African American Abolitionists Research List

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Framework for Teaching American Slavery

K–5 FRAMEWORK TEACHING HARD HISTORY A FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHING AMERICAN SLAVERY ABOUT THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER The Southern Poverty Law Center, based in Montgomery, Alabama, is a nonpar- tisan 501(c)(3) civil rights organization founded in 1971 and dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry, and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of society. ABOUT TEACHING TOLERANCE A project of the Southern Poverty Law Center founded in 1991, Teaching Tolerance is dedicated to helping teachers and schools prepare children and youth to be active participants in a diverse democracy. The program publishes Teaching Tolerance magazine three times a year and provides free educational materials, lessons and tools for educators commit- ted to implementing anti-bias practices in their classrooms and schools. To see all of the resources available from Teaching Tolerance, visit tolerance.org. © 2019 SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER Teaching Hard History A K–5 FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHING AMERICAN SLAVERY 2 TEACHING TOLERANCE // TEACHING HARD HISTORY // A FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHING AMERICAN SLAVERY CONTENTS Introduction 4 About the Teaching Hard History Elementary Framework 6 Grades K-2 10 Grades 3-5 18 Acknowledgments 28 Introduction Teaching about slavery is hard. It’s especially hard in elementary school classrooms, where talking about the worst parts of our history seems at odds with the need to motivate young learners and nurture their self-confidence. Teaching about slavery, especially to children, challenges educators. Those we’ve spoken with—especially white teachers—shrink from telling about oppression, emphasizing tales of escape and resistance instead. They worry about making black students feel ashamed, Latinx and Asian students feel excluded and white students feel guilty. -

Black Citizenship, Black Sovereignty: the Haitian Emigration Movement and Black American Politics, 1804-1865

Black Citizenship, Black Sovereignty: The Haitian Emigration Movement and Black American Politics, 1804-1865 Alexander Campbell History Honors Thesis April 19, 2010 Advisor: Françoise Hamlin 2 Table of Contents Timeline 5 Introduction 7 Chapter I: Race, Nation, and Emigration in the Atlantic World 17 Chapter II: The Beginnings of Black Emigration to Haiti 35 Chapter III: Black Nationalism and Black Abolitionism in Antebellum America 55 Chapter IV: The Return to Emigration and the Prospect of Citizenship 75 Epilogue 97 Bibliography 103 3 4 Timeline 1791 Slave rebellion begins Haitian Revolution 1831 Nat Turner rebellion, Virginia 1804 Independent Republic of Haiti declared, Radical abolitionist paper The Liberator with Jean-Jacques Dessalines as President begins publication 1805 First Constitution of Haiti Written 1836 U.S. Congress passes “gag rule,” blocking petitions against slavery 1806 Dessalines Assassinated; Haiti divided into Kingdom of Haiti in the North, Republic of 1838 Haitian recognition brought to U.S. House Haiti in the South. of Representatives, fails 1808 United States Congress abolishes U.S. 1843 Jean-Pierre Boyer deposed in coup, political Atlantic slave trade chaos follows in Haiti 1811 Paul Cuffe makes first voyage to Africa 1846 Liberia, colony of American Colonization Society, granted independence 1816 American Colonization Society founded 1847 General Faustin Soulouque gains power in 1817 Paul Cuffe dies Haiti, provides stability 1818 Prince Saunders tours U.S. with his 1850 Fugitive Slave Act passes U.S. Congress published book about Haiti Jean-Pierre Boyer becomes President of 1854 Martin Delany holds National Emigration Republic of Haiti Convention Mutiny of the Holkar 1855 James T. -

American Free Blacks and Emigration to Haiti

#33 American Free Blacks and Emigration to Haiti by Julie Winch University of Massachusetts, Boston Paper prepared for the XIth Caribbean Congress, sponsored by the Caribbean Institute and Study Center for Latin America (CISCLA) of Inter American University, the Department of Languages and Literature of the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, and the International Association of Comparative Literature, held in Río Piedras March 3 and 5, in San Germán March 4, 1988 August 1988 El Centro de Investigaciones Sociales del Caribe y América Latina (CISCLA) de la Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico, Recinto de San Germán, fue fundado en 1961. Su objetivo fundamental es contribuir a la discusión y análisis de la problemática caribeña y latinoamericana a través de la realización de conferencias, seminarios, simposios e investigaciones de campo, con particular énfasis en problemas de desarrollo político y económico en el Caribe. La serie de Documentos de Trabajo tiene el propósito de difundir ponencias presentadas en actividades de CISCLA así como otros trabajos sobre temas prioritarios del Centro. Para mayor información sobre la serie y copias de los trabajos, de los cuales existe un número limitado para distribución gratuita, dirigir correspondencia a: Dr. Juan E. Hernández Cruz Director de CISCLA Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico Apartado 5100 San Germán, Puerto Rico 00683 The Caribbean Institute and Study Center for Latin America (CISCLA) of Inter American University of Puerto Rico, San Germán Campus, was founded in 1961. Its primary objective is to make a contribution to the discussion and analysis of Caribbean and Latin American issues. The Institute sponsors conferences, seminars, roundtable discussions and field research with a particular emphasis on issues of social, political and economic development in the Caribbean. -

The PAS and American Abolitionism: a Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War

The PAS and American Abolitionism: A Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War By Richard S. Newman, Associate Professor of History Rochester Institute of Technology The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was the world's most famous antislavery group during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, although not as memorable as many later abolitionists (from William Lloyd Garrison and Lydia Maria Child to Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth), Pennsylvania reformers defined the antislavery movement for an entire generation of activists in the United States, Europe, and even the Caribbean. If you were an enlightened citizen of the Atlantic world following the American Revolution, then you probably knew about the PAS. Benjamin Franklin, a former slaveholder himself, briefly served as the organization's president. French philosophes corresponded with the organization, as did members of John Adams’ presidential Cabinet. British reformers like Granville Sharp reveled in their association with the PAS. It was, Sharp told told the group, an "honor" to be a corresponding member of so distinguished an organization.1 Though no supporter of the formal abolitionist movement, America’s “first man” George Washington certainly knew of the PAS's prowess, having lived for several years in the nation's temporary capital of Philadelphia during the 1790s. So concerned was the inaugural President with abolitionist agitation that Washington even shuttled a group of nine slaves back and forth between the Quaker State and his Mount Vernon home (still, two of his slaves escaped). The PAS was indeed a powerful abolitionist organization. PAS Origins The roots of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society date to 1775, when a group of mostly Quaker men met at a Philadelphia tavern to discuss antislavery measures. -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

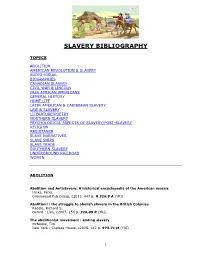

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

© 2019 Kaisha Esty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2019 Kaisha Esty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “A CRUSADE AGAINST THE DESPOILER OF VIRTUE”: BLACK WOMEN, SEXUAL PURITY, AND THE GENDERED POLITICS OF THE NEGRO PROBLEM 1839-1920 by KAISHA ESTY A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the co-direction of Deborah Gray White and Mia Bay And approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey MAY 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “A Crusade Against the Despoiler of Virtue”: Black Women, Sexual Purity, and the Gendered Politics of the Negro Problem, 1839-1920 by KAISHA ESTY Dissertation Co-Directors: Deborah Gray White and Mia Bay “A Crusade Against the Despoiler of Virtue”: Black Women, Sexual Purity, and the Gendered Politics of the Negro Problem, 1839-1920 is a study of the activism of slave, poor, working-class and largely uneducated African American women around their sexuality. Drawing on slave narratives, ex-slave interviews, Civil War court-martials, Congressional testimonies, organizational minutes and conference proceedings, A Crusade takes an intersectional and subaltern approach to the era that has received extreme scholarly attention as the early women’s rights movement to understand the concerns of marginalized women around the sexualized topic of virtue. I argue that enslaved and free black women pioneered a women’s rights framework around sexual autonomy and consent through their radical engagement with the traditionally conservative and racially-exclusionary ideals of chastity and female virtue of the Victorian-era. -

The Port Royal Journal of Charlotte L. Forten, 1862-1863

THE JOURNAL OF NEGRO HISTO RY VOL. XXXV-July, 1950-No. 3 A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT: THE PORT ROYAL JOURNAL OF CHARLOTTE L. FORTEN, 1862-1863. Charlotte L. Forten, the author of the following Jour- nal, was born of free Negro parents in Philadelphia in 1838, the granddaughter of James Forten, wealthy sail- maker and abolitionist,' and the daughter of Robert Bridges Forten. Her father, a staunch enemy of prejudice,2 re- fused to subject her to the segregated schools of her native city, sending her instead to Salem, Massachusetts, when she 1 Accounts of James Forten 's important contributions to antislavery will be found in Lydia Maria Child, The Freedmen's Book (Boston, 1865), 100- 103; William C. Nell, Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (Boston, 1855), 166-169; Robert Purvis, Remarks on the Life and Character of James Forten, Delivered at Bethel Church, March 30, 1842 (Philadelphia, 1842); and nmorebriefly in the Dictionary of American Biography (New York, 1928-1937), VI, 536-537. 2Robert Bridges Forten was so opposed to discrimination that he re- peatedly threatened to leave the United States for Canada. Just before the Civil War he did move to England, only to return and enlist as a private in the Forty-Third United States Colored Regiment. He died while in recruiting service in Maryland, and was buried with full military honors. Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5 (Harrisburg, 1868-1871), V, 1084. The Liberator, May 13, 1864, contains an account of his life and a description of his funeral. 233 234 JOURNALOF NEGROHISTORY was sixteeni years old. -

But One Race: the Life of Robert Purvis. by MARGARET HOPE BACON. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007. Xi, 279 Pp

2008 BOOK REVIEWS 103 But One Race: The Life of Robert Purvis. By MARGARET HOPE BACON. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007. xi, 279 pp. Ancestral chart, notes, bibliography, index. $35.) With emancipation scholars looking north (New York) and south (Haiti) of abolitionist Pennsylvania, Margaret Hope Bacon’s wonderful biography of Robert Purvis is most welcome. One of the leading, though underrated, reformers of the nineteenth-century, Purvis (1810–98) dedicated his long life to achieving black equality. Though born free in South Carolina to an English father and a mixed-race mother, he remained in Pennsylvania for nearly seven decades after moving there as a teenager in the 1820s. Despite the fact that the Quaker state’s gradual abolition law had existed nearly as long as American independence, the meaning of emancipation remained a hotly debated issue. As Bacon shows in a fast-paced and enjoyable narrative, Purvis was a consistent voice of black freedom, assuming the mantle of protest established by the postrevolutionary generation of African American leaders that included his father-in-law, the famed sailmaker James Forten. In short, this is no mere biography of a neglected reformer but a study of northern postemancipation society leading up to the Civil War era. It should not be overlooked. Although Purvis was light-skinned, educated, and wealthy—easily able to “pass” in white society—he always identified himself as “black.” And black Pennsylvanians were increasingly marginalized in antebellum culture, no matter their elite status. Long before southern society created segregated schools and streetcars, free blacks faced such discrimination in the Quaker state. -

December 26, 1848: Ellen and William Craft Escape Slavery Learn More

December 26, 1848: Ellen and William Craft Escape Slavery Learn More Suggested Readings R. J. M. Blackett, Beating Against the Barriers: Biographical Essays in Nineteenth-Century Afro- American History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986). Sarah Brusky, "The Travels of William and Ellen Craft: Race and Travel Literature in the Nineteenth Century," Prospects 25 (2000): 177-91. William and Ellen Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom: The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999). Barbara McCaskill, "Ellen Craft: The Fugitive Who Fled as a Planter," in Georgia Women: Their Lives and Times, vol. 1., ed. Ann Short Chirhart and Betty Wood (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009). Barbara McCaskill, "'Yours Very Truly': Ellen Craft—The Fugitive as Text and Artifact," African American Review 28 (winter 1994). Ellen Samuels, "'A Complication of Complaints': Untangling Disability, Race, and Gender in William and Ellen Craft's Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom," MELUS 31 (fall 2006): 15-47. Dorothy Sterling, Black Foremothers: Three Lives (Old Westbury, N.Y.: Feminist Press, 1998). Daneen Wardrop, "Ellen Craft and the Case of Salomé Muller in Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom," Women's Studies 33 (2004): 961-84. “William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-622&sug=y Georgia Women of Achievement: http://www.georgiawomen.org/2010/10/craft-ellen-smith/ “Voices From the Gap.” University of Minnesota. http://voices.cla.umn.edu/artistpages/craftEllen.php Documenting the American South: http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/craft/menu.html Stories of the Fugitive Slaves. -

Pennsylvania Colonization Society As an Agent of Emancipation

Rethinking Northern White Support for the African Colonization Movement: The Pennsylvania Colonization Society as an Agent of Emancipation N 1816 WHITE REFORMERS WHO HOPED to transport black Americans to Africa established the American Colonization Society (ACS). Over the next ten years, the ACS founded the colony of Liberia and organized scores of state and local auxiliary associations across the United States. Among these was the Pennsylvania Colonization Society (PCS), which was formed in 1826. For those PCS supporters who envisioned the group sending the Keystone State's black population to Liberia, decades of disappointment were forthcoming. Between 1820 and 1860 the number of African Americans in Pennsylvania grew from thirty thousand to fifty-seven thousand. During the same period, less than three hundred of the state's black residents moved to Africa. The PCS nevertheless remained a vibrant and conspic- uous institution. But if the organization rarely sent black Pennsylvanians to Liberia, what did it do to advance the colonization cause?' 1 The standard work on the ACS is P. J. Staudenraus, The African Colonization Movement, 1816-1865 (New York, 1961). For black Pennsylvanians, see Joe William Trotter Jr. and Eric Ledell Smith, eds., African Americans in Pennsylvania: Shifting HistoricalPerspectives (University Park, Pa., 1997); Julie Winch, Philadelphia'sBlack Elite: Activism, Accommodation, and the Struggle for Autonomy, 1787-1848 (Philadelphia, 1988); and Julie Winch, ed., The Elite of Our People:Joseph Willson's Sketches of Black Upper-Class Life in Antebellum Philadelphia (University Park, Pa., 2000). On nineteenth-century Liberia, see Tom W. Shick, Behold the Promised Land: A History of Afro-American Settler Society in Nineteen th-Century Liberia (Baltimore,' 1980). -

December 26, 1848: Ellen and William Craft Escape Slavery

December 26, 1848: Ellen and William Craft Escape Slavery Daily Activity Introduction: The daily activities created for each of the Today in Georgia History segments are designed to meet the Georgia Performance Standards for Reading Across the Curriculum, and Grade Eight: Georgia Studies. For each date, educators can choose from three optional activities differentiated for various levels of student ability. Each activity focuses on engaging the student in context specific vocabulary and improving the student’s ability to communicate about historical topics. One suggestion is to use the Today in Georgia History video segments and daily activities as a “bell ringer” at the beginning of each class period. Using the same activity daily provides consistency and structure for the students and may help teachers utilize the first 15-20 minutes of class more effectively. Optional Activities: Level 1: Provide the students with the vocabulary list and have them use their textbook, a dictionary, or other teacher provided materials to define each term. After watching the video, have the students write a complete sentence for each of the vocabulary terms. Student created sentences should reflect the meaning of the word based on the context of the video segment. Have students share a sampling of sentences as a way to check for understanding. Level 2: Provide the students with the vocabulary list for that day’s segment before watching the video and have them guess the meaning of each word based on their previous knowledge. The teacher may choose to let the students work alone or in groups. After watching the video, have the students revise their definitions to better reflect the meaning of the words based on the context of the video. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

FREE IN THOUGHT, FETTERED IN ACTION: ENSLAVED ADOLESCENT FEMALES IN THE SLAVE SOUTH By COURTNEY A. MOORE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Courtney A. Moore 2 To my parents, Brenda W. Moore and George Moore, my first teachers, and my wonderful family in North Carolina and Florida, my amazing village 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the course of this process I have received the support of countless individuals who have tirelessly given of themselves to make my dream a reality. Professionally, many teachers and professors have shaped my intellectual growth, equipping me with the skills and confidence needed to excel academically. I would like to thank the faculty and staff at Southwood Elementary, Central Davidson Middle and Central Davidson High Schools, especially Ms. Dorothy Talbert. Since elementary school Ms. Talbert encouraged me to conquer my fears and move toward the wonderful opportunities life held, even up to her untimely passing this year she was a constant source of encouragement and cheer. I am also indebted to the Department of History at North Carolina Central University, specifically Drs. Carlton Wilson, Lydia Lindsey and Freddie Parker. Observing these amazing scholars, I learned professionalism, witnessed student-centered teaching at its best, and had the embers of my love for history erupt into an unquenchable fire as I learned of black men and women who impacted the world. My sincerest gratitude to the History Department and African American Studies Program faculty and staff at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.