Polymorphic Urban Landscapes: the Case of New Songdo City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Joongang Ilbo – Home&] a University Campus? No, It's an International School to Debut in Incheon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8581/joongang-ilbo-home-a-university-campus-no-its-an-international-school-to-debut-in-incheon-258581.webp)

[Joongang Ilbo – Home&] a University Campus? No, It's an International School to Debut in Incheon

[JoongAng Ilbo – home&] A university campus? No, it’s an international school to debut in Incheon Tip: How does an international school differ from a foreign school? Chadwick International, which will open this fall, is an international school. To be more precise, it is a foreign educational institution, which differs from a foreign school. Unlike an international school, which will debut for the first time in the nation, there are some 20 foreign schools in Seoul alone. As for admission, an international school can accept local students up to 30% of its quota while a foreign school can only admit locals who have lived overseas for over three years. Also, a local school corporation is eligible to set up a foreign school while an international school is only established by a foreign education school corporation. A reporter visited Chadwick International, with a couple of experts specializing school architecture. A prestigious foreign private institution has finally arrived in Korea. And that is Chadwick International in Songdo International City that has been established, in accordance with “The Special Laws on Establishment and Operations of Foreign Educational Institution.” Its annual tuition fees reach more than KRW 30 million, and its unique building structure and design seems to be a grand preview of what to be offered. “The school has been designed to facilitate our primary education goal through the state-of-art facility features and carefully- customized classrooms for kids,” R. Warmington, President and CEO of Chadwick International, said. Most prestigious private education institutions stress that education starts from the very stage, at which a school building is designed, not from the school curriculum. -

Choosing the Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing the Right Location

Choosing The Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing The Right Location Geography The Korean Peninsula lies in the north-eastern part of the Asian continent. It is bordered to the north by Russia and China, to the east by the East Sea and Japan, and to the west by the Yellow Sea. In addition to the mainland, South Korea comprises around 3,200 islands. At 99,313 sq km, the country is slightly larger than Austria. It has one of the highest population densities in the world, after Bangladesh and Taiwan, with more than 50% of its population living in the country’s six largest cities. Korea has a history spanning 5,000 years and you will find evidence of its rich and varied heritage in the many temples, palaces and city gates. These sit alongside contemporary architecture that reflects the growing economic importance of South Korea as an industrialised nation. In 1948, Korea divided into North Korea and South Korea. North Korea was allied to the, then, USSR and South Korea to the USA. The divide between the two countries at Panmunjom is one of the world’s most heavily fortified frontiers. Copyright © 2013 IMA Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Generated from http://www.southkorea.doingbusinessguide.co.uk/the-guide/choosing-the-right- location/ Tuesday, September 28, 2021 Choosing The Right Location Page 2 of 4 Surrounded on three sides by the ocean, it is easy to see how South Korea became a world leader in shipbuilding. Climate South Korea has a temperate climate, with four distinct seasons. Spring, from late March to May, is warm, while summer, from June to early September is hot and humid. -

The True School

Avenuel, December 2011 The True School “Be a good person, not just a good student.” This is a phrase that was found written in a classroom of Chadwick International in Songdo, Incheon. After spending a day at Chadwick International, I realized once again how education can play an important part in shaping one‟s life. After driving on the 3rd Gyeongin Highway from Gangnam for about 40 minutes, you will arrive at Chadwick International, established in Songdo International City. As the largest foreign education facility in Korea, Chadwick International is a global educational institution with its main campus in California, United States. As I stepped onto the campus, I remembered the saying, „the starting point of education that prestigious private schools believe in begins from the design of its building.‟ While looking at the school‟s clean and beautiful facilities built on a 14,000 pyeong land, I could also see that the school put in a considerable amount of effort to accommodate the students. The building with facilities such as gymnasiums, swimming pools, and auditoriums is located between the elementary school building and the middle and high school building to minimize the movement of students. In spaces between these buildings, there are gardens and places to rest. What impressed me is that they used glass plates for walls and roofs to let sunlight pass through classes, aisles, and stairs inside the buildings. Rays of warm sunlight in late fall fell onto the students who were circled around a teacher during a class. Such sight can warm anyone‟s heart. -

The 2051 Project Report

Addressing the Dual Challenge Why CAIS Schools Must Ensure Academic Innovation + Build Sustainable Business Plans October 14, 2015 CAIS The 2051 Project Report Dear Colleagues, CAIS depends on volunteers and staff who share their passion for our mission, vision and values. The 2051 Project is fortunate to work with education and business leaders challenging us to think in new ways about the future of independent education. Advisors to The 2051 Project: Jeff Chisholm, Past Chair, St Andrew’s College Rob Cruikshank, CAIS Board Chair David Hadden, CAIS Strategic Advisor Patricia McDermott, CAIS Board Member Jennifer Riel, Associate Director, Rotman School of Management, U of T Meena Roberts, Chair, Ashbury College Dan Sheehan, Vice-Chair, SMUS Presenters at the July 2015 Victoria Meeting: Jennifer Riel – “Design Thinking Sprint!” Rob Cruickshank – “We Need to Change” Anne-Marie Kee – “The ‘WHY’ of Project 2051” Dan Pontefract, Chief Envisioner, TELUS – “What Corporate Canada Needs From K-12” Chris Dede, Timothy E. Wirth Professor in Learning Technologies at Harvard's Graduate School of Education – “Emerging Technologies, Policy, and Leadership” David Hadden – “Innovating at the Board Level” Dan Sheehan – “Innovating for the Win-Win” Thank you to our facilitators – Justin Medved, Director of Learning, Innovation and Technology at The York School; and Garth Nichols, Director of Teaching and Learning at Bayview Glen School – who kept us on track and pushed us to think critically, collaboratively and creatively. Their commitment to The 2051 Project encouraged participants to think differently, engage in thought-provoking research, and begin building a toolkit of innovative ideas for all CAIS schools. And thank you to Fiona Parke, Coordinator of The 2051 Project. -

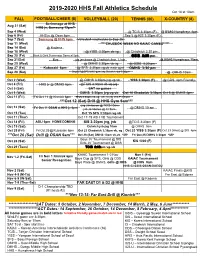

2019-2020 HHS Fall Athletics Schedule

2019-2020 HHS Fall Athletics Schedule Oct 14 at 10am FALL FOOTBALL/CHEER (8) VOLLEYBALL (20) TENNIS (20) X-COUNTRY (8) Aug 31 (Sat) -------------------------------- Scrimmage at HHS -------------------------------HHS jv, Samsung 12pm? Sep 4 (Wed) --------------------------- @ TCIS 3:30pm (F) -----------------------------@ USAG Humphreys 4pm Sep 6 (Fri) ---------------------------- HHS jv @ Osan 6pm ------------------------------- Sep 5 @ KIS 3:30pm (F) Sep 7 (Sat) ------------------------------ Samsung @ HHS 6pm ------------------------------------- Volleyball reschedule to Sep 25 Sep 11 (Wed) ---------------------------------------------------------- ****CHUSEOK WEEK NO KAIAC GAMES***** Sep 14 (Sat) --------------@ Kadena Sep 18 (Wed) -----------------------------@ YISS 3:30pm vb-vg --------------------------- @ Chadwick 3:30 pm Sep 20 (Fri) ---------------------------------------Black & Gold Scrimmage Game at 5pm ----------------------GSIS 3:30 pm Sep 21(Sat) ----------Bye ----------------------------------------- jvg jamboree @ Chadwick 9am, 11am ------------------------------- @ USAG Humphreys 10am Sep 25 (Wed) -------------------------------- @ DMHS 3:30pm vb-vg -----------------------@ GSIS 3:30 pm Sep 27 (Fri) ----------------------Kubasaki 6pm --------------------------------------@ SFS 3:30pm vg-vb main gym -----------------------------OMHS- 3:30--- pm ---------- Sep 28 (Sat) ------------------------------------------------- Sept 27@SFS UAC gym jvg, Dulwich, jvb 3:30pm ---------------------@ OMHS 10am 5pm Oct 2 (Wed) --------------------------------- -

Chadwick International Contents 02 03

CHADWICK INTERNATIONAL CONTENTS 02 03 >> Here in this Country School both boys and girls may find excellent instruction, Contents plenty of outdoor life, and good companions. – MARGARET LEE CHADWICK, School Founder (from the original hornbook posted on the school gates) 04 History of Chadwick 05 Founding principles 06 Mission statement 08 A community of mutual respect and trust 10 A talented, dedicated faculty 12 Superior educational facilities 14 The Village School (Pre-Kindergarten, Kindergarten~Grade 5) 16 The Middle School (Grades 6~8) 18 The Upper School (Grades 9~12) 20 Athletics and physical education 22 Visual and performing arts 24 Outdoor education 26 Service and action 28 Preparation for college 30 Applying to Chadwick International HISTORY OF CHADWICK 04 05 FOUNDING PRINCIPLES History of Chadwick Founding Principles 1935 Margaret Lee Chadwick founds Chadwick Open-Air School in her San Pedro home with four students, two of them her own children. 1938 The Palos Verdes campus of Chadwick Seaside School opens thanks to generous MARGARET LEE CHADWICK donations of land from the Vanderlip family School Founder and buildings from the Roessler family. Seventy-five day and boarding students attend. 1935, Margaret Lee Chadwick established a school at her home in San Pedro with just four 1940 Chadwick graduates its first class In consisting of 6 boys and 5 girls. students. She dedicated Chadwick School to the development of the whole child — character, well-being 1963 Commander and Margaret Lee Chadwick and intellect. She also wanted girls and boys of all races, retire after 28 years of service to the school. -

DMHS Connections

DMHS Connections Dear Students, Parents, and our Area IV Community. As the Principal of Daegu Middle High School, I could not be prouder to serve the Area IV Military Community!This year will be full of firsts as we move into our new 21st Century building and add the middle school to our new campus. It is also a year when our teachers fully implement DoDEA's College and Career Ready Language Arts and Mathematics Standards. We are also looking forward to new standards in social studies,fine arts and science. Our teachers have engaged in continuous staff development training that will position them to deliver the highest quality instruction to all students. This year, we will continue our school goal of improving our writing skills, but will be looking at our data to see if our school improvement focus needs to change as we integrate the middle school. Our new building is getting its final cleaning as we await the delivery of our new technology and furniture. The building is designed to support 21st education and learning. Our students need to be curious, agile, and adaptable. Many of the jobs or careers they will choose may not currently exist. They must master critical thinking and problem solving skills and be able to effectively communicate orally and in writing. They must be able to work collaboratively and access and analyze information. We fully understand the benefits when students can read, write, and comprehend, think critically, collaborate, and create. These skills, part of 21st Century skills, focus on the needed critical competencies for college and career success now and in the next century. -

Doing Business in South Korea H T U O S

Produced by Doing Business in South Korea k u . o c . e d i u G s s e n i s u B g n i o D . a e r o K h t u o S . Seogang Bridge, Seoul, South Korea w w w www. SouthKorea .Doing Business Guide .co.uk Visit the Website and download the free Mobile App South_Korea:master 08/08/2014 14:38 Page 1 CONTENTS 5 South Korea Overview 7 Foreword from Scott Wightman, British Ambassador to the Republic of Korea 9 Introduction from UKTI Deputy Director of Trade South Korea, Andrew Dalgleish 11 Foreword from David Lee, Chief Executive Officer of the British Chamber of Commerce in Korea 12 About International Market Advisor (IMA) 13 About UK Trade & Investment (UKTI) 14 Download the free Mobile App. 15 About this Guide 17 Why South Korea 23 Researching The Market 29 Choosing The Right Location 35 Business Opportunities 51 Establishing The Right Presence 59 Getting Started 69 Business Issues And Considerations 79 South Korean Culture 86 British Embassy South Korea 89 Contact Details 90 Useful Links 91 Additional Useful Links 91 Trade Shows 93 Map of South Korea 94 Disclaimer 95 Quick Facts www. SouthKorea .Doing Business Guide .co.uk 3 South_Korea:master 08/08/2014 14:38 Page 2 For Your successful Business in Korea Our Services We are proud of our distinct services that provide clients with comprehensive solutions by one expert, which is called “one client one expert” . That means that our assigned professional CPA takes full responsibility for clients’ requests . -

Ssatb Member Schools in the United States Arizona

SSATB MEMBER SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES ALABAMA CALIFORNIA Indian Springs School Adda Clevenger Pelham, AL San Francisco, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 4084 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1110 Saint Bernard Preparatory School, Inc. All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cullman, AL Carmel, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 6350 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1209 ARKANSAS Athenian School Danville, CA Subiaco Academy SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1414 Subiaco, AR SSAT Score Recipient Code: 7555 Bay School of San Francisco San Francisco, CA ARIZONA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1500 Fenster School Bentley School Tucson, AZ Lafayette, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 3141 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1585 Orme School Besant Hill School of Happy Valley Mayer, AZ Ojai, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5578 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 3697 Phoenix Country Day School Brandeis Hillel School Paradise Valley, AZ San Francisco, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5767 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1789 Rancho Solano Preparatory School Branson School Glendale, AZ Ross, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5997 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 4288 Verde Valley School Buckley School Sedona, AZ Sherman Oaks, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 7930 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1945 Castilleja School Palo Alto, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2152 Cate School Dunn School Carpinteria, CA Los Olivos, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2170 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2914 Cathedral School for Boys Fairmont Private Schools ‐ Preparatory San Francisco, CA Academy SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2212 Anaheim, CA SSAT Score Recipient -

Application for Admission

Dear Parent, Thank you for your interest in Chadwick International School. We know that choosing a school for your child is one of the most important decisions you will ever make, so we encourage you to learn all you can about our values, our programs and our people. In this booklet you will find an application for the 2011-2012 school year and all of the necessary accompanying information. Chadwick may be best understood through a personal visit, so please make note of the admission events we have scheduled for interested families. The goal of these programs is to provide you with an opportunity to meet our faculty, students and administrators and gain a sense of our unique and exciting community. If you would like to learn more about us, please visit our website at www.chadwickinternational.org or you may call us at (032) 250-5030/5031 ([email protected]). We look forward to hearing from you! Sincerely, Soleiman Dias, Director of Admissions MISSION STATEMENT Chadwick International, the Songdo campus of Chadwick School, and ethnic diversity and by individuals who possess varying kinds which wasl founded in 1935, is dedicated to academic excellence of and degrees of intellectual, artistic and physical abilities; and to the development of self-confident individuals of exemplary By stressing high academic standards and a strong commitment to character. Students are prepared through experience and self-dis- the process of learning; covery to accept the responsibilities inherent in personal freedom By creating an environment for learning that is stimulating, inno- and to contribute positively to contemporary society. -

Virtual Festivals Partner School Listing

Virtual festivals partner school listing 2020-2021 Western Europe U N I T E D K I N G D O M S C H O O L S U N I T E D K I N G D O M A R T I S T S LONDON Helen Abbott Richard Free Jo Parish Sarah Alborn Christina Fulcher Julia Roberts ACS Cobham International School Anna Andresen Sophie Galton Chris Salisbury ACS Egham International School Becky Applin Aileen Gonsalves Tom Scott ACS Hillingdon International School Dinos Aristidou Emily Jane Grant Oliver Senton American School in London Matt Baker Joanna (Joey) Holden Sydney Smith Dwight School London Rebecca Bell Fenella Kelly Helen Szymzcak Halcyon London International School Simon Bell Will Kerley Jess Thorpe International School of London Pete Benson Debra Kidd Ben Vardy King Alfred School Louise Clark Sacha Kyle Georgia White Marymount International School London Jane Coulston Helen Leblique Chris Craig James Lehmann OTHER CITIES Mary-Frances Dargan Tim Licata Calderdale Theatre School, Calderdale Kirstie Davis Odette MacKenzie King William's College, Isle of Man Natalie Diddams Nicola Murray TASIS - United Kingdom, Thorpe Matt Douglas Laurie Neall Kat Fletcher Robin Paley Yorke Southern and Western Europe F R A N C E P O R T U G A L S W I T Z E R L A N D PARIS L I S B O N G E N E V A American School of Paris Carlucci American Institut Le Rosey International School of Lisbon International School of Geneva, La Chataigneraie St Julian's School OTHER CITIES International School of Geneva, LGB International School of Bearn International School of Lausanne International School of S P A -

Global Admissions Profile2016-17

GLOBAL GLOBAL ADMISSIONS2016-17 ADMISSIONS PROFILE 2016-17 PROFILE PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG ISBN 978-988-8314-86-7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Publisher. PRINTED IN HONG KONG THE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG THE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG 2 WELCOME TO HKU CONTENTS 4 HONG KONG HAS IT ALL 6 THE TOP CHOICE FOR TOP STUDENTS 14 IMPACT UNIVERSITY: INTERNATIONALISATION 22 HKU: ASIA'S GLOBAL UNIVERSITY 24 IMPACT UNIVERSITY: INNOVATION 28 IMPACT UNIVERSITY: INTERDISCIPLINARITY 30 CAREER OPPORTUNITIES ABOUND 34 EMBRACING DIVERSITY 38 HKU ADMISSIONS AROUND THE WORLD 40 SUPPORTIVE SCHOLARSHIPS 44 HKU: MAKING AN IMPACT WELCOME to HKU Professor Peter Mathieson is the President and Vice-Chancellor of HKU. He will be leaving HKU in 2018 to take up a similar post elsewhere. In this last Global Admissions Profile for him, he talks about some of the achievements of HKU under his leadership, and HKU's plans for developing these strengths further. The University of Hong Kong (HKU) is already considered one and student or staff-led events promoting understanding of diverse more than league tables: we believe we can improve further. All this is made possible and enhanced by Hong Kong’s unique of the most international universities in the world, but we are not cultures, foods, music and dance etc; and secondly via our place in the world. We are at the gateway to China and Greater satisfi ed.