Chapter 1: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GS Misc 1158 GENERAL SYNOD 1 Next Steps on Human Sexuality Following the February 2017 Group of Sessions, the Archbishops Of

GS Misc 1158 GENERAL SYNOD Next Steps on Human Sexuality Following the February 2017 Group of Sessions, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York issued a letter on 16th February outlining their proposals for continuing to address, as a church, questions concerning human sexuality. The Archbishops committed themselves and the House of Bishops to two new strands of work: the creation of a Pastoral Advisory Group and the development of a substantial Teaching Document on the subject. This paper outlines progress toward the realisation of these two goals. Introduction 1. Members of the General Synod will come back to the subject of human sexuality with very clear memories of the debate and vote on the paper from the House of Bishops (GS 2055) at the February 2017 group of sessions. 2. Responses to GS 2055 before and during the Synod debate in February underlined the point that the ‘subject’ of human sexuality can never simply be an ‘object’ of consideration for us, because it is about us, all of us, as persons whose being is in relationship. Yes, there are critical theological issues here that need to be addressed with intellectual rigour and a passion for God’s truth, with a recognition that in addressing them we will touch on deeply held beliefs that it can be painful to call into question. It must also be kept constantly in mind, however, that whatever we say here relates directly to fellow human beings, to their experiences and their sense of identity, to their lives and to the loves that shape and sustain them. -

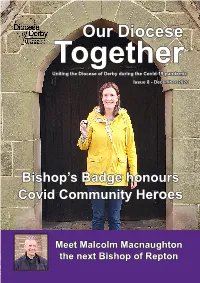

Together Uniting the Diocese of Derby During the Covid-19 Pandemic Issue 8 - December 2020

Our Diocese Together Uniting the Diocese of Derby during the Covid-19 pandemic Issue 8 - December 2020 Bishop’s Badge honours Covid Community Heroes Meet Malcolm Macnaughton the next Bishop of Repton News Advent Hope Between 30 November and 24 December 2020, Bishop Libby invites you to join her each week for an hour of prayer and reflection based upon seasonal Bible passages and collects as together we look for the coming of Christ and the hope that gives us of his kingdom. Advent Hope is open to all and will be held on Mondays from 8am - 9am and repeated on Thursdays from 8pm - 9pm. Email [email protected] for the access link. Interim Diocesan Director of Education announced Canon Linda Wainscot, formerly Director of Education for the Diocese of Coventry, will take up the position as Interim Diocesan Director of Education for two days a week during the spring term 2021. Also, Dr Alison Brown will continue to support headteachers and schools, offering one and two days a week as required, ensuring their Christian Distinctiveness within the diocese. Both roles will be on a consultancy basis, starting in January 2021. Linda said: “Having had a long career in education, I retired in August 2020 from my most recent role as Diocesan Director of Education (DDE) for the Diocese of Coventry (a post I held for almost 20 years). Prior to this, I was a teacher and senior leader in maintained and independent schools and an FE College as well as being involved in teacher training. In addition to worshipping in Rugby, I am privileged to be an Honorary Canon of Coventry Cathedral and for two years I was the chair of the Anglican Association of Directors of Education. -

Weekly Intercessions

Weekly Intercessions in the Scottish Episcopal Church in the Charges of St Margaret, Renfrew & St John, Johnstone Week beginning Sunday 26 April 2020 For use at home during the COVID-19 social distancing and isolation from corporate worship The aim of this leaflet is to help you pray at home as part of the Worldwide Anglican family in the Scottish Episcopal Church. Please use this sheet in conjunction with weekly Pewsheet and the SEC Daily Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer. You can follow these Daily Offices online at www.scotland.anglican.org/spirituality/prayer/daily-offices/ where you will find Morning Prayer, Evening Prayer and Night Prayer each day of the week. All the Psalm and Bible texts are automatically there for the day and any commemoration or Festival. Just before the Lord’s Prayer you can insert these prayer intentions for the day and the names of those for whom we have been asked to pray in their different needs from the Pewsheet. Stations of the Resurrection – Love Lives Again are now available on our website. 47mins to relax into the resurrection encounters of Jesus with the disciples. Dwell with the images, dwell with the bible readings and join in the prayers. www.SECStJohnStMargaret.org.uk NATIONAL DAY OF PRAYER each SUNDAY 7pm The Call to a National Day of Prayer, is in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, people of faith across our nation are invited to join in prayerful solidarity with this witness. Light a candle at 7pm each Sunday, in the window of our homes as a visible symbol of the light of life, Jesus Christ, the source of hope in this life. -

Faith in Derbyshire

FaithinDerbyshire Derby Diocesan Council for Social Responsibility Derby Church House Full Street Derby DE1 3DR Telephone: 01332 388684 email: [email protected] fax: 01332 292969 www.derby.anglican.org Working towards a better Derbyshire; faith based contribution FOREWORD I am delighted to be among those acknowledging the significance of this report. Generally speaking, people of faith are not inclined to blow their own trumpets. This report in its calm and methodical way, simply shows the significant work quietly going on through the buildings and individuals making up our faith communities. Such service to the community is offered out of personal commitment. At the same time, it also deserves acknowledgment and support from those in a position to allocate resources, because grants to faith communities are a reliable and cost effective way of delivering practical help to those who need it. Partnership gets results. This report shows what people of faith are offering. With more partners, more can be offered. David Hawtin Bishop of Repton and Convenor of the Derbyshire Church and Society Forum I am especially pleased that every effort has been taken to make this research fully ecumenical in nature, investigating the work done by churches of so many different denominations: this makes these results of even greater significance to all concerned. I hope that a consequence of churches collaborating in this effort will be an increased partnership across the denominations in the future. Throughout their history Churches have been involved in their communities and this continues today. In the future this involvement is likely to result in increasing partnerships, not only with each other but also with other agencies and community groups. -

Cycle of Prayer Those I Live With, Those I Rub Shoulders With, Those I Work With, Those I Don’T Get on With, Thursday 29 May Each Be the Focus of My Prayer

September 2016 Wednesday 28 Friday 30 Pray for all preparing for the new term at This world I live in, this town I live in, University, especially those leaving home for this street I live in, this house I live in, the first time may each be the focus of my prayer. Cycle of Prayer Those I live with, those I rub shoulders with, those I work with, those I don’t get on with, Thursday 29 may each be the focus of my prayer. Michael and All Angels Those who laugh, those who cry, those who Thursday 1 Monday 5 hurt, those who hide, Pray that the Church as a body will be em- In the United Benefice of Morton and Stone- For a first day at school powered to stand up against powers of dark- may each be the focus of my prayer. broom with Shirland the parish of Holy Cross, Prayers centred less on self and more on ness and bring God’s light into the world. Morton, during the vacancy of Vicar, do pray O God, the strength of my life, let me be others, for those who have responsibility for the care less on my circumstances, more on the needs strong today as I meet new people in new If we had a fraction of the faith in you that you of this parish and those who will support the places. have in us of others. Churchwardens and PCC Clergy: May my life be likewise centred less on self help me to discover friends among strangers, then this world would be transformed, Lord. -

Newsletter Sunday 9Th February 2020

Newsletter Sunday 9th February 2020 Sun 9th 8.00am - BCP Communion (Church) 9.00am - Parish Communion (Church) 10.45am - Morning Praise with Communion (Church) 4.00pm - Asian Congregation (Centre) 6.30pm - Church Hill Praise (Church) Mon 10th 9.00am - Play and Pray (Church) 3.15pm - Kids Club (Centre) 7.30pm - Personnel Committee (Rectory) 7.30pm - Whole Church Prayer: Imagine (Church) Tues 11th 10.00am - Open Church 3.15pm - Younger Youth (Centre) 7.30pm - Passage & Praise Rehearsal Wed 12th 9.30am - Toddlers (Centre) 4.00pm - Joint Christian Union (Crescent Baptist Church) 7.30pm - Bellringing Practice 7.30pm - The Bible Course (Church Centre) 7.30pm - Band Rehearsal (Church) Thurs 13th 2.00pm - OWLs (Centre) 4.30pm - Blue Coat Academy Governors Fri 14th Church Office Closed 8.40am - Blue Coat Academy Assembly (Church) 9.30am - Church Open, Cleaning and Flower Arrangers (Church) 7.30pm - Signs for Worship Walsall (Centre) Sat 15th Sun 16th 8.00am - BCP Communion (Church) 9.00am - Parish Communion (Church) 10.45am - Morning Praise (Church) 4.00pm - Asian Congregation (Centre) 6.30pm - Church Hill Praise (Church) Further ahead Mon 17th 7.30pm - Whole Church Prayer: Imagine (Church) Thurs 20th 7.30pm - Deanery Synod standing committee Mon 24th 9.00am - Staff Team meeting 7.30pm - Whole Church Prayer: Imagine (Church) Over half-term week 17th-21st February the Church Centre will be closed, and we will be operating on a skeleton staff. Worshipping God; Equipping his people; Growing his kingdom; Serving Walsall Prayer Requests From Church Rotas Mike Ray has kindly agreed to to Lichfield with her husband Andrew and take our prayer cards and email look after the Church rotas till April to allow on her new role in April, after almost four years prayers. -

Deanery News November 2020

Deanery News November 2020 Hope – the universal currency 2021 Dairy Dates: Deanery Synod Meetings With recent announcements from Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna and a fur- ther encouraging announcement this week from the Oxford- AstraZeneca 7pm via Zoom team, we are witnessing remarkable scientific advances coupled with in- creasing confidence that COVID can be controlled. Deputy Chief Medical Extraordinary meeting: th Officer Professor Jonathan Van-Tam likened it to a penalty shoot out with Wednesday 27 January Pfizer’s results the first goal in the back of the net, Moderna’s the second. (Vision consultation) As each goal is scored, confidence grows and with it hope. Wednesday April 21st The sense of optimism that we might have turned a significant corner is st countered by reflections on lives lost, the thoughts and worries that trou- Wednesday July 21 ble us, the isolation and loneliness we still feel, and now placed in tier 3 Wednesday October 20th restrictions. Yet hope knows no boundaries. It is the universal currency of all humanity. Just as the sun breaks through each morning, so hope breaks Leadership Team through at every opportunity. Meetings As we ponder on the immediate horizon of 'what will Christmas be like?’ Wednesday 20th January the horizon beyond may elude us. 2021 will be a pivotal year. Whilst much of our national life will hope to be gathered around the mass vaccination Tuesday 23rd March of millions, much of our diocesan life will gather around the vision and Tuesday 6th July strategic priorities emerging from it. This may seem inconsequential com- pared with the urgent national scene, but it will occupy significant space in Tuesday 28th September our common life as church within community. -

The Diocesan Cycle of Prayer Is the Means Whereby All the People of the Diocese, and of the Church in Scotland and Further Afield, Can Be Covered by Prayer Each Month

The Diocesan Cycle of Prayer is the means whereby all the people of the Diocese, and of the Church in Scotland and further afield, can be covered by prayer each month. The Cycle is observed by churches in the Diocese, but please also consider making it a cornerstone of your own daily devotions. We acknowledge our enormous debt of gratitude and love that go out in our prayers for our sister Diocese of Argyll and The Isles and its people. We will continue praying for them during their episcopal vacancy. You may wish to refer to the Anglican Cycle of Prayer. https://www.anglicancommunion.org/resources/cycle-of-prayer.aspx You can also use the Porvoo Prayer Diary 2020. https://glasgow.anglican.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/PORVOO-PRAYER-DIARY-2020.pdf This version is current as of 15th July 2020, for an updated version, please, refer to the Diocesan Cycle of Prayer online. https://glasgow.anglican.org/resources/diocesan-cycle-of-prayer/ • Bishop Kevin Pearson, Bishop of the United Diocese of Glasgow and Galloway; Bishop Mark Strange, Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church; the people of Scotland. • Scottish Episcopal Church: Those in training for ordained and lay ministries. • Bishop Gregor Duncan, Bishop Idris Jones, Bishop John Taylor, Bishop Gordon Mursell, all retired clergy and those in Post-Retiral Ministry. • The Church of Scotland. • The Roman Catholic Church in Scotland. • Bishop Kevin Pearson, Bishop of the United Diocese of Glasgow and Galloway; Bishop Mark Strange, Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church; the people of Scotland. • Porvoo Link: The Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church. -

Cyprianlife July Aug 09

Cyprian Ordination in St Cyprian’s 5th July at 6pm The Magazine of St Cyprian’s Church, Lenzie July & August 2009 1 Scottish Episcopal Church Vestry Rector@ (Chairman) Diocese of Glasgow & Galloway Lay Representative@ Barbara Parfitt st 11A Kirkintilloch Road, Lenzie G66 4RW. Bishop (retires 31 July 2009): ) 776 0543 The Most Revd. Dr. Idris Jones Secretary@ Sally Pitches, Inchwood Cot- Bishop’s Office, Diocesan Centre tage, Kilsyth Road, Milton of Campsie, 5 St Vincent Pl., Glasgow G1 2DH ) ) G66 8AL 01236 823880 0141-221 6911 fax 0141-221 6490 Treasurer@ Maxine Gow,12 Alder Road, email: [email protected] Milton of Campsie G66 8HH ) 01360 310420 Property Convenor Adrian Clark, Solsgirth Lodge, Langmuir Road, Kirkintilloch G66 ) 776 2160 Cyprian Elected Members Gavin Boyd, Avril Critchlow, Catherine Gunnee, Paul Hindle, Sandy Jamieson, Eric Parry, Vivienne Prov- an, Kevin Wilbraham. Contacts 3C Group@ Susan Frost 776 4135 The News Magazine of Altar Guild@ Anne Carswell 776 3354 St. Cyprian’s Church, Altar Servers Eric Parry 776 4991 Beech Road, Lenzie, Glasgow. G66 4HN Alt. Lay Rep@ Glennis Tavener 775 2895 Scottish Charity No. SC003826 Bible Rdg Fellowship Prim Parry 776 4991 The Scottish Episcopal Church is in full Car Pool Eric Parry 776 4991 communion with the Church of England and Fair Trade@ Vivienne Provan 776 6422 all other churches of the Anglican Gift Aid@ Aileen Mundy 578 9449 Communion throughout the world Hall Bookings@ Gavin Boyd 776 2812 Link@ Kathryn Potts 578 0734 Magazine@ Paul Hindle 776 3237 Rector fax 578 3706 MU@ Catherine Gunnee 578 1937 The Revd. -

Mission and Ministry’

Durham E-Theses The Leadership Role of the Bishop and his Sta Team in the Formation of Strategy for Missional Ministry JONES, TREVOR,PRYCE How to cite: JONES, TREVOR,PRYCE (2013) The Leadership Role of the Bishop and his Sta Team in the Formation of Strategy for Missional Ministry, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8479/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Leadership Role of the Bishop and his Staff Team in the Formation of Strategy for Missional Ministry A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Theology and Ministry in Durham University Department of Theology and Religion by The Venerable Trevor Pryce Jones 2013 Abstract Dioceses of the Church of England are engaged in the process of forming strategies for missional ministry. -

February 2006 the Magazine of the Parish of Pentyrch with Capel Llanilltern

February 2006 The Magazine of The Parish of Pentyrch with Capel Llanilltern St Catwg’s Church, Pentyrch St David’s Church, Groesfaen St Ellteyrn’s Church, Capel Llanilltern For 2006 the price of the magazine will remain at £5.00 for an annual subscription, and 60 pence for individual copies. Price 60 pence Subscriptions are now due. THE PARISH OF PENTYRCH VICAR The Rev. John Binny, The Vicarage, Pentyrch. Tel: 029 20890318 SUNDAY SERVICES St. Catwg’s Church, Pentyrch 8.00 a.m. Holy Eucharist (4th Sunday only) 9.00 a.m. Parish Eucharist (Except the first Sunday in the month) 6.00 p.m. Evensong (Holy Eucharist on 1st Sunday in the month) St. David’s Church Groesfaen 8.00 a.m. Holy Eucharist (1st Sunday only) 10.30 a.m. Sung Eucharist (Except the first Sunday in the month) St Ellteyrn’s Church Capel Llanilltern 10.30 a.m. Holy Eucharist Parish Hall Creigiau 10.30 a.m. First Sunday in every month Parish Family Communion WEEKDAYS St. Catwg’s Holy Eucharist Wednesday 10.00 a.m. St. David’s Holy Eucharist Tuesday 10.00 a.m. Other services as announced SUNDAY SCHOOL St. Catwg’s 10.30 am every Sunday in Church (except the first Sunday in the month) BAPTISM, HOLY MATRIMONY, BANNS OF MARRIAGE Articles for the magazine can be E-mailed to: [email protected] by the 10th of the month. 2 From the Vicarage Window DEAR FRIENDS tion gone, and when they meet so –and- so in his or her usual, irritating mood, I wonder how many of you made New they say what they think – and there is Year Resolutions at the beginning of another resolution gone. -

Issue 45 NOVEMBER 2012

The Trades House of Glasgow issue 45 NOVEMBER 2012 FOUR CENTURIES HONOURED Full Story Page 2 IN THIS ISSUE View from the Platform Clean Sweep for BAE Apprentices Combat Stress – Charity of the Year Chain Gang Visits Kelvindale Primary Takes Citizenship Title Glasgow Ball Glasgow Trades Return to Maryhill Coat Creator Wins Craftex Craft News House Dinners Highland Lamp Voted Tops Sports Desk The Craftsman THE DRAPERS’ FUND FOUR CENTURIES I was deeply honoured to receive the position as Drapers’ Manager last November. Like many in the House I was aware of the fund which James Inglis set up in 1918 but had not realised just how our society HONOURED is failing to assist those less fortunate than ourselves within our own City of Glasgow. The Rt Rev Dr Idris Jones (left) with Col John L Kelly. Honouring four centuries of tradition, an historic ceremony at the Trades Hall The Drapers’ Fund Manager Hamilton Purdie and his Committee accept a £20,000 heralded the election of Colonel John Lewis Kelly MBE BSc FRGS as Deacon cheque from Maureen Holmes Henderson. Convener of the Trades of Glasgow and the Right Reverend Dr Idris Jones as I am assisted by a committee of three - Alison Dick, Scott Waugh and Collector. They will lead the organisation until October 2013. Ford McFarlane, together with Myra Ramsay and her Trades House John, who also assumes the role of Third Citizen of Glasgow for one year, retired in staff who provide secretarial support. We meet every few weeks and 2011 as a senior army officer following an extensive military career that took him receive over 300 requests for assistance throughout the year, generally across the world.