The Nature of the Radio-Quiet Compact X-Ray Source in SNR RCW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Type of Black Hole Detected in Massive Collision That Sent Gravitational Waves with a 'Bang'

New type of black hole detected in massive collision that sent gravitational waves with a 'bang' By Ashley Strickland, CNN Updated 1200 GMT (2000 HKT) September 2, 2020 <img alt="Galaxy NGC 4485 collided with its larger galactic neighbor NGC 4490 millions of years ago, leading to the creation of new stars seen in the right side of the image." class="media__image" src="//cdn.cnn.com/cnnnext/dam/assets/190516104725-ngc-4485-nasa-super-169.jpg"> Photos: Wonders of the universe Galaxy NGC 4485 collided with its larger galactic neighbor NGC 4490 millions of years ago, leading to the creation of new stars seen in the right side of the image. Hide Caption 98 of 195 <img alt="Astronomers developed a mosaic of the distant universe, called the Hubble Legacy Field, that documents 16 years of observations from the Hubble Space Telescope. The image contains 200,000 galaxies that stretch back through 13.3 billion years of time to just 500 million years after the Big Bang. " class="media__image" src="//cdn.cnn.com/cnnnext/dam/assets/190502151952-0502-wonders-of-the-universe-super-169.jpg"> Photos: Wonders of the universe Astronomers developed a mosaic of the distant universe, called the Hubble Legacy Field, that documents 16 years of observations from the Hubble Space Telescope. The image contains 200,000 galaxies that stretch back through 13.3 billion years of time to just 500 million years after the Big Bang. Hide Caption 99 of 195 <img alt="A ground-based telescope&amp;#39;s view of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a neighboring galaxy of our Milky Way. -

407 a Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , 351–353 Achromat

Index A Barnard 72 , 210–211 Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , Barnard, E.E. , 5, 389 351–353 Barnard’s loop , 5–8 Achromat , 365 Barred-ring spiral galaxy , 235 Adaptive optics (AO) , 377, 378 Barred spiral galaxy , 146, 263, 295, 345, 354 AGC S 373. See Abell Galaxy Cluster Bean Nebulae , 303–305 S 373 (AGC S 373) Bernes 145 , 132, 138, 139 Alnitak , 11 Bernes 157 , 224–226 Alpha Centauri , 129, 151 Beta Centauri , 134, 156 Angular diameter , 364 Beta Chamaeleontis , 269, 275 Antares , 129, 169, 195, 230 Beta Crucis , 137 Anteater Nebula , 184, 222–226 Beta Orionis , 18 Antennae galaxies , 114–115 Bias frames , 393, 398 Antlia , 104, 108, 116 Binning , 391, 392, 398, 404 Apochromat , 365 Black Arrow Cluster , 73, 93, 94 Apus , 240, 248 Blue Straggler Cluster , 169, 170 Aquarius , 339, 342 Bok, B. , 151 Ara , 163, 169, 181, 230 Bok Globules , 98, 216, 269 Arcminutes (arcmins) , 288, 383, 384 Box Nebula , 132, 147, 149 Arcseconds (arcsecs) , 364, 370, 371, 397 Bug Nebula , 184, 190, 192 Arditti, D. , 382 Butterfl y Cluster , 184, 204–205 Arp 245 , 105–106 Bypass (VSNR) , 34, 38, 42–44 AstroArt , 396, 406 Autoguider , 370, 371, 376, 377, 388, 389, 396 Autoguiding , 370, 376–378, 380, 388, 389 C Caldwell Catalogue , 241 Calibration frames , 392–394, 396, B 398–399 B 257 , 198 Camera cool down , 386–387 Barnard 33 , 11–14 Campbell, C.T. , 151 Barnard 47 , 195–197 Canes Venatici , 357 Barnard 51 , 195–197 Canis Major , 4, 17, 21 S. Chadwick and I. Cooper, Imaging the Southern Sky: An Amateur Astronomer’s Guide, 407 Patrick Moore’s Practical -

Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy of Dusty Galactic Nuclei

RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy of Dusty Galactic Nuclei PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Wiskunde en Natuurwetenschappen aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 20 oktober 2003 om 11.00 uur door Henrik Willem Walter Spoon geboren op 1 maart 1968 te Woudenberg Promotor: Prof. dr. A. G. G. M. Tielens Beoordelingscommissie: Dr. P.D. Barthel Prof. dr. G. Miley Prof. dr. D.B. Sanders ISBN 90–367–1902–X Voor mijn ouders Cover: Morning twilight on the Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia on April 2, 1996. An ‘embedded’ power source illuminates the ring-like salt structures, which are reminiscent of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon molecules (PAHs). Overhead, the dusty southern starburst galaxy NGC 4945. Cover designed by Jack Waas. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 ULIRGs: the last of the Mohicans : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 1 1.2 Starburst in the Nearby Universe : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 2 1.3 Characteristics of regions of massive star formation in our own Galaxy : : : 5 1.3.1 Observable characteristics : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 5 1.4 AGNs : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 9 1.4.1 Observable characteristics : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 10 1.5 ULIRGs at mid-infrared wavelengths : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 10 1.6 In this thesis : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 12 2 Ice features in the -

Arxiv:Astro-Ph/0510630V1 20 Oct 2005 a Eateto Srnm,Uiest Fwsosn 7 .Ch N

Accepted for Publication in the Astronomical Journal on 10/18/2005 A Spitzer Space Telescope Infrared Survey of Supernova Remnants in the Inner Galaxy William T. Reach, Jeonghee Rho, Achim Tappe, Thomas G. Pannuti Spitzer Science Infrared Center, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 Crystal L. Brogan Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 640 N. A’ohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720 Edward B. Churchwell, Marilyn R. Meade, Brian Babler Department of Astronomy, University of Wisconsin, 475 N. Charter Street, Madison, WI 53706 R´emy Indebetouw Astronomy Department, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904 Barbara A. Whitney Space Science Institute, Boulder, CO 80303 [email protected] arXiv:astro-ph/0510630v1 20 Oct 2005 ABSTRACT Using Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) images at 3.6, 4.5, 5.8, and 8 µm from the GLIMPSE Legacy science program on the Spitzer Space Telescope, we searched for infrared counterparts to the 95 known supernova remnants that are located within galactic longitudes 65◦ > |l| > 10◦ and latitudes |b| < 1◦. Eighteen infrared counterparts were detected. Many other supernova remnants could have significant infrared emission but are in portions of the Milky Way too confused to allow separation from bright H II regions and pervasive mid-infrared emis- sion from atomic and molecular clouds along the line of sight. Infrared emission from supernova remnants originates from synchrotron emission, shock-heated dust, atomic fine-structure lines, and molecular lines. The detected remnants are –2– G11.2-0.3, Kes 69, G22.7-0.2, 3C 391, W 44, 3C 396, 3C 397, W 49B, G54.4-0.3, Kes 17, Kes 20A, RCW 103, G344.7-0.1, G346.6-0.2, CTB 37A, G348.5-0.0, and G349.7+0.2. -

ESO Annual Report 2018 Posals to ALMA Every Year

ESO European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere Annual Report 2018 ESO European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere Annual Report 2018 Presented to the Council by the Director General Xavier Barcons The European Southern Observatory ESO, the European Southern Observa tory, is the foremost intergovernmental astronomy organisation in Europe. It ESO/M. Claro has 16 Member States: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, along with the Host State of Chile, and with Australia as a Strategic Partner. Several other countries have expressed an interest in membership. Created in 1962, ESO carries out an ambi tious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful groundbased observing facilities, ena bling astronomers to make important scientific discoveries. ESO also plays a leading role in promoting and organising cooperation in astronomical research. ESO operates three worldclass observ The VLT at the Paranal Observatory at sunset. this interferometric mode, the telescope’s ing sites in the Atacama Desert region vision is as sharp as that of a telescope of Chile: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. The VLT is a unique facility and arguably as large as the separation between La Silla, located 2400 metres above sea the world’s most advanced optical instru the most distant mirrors. For the VLTI, level and 600 kilometres north of Santiago ment. It is not just one telescope but an this can be up to 200 metres. de Chile, was ESO’s first observatory. -

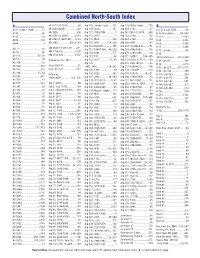

Combined North and South Atlas Index 64K PDF Download

Combined North-South Index A––––––––––––––– AB 2877 (IC 1633)...............S9 Arp 103, Zwicky Triplet ......173 Arp 248, Wild’s Triplet .......120 B––––––––––––––– A101, in M33, 0589.............17 AB 3389 (2235).................S42 Arp 104, 5216....................151 Arp 259, 1741......................47 B 3, B 4, Ldn 1470...............38 A104 ....................................48 AB 3526.............................S86 Arp 112, 7805/7806...............1 Arp 261, MCG-2-38-16......S98 B 33, Horsehead..........55, S40 A105 ....................................48 AB 3656 (IC 4931)...........S120 Arp 113, 0070........................2 Arp 263, 3239....................107 B 44A...............................S104 A205 ..................................104 AB 3828 (7180/7185)......S133 Arp 116, M60.....................143 Arp 264, 3104....................104 B 68.................................S106 A444 ......................................1 AB 3980...................250, S140 Arp 120, 4438 ...........134, S82 Arp 266, 4861....................147 B 69.................................S106 Arp 122, 6040A/B ..............168 Arp 268, Holmberg II...........91 B 71.................................S106 AB 71...................................S5 AM 0608-332/AB 3381......S41 Arp 123, 1888/1889 ....49, S38 Arp 269, 4485/4490...........136 B 72, Ldn 66......................178 AB 76...................................S6 AM 1724-622...................S107 Arp 124, 6361....................177 Arp 270, 3395/3396...........110 B 85, AB 119...........................10, -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism. -

Astronomy Raisbeck Aviation High School Invitational Science Olympiad Tournament December 2Nd, 2017 Instructions: • DO NOT OPEN THIS TEST UNTIL INSTRUCTED to DO SO

Team number: ________ Team Name: _______________________________ Score: ________ Rank: _____ Participant Names: ___________________________________________________________________________ Astronomy Raisbeck Aviation High School Invitational Science Olympiad Tournament December 2nd, 2017 Instructions: • DO NOT OPEN THIS TEST UNTIL INSTRUCTED TO DO SO. • You have 50 minutes to complete this event. • Write on the papers provided. • Questions are worth 1 point unless stated otherwise • You are allowed one of the following sources of information: two computers/tablets of any kind; one computer/tablet and one three-ring binder; or, two three-ring binders. • Your team may bring two calculators of any type dedicated to computation to use during the event. • No Internet access is allowed during any part of this event. • In the case of a tie it will be broken with the tie breaker (this does not count toward your score). Tie Breaker YOU MUST ANSWER THIS QUESTION: Tie Breakers: You MUST answer this question: How fast was the New Horizons spacecraft traveling at its closest approach to Pluto? State your answer in meters per second: Use the diagram below to answer the next FOUR questions. 1. This is a light curve for what type of 3. What is the absolute magnitude of this variable star? star? A. Cephied A. -24.0 B. Semiregular variable B. -18.7 C. Luminous blue variable C. -5.6 D. Wolf-Rayet star D. -4.1 E. Pulsar E. -2.3 F. Magnetar F. 17.5 G. Eclipsing binary G. 18.7 H. X-ray binary H. 20.0 I. Gamma-ray binary I. 24.0 J. Type II supernova J. -

Spectral Analysis of Bullet Fragments in RCW 103 1

Spectral Analysis of Bullet Fragments in RCW 103 Adrian Arteaga Harvard College Patrick Slane, Ph.D. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Abstract We conduct spectral analysis on what appear to be explosion fragments outside of the forward shock boundary of SNR RCW 103. We compare the metal abundances of these fragments to the metal abundances of regions of shocked ISM material near the edge of the remnant, in order to determine whether the fragments are supernova ejecta, or heated clouds of shocked ISM. We detect overabundances of Silicon in all three fragments, which suggests that the fragments are ejecta. 8 May 2013 1. Introduction Big Bang nucleosynthesis produced elements no heavier than Beryllium, and inside of stars, only elements up to iron are produced. The 64 remaining naturally occurring elements are fused in supernova explosions, and seeded throughout the galaxy via the interactions of the explosion’s remnant with the interstellar medium (ISM). From a biological perspective, supernova remnants (SNRs) are important because life as we know it is dependent on elements originally found only inside these remnants. By acting as light-year-wide mixing grounds, supernova remnants make the galaxy a chemically diverse place, and one in which life can flourish. Several other important galactic phenomena are the direct result of SNRs. Galactic cosmic rays, for example, are widely believed to originate in the shock fronts of supernova remnants. They themselves are of great scientific value because their incredibly high energies are orders of Printed by Mathematica for Students 2 SpectralAnalysisofExplotionFragmentsInRCW103.nb magnitude above those achieved by the most powerful man-made particle accelerators. -

332 — 15 August 2020 Editor: Bo Reipurth ([email protected]) List of Contents the Star Formation Newsletter Interview

THE STAR FORMATION NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to early stellar/planetary evolution and molecular clouds No. 332 — 15 August 2020 Editor: Bo Reipurth ([email protected]) List of Contents The Star Formation Newsletter Interview ...................................... 3 Abstracts of Newly Accepted Papers ........... 5 Editor: Bo Reipurth [email protected] Dissertation Abstracts ........................ 46 Associate Editor: Anna McLeod New Jobs ..................................... 50 [email protected] Meetings ..................................... 51 Technical Editor: Hsi-Wei Yen Summary of Upcoming Meetings .............. 52 [email protected] Editorial Board Joao Alves Alan Boss Cover Picture Jerome Bouvier Lee Hartmann The large bow shock HH 216 in M16 is seen here Thomas Henning in an HST image. The shock is driven by a source Paul Ho embedded at the tip of one of the many elephant Jes Jorgensen trunks in this region. Charles J. Lada Thijs Kouwenhoven Image courtesy STScI. Michael R. Meyer Ralph Pudritz Luis Felipe Rodríguez Ewine van Dishoeck Hans Zinnecker Submitting your abstracts The Star Formation Newsletter is a vehicle for fast distribution of information of interest for as- Latex macros for submitting abstracts tronomers working on star and planet formation and dissertation abstracts (by e-mail to and molecular clouds. You can submit material [email protected]) are appended to for the following sections: Abstracts of recently each Call for Abstracts. You can also accepted papers -

October 2018 BRAS Newsletter

Monthly Meeting Monday, October 8th at 7PM at HRPO (Monthly meetings are on 2nd Mondays, Highland Road Park Observatory). Presenter: Stephen Tilley on “Comet and Asteroid Observing Using Internet Telescopes” What's In This Issue? President’s Message Secretary's Summary Outreach Report Astrophotography Group Light Pollution Committee Report “Free The Milky Way” Campaign Recent Forum Entries Messages from the HRPO Friday Night Lecture Series Globe at Night 12th Annual Spooky Spectrum Natural Sky Conference Observing Notes – Norma – The Rule & Mythology Like this newsletter? See PAST ISSUES online back to 2009 Visit us on Facebook – Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Newsletter of the Baton Rouge Astronomical Society October 2018 © 2018 President’s Message We are now moving into fall and longer nights. As we move towards winter and the end of the year, we can look forward with "guarded" optimism to Comet 46P/Wirtanen. The University of Maryland's Comet Wirtanen Campaign webpage (http://wirtanen.astro.umd.edu/46P/4 6P_status.shtml ) reports visual observations of the comet are following Yoshida's prediction suggests that the comet "may" reach naked eye brightness in December. REMINDERS: We plan to have a picnic at LIGO on Science Saturday, November 17, 2018. I hope to see you there. The BRAS Business Meeting will be Wednesday October 3, HRPO at 7 PM. The BRAS Monthly Meeting will be Monday October 8, HRPO at 7 PM. I will give a talk on Comet and Asteroid Observing using internet telescopes. If you have not reserved your member pin yet, please come to a meeting to pick one up. -

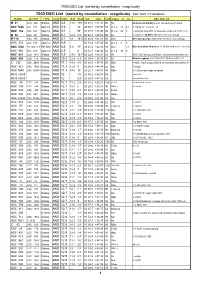

DSO List V2 Current

7000 DSO List (sorted by constellation - magnitude) 7000 DSO List (sorted by constellation - magnitude) - from SAC 7.7 database NAME OTHER TYPE CON MAG S.B. SIZE RA DEC U2K Class ns bs SAC NOTES M 31 NGC 224 Galaxy AND 3.4 13.5 189' 00 42.7 +41 16 60 Sb Andromeda Galaxy;Local Group;nearest spiral NGC 7686 OCL 251 Opn CL AND 5.6 - 15' 23 30.1 +49 08 88 IV 1 p 20 6.2 H VIII 69;12* mags 8...13 NGC 752 OCL 363 Opn CL AND 5.7 - 50' 01 57.7 +37 40 92 III 1 m 60 9 H VII 32;Best in RFT or binocs;Ir scattered cl 70* m 8... M 32 NGC 221 Galaxy AND 8.1 12.4 8.5' 00 42.7 +40 52 60 E2 Companion to M31; Member of Local Group M 110 NGC 205 Galaxy AND 8.1 14 19.5' 00 40.4 +41 41 60 SA0 M31 Companion;UGC 426; Member Local Group NGC 272 OCL 312 Opn CL AND 8.5 - 00 51.4 +35 49 90 IV 1 p 8 9 NGC 7662 PK 106-17.1 Pln Neb AND 8.6 5.6 17'' 23 25.9 +42 32 88 4(3) 14 Blue Snowball Nebula;H IV 18;Barnard-cent * variable? NGC 956 OCL 377 Opn CL AND 8.9 - 8' 02 32.5 +44 36 62 IV 1 p 30 9 NGC 891 UGC 1831 Galaxy AND 9.9 13.6 13.1' 02 22.6 +42 21 62 Sb NGC 1023 group;Lord Rosse drawing shows dark lane NGC 404 UGC 718 Galaxy AND 10.3 12.8 4.3' 01 09.4 +35 43 91 E0 Mirach's ghost H II 224;UGC 718;Beta AND sf 6' IC 239 UGC 2080 Galaxy AND 11.1 14.2 4.6' 02 36.5 +38 58 93 SBa In NGC 1023 group;vsBN in smooth bar;low surface br NGC 812 UGC 1598 Galaxy AND 11.2 12.8 3' 02 06.9 +44 34 62 Sbc Peculiar NGC 7640 UGC 12554 Galaxy AND 11.3 14.5 10' 23 22.1 +40 51 88 SBbc H II 600;nearly edge on spiral MCG +08-01-016 Galaxy AND 12 - 1.0' 23 59.2 +46 53 59 Face On MCG +08-01-018