Bartonian-Priabonian Larger Benthic Foraminiferal Events in the Western Tethys______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palaeogene Marine Stratigraphy in China

LETHAIA REVIEW Palaeogene marine stratigraphy in China XIAOQIAO WAN, TIAN JIANG, YIYI ZHANG, DANGPENG XI AND GUOBIAO LI Wan, X., Jiang, T., Zhang, Y., Xi, D. & Li G. 2014: Palaeogene marine stratigraphy in China. Lethaia, Vol. 47, pp. 297–308. Palaeogene deposits are widespread in China and are potential sequences for locating stage boundaries. Most strata are non-marine origin, but marine sediments are well exposed in Tibet, the Tarim Basin of Xinjiang, and the continental margin of East China Sea. Among them, the Tibetan Tethys can be recognized as a dominant marine area, including the Indian-margin strata of the northern Tethys Himalaya and Asian- margin strata of the Gangdese forearc basin. Continuous sequences are preserved in the Gamba–Tingri Basin of the north margin of the Indian Plate, where the Palaeogene sequence is divided into the Jidula, Zongpu, Zhepure and Zongpubei formations. Here, the marine sequence ranges from Danian to middle Priabonian (66–35 ma), and the stage boundaries are identified mostly by larger foraminiferal assemblages. The Paleocene/Eocene boundary is found between the Zongpu and Zhepure forma- tions. The uppermost marine beds are from the top of the Zongpubei Formation (~35 ma), marking the end of Indian and Asian collision. In addition, the marine beds crop out along both sides of the Yarlong Zangbo Suture, where they show a deeper marine facies, yielding rich radiolarian fossils of Paleocene and Eocene. The Tarim Basin of Xinjiang is another important area of marine deposition. Here, marine Palae- ogene strata are well exposed in the Southwest Tarim Depression and Kuqa Depres- sion. -

Changing Paleo-Environments of the Lutetian to Priabonian Beds of Adelholzen (Helvetic Unit, Bavaria, Germany) 80 ©Geol

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt Jahr/Year: 2011 Band/Volume: 85 Autor(en)/Author(s): Gebhardt Holger, Darga Robert, Coric Stjepan, diverse Artikel/Article: Changing paleo-environments of the Lutetian to Priabonian beds of Adelholzen (Helvetic Unit, Bavaria, Germany) 80 ©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at Berichte Geol. B.-A., 85 (ISSN 1017-8880) – CBEP 2011, Salzburg, June 5th – 8th Changing paleo-environments of the Lutetian to Priabonian beds of Adelholzen (Helvetic Unit, Bavaria, Germany) Holger Gebhardt1, Robert Darga2, Stjepan Ćorić1, Antonino Briguglio3, Elza Yordanova1, Bettina Schenk3, Erik Wolfgring3, Nils Andersen4, Winfried Werner5 1 Geologische Bundesanstalt, Neulinggasse 38, A-1030 Wien, Austria 2 Naturkundemuseum Siegsdorf, Auenstr. 2, D-83313 Siegsdorf, Germany 3 Universität Wien, Erdwiss. Zentrum, Althanstraße 14, A-1090 Wien, Austria 4 Leibniz Laboratory, Universität Kiel, Max-Eyth-Str. 11, D-24118 Kiel, Germany 5 Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie, Richard-Wagner-Str. 10, D-80333 München, Germany The Adelholzen Section is located southwest of Siegsdorf in southern Bavaria, Germany. The section covers almost the entire Lutetian and ranges into the Priabonian. It is part of the Helvetic (tectonic) Unit and represents the sedimentary processes that took place on the southern shelf to upper bathyal of the European platform at that time. Six lithologic units occur in the Adelholzen-Section: 1) marly, glauconitic sands with predominantly Assilina, 2) marly bioclastic sands with predominantly Nummulites, 3) glauconitic sands, 4) marls with Discocyclina, 5) marly brown sand. These units were combined as “Adelholzener Schichten” and can be allocated to the Kressenberg Formation. -

Climatic Shifts Drove Major Contractions in Avian Latitudinal Distributions Throughout the Cenozoic

Climatic shifts drove major contractions in avian latitudinal distributions throughout the Cenozoic Erin E. Saupea,1,2, Alexander Farnsworthb, Daniel J. Luntb, Navjit Sagooc, Karen V. Phamd, and Daniel J. Fielde,1,2 aDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, OX1 3AN Oxford, United Kingdom; bSchool of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Clifton, BS8 1SS Bristol, United Kingdom; cDepartment of Meteorology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden; dDivision of Geological and Planetary Sciences, Caltech, Pasadena, CA 91125; and eDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, CB2 3EQ Cambridge, United Kingdom Edited by Nils Chr. Stenseth, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, and approved May 7, 2019 (received for review March 8, 2019) Many higher level avian clades are restricted to Earth’s lower lati- order avian historical biogeography invariably recover strong evi- tudes, leading to historical biogeographic reconstructions favoring a dence for an origin of most modern diversity on southern land- Gondwanan origin of crown birds and numerous deep subclades. masses (2, 6, 11). However, several such “tropical-restricted” clades (TRCs) are repre- The crown bird fossil record has unique potential to reveal sented by stem-lineage fossils well outside the ranges of their clos- where different groups of birds were formerly distributed in deep est living relatives, often on northern continents. To assess the time. Fossil evidence, for example, has long indicated that total- drivers of these geographic disjunctions, we combined ecological group representatives of clades restricted to relatively narrow niche modeling, paleoclimate models, and the early Cenozoic fossil geographic regions today were formerly found in different parts of record to examine the influence of climatic change on avian geo- – graphic distributions over the last ∼56 million years. -

Paleontology, Stratigraphy, Paleoenvironment and Paleogeography of the Seventy Tethyan Maastrichtian-Paleogene Foraminiferal Species of Anan, a Review

Journal of Microbiology & Experimentation Review Article Open Access Paleontology, stratigraphy, paleoenvironment and paleogeography of the seventy Tethyan Maastrichtian-Paleogene foraminiferal species of Anan, a review Abstract Volume 9 Issue 3 - 2021 During the last four decades ago, seventy foraminiferal species have been erected by Haidar Salim Anan the present author, which start at 1984 by one recent agglutinated foraminiferal species Emirates Professor of Stratigraphy and Micropaleontology, Al Clavulina pseudoparisensis from Qusseir-Marsa Alam stretch, Red Sea coast of Egypt. Azhar University-Gaza, Palestine After that year tell now, one planktic foraminiferal species Plummerita haggagae was erected from Egypt (Misr), two new benthic foraminiferal genera Leroyia (with its 3 species) Correspondence: Haidar Salim Anan, Emirates Professor of and Lenticuzonaria (2 species), and another 18 agglutinated species, 3 porcelaneous, 26 Stratigraphy and Micropaleontology, Al Azhar University-Gaza, Lagenid and 18 Rotaliid species. All these species were recorded from Maastrichtian P. O. Box 1126, Palestine, Email and/or Paleogene benthic foraminiferal species. Thirty nine species of them were erected originally from Egypt (about 58 %), 17 species from the United Arab Emirates, UAE (about Received: May 06, 2021 | Published: June 25, 2021 25 %), 8 specie from Pakistan (about 11 %), 2 species from Jordan, and 1 species from each of Tunisia, France, Spain and USA. More than one species have wide paleogeographic distribution around the Northern and Southern Tethys, i.e. Bathysiphon saidi (Egypt, UAE, Hungary), Clavulina pseudoparisensis (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Arabian Gulf), Miliammina kenawyi, Pseudoclavulina hamdani, P. hewaidyi, Saracenaria leroyi and Hemirobulina bassiounii (Egypt, UAE), Tritaxia kaminskii (Spain, UAE), Orthokarstenia nakkadyi (Egypt, Tunisia, France, Spain), Nonionella haquei (Egypt, Pakistan). -

New Chondrichthyans from Bartonian-Priabonian Levels of Río De Las Minas and Sierra Dorotea, Magallanes Basin, Chilean Patagonia

Andean Geology 42 (2): 268-283. May, 2015 Andean Geology doi: 10.5027/andgeoV42n2-a06 www.andeangeology.cl PALEONTOLOGICAL NOTE New chondrichthyans from Bartonian-Priabonian levels of Río de Las Minas and Sierra Dorotea, Magallanes Basin, Chilean Patagonia *Rodrigo A. Otero1, Sergio Soto-Acuña1, 2 1 Red Paleontológica Universidad de Chile, Laboratorio de Ontogenia y Filogenia, Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Las Palmeras 3425, Santiago, Chile. [email protected] 2 Área de Paleontología, Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Casilla 787, Santiago, Chile. [email protected] * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Here we studied new fossil chondrichthyans from two localities, Río de Las Minas, and Sierra Dorotea, both in the Magallanes Region, southernmost Chile. In Río de Las Minas, the upper section of the Priabonian Loreto Formation have yielded material referable to the taxa Megascyliorhinus sp., Pristiophorus sp., Rhinoptera sp., and Callorhinchus sp. In Sierra Dorotea, middle-to-late Eocene levels of the Río Turbio Formation have provided teeth referable to the taxa Striatolamia macrota (Agassiz), Palaeohypotodus rutoti (Winkler), Squalus aff. weltoni Long, Carcharias sp., Paraorthacodus sp., Rhinoptera sp., and indeterminate Myliobatids. These new records show the presence of common chondrichtyan diversity along most of the Magallanes Basin. The new record of Paraorthacodus sp. and P. rutoti, support the extension of their respective biochrons in the Magallanes Basin and likely in the southeastern Pacific. Keywords: Cartilaginous fishes, Weddellian Province, Southernmost Chile. RESUMEN. Nuevos condrictios de niveles Bartoniano-priabonianos de Río de Las Minas y Sierra Dorotea, Cuenca de Magallanes, Patagonia Chilena. Se estudiaron nuevos condrictios fósiles provenientes de dos localidades, Río de Las Minas y Sierra Dorotea, ambas en la Región de Magallanes, sur de Chile. -

A Rapid Clay-Mineral Change in the Earliest Priabonian of the North Sea Basin?

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences / Geologie en Mijnbouw 83 (3): 179-185 (2004) A rapid clay-mineral change in the earliest Priabonian of the North Sea Basin? R. Saeys, A. Verheyen & N. Vandenberghe1 K.U. Leuven, Historical Geology, Redingenstraat 16, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium 1 corresponding author: [email protected] Manuscript received: February 2004; accepted: August 2004 Abstract In the Eocene to Oligocene transitional strata in Belgium, clay mineral associations vary in response to the climatic evolution and to tectonic pulses. Decreasing smectite to illite ratios and the systematic occurrence of illite-smectite irregular interlayers are consequences of a cooling climate. A marked increase in kaolinite content occurs just after a major unconformity formed at the Bartonian/Priabonian boundary and consequently is interpreted as resulting from the breakdown of uplifted saprolites. Keywords: clay minerals, Paleogene, North Sea Basin Introduction Stratigraphy of the Eocene to Oligocene in the southern North Sea The International Geological Correlation Program Project No 124 integrated the Cenozoic stratigraphic The study of the cored Doel 2b well, north of data of the North Sea Basin, which were dispersed at Antwerp in Belgium, has documented the Bartonian, that time in the literature, and the traditions of the Priabonian and Early Rupelian transition layers by different countries around the North Sea (Vinken, lithostratigraphy, nannoplankton and dinoflagellate 1988). Since this study, it has become known that biostratigraphy, -

USGS Open-File Report 2007-1047, Short Research Paper 035, 3 P.; Doi:10.3133/Of2007-1047.Srp035

U.S. Geological Survey and The National Academies; USGS OF-2007-1047, Short Research Paper 035; doi:10.3133/of2007-1047.srp035 New 40Ar/39Ar and K/Ar ages of dikes in the South Shetland Islands (Antarctic Peninsula) S. Kraus,1 M. McWilliams,2 and Z. Pecskay3 1Instituto Antártico Chileno, Punta Arenas, Chile ([email protected]) 2John de Laeter Centre of Mass Spectrometry, Perth, Australia ([email protected]) 3Institute of Nuclear Research of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Debrecen, Hungary ([email protected]) Abstract Eighteen plagioclase 40Ar/39Ar and 7 whole rock K/Ar ages suggest that dikes in the South Shetland Islands (Antarctic Peninsula) are of Paleocene to Eocene age. The oldest dikes are exposed on Hurd Peninsula (Livingston Island) and do not yield 40Ar/39Ar plateaux. Our best estimates suggest dike intrusion at about the Cretaceous/Paleogene boundary. An older age limit for the dikes is established by Campanian nannofossil ages from their metasedimentary host. Dike intrusion began earlier and lasted longer on Hurd Peninsula (Danian to Priabonian) than on King George Island (Thanetian to Lutetian). Arc magmatism on King George Island, possibly accompanied also by hypabyssal intrusions, began in the Cretaceous as indicated by ages from the stratiform volcanic sequence. The dikes on King George Island were emplaced beginning in the late Paleocene and ending 47–45 Ma. The youngest arc-related dikes on Hurd Peninsula were emplaced ~37 Ma. Citation: Kraus, S., M. McWilliams, and Z. Pecskay (2007), New 40Ar/39Ar and K/Ar ages of dikes in the South Shetland Islands (Antarctic Peninsula), in Antarctica: A Keystone in a Changing World – Online Proceedings of the 10th ISAES, edited by A. -

The Planktonic Foraminifera of the Jurassic. Part III: Annotated Historical Review and References

Swiss J Palaeontol (2017) 136:273–285 DOI 10.1007/s13358-017-0130-0 The planktonic foraminifera of the Jurassic. Part III: annotated historical review and references Felix M. Gradstein1,2 Received: 21 February 2017 / Accepted: 3 April 2017 / Published online: 7 July 2017 Ó Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz (SCNAT) 2017 Abstract Over 70 publications on Jurassic planktonic With few exceptions, Jurassic planktonic foraminifera foraminifera, particularly by East and West European and publications based on thin-sections are not covered in this Canadian micropalaeontologists, are summarized and review. Emphasis is only on thin-section studies that had briefly annotated. It provides an annotated historic over- impact on our understanding of Jurassic planktonic for- view for this poorly understood group of microfossils, aminifera. By the same token, microfossil casts do not going back to 1881 when Haeusler described Globigerina allow study of the taxonomically important wall structure helvetojurassica from the Birmenstorfer Schichten of and sculpture; reference to such studies is limited to few of Oxfordian age in Canton Aargau, Switzerland. historic interest. The first four, presumably planktonic foraminiferal spe- Keywords Jurassic Á Planktonic foraminifera Á Annotated cies from Jurassic strata, were described in the second half of historical review 1881–2015 the nineteenth century: Globigerina liasina from the Middle Lias of France (Terquem and Berthelin 1875), G. helveto- jurassica from the Early Oxfordian of Switzerland (Haeusler Annotated historical overview 1881, 1890) and G. oolithica and G. lobata from the Bajocian of France (Terquem 1883). Some descriptions were from Jurassic planktonic foraminifera have been studied since the internal moulds. It was not until 1958 (see below) that more second half of the nineteen’s century, but it was not until after attention was focused on the occurrences of early planktonic the Second World War that micropalaeontological studies foraminifera, with emphasis on free specimens. -

Planktonic Foraminifera) from the Middle- Upper Eocene of Jabal Hafit, United Arab Emirates

Open access e-Journal Earth Science India eISSN: 0974 – 8350 Vol. 11 (II), April, 2018, pp. 122 - 132 http://www.earthscienceindia.info/ Hantkeninidae (Planktonic Foraminifera) from the Middle- Upper Eocene of Jabal Hafit, United Arab Emirates Haidar Salim Anan Gaza P. O. Box 1126, Palestine Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Six species of the planktonic foraminiferal Family Hantkeninidae belonging to the genera namely Cribrohantkenina and Hantkenina are recorded and described from the Middle- and Upper Eocene succession of Jabal Hafit, Al Ain area, United Arab Emirates. The species include Cribrohantkenina inflata, Hantkenina alabamensis, H. compressa, H. australis, H. liebusi and H. primitiva. The three species of Hantkenina named last are recorded for the first time from the UAE. Keywords: Middle Eocene, Upper Eocene, Hantkeninidae species, United Arab Emirates INTRODUCTION The species of the genera Cribrohantkenina and Hantkenina have a worldwide distribution encircling low and mid-latitudes. The appearance of the genus Hantkenina at 49 Ma corresponds with the Early/Middle Eocene boundary, and their extinction at 33.7 Ma denotes the Eocene/Oligocene boundary, while the genus Cribrohantkenina appears only at the Late Eocene (36. 4 Ma-34. 3 Ma) and its extinction denotes the Eocene/Oligocene boundary. Pearson (1993) noted that the genus Hantkenina have a rounded periphery and more globose chambers (e.g. H. alabamensis) and sometimes areal apertures on the chamber face around the primer aperture (=Cribrohantkenina). Coxall et al. (2003); Coxall and Pearson (2006); and Rögl and Egger (2010) noted that the genus Hantkenina evolved gradually from the genus Clavigerinella in the earliest Middle Eocene, contrary to the long- held view that it is related to the genus Pseudohastigerina evolved from Globanomalina luxorensis (Nakkady) in the earliest Early Eocene (base of Zone E2) by the development of a symmetrical umbilical aperture and slightly asymmetrical to fully planispiral test as are the result of changes in the timing of the development processes. -

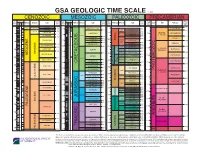

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

Origin and Morphology of the Eocene Planktonic Foraminifer Hantkenina

Journal of Foraminiferal Research, v. 33, no. 3, p. 237—261, July 2003 ORIGIN AND MORPHOLOGY OF THE EOCENE PLANKTONIC FORAMINIFER HANTKENINA HELEN K. COXALL,1 BRIAN T. HUBER,2 AND PAUL N. PEARSON3 ABSTRACT tion, in Pearson, 1993), intimating that the evolution of Hantkenina involved gradual morphological transition. Due Study of the origin and early evolution of the tubu- to the scarcity of Hantkenina near its first appearance level lospine-bearing planktonic foraminiferal genus Hant- and a shortage of suitable stratigraphic records of appropri- kenina reveals that it evolved gradually from the clavate ate age, these assertions have been difficult to substantiate species Clavigerinella eocanica in the earliest middle Eo- and the details of the origination and probable ancestor have cene and is unrelated to the genus Pseudohastigerina. not been satisfactorily demonstrated. The major hypotheses Clavigerinella eocanica and the lower middle Eocene that have been proposed to explain Hantkenina phylogeny species Hantkenina nuttalli share many morphologic fea- are presented in Figure 1. tures and show similar developmental patterns but differ Here we present an investigation into the origin of significantly in these aspects from P. micra. Rare, tran- Hantkenina and its evolutionary relationships with other sitional Clavigerinella-Hantkenina forms from the Hel- Eocene planktonic foraminifera using stratigraphic re- vetikum section of Austria bridge the gap between cla- cords that were unavailable to earlier workers. By using vate and tubulospinose morphologies, providing direct, comparative morphologic observations, ontogenetic mor- stratigraphically-ordered evidence of the evolutionary phometric analysis, stable isotopes, and documenting transition between Hantkenina and Clavigerinella. Cla- rare, transitional hantkeninid material from Austria, we vigerinellid ancestry is traced to a previously unde- demonstrate that Hantkenina is a monophyletic taxon that scribed low-trochospiral species, Parasubbotina eoclava evolved by gradual transition from the genus Clavigeri- sp. -

Palaeogeographic Controls on the Climate System

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Clim. Past Discuss., 11, 5683–5725, 2015 www.clim-past-discuss.net/11/5683/2015/ doi:10.5194/cpd-11-5683-2015 CPD © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 11, 5683–5725, 2015 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Climate of the Past (CP). Palaeogeographic Please refer to the corresponding final paper in CP if available. controls on the climate system Palaeogeographic controls on climate and D. J. Lunt et al. proxy interpretation Title Page D. J. Lunt1, A. Farnsworth1, C. Loptson1, G. L. Foster2, P. Markwick3, C. L. O’Brien4,5, R. D. Pancost6, S. A. Robinson4, and N. Wrobel3 Abstract Introduction 1School of Geographical Sciences, and Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1SS, Conclusions References UK Tables Figures 2Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton, and National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, SO14 3ZH, UK 3Getech Plc, Leeds, LS8 2LJ, UK J I 4Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX1 3AN, UK J I 5Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA 6School of Chemistry, and Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TS, UK Back Close Received: 16 November 2015 – Accepted: 1 December 2015 – Published: 14 December 2015 Full Screen / Esc Correspondence to: D. J. Lunt ([email protected]) Printer-friendly Version Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Interactive Discussion 5683 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract CPD During the period from approximately 150 to 35 million years ago, the Cretaceous– Paleocene–Eocene (CPE), the Earth was in a “greenhouse” state with little or no ice at 11, 5683–5725, 2015 either pole.