CUERPO DIRECTIVO Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTA: Las Canciones Que Dicen (Pista) Es Porque Solo Esta El

NOTA: Las Canciones Que Dicen (Pista) Es Porque Solo Esta El Audio, Si Queres Una De Estas Canciones Asegurate De Saber La Letra Ya Que No Va A Aparecer En La Pantalla... A.Q.M Resistire ABEL PINTOS Aventura Cactus La Llave Por Una Gota De Tu Voz Todo Esta En Vos ABUELOS DE LA NADA Costumbres Argentinas Lunes Por La Madrugada Mil Horas Sin Gamulan ADELE Make You Feel My Love Set Fire To The Rain Someone Like You Turning Tables AGAPORNIS Donde Están Corazon Por Amarte Asi Si Te Vas Tan Solo Tu Todo Esta En Vos AGUSTIN ALMEYDA En Tí Nunca Mas ALCIDES Violeta ALEJANDRO FERNANDEZ Amor Gitano - Beyonce - Alejandro Fernandez - Canta Corazon Me Dedique A Perderte (Salsa) Me Dedique A Perderte Que Lastima Si Tu Supieras Te Voy A Perder ALEJANDRO FILIO Vienes Con El Sol ALEJANDRO LERNER Amarte Asi Despues De Ti Mil Veces Lloro Todo A Pulmon Volver A Empezar ALEJANDRO SANZ Amiga Mia Aprendiz Corazon Partido Cuando Nadie Me Ve El Alma Al Aire Pisando Fuerte Quiero Morir En Tu Veneno SI TU ME MIRAS Una Noche - Corrs Y Alejandro Sanz Viviendo De Prisa Y Si Fuera Ella Y Solo Se Me Ocurre Amarte ALEKS SINTEK Duele El Amor Te Soñe ALEX UBAGO A Gritos De Esperanza Aunque No Te Pueda Ver Dame Tu Aire Me Arrepiento Por Esta Ciudad Que Pides Tu Sabes Siempre En Mi Mente Sin Miedo A Nada - Alex Ubago Y Natali ALEXANDER ACHA Te Amo ALEXANDRE PIRES Amame Usted Se Me Llevo La Vida AMAR AZUL El Polvito Yo Me Enamore AMARAL Como Hablar Dias De Verano El Universo Sobre Mí Si Tu No Vuelves - Amaral Y Chetes (Miguel Bose) Sin Ti No Soy Nada Te Necesito ANDREA BOCELLI -

¿Donde Está La Música Chilena? * Entrevistas A

* ¿Donde está la música chilena? * Entrevistas a Margot Loyola, José Oplustil, Rodrigo Torres, José Perez de Arce y Claudio Mercado * ¿Tiene ritmo la historia de Chile? * Escriben Rodolfo Parada-Lillo, Octavio Hasbún, Fabio Salas y David Ponce Dirección de Bibliotecas, Archivos y Museos # 49 Año XIII Primavera 2008 $1.600 yo no canto por cantar... Patrimonio Cultural N° 49 (Año XIII) Primavera de 2008 Revista estacional de la Dirección de Bibliotecas, Archivos y Museos (Dibam), Ministerio de Educación de Chile. Directora y representante legal: Nivia Palma. Consejo editorial: Ricardo Abuauad, José Bengoa, Marta Cruz Coke, Diamela Eltit, Humberto Giannini, Ramón Griffero, Pedro Güell, Marta Lagos, Pedro Milos, Jorge Montealegre, Micaela Navarrete y Pedro Pablo Zegers. Comité editor: Claudio Aguilera, Grace Dunlop, Gloria Elgueta, Michelle Hafemann, Virginia Jaeger, Leonardo Mellado y Delia Pizarro. Colaboran: Gabinete y Departamento de Prensa y RR.PP. Dibam; Extensión Cultural de la Biblioteca Nacional; Museo Histórico Nacional. Editora: Grace Dunlop ([email protected]). Periodista: Virginia Jaeger ([email protected], [email protected]). Ventas y suscripciones: Myriam González ([email protected]) Carmen Santa María ([email protected]) Diseño: Junta Editorial de las Comunas Unidas (www.juntaeditorial.cl) Corrección de textos: Héctor Zurita Dirección: Alameda Bernardo O’Higgins 651 (Biblioteca Nacional, primer piso), Santiago de Chile. Teléfonos: 360 53 84 – 360 53 30 Fono-Fax: 632 48 03 Correo electrónico: [email protected] Sitio web: www.patrimoniocultural.cl En el diseño de esta publicación se utilizan las tipografías Fran Pro de Francisco Gálvez y Digna Sans de Rodrigo Ramírez, ambos pertenecientes al colectivo www.tipografia.cl Esta revista tiene un tiraje de 5.000 ejemplares que se distribuyen en todo el país, a través de la red institucional de la Dibam, suscripciones y librerías. -

Por El Mejor Camino

Diario del AltoAragón Domingo, 10 de agosto de 2008 Domingo 15 A todo ritmo Kudai / El grupo chileno publica un nuevo disco, ‘Nhada’, y prepara gira mundial Fiebre adolescente ESTOS CHICOS, QUE EMPEZARON HACIENDO VERSIONES ITALIANAS, HAN SIDO PREMIADOS POR LA MTV LATINOAMÉRICA COMO MEJOR GRUPO POP, Y ACUMULAN DISCOS DE ORO Y PLATINO COMO SI NADA. HA LLEGADO EL MOMENTO DE SU CONFIRMACIÓN. El joven grupo Kudai nació en el año 2000 bajo el nombre de Ciao, y acaba de sacar su tercer trabajo: Nhada. La banda Kudai, que significa minaciones a los Premios MTV dos premios en los MTV Vídeos Gran parte de las composicio- mocional, Kudai desea ser la voz “joven trabajador” en la lengua Latinoamérica y ser disco de pla- Musicales Latinoamérica, como nes del disco, que salió a la venta juvenil que canta “más allá de de los indígenas sur-americanos tino por sus ventas en Chile. Mejor artista pop y Mejor artista en Estados Unidos y Puerto Rico hablar del amor”, pues el tema mapuche, nació en el año 2000 Con su segundo trabajo, So- central. el pasado martes, fueron escritas aborda el tema del calentamiento bajo el nombre de Ciao. Canta- brevive (2006), obtuvieron un El reto de comenzar en un junto con el compositor chile- global. ban temas de grupos italianos, disco de oro en Chile y vendie- nuevo país y con el apoyo de la no Koko Stambuk. “Es un tipo Además se valieron de la expe- pero con arreglos diferentes para ron unas 350.000 copias en todo discográfica multinacional EMI que de ideas súper locas, agarra riencia del reconocido productor que los niños pudieran escuchar- el mundo. -

Dur 13/07/2020

LUNES 13 DE JULIO DE 2020 2 ETCÉTERA TOP TOP SPOTIFY Kudai vuelve con BILLBOARD nuevos sonidos para NO. 1 La jeepeta (remix) NO. 1 Anuel AA, Nio García y sus fans Myke Towers con Brray y Rockstar Juanka DaBaby y Roddy Ricch La agrupación retoma los escenarios con temas “refrescados”. NO. 2 NO. 2 Relación Whats Poppin Sech Jack Harlow NO. 3 NO. 3 Azul Blinding Lights J Balvin The Weeknd NO. 4 NO. 4 Blinding Lights Savage The Weeknd Megan Thee Stallion y NO. 5 Beyonce Safaera NO. 5 BadBunny,Jowell& Randy y Nengo Flow Roses SAINt JHN NO. 6 Yoperreo sola NO. 6 AGENCIAS Bad Bunny Say So EFE Doja Cat y Nicki Minaj Santiago de Chile Inicios Premios Regreso NO. 7 Kudai se formó al La década de los 2000 Hace tres años Luego de una década de re- NO. 7 principio de los años los llevó a distintos decidieron retomar el ceso y para celebrar sus 20 Rojo 2000 integrado por paísesyacosechar proyecto y fue así que años de carrera, el grupo Intentions J Balvin Pablo Holman, Tomás galardones como Mejor en 2019 sacaron un de pop chileno Kudai re- Justin Bieber y Quavo Manzi, Bárbara artista en los Premios nuevo disco, titulado gresa con una nueva ver- Sepúlveda y Natalino MTV Latinoamérica. ‘Laberinto’. NO. 8 sión musical de su primer NO. 8 Elegí éxito, ‘Sin Despertar’, y con el deseo de no solo re- Watermelon vienen, ¿este material va El año pasado sacaron Dalex, Dímelo Flow, conectar con sus fans his- cia, pero creo que en gene- Sugar Lenny Tavárez, Rauw tóricos, sino de llegar a las dirigido a los fanáticos ral la música es atemporal un nuevo álbum y se ha Alejandro generaciones más jóvenes. -

The Identity of the British Immigrants in Valparaíso in the Star of Chile

THE IDENTITY OF THE BRITISH IMMIGRANTS IN VALPARAÍSO 1 Universidad de Chile Facultad de Filosofía y Humanidades Departamento de Lingüística The Identity of the British immigrants in Valparaíso in The Star of Chile (1904-1906) Informe final de Seminario de Grado para optar al grado de Licenciado en Lengua y Literatura Inglesas Autores Cristian Andres Arancibia Lagos Lucia Paz Araya Machuca Jenisse Carolina Cárdenas Soto Constanza Antonia Escaida Solis Saggia Alessandra Failla Cubillos Luz María Ignacia Martínez Altamirano Michela del Pilar Rojas Madrid Malva Soto Blamey Profesora guía Ana María Burdach R. Santiago, Chile Diciembre, 2017 THE IDENTITY OF THE BRITISH IMMIGRANTS IN VALPARAÍSO 2 Abstract The study of identity has been widely examined within several fields of linguistics and also among the social sciences. However discourse analysis applied to newspapers is a relatively recent field. Thus, the present study based on the framework of evaluation in language developed by Martin and Rose (2008) focuses on the means by which editorials of the newspaper The Star of Chile convey a sense of identity of the British community in Valparaíso at the turn of the 20th century. To develop this study, five editorials of the The Star of Chile from the years 1904, 1905 and 1906 were selected for the analysis. Each of them representing relevant aspects of the British immigrants’ culture, religious and political beliefs, and significant historical events of that time. The analysis included the tracking of the participants and the options used by the author for their appraisal with the aim of unveiling their identity. The results elucidate how the British immigrants perceived themselves and how they depicted those outside their immediate community at the beginning of the twentieth-century in Valparaiso. -

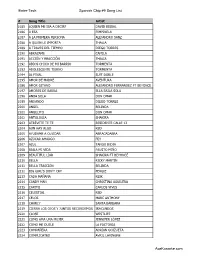

Hetcmmcps9 Song List

Enter-Tech Spanish Chip #9 Song List # Song Title Artist 2185 ¿QUIEN ME IBA A DECIR? DAVID BISBAL 2186 A ESA PIMPINELA 2187 A LA PRIMERA PERSONA ALEJANDRO SANZ 2188 A QUIEN LE IMPORTA THALIA 2189 A TRAVES DEL TIEMPO DIEGO TORRES 2190 ABRAZAME CAMILA 2191 ACCIÓN Y REACCIÓN THALIA 2192 ADIOS CHICO DE MI BARRIO TORMENTA 2193 ADOLESCENTE TIERNO TORMENTA 2194 AL FINAL SUIT DOBLE 2195 AMOR DE MADRE AVENTURA 2196 AMOR GITANO ALEJANDRO FERNANDEZ FT BEYONCE 2197 AMORES DE BARRA ELLA BAILA SOLA 2198 ANDA SOLA DON OMAR 2199 ANDANDO DIEGO TORRES 2200 ANGEL BELINDA 2201 ANGELITO DON OMAR 2202 ANTOLOGÍA SHAKIRA 2203 ATRÉVETE TE TE RESIDENTE CALLE 13 2204 AUN HAY ALGO RBD 2205 AYUDAME A OLVIDAR ABRACADABRA 2206 AZÚCAR AMARGO FEY 2207 AZUL TANGO INDIA 2208 BAILA MI VIDA FAUSTO MIÑO 2209 BEAUTIFUL LIAR SHAKIRA FT BEYONCÉ 2210 BELLA RICKY MARTIN 2211 BELLA TRAICIÓN BELINDA 2212 BIG GIRL'S DON'T CRY FERGIE 2213 CADA MAÑANA REIK 2214 CANDY MAN CHRISTINA AGUILERA 2215 CARITO CARLOS VIVES 2216 CELESTIAL RBD 2217 CELOS MARC ANTHONY 2218 CHARLY SANTA BÁRBARA 2219 CIERRA LOS OJOS Y JUNTOS RECORDEMOS IRACUNDOS 2220 CLOSE WESTLIFE 2221 COMO AMA UNA MUJER JENNIFER LÓPEZ 2222 COMO ME DUELE LA FACTORIA 2223 COMPAÑERA ADRIAN GOIZUETA 2224 COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVINGNE AceKaraoke.com Enter-Tech Spanish Chip #9 Song List 2225 CONDICIÓN ABRACADABRA 2226 CORAZÓN RICKY MARTIN 2227 CORAZÓN ES UN GITANO NICOLA DI BARI 2228 CUANDO LOS SAPOS BAILEN FLAMENCO ELLA BAILA SOLA 2229 CUANDO NO ES CONTIGO CHRISTINA AGUILERA 2230 CUANDO VOLVERÁS AVENTURA 2231 CUMBIA DE LOS ABURRIDOS CALLE -

Campbell, Joseph

El héroe de las mil caras PSICOANÁLISIS DEL MITO FONDO DE CULTURA ECONÓMICA MÉXICO Primera edición en inglés, 1949 Primera edición en español, 1959 Primera reimpresión, 1972 Traducción de LUISA JOSEFINA HERNÁNDEZ Título de esta obra The Hero with a Thousand Faces . © 1949 Bollingen Foundation Inc., Nueva York D. R. © 1959 FONDO DE CULTURA ECONÓMICA Av. de la Universidad 975, México 12, D. F. Impreso en México Nota de esta edición digital : Entre corchetes se ubica el paginado original, como si el número estuviera en la parte superior de la página. 2 ÍNDICE PREFACIO ............................................................................................................................................................... 8 PRÓLOGO.............................................................................................................................................................. 10 EL MONOMITO.................................................................................................................................................... 10 1. El mito y el sueño............................................................................................................................................. 10 2. Tragedia y comedia .......................................................................................................................................... 22 3. El héroe y el dios ............................................................................................................................................. -

Music Guide Music HISTORY There Was a Time When “Elevator Music” Was All You Heard in a Store, Hotel, Or Other Business

Music Guide Music HisTORY There was a time when “elevator music” was all you heard in a store, hotel, or other business. Yawn. 1 1971: a group of music fanatics based out of seattle - known as Aei Music - pioneered the use of music in its original form, and from the original artists, inside of businesses. A new era was born where people could enjoy hearing the artists and songs they know and love in the places they shopped, ate, stayed, played, and worked. 1 1985: DMX Music began designing digital music channels to fit any music lover’s mood and delivered this via satellite to businesses and through cable TV systems. 1 2001: Aei and DMX Music merge to form what becomes DMX, inc. This new company is unrivaled in its music knowledge and design, licensing abilities, and service and delivery capability. 1 2005: DMX moves its home to Austin, TX, the “Live Music capital of the World.” 1 Today, our u.s. and international services reach over 100,000 businesses, 23 million+ residences, and over 200 million people every day. 1 DMX strives to inspire, motivate, intrigue, entertain and create an unforgettable experience for every person that interacts with you. Our mission is to provide you with Music rockstar service that leaves you 100% ecstatic. Music Design & Strategy To get the music right, DMX takes into account many variables including customer demographics, their general likes and dislikes, your business values, current pop culture and media trends, your overall décor and design, and more. Our Music Designers review hundreds of new releases every day to continue honing the right music experience for our clients. -

Se Queda Silvia Navarro

10949669 05/14/2007 10:40 p.m. Page 1 Televisión: Las mujeres llevan la batuta en “Sexo y otros secretos” | Pág. 3 Martes 15 de mayo de 2007 B Editor: EMMANUEL FÉLIX LESPRÓN Coeditor Gráfico: JESÚS ESPINOZA [email protected] “Sobrevive”SENCILLO | “DÉJAME GRITAR”, PRIMER CORTE DEL NUEVO DISCO SEMANA INTENSA GABRIELA Entérate de las actividades culturales ■ Edad: 22 años. que se avecinan estos días. ■ Le encanta ir al cine y es fan del cine latino. CULTURALES 4 ■ Entre sus actividades favoritas están hacer yoga, trotar y leer. ■ Como pasa mucho tiempo fuera de casa, utiliza el Internet para chatear con sus familiares y KudaiKudai amigos. Cuarteto chileno visitará México como parte de ando y viviendo. Muchas veces ■ Está en el medio desde muy ellos no se atreven a decirlo por pequeña: A los tres años hizo la promoción de su segundo álbum de estudio miedo al rechazo de la sociedad comerciales, luego tomó clases o de sus padres. de actuación e incluso tuvo la AGENCIA REFORMA rrera como solista en Ecuador. “Es mucha responsabilidad. oportunidad de participar en una A la cantante la conocieron Yo misma me he sentido un po- telenovela colombiana. MONTERREY, NUEVO LEÓN.- El gru- cuando ella les abrió una pre- co sicóloga de personas que han po chileno Kudai voló con su pri- sentación en su país. Al irse Ni- estado en problemas súper se- mer disco por los cielos de Lati- cole por motivos personales, la rios. Por ejemplo, gente cercana Aunque aumentan los rumores del cambio de noamérica y luego sobrevivió al invitación fue cedida a Gabriela. -

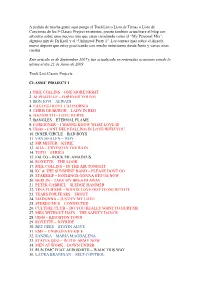

Tracklist Classic Project | Nanoblog.Net

A pedido de mucha gente aqui pongo el TrackList o Lista de Temas o Lista de Canciones de los 9 Classic Project existentes, pronto tambien actualizare el blog con articulos sobre unos nuevos mix que estan circulando como el “My Personal Mix”, algunos mix de Dj Kroll y el “Unlimited Party 1″. Les contare mas sobre el Airsoft, nuevo deporte que estoy practicando con mucho entusiasmo desde Junio y varias otras cositas. Este articulo es de Septiembre 2007 y fue actualizado en reiteradas ocasiones siendo la ultima el dia 21 de Junio de 2009. Track List Classic Projects CLASSIC PROJECT 1 1. PHIL COLLINS – ONE MORE NIGHT 2. ALPHAVILLE – FOREVER YOUNG 3. BON JOVI – ALWAYS 4. EAGLES-HOTEL CALIFORNIA 5. CHRIS DE BURGH – LADY IN RED 6. NAZARETH – LOVE HURTS 7. BANGLES – ETERNAL FLAME 8. FOREIGNER – I WANNE KNOW WHAT LOVE IS 9. UB40 – CANT HELP FALLING IN LOVE WITH YOU 10. INNER CIRCLE – BAD BOYS 11. VAN HEALEN – WHY 12. MR MISTER – KYRIE 13. AHA – CRYING IN THE RAIN 14. TOTO – AFRICA 15. FALCO – ROCK ME AMADEUS 16. ROXETTE – THE LOOK 17. PHIL COLLINS – IN THE AIR TONIGHT 18. KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND – PLEASE DONT GO 19. STARSHIP – NOTHINGS GONNA STO US NOW 20. BERLIN – TAKE MY BREATH AWAY 21. PETER GABRIEL – SLEDGE HAMMER 22. TINA TURNER – WHATS LOVE GOT TO DO WITH IT 23. TEARS FOR FEARS – SHOUT 24. MADONNA – JUSTIFY MY LOVE 25. STEREO MCS – CONNECTED 26. CULTURE CLUB – DO YOU REALLY WANT TO HURT ME 27. MEN WITHOUT HATS – THE SAFETY DANCE 28. UB40 – KINGSTON TOWN 29. -

Visual Foxpro

THE LATIN ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS 9th Annual Latin GRAMMY ® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year July 1, 2007 through June 30, 2008 The following information is confidential and is not to be copied, loaned or otherwise distributed. ACADEMIA LATINA DE ARTES Y CIENCIAS DE LA GRABACION, INC. LISTA FINAL DE NOMINACIONES 9a. Entrega Anual del Latin GRAMMY ® Para grabaciones lanzadas durante el año de elegibilidad 1° de julio del 2007 al 30 de junio del 2008 La siguiente información es confidencial y no debe ser copiada, prestada o distribuida de ninguna forma ACADEMIA LATINA DAS ARTES E CIÊNCIAS DA GRAVAÇÃO, INC. LISTA FINAL DOS INDICADOS 9 a Entrega Anual do Latin GRAMMY® Para gravações lançadas durante o Ano de Elegibilidade 1° de julho de 2007 a 30 de junho de 2008 As informações aqui contidas são confidenciais e não devem ser copiadas, emprestadas ou distribuídas por nenhum meio General Field Category 1 Category 2 Record Of The Year Album Of The Year Grabación Del Año Album Del Año Gravação Do Ano Álbum Do Ano Award to the Artist and to the Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s) Award to the Artist(s), and to the Album Producer(s), Recording and/or Mixer(s) if other than the artist. Engineer(s) / Mixer(s) & Mastering Engineer(s) if other than the artist. Premio al Artista(s), Productor(es) del Album y al Ingeniero(s) de Grabación. Premio al Artista(s), Productor(es) del Album y al Ingeniero(s) de Prêmios ao(s) Artista(s), Produtor(es) do Álbum e Engenheiro(s) de Grabación, Ingeniero(s) de Mezcla y Masterizadores, si es(son) otro(s) Gravação. -

Directv Arena Para Para El 24 De Noviembre

Prensario música & video | Septiembre 2017 Prensario música & video | Septiembre 2017 Prensario música & video | Septiembre 2017 Prensario música & video | Septiembre 2017 Prensario música & video | Septiembre 2017 Prensario música & video | Septiembre 2017 editorial ARGENTINA / AGENDA / SHOWBUSINESS Ratones Paranoicos, Bon Jovi, U2, Monsters of Rock, B.A.Rock, Axel al Hipódromo de Palermo y Abel a River Bolivia, en digital LO NACIONAL DICE PRESENTE PESE A LA AFLUENCIA ANGLO Y LATINA El nutrido showbusiness argentino, tuvo tres y 17 de noviembre en el Estadio Unico y a Harry 29 de octubre en el Luna Park y Franco de Vita noticias recientes. Por un lado el anuncio del Ri- Styles, el ex1D en el mismo DirecTV Arena para para el 24 de noviembre. ste es un momento de la industria discográfica en el También está la manera diferente de lanzar un disco, que ver de Abel con Move Concerts, que como con el 24 de mayo 2018. El próximo Lollapalooza en En el Luna Park, sobresalen Lisandro Aristimu- que la música digital dio finalmente sus frutos y el no es novedad pero se va extendiendo. Los deejays o los la Beriso vuelve a ser el canal para que las figu- marzo tendrá tres días y agota rápidamente to- ño el 16 de septiembre y Ciro y los Persas el 11 Esoporte físico sintió la anunciada caída, si bien tiene grupos bailables o de regaetón/música urbana hace tiempo ras locales vuelvan al estadio de Nuñez u Obras, das sus instancias de preventa. de octubre también de 300. Luego Karina el 14 aun elementos para recuperarse.