Division Home Buyers: Beware of “Flipping” Scams Bought by "flipper" Sold to you $24,000 $78,000 February July efore you agree to buy a house, make sure Take Three Steps to BB you’re not dealing with a “flipper.” A flipper Protect Yourself: buys a house cheap and then sells it to an unsus- pecting home buyer for a price that far exceeds its 1 real value. Get the facts. The flipper finds his victims by looking for someone who needs a new place to live but believes he or You can find out how much the house is she can’t afford to buy a home or qualify for a really worth before you sign a contract. mortgage loan. The flipper gets the buyer to trust Don’t just take the seller’s asking price as being a him by promising to put the buyer in a house and fair market price. You need to get the facts your- arrange a mortgage loan even if the buyer has bad self. Ask the seller to complete and sign the credit or little money. Not surprisingly, these attached “seller’s statement” form. buyers often feel that the flipper is making their ➠ dreams come true by getting them a house and a SEE SELLER’S STATEMENT FORM INSIDE loan when no one else could. The seller’s answers will give you the facts you The flipper does not tell the buyer that the sales need to begin to find out what the true value of price of the house is much higher than the house is the house is. -

Existing and Potential Remedies for Illegal Flipping in Buffalo, New York

Existing and Potential Remedies for Illegal Flipping in Buffalo, New York Written by Scott Mancuso April 15, 2008 University at Buffalo Law School http://bflo-housing.wikispaces.com/ Table of Contents: Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction to Flipping in Buffalo …………………………..………………………… 4 Litigation already brought against flippers in Buffalo …………………………………. 8 An alternative option in Buffalo involving the Housing Court …………..……………. 15 Mortgage Fraud as a nationwide Strategy ………………………………………………17 Why has there not been more action against illegal flippers in Buffalo? ……………… 18 Remedy for bringing more action against illegal flippers in Buffalo ………………….. 20 In Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………... 24 Key Sources ……………………………………………………………………………. 26 Appendices ……………………………………………………………………………... 27 2 Executive Summary: The City of Buffalo should amend the documents used at the annual In Rem foreclosure auction to require more information from bidders and purchasers under penalty of perjury, thereby making it easier to detect, deter, and punish parties interested in purchasing properties to illegally flip them. There are already more abandoned houses in the City of Buffalo than it can even keep track of. These houses lower property values of surrounding homes in already distressed neighborhoods and in turn, lower tax revenues for the city. Abandoned houses also invite vandalism, drug users and squatters. They pose a threat in the form of potential instances of arson and cost the city millions of dollars in demolition expenses. Houses become abandoned for many reasons, but one is that they sometimes fall into the hands of illegal flippers. Unlike legal flippers, illegal flippers generally spend no further money on a property, make fraudulent misrepresentations as to its value, and sell it for a higher price to an unsuspecting buyer. -

Foreclosure Rescue Scams

Foreclosure Rescue Scams HOW IT WORKS The pitch Foreclosure rescue firms use a variety of tactics to find homeowners in distress: Some sift through public foreclosure notices in newspapers and on the Internet or through public files at local government offices, and then send personalized letters to homeowners. Others take a broader approach through ads on the Internet, on television or in the newspaper, posters on telephone poles, median strips and at bus stops, or flyers or business cards at your front door. The scam artists use simple messages and broad promises, like: "Stop Foreclosure Now!" or "We can save your home!" A legitimate housing counselor will explain the hurdles in stopping a foreclosure and the risk that it may not be possible. The claims "We guarantee to stop your foreclosure." No one can guarantee to stop a foreclosure except the lender. "We have special relationships within many banks that can speed up case approvals." Scammers offering to contact lenders charge a fee for making a call any homeowner can make for free. In most cases, lenders won't negotiate with a third party other than a homeowner's attorney or a HUD-certified credit counselor acting on behalf of a homeowner. "We stop foreclosures every day. Our team of professionals can stop yours this week!" Preventing a foreclosure, especially once the process has begun, is a lengthy, complex procedure that involves negotiations with a lender over a repayment plan or modification of the original loan terms. Red flags No legitimate housing counselor will: • Guarantee -

UNLV IGI Japan

Practical Perspectives on Gambling Regulatory Processes for Study by Japan: Eliminating Organized Crime in Nevada Casinos US Japan Business Council | August 25, 2017 Jennifer Roberts, J.D. Brett Abarbanel, Ph.D. Bo Bernhard, Ph.D. With Contributions from André Wilsenach, Breyen Canfield, Ray Cho, 1 and Thuon Chen Practical Perspectives on Gambling Regulatory Processes for Study by Japan: Eliminating Organized Crime in Nevada Casinos Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Report Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Review of the Legalization of Casino Gaming in Nevada ............................................. 4 Gambling Legalization in Nevada – The (Not So) Wild West ................................................... 4 Nevada’s Wide-Open Gambling Bill .......................................................................................... 5 Developing The Strip – The Mob Moves In ............................................................................... 6 A Turning Point – The Kefauver Hearings and Aftermath ......................................................... 7 Nevada’s Corporatization Phase ............................................................................................... 10 Remnants of the Mob and Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal ................................................................ 11 Eliminating -

Download Full Book

Vegas at Odds Kraft, James P. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Kraft, James P. Vegas at Odds: Labor Conflict in a Leisure Economy, 1960–1985. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.3451. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/3451 [ Access provided at 25 Sep 2021 14:41 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Vegas at Odds studies in industry and society Philip B. Scranton, Series Editor Published with the assistance of the Hagley Museum and Library Vegas at Odds Labor Confl ict in a Leisure Economy, 1960– 1985 JAMES P. KRAFT The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2010 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Mary land 21218- 4363 www .press .jhu .edu Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kraft, James P. Vegas at odds : labor confl ict in a leisure economy, 1960– 1985 / James P. Kraft. p. cm.—(Studies in industry and society) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 8018- 9357- 5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN- 10: 0- 8018- 9357- 7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Labor movement— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 2. Labor— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 3. Las Vegas (Nev.)— Economic conditions— 20th century. I. Title. HD8085.L373K73 2009 331.7'6179509793135—dc22 2009007043 A cata log record for this book is available from the British Library.