Anupama Rao Violence and Humanity: Or, Vulnerability As Political Subjectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Intro. (Final).P65

INTRODUCTION 11 1 Introduction UNDERSTANDING CASTES TO ANNIHILATE THEM Khairlanji. An obscure village in the unheard of Mohadi taluk of Bhandara district, Maharashtra. Suddenly, in 2006, it became the newest addition to the series of names that have become synonymous with violent crimes against dalits in post- independence India—Kilvenmani (44 dalits burnt alive in Tamil Nadu, 1968), Belchi (14 dalits burnt alive in Bihar, 1977), Morichjhanpi (hundreds of dalit refugees massacred by the state in Sundarbans, West Bengal, 1978), Karamchedu (six dalits murdered, three dalit women raped and many more wounded in Andhra Pradesh, 1984), Chundru (nine dalits massacred and dumped in a canal in Andhra Pradesh, 1991), Melavalavu (an elected dalit panchayat leader and five dalits murdered, Tamil Nadu, 1997), Kambalapalli (six dalits burnt alive in Karnataka, 2000) and Jhajjar (five dalits lynched near a police station in Haryana, 2003). The incidents listed here may not figure in any history of post-independence India. Most Indians may not even have heard of these places. Khairlanji, too, may soon be similarly forgotten. This book is an effort to ensure that it will not be easily erased from memory. As Milan Kundera says, the struggle against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting. 12 KHAIRLANJI Khairlanji ignited dalit anger and spawned agitations all over Maharashtra and beyond—spontaneous protests that erupted on the streets and were led by ordinary people, sans leaders. It was unlike anything Maharashtra had seen before. This book -

Unheard Voices -DALIT WOMEN

Unheard Voices -DALIT WOMEN An alternative report for the 15th – 19th periodic report on India submitted by the Government of Republic of India for the 70th session of Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Geneva, Switzerland Jan, 2007 Tamil Nadu Women’s Forum 76/37, G-1, 9th Street, "Z" Block, Anna Nagar West, Chennai, 600 040, Tamil Nadu, INDIA Tel: +91-(0)44-421-70702 or 70703, Fax: +91-(0)44-421-70702 E-mail: [email protected] Tamil Nadu Women's Forum is a state level initiative for women's rights and gender justice. Tamil Nadu Women's Forum (TNWF) was started in 1991 in order to train women for more leadership, to strengthen women's movement, and to build up strong people's movement. Tamil Nadu Women’s Forum is a member organization of the International Movement against All forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR), which has consultative status with UN ECOSOC (Roster). Even as we are in the 21st millennium, caste discrimination, an age-old practice that dehumanizes and perpetuates a cruel form of discrimination continues to be practiced. India where the practice is rampant despite the existence of a legislation to stop this, 160 million Dalits of which 49.96% are women continue to suffer discrimination. The discrimination that Dalit women are subjected to is similar to racial discrimination, where the former is discriminated and treated as untouchable due to descent, for being born into a particular community, while, the latter face discrimination due to colour. The caste system declares Dalit women as ‘impure’ and therefore untouchable and hence socially excluded. -

Ambedkarite Productions of Space

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 31–50 brandeis.edu/j-caste October 2020 ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i2.199 Leisure, Festival, Revolution: Ambedkarite Productions of Space Thomas Crowley1 Abstract This article analyzes the town of Mahad in the state of Maharashtra, using it as a lens to examine protests and commemorations that are inseparable from Ambedkarite and Neo-Buddhist transformations of space. A key site of anti-caste struggle, Mahad witnessed two major protests led by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar in 1927: the claiming of water from Chavdar Tale, a tank located in a upper caste neighbourhood; and the burning of the Manusmriti. These events are commemorated every year with large-scale festivities. The article analyzes the ways that these protests and festivities have worked to produce a distinctly Ambedkarite space, one that is radically counterposed to hierarchical, Brahminical productions of space. Exploring the writings of Ambedkar and more recent Ambedkarite scholars, and putting these texts into dialogue with the spatial theories of Henri Lefebvre, the article contributes to a growing international literature on the spatiality of caste. The Navayana Buddhism pioneered by Ambedkar has been analyzed in terms of its ideology, its pragmatism, and its politics, but rarely in terms of its spatiality. Drawing on Lefebvre helps flesh out this spatial analysis while a serious engagement with neo-Buddhist practices helps to expand, critique and globalize some of Lefebvre’s key claims. Keywords Ambedkar, Lefebvre, Mahad, neo-Buddhism, festival, revolution Introduction The market town of Mahad sits on a small plateau in the foothills of the Sahyadri mountains in the western Indian state of Maharasthra. -

Buddhism and the Global Bazaar in Bodh Gaya, Bihar

DESTINATION ENLIGHTENMENT: BUDDHISM AND THE GLOBAL BAZAAR IN BODH GAYA, BIHAR by David Geary B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1999 M.A., Carleton University, 2003 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2009 © David Geary, 2009 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a historical ethnography that examines the social transformation of Bodh Gaya into a World Heritage site. On June 26, 2002, the Mahabodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gaya was formally inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. As a place of cultural heritage and a monument of “outstanding universal value” this inclusion has reinforced the ancient significance of Bodh Gaya as the place of Buddha's enlightenment. In this dissertation, I take this recent event as a framing device for my historical and ethnographic analysis that details the varying ways in which Bodh Gaya is constructed out of a particular set of social relations. How do different groups attach meaning to Bodh Gaya's space and negotiate the multiple claims and memories embedded in place? How is Bodh Gaya socially constructed as a global site of memory and how do contests over its spatiality im- plicate divergent histories, narratives and events? In order to delineate the various historical and spatial meanings that place holds for different groups I examine a set of interrelated transnational processes that are the focus of this dissertation: 1) the emergence of Buddhist monasteries, temples and/or guest houses tied to international pilgrimage; 2) the role of tourism and pilgrimage as a source of economic livelihood for local residents; and 3) the role of state tourism development and urban planning. -

Life & Mission Dr B R Ambedkar Compiled by Sanjeev Nayyar

Life & Mission Dr B R Ambedkar Compiled by Sanjeev Nayyar March 2003 Book by Dhananjay Keer Courtesy & Copyright Popular Prakashan For those of us born after 1950 Dr Ambedkar is mostly remembered to as the Father of the Indian Constitution. He is also referred to as the Savior of the Depressed Classes called Dalits today. I had always wanted to read about him but the man aroused me after I read his book ‘Thoughts on Pakistan’. His style is well researched, simple, straight possibly blunt. He came across as a very well read person whose arguments were based on sound logic. After completing the book I was in awe of the man’s intellect. Where did this Man come from? Why do the depressed classes worship him today? What were the problems that he had to undergo? Why did he become a Buddhist? What were his views on Ahimsa? Not knowing whether any book would satisfy my quest for knowledge I went to my favorite bookshop at the Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan & was fortunate to find a book by D Keer. Having read Life Story of Veer Savarkar by the same author I instinctively knew that this was the book. Dr Ambedkar is referred to as BRA & Depressed Classes as DC henceforth. How have I compiled this piece? Done a précis of the book taking the most important events in BRA’s life. Focused on the problems faced by him, his achievements, dual with Gandhi, role in India’s Independence movement & framing India’s Constitution, reasons for embracing Buddhism. The book also has extensive quotations from historic interviews & inspiring speeches. -

Dr. Deepak Pawar

Dr. Deepak Pawar Department of Civics & Politics, Mumbai University Pherozshah Mehta Bhavan, Department of Civics & Politics, Kalina Campus, University of Mumbai, Santacruz (E), Mumbai – 400098 [email protected] 1 EDUCATION 1988 SSC Sarvoday Vidyalaya Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai 1990 HSC Kelkar Education Trust‟s V. G. Vaze College of Arts, Mulund, Mumbai Science & Commerce 1993 B. A. Kelkar Education Trust‟s V. G. Vaze College of Arts, Mulund, Mumbai Science & Commerce 1995 M. A. Department of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai Mumbai 1997 NET University Grants Commission Qualified 2013 PhD Department of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai Mumbai Teaching experience: 24 years Research experience: 24 years Subjects taught: Language Policy and Politics in India Language Policy and Politics: A comparison of India and Pakistan Public Administration Political Theory Theories of International Relations Indian Constitution Political Thoughts in Maharashtra Western Political Thought Local Self-government (with special reference to Maharashtra) Understanding Politics through Cinema Rights in the context of Maharashtra Dalit Movement in India Regionalism and Regional disparities in Maharashtra 2 Indian Government and Policy Contribution in teaching methods: Chalk and Talk method Assignments Classroom Debates Regular Class Test Visit to Documentation Centers for Screening of Documentaries Presentations Book Reviews Newspaper Clippings Poster Presentation Industrial Visits Participation in conference Evaluation Techniques: Class Test Home Assignments Viva Presentations PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Position Institution Assistant Professor Department of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai: 1. Language Policy and Politics 2. State Politics. Lecturer K. J. Somaiya College of Arts & Commerce, Mumbai: 1. Political Theory, 2. Politics in Maharashtra 3. International Relations. President Marathi Abhyas Kendra (Marathi Study Centre): An organization working for the promotion Marathi language and culture. -

A Comparative Study of Dalit Movements in Punjab and Maharashtra, India

Religions and Development Research Programme Religious Mobilizations for Development and Social Change: A Comparative Study of Dalit Movements in Punjab and Maharashtra, India Surinder S. Jodhka and Avinash Kumar Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Indian Institute for Dalit Studies, New Delhi Working Paper 47 - 2010 Religions and Development Research Programme The Religions and Development Research Programme Consortium is an international research partnership that is exploring the relationships between several major world religions, development in low-income countries and poverty reduction. The programme is comprised of a series of comparative research projects that are addressing the following questions: z How do religious values and beliefs drive the actions and interactions of individuals and faith-based organisations? z How do religious values and beliefs and religious organisations influence the relationships between states and societies? z In what ways do faith communities interact with development actors and what are the outcomes with respect to the achievement of development goals? The research aims to provide knowledge and tools to enable dialogue between development partners and contribute to the achievement of development goals. We believe that our role as researchers is not to make judgements about the truth or desirability of particular values or beliefs, nor is it to urge a greater or lesser role for religion in achieving development objectives. Instead, our aim is to produce systematic and reliable knowledge and better understanding of the social world. The research focuses on four countries (India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Tanzania), enabling the research team to study most of the major world religions: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism and African traditional belief systems. -

The Khairlanji Murders & India's Hidden Apartheid ANAND

** persistence «• The Khairlanji Murders & India's Hidden Apartheid ANAND TELTUMBDE This book exposes the gangrenous heart of Indian society. ARUNDHATI ROY © Anand Teltumbde's analysis of the public, ritualistic massacre of a dalit family in 21st century India exposes the gangrenous heart of our society. It contextualizes the massacre and describes the manner in which the social, political and state machinery, the police, the mass media and the judiciary all collude to first create the climate for such bestiality, and then cover it up. This is not a book about the last days of relict feudalism, but a book about what modernity means in India. It discusses one of the most important issues in contemporary India. —ARUNDHATI ROY, author of The God of Small Things This book is finally the perfect demonstration that the caste system of India is the best tool to perpetuate divisions among the popular classes to the benefit of the rulers, thus annihilating in fact the efficiency of their struggles against exploitation and oppression. Capitalist modernization is not gradually reducing that reality but on the opposite aggravating its violence. This pattern of modernization permits segments of the peasant shudras to accede to better conditions through the over-exploitation of the dalits. The Indian Left must face this major challenge. It must have the courage to move into struggles for the complete abolition of caste system, no less. This is the prerequisite for the eventual emerging of a united front of the exploited classes, the very first condition for the coming to reality of any authentic popular democratic alternative for social progress. -

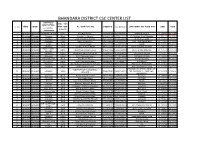

Bhandara District Csc Center List

BHANDARA DISTRICT CSC CENTER LIST ग्रामपंचायत/ झोन / वा셍ड महानगरपाललका Sr. No. जि쥍हा तालुका (फ啍त शहरी कᴂद्र चालक यांचे नाव मोबाईल क्र. CSC-ID/MOL- आपले सरकार सेवा कᴂद्राचा प配ता अ啍ांश रेखांश /नगरपररषद कᴂद्रासाठी) /नगरपंचायत 1 Bhandara Bhandara SHASTRI CHOUK Urban Amit Raju Shahare 9860965355 753215550018 SHASTRI CHOUK 21.177876 79.66254 2 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Avinash D. Admane 8208833108 317634110014 Dr. Mukharji Ward,Bhandara 21.1750113 79.65582 3 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Jyoti Wamanrao Makode 9371134345 762150550019 NEAR UCO BANK 21.174854 79.64352 4 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Sanjiv Gulab Bhure 9595324694 633079050019 CIVIL LINE BHANDARA 21.171533 79.65356 5 Bhandara Bhandara paladi Rural Gulshan Gupta 9423414199 622140700017 paladi 21.169466 79.66144 6 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban SUJEET N MATURKAR 9970770298 712332740018 RAJIV GANDHI SQUARE 21.1694655 79.66144 RAJIV GANDI 7 Bhandara Bhandara Urban Basant Shivshankar Bisen 9325277936 637272780014 RAJIV GANDI SQUARE 21.167537 79.65599 SQUARE 8 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Mohd Wasi Mohd Rafi Sheikh 8830643611 162419790010 RAJENDRA NAGAR 21.16685 79.655364) 9 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Kartik Gyaniwant Akare 9326974400 311156120014 IN FRONT OF NH6 21.166096 79.66028 10 Bhandara Bhandara Tekepar[kormbi] Rural Anita Eknath Bhure 9923719175 217736610016 Tekepar[kormbi] 21.1642922 79.65682 11 Bhandara Bhandara BHANDARA Urban Priya Pritamlal Kumbhare 9049025237 114534420013 BHANDARA 21.162895 79.64346 12 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Md. Sarfaraz Nawaz Md Shrif Sheikh 8484860484 365824810010 POHA GALI,BHANDARA 21.162768 79.65609 13 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Nitesh Natthuji Parate 9579539546 150353710012 Near Bhandara Bus Stop 21.161485 79.65576 FRIENDLY INTERNET ZONE, Z.P TARKESHWAR WASANTRAO 14 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban 9822359897 434443140013 SQ. -

Khairlanji Killings: Bombay HC Commutes Death Sentence of 6 Convicts to Life Term -

Khairlanji killings: Bombay HC commutes death sentence of 6 convicts to life term - ... Side 1 af 1 Printed from Khairlanji killings: Bombay HC commutes death sentence of 6 convicts to life term TIMES NEWS NETWORK & AGENCIES, Jul 14, 2010, 11.14am IST NEW DELHI: The Nagpur bench of Bombay high court on Wednesday commuted death sentence of 6 convicts in the gruesome Khairlanji Dalit family massacre case of 2006 to life imprisonment. The life imprisonment to the accused will be for a period of 25 years, including the time they have already served in prison. A division bench comprising Justices A P Lawande and R C Chauhan pronounced the much-awaited final verdict in the case, turning down a plea by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) challenging the lower court's ruling giving life to two of the eight accused while sentencing to death six people. The judgement was delivered via video conferencing as one of the judges of the division bench Justice Ravindra Chavan is posted at Mumbai. Earlier, Bhandara sessions court had awarded capital punishment to 6 accused and lifer to 2. Those given death were Shatrughana Dhande, Vishwanath Dhande, Ramu Dhande, Sakru Binjewar, Jagdish Mandlekar and Prabhkar Mandlekar. The trial court had given life term to Shishupal Dhande and Gopal Binjewar. Three more accused were acquitted. The horrific incident unfolded on the evening of September 29, 2006, when a group of villagers descended on the Bhotmange family in Khairlanji village in Maharashtra's Bhandara district, IANS reported. They dragged out Surekha Bhaiyyalal Bhotmange, 44, her sons Roshan, 23, Sudhir, 21 and daughter Priyanka, 18, assaulted them brutally, paraded them naked in the village, sexually abused them with sticks and then hacked them to death. -

Understanding Sexual Violence As a Form of Caste Violence

Understanding sexual violence as a form of caste violence Prachi Patil Jawaharlal Nehru University Abstract The paper attempts to understand narratives of sexual violence anchored within the dynamics of social location of caste and gender. Apparent caste-patriarchy and gender hierarchies which are at play in cases of sexual violence against lower-caste and dalit women speak about differential experiences of rape and sexual abuse that women have in India. The paper endeavours to establish that sexual violence is also a form of caste violence by rereading the unfortunate cases of Bhanwari Devi, Khairlanji, Lalasa Devi and Delta Meghwal Keywords: caste-patriarchy, Dalit women, POA Act, rape, sexual violence The caste system has always been the spine of Indian social stratification. It continues to shape the everyday life of the majority of Indians. Caste rules and norms not only colour the daily functioning of village life, but they have also successfully penetrated into modern day life. The Indian caste system classifies individuals in descending order of hierarchy into four mutually exclusive varnas –the Brahmins (priests), the Kshatriyas (warriors), the Vaishyas (merchants) and the Shudras (servants), beyond these four castes is the fifth caste of the Ati- Shudras or the achhoots (untouchables). The formerly untouchable castes are also known as Dalits1. Jodhka (2012) notes that these four or five categories occupied different positions in the status hierarchy, with the Brahmans at the top, followed by the other three varnas in the order mentioned above, with the achhoots occupying a position at the very bottom. Membership into these castes is solely based on the accidental factor of birth. -

In the High Court of Judicature at Bombay, Nagpur Bench, Nagpur

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY, NAGPUR BENCH, NAGPUR. Criminal Confirmation Case No. 4/2008. Central Bureau of Investigation (Through D.S.P.,C.B.I.S.C.B. Chennai) Camp at Bhandara. ¼..Appellant. .versus. 1. Sakru Mahagu Binjewar (Original Accused No.2) 2. Shatrughna Isram Dhande (Original Accused No. 3) 3. Vishwanath Hagru Dhande (Original Accused No. 6) 4. Ramu Mangru Dhande (Original Accused No. 7) 5. Jagdish Ratan Mandlekar (Original Accused No. 8) 6. Prabhakar Jaswant Mandlekar (Original Accused No. 9) Respondent Nos. 1 to 6 R/o: Khairlanji District: Bhandara (Maharashtra State). ...Respondents BombayMr. Ejaz Khan, Spl. P.P. ForHigh appellant. Court Mr. Sudip Jaiswal, Advocate for respondent nos. 1,5 and 6. Mr. N.S.Khandewale, Advocate for respondent nos. 2,3 and 4. ::: Downloaded on - 12/09/2013 11:54:42 ::: 2 Criminal Appeal No. 748/2008 1. Shatrughna s/o Isram Dhande Aged about 40 years. Occupation: Agricultural Labourer. (Original accused no. 3) 2. Vishwanath s/o Hagru Dhande Aged 55 years. Occupation: Agricultural Labourer. (Original accused no. 6) 3. Ramu s/o Mangru Dhande Aged 42 years. Occupation; Agricultural Labourer. (Original accused no.7) 4. Shishupal s/o Vishwanath Dhande, aged 20 years. Occupation: Agricultural Labourer. (Original accused no. 11) (All the appellants are R/o: Village Khairlanji, Tah. Mohadi, Distr.Bhandara.) ¼....Appellants. .versus. The Central Bureau of Investigation, through its Dy.S.P., C.B.I., S.C.B., Chennai, Camp at Bhandara. Bombay High¼....Respondent. Court Mr. N.S.Khandewale Advocate for the appellants. Mr. Ejaz Khan, Spl.