Draft Environmental Assessment PROPOSED FISH BARRIER in HOT SPRINGS CANYON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana Chiricahuensis)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana chiricahuensis) Final Recovery Plan April 2007 CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Rana chiricahuensis) RECOVERY PLAN Southwest Region U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and are sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director, or Director, as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature citation of this document should read as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana chiricahuensis) Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Southwest Region, Albuquerque, NM. 149 pp. + Appendices A-M. Additional copies may be obtained from: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Field Office Southwest Region 2321 West Royal Palm Road, Suite 103 500 Gold Avenue, S.W. -

Edna Assay Development

Environmental DNA assays available for species detection via qPCR analysis at the U.S.D.A Forest Service National Genomics Center for Wildlife and Fish Conservation (NGC). Asterisks indicate the assay was designed at the NGC. This list was last updated in June 2021 and is subject to change. Please contact [email protected] with questions. Family Species Common name Ready for use? Mustelidae Martes americana, Martes caurina American and Pacific marten* Y Castoridae Castor canadensis American beaver Y Ranidae Lithobates catesbeianus American bullfrog Y Cinclidae Cinclus mexicanus American dipper* N Anguillidae Anguilla rostrata American eel Y Soricidae Sorex palustris American water shrew* N Salmonidae Oncorhynchus clarkii ssp Any cutthroat trout* N Petromyzontidae Lampetra spp. Any Lampetra* Y Salmonidae Salmonidae Any salmonid* Y Cottidae Cottidae Any sculpin* Y Salmonidae Thymallus arcticus Arctic grayling* Y Cyrenidae Corbicula fluminea Asian clam* N Salmonidae Salmo salar Atlantic Salmon Y Lymnaeidae Radix auricularia Big-eared radix* N Cyprinidae Mylopharyngodon piceus Black carp N Ictaluridae Ameiurus melas Black Bullhead* N Catostomidae Cycleptus elongatus Blue Sucker* N Cichlidae Oreochromis aureus Blue tilapia* N Catostomidae Catostomus discobolus Bluehead sucker* N Catostomidae Catostomus virescens Bluehead sucker* Y Felidae Lynx rufus Bobcat* Y Hylidae Pseudocris maculata Boreal chorus frog N Hydrocharitaceae Egeria densa Brazilian elodea N Salmonidae Salvelinus fontinalis Brook trout* Y Colubridae Boiga irregularis Brown tree snake* -

Quantitative PCR Assays for Detecting Loach Minnow (Rhinichthys Cobitis) and Spikedace (Meda Fulgida) in the Southwestern United States

RESEARCH ARTICLE Quantitative PCR Assays for Detecting Loach Minnow (Rhinichthys cobitis) and Spikedace (Meda fulgida) in the Southwestern United States Joseph C. Dysthe1*, Kellie J. Carim1, Yvette M. Paroz2, Kevin S. McKelvey1, Michael K. Young1, Michael K. Schwartz1 1 United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, National Genomics Center for Wildlife and Fish Conservation, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Missoula, MT, United States of America, 2 United States a11111 Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southwestern Region, Albuquerque, NM, United States of America * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Loach minnow (Rhinichthys cobitis) and spikedace (Meda fulgida) are legally protected Citation: Dysthe JC, Carim KJ, Paroz YM, McKelvey with the status of Endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and are endemic to KS, Young MK, Schwartz MK (2016) Quantitative the Gila River basin of Arizona and New Mexico. Efficient and sensitive methods for moni- PCR Assays for Detecting Loach Minnow ’ (Rhinichthys cobitis) and Spikedace (Meda fulgida)in toring these species distributions are critical for prioritizing conservation efforts. We devel- the Southwestern United States. PLoS ONE 11(9): oped quantitative PCR assays for detecting loach minnow and spikedace DNA in e0162200. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162200 environmental samples. Each assay reliably detected low concentrations of target DNA Editor: Michael Hofreiter, University of York, UNITED without detection of non-target species, including other cyprinid fishes with which they co- KINGDOM occur. Received: April 27, 2016 Accepted: August 18, 2016 Published: September 1, 2016 Copyright: This is an open access article, free of all Introduction copyright, and may be freely reproduced, distributed, transmitted, modified, built upon, or otherwise used Loach minnow (Rhinichthys cobitis) and spikedace (Meda fulgida) are cyprinid fishes that were by anyone for any lawful purpose. -

Coronado National Forest Draft Land and Resource Management Plan I Contents

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Coronado National Forest Southwestern Region Draft Land and Resource MB-R3-05-7 October 2013 Management Plan Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona, and Hidalgo County, New Mexico The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Front cover photos (clockwise from upper left): Meadow Valley in the Huachuca Ecosystem Management Area; saguaros in the Galiuro Mountains; deer herd; aspen on Mt. Lemmon; Riggs Lake; Dragoon Mountains; Santa Rita Mountains “sky island”; San Rafael grasslands; historic building in Cave Creek Canyon; golden columbine flowers; and camping at Rose Canyon Campground. Printed on recycled paper • October 2013 Draft Land and Resource Management Plan Coronado National Forest Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona Hidalgo County, New Mexico Responsible Official: Regional Forester Southwestern Region 333 Broadway Boulevard, SE Albuquerque, NM 87102 (505) 842-3292 For Information Contact: Forest Planner Coronado National Forest 300 West Congress, FB 42 Tucson, AZ 85701 (520) 388-8300 TTY 711 [email protected] Contents Chapter 1. -

United States Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife

United States Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2321 West Royal Palm Road, Suite 103 Phoenix, Arizona 85021 Telephone: (602) 242-0210 FAX: (602) 242-2513 AESO/SE 02-21-00-F-0029 October 23, 2003 Memorandum To: Field Manager, Tucson Field Office, Bureau of Land Management, Tucson, Arizona From: Field Supervisor Subject: Biological Opinion: Livestock Grazing on 18 Allotments Along the Middle Gila River Ecosystem This biological opinion responds to your request for consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) pursuant to section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (16 U.S. C. 1531- 1544), as amended (ESA). Your original request was dated November 24, 2000, and received in our office November 27, 2000. Due to changes made in the proposed action, your office resubmitted the biological evaluation on March 12, 2001. Thus, formal consultation commenced on that date. At issue are impacts that may result from the Tucson Field Office’s grazing program in portions of the Middle Gila River Ecosystem, Gila and Pinal counties, Arizona. These impacts may affect the following listed species: southwestern willow flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus); cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl (Glaucidium brasilianum cactorum); lesser long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris curasoae yerbabuenae); spikedace (Meda fulgida); and loach minnow (Tiaroga cobitis), and critical habitat designated for the spikedace and loach minnow. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) requested our concurrence that the proposed action may affect, but is not likely to adversely affect, the Arizona hedgehog cactus (Echinocereus triglochidiatus var. arizonicus) and the bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). We concur with the BLM’s determinations for these species. -

Galiuro Mountains Unit, Graham County, Arizona MLA 21

I MI~A~J~L M)P~SAL OF CORONADO I NATIONAL FOREST, PART 9 I Galiuro Mountains Unit I Graham County, Arizona I Galiuro Muni~Untains I i A IZON I,' ' I BUREAU OF MINES UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR f United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF MINES INTERMOUNTAIN FIELD OPERATIONS CENTER "m II P.O. BOX 25086 II BUILDING 20, DENVER FEDERAL CENTER DENVER, COLORADO 80225 November 22, 1993 Nyal Niemuth Arizona Department of Mines and Mineral Resources 1502 West Washington Phoenix, AZ 85007 Dear Mr. Niemuth: Enclosed are two copies of the following U.S. Bureau of Mines Open File Report for your use: MLA 21-93 Mineral Appraisal of the Coronado National Forest, Part 9, Galiuro Mountains Unit, Graham County, Arizona If you would like additional copies, please notify Mark Chatman at 303-236-3400. Resource Evaluation Branch I i I MINERAL APPRAISAL OF THE CORONADO NATIONAL FOREST PART 9, GALIURO MOUNTAINS UNIT, I GRAHAM COUNTY, ARIZONA I I by. I S. Don Brown I MLA 21-93 I 1993 I I, i Intermountain Field Operations Center I Denver, Colorado I UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary BUREAU OF MINES I HERMANN ENZER, Acting Director I I I PREFACE I A January 1987 Interagency Agreement between the U.S. Bureau of Mines, U.S. Geological Survey, and U.S. Forest Service describes the purpose, authority, and I program operation for the forest-wide studies. The program is intended to assist the I Forest Service in incorporating mineral resource data in forest plans as specified by the National Forest Management Act (1976) and Title 36, Chapter 2, Part 219, Code of i Federal Regulations, and to augment the Bureau's mineral resource data base so that it can analyze and make available minerals information as required by the National I Materials and Minerals Policy, Research and Development Act (1980). -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES Tables STEPHEN T. ROSS University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 978-0-520-24945-5 uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 1 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 2 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 1.1 Families Composing 95% of North American Freshwater Fish Species Ranked by the Number of Native Species Number Cumulative Family of species percent Cyprinidae 297 28 Percidae 186 45 Catostomidae 71 51 Poeciliidae 69 58 Ictaluridae 46 62 Goodeidae 45 66 Atherinopsidae 39 70 Salmonidae 38 74 Cyprinodontidae 35 77 Fundulidae 34 80 Centrarchidae 31 83 Cottidae 30 86 Petromyzontidae 21 88 Cichlidae 16 89 Clupeidae 10 90 Eleotridae 10 91 Acipenseridae 8 92 Osmeridae 6 92 Elassomatidae 6 93 Gobiidae 6 93 Amblyopsidae 6 94 Pimelodidae 6 94 Gasterosteidae 5 95 source: Compiled primarily from Mayden (1992), Nelson et al. (2004), and Miller and Norris (2005). uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 3 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 3.1 Biogeographic Relationships of Species from a Sample of Fishes from the Ouachita River, Arkansas, at the Confl uence with the Little Missouri River (Ross, pers. observ.) Origin/ Pre- Pleistocene Taxa distribution Source Highland Stoneroller, Campostoma spadiceum 2 Mayden 1987a; Blum et al. 2008; Cashner et al. 2010 Blacktail Shiner, Cyprinella venusta 3 Mayden 1987a Steelcolor Shiner, Cyprinella whipplei 1 Mayden 1987a Redfi n Shiner, Lythrurus umbratilis 4 Mayden 1987a Bigeye Shiner, Notropis boops 1 Wiley and Mayden 1985; Mayden 1987a Bullhead Minnow, Pimephales vigilax 4 Mayden 1987a Mountain Madtom, Noturus eleutherus 2a Mayden 1985, 1987a Creole Darter, Etheostoma collettei 2a Mayden 1985 Orangebelly Darter, Etheostoma radiosum 2a Page 1983; Mayden 1985, 1987a Speckled Darter, Etheostoma stigmaeum 3 Page 1983; Simon 1997 Redspot Darter, Etheostoma artesiae 3 Mayden 1985; Piller et al. -

Aravaipa Canyon Ecosystem Management Plan

BLM Aravaipa Ecosystem Management Plan Final Aravaipa and Environmental Assessment Ecosystem Management Plan and Environmental Assessment Arizona • Gila District • Safford Field Office Field • Safford •District Gila Arizona September 2015 i April 2015 Mission Statements Bureau of Land Management The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is responsible for managing the National System of Public Lands and its resources in a combination of ways, which best serves the needs of the American people. The BLM balances recreational, commercial, scientific and cultural interests and it strives for long-term protection of renewable and nonrenewable resources, including range, timber, minerals, recreation, watershed, fish and wildlife, wilderness and natural, scenic, scientific and cultural values. It is the mission of the BLM to sustain the health, diversity and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. Arizona Game and Fish Department The mission of the Arizona Game and Fish Department is to conserve Arizona’s diverse wildlife resources and manage for safe, compatible outdoor recreation opportunities for current and future generations. The Nature Conservancy The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to preserve the plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. Cover photo: Aravaipa Creek. Photo © Greg Gamble/TNC BLM/AZ/PL-08/006 ii United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Safford Field Office 711 South 14th Avenue, Suite A Safford, Arizona 8 5546~3335 www.blm.gov/azl September 15, 2015 In Reply Refer To: 8372 (0010) Dear Reader: The document accompanying this letter contains the Final Aravaipa Ecosystem Management Plan, Environmental Assessment, Finding ofNo Significant Impact, and Decision Record. -

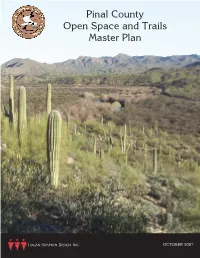

Final Open Space and Trails Master Plan

Pinal County Open Space and Trails Master Plan OCTOBER 2007 PINAL COUNTY Open Space and Trails Master Plan Board of Supervisors Lionel D. Ruiz, District 1, Chairman Sandie Smith, District 2 David Snider, District 3 Planning and Zoning Commission Kate Kenyon, Chairman Ray Harlan, Vice Chairman Commissioner Dixon Faucette Commissioner Frank Salas Commissioner George Johnston Commissioner Pat Dugan Commissioner Phillip “McD” Hartman Commissioner Scott Riggins Commissioner Mary Aguirre-Vogler County Staff Terry Doolittle, County Manager Ken Buchanan, Assistant County Manager, Development Services Manny Gonzalez, Assistant County Manager, Administrative Services David Kuhl, Director, Department of Planning and Development Terry Haifley, Director, Parks, Recreation & Fairgrounds Jerry Stabley, Deputy Director, Department of Planning and Development Kent Taylor, Senior Planner, Project Manager Prepared by: Approved October 31, 2007 Pinal County Open Space and Trails Master Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Project Overview..........................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background and Purpose .......................................................................................................................1 1.2 Planning Process Overview ....................................................................................................................1 2.0 Inventory and Analysis................................................................................................................................3 -

Sw - an Area Command Center Has Been Established for the Dude Fire

FIRE MANAGEMENT SITUATION REPORT SUNDAY 07/01/90 0900 HRS. MDT. PREPAREDNESS LEVEL III HIGHLIGHTS: SW - AN AREA COMMAND CENTER HAS BEEN ESTABLISHED FOR THE DUDE FIRE. DICK COX IS THE AREA COMMANDER. DUDE, TONTO N.F. - 28,480 ACRES. TYPE I TEAM (SHAW) COMMITTED TO THE WEST SIDE, TYPE I TEAM (MUECHEL) COMMITTED TO THE EAST SIDE AND TYPE I TEAM (GALLEGOS) COMMITTED TO THE APACHE-SITGREAVES. GOOD PROGRESS WAS ACCOMPLISHED IN ALL ZONES. MOP-UP STARTED IN ALL ZONES, WITH MAJOR EFFORT IN AND AROUND SUB DIVISIONS THAT WERE BURNED OVER, AND THE NORTHWEST CORNER OF ZONE 1. FIRE IS 95% CONTAINED WITH FULL CONTAINMENT EXPECTED TODAY, 7/1. FRIJOLE, GUADALUPE N.P. - 6,014 ACRES. TYPE I TEAM (DENTON) COMMITTED. FIRE WAS SLOWED BY A COMBINATION OF AIRTANKERS, HELICOPTERS BUCKET WORK AND HAND CREWS. ALL BUT THE NORTH SIDE OF THE FIRE IS FULLY CONTAINED. MOP-UP CONTINUES ON THE FLANKS. SOME RELEASES OF TYPE I CREWS AND OVERHEAD HAS BEGUN. CONTAINMENT EXPECTED TODAY, 7/1. COMMISSARY, SANTA FE N.F. - 235 ACRES. TYPE II TEAM (LENTE) COMMITTED. CONTAINED. MONTOSA, ARIZONA STATE - 10,000 ACRES. TYPE II TEAM (SHIVE) COMMITTED. ERRATIC WINDS, THUNDERSTORMS AND SPOT FIRES CONTINUE TO CAUSE CONTROL PROBLEMS. CONTAINMENT EXPECTED TODAY, 7/1. MAVERICK, CORONADO N.F. - 800 ACRES. FIRE IS BURNING IN THE GALIURO WILDERNESS IN GRASS/OAK BRUSH FUELS. THE CONTROL STRATEGY IS TO USE NATURAL BARRIERS AND TO BURN OUT IF THE FIRE MOVES TO PREDETERMINED LOCATIONS. CONTAINMENT EXPECTED 7/10. APACHE, CIBOLA N.F. - 250 ACRES. HISTORICAL CABIN WITHIN A MILE OF THE FIRE IS THREATENED. -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office 2321 West Royal Palm Road, Suite 103 Phoenix, Arizona 85021-4951 Telephone:(602) 242-0210 Fax: (602) 242-2513 In reply refer to: AESO/SE 02EAAZ00-2013-F-0363 May 13, 2015 Mr. Tom Osen, Forest Supervisor Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests . Post Office Box 640 Springerville, Arizona 85938-0640 Dear Mr. Osen: Thank you for your May 29, 2014 letter and Biological Assessment (BA), received on that same day, requesting initiation of formal consultation under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 153·1 et seq.) (ESA). At issue are impacts that may result from the revised programmatic "Land Management Plan for the Apache Sitgreaves National Forests" (LMP) for lands located in Apache, Navajo, and Greenlee Counties, Arizona (dated January 2013). The proposed action may affect the endangered New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus), the threatened Mexican spotted owl (Strix occidentalis lucida) and its critical habitat, the endangered southwestern willow flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) and its critical habitat, the threatened yellow-billed cuckoo (Coccyzils americanus occidentalis), the threatened northern Mexican gartersnake ( Thamnophis eques mega/ops), the threatened narrow• headed gartersnake ( Thamnophis rufipunctatus), the threatened Chiricahua leopard frog (Lithobates chiricahuensis) and its critical habitat, the endangered Three Forks springsnail (Pyrgulopsis trivialis) and its critical habitat, the threatened Apache trout (Oncorhynchus gilae apache), the endangered Gila chub (Gila intermedia) and its critical habitat, the threatened Gila . trout ( Oncorhynchus gilae gilae), the endangered spikedace (Meda fulgida ) and its critical habitat, the endangered loach minnow (Tiaroga cobitis) and its critical habitat, and the threatened Little Colorado spinedace (Lepidomeda vittata) and its critical habitat.