1. Intro. (Final).P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unheard Voices -DALIT WOMEN

Unheard Voices -DALIT WOMEN An alternative report for the 15th – 19th periodic report on India submitted by the Government of Republic of India for the 70th session of Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Geneva, Switzerland Jan, 2007 Tamil Nadu Women’s Forum 76/37, G-1, 9th Street, "Z" Block, Anna Nagar West, Chennai, 600 040, Tamil Nadu, INDIA Tel: +91-(0)44-421-70702 or 70703, Fax: +91-(0)44-421-70702 E-mail: [email protected] Tamil Nadu Women's Forum is a state level initiative for women's rights and gender justice. Tamil Nadu Women's Forum (TNWF) was started in 1991 in order to train women for more leadership, to strengthen women's movement, and to build up strong people's movement. Tamil Nadu Women’s Forum is a member organization of the International Movement against All forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR), which has consultative status with UN ECOSOC (Roster). Even as we are in the 21st millennium, caste discrimination, an age-old practice that dehumanizes and perpetuates a cruel form of discrimination continues to be practiced. India where the practice is rampant despite the existence of a legislation to stop this, 160 million Dalits of which 49.96% are women continue to suffer discrimination. The discrimination that Dalit women are subjected to is similar to racial discrimination, where the former is discriminated and treated as untouchable due to descent, for being born into a particular community, while, the latter face discrimination due to colour. The caste system declares Dalit women as ‘impure’ and therefore untouchable and hence socially excluded. -

Anupama Rao Violence and Humanity: Or, Vulnerability As Political Subjectivity

Anupama Rao Violence and Humanity: Or, Vulnerability as Political Subjectivity the ghastliest incidence of sexual violence in recent memory in India’s Maharashtra state occurred on September 29, 2006 in the village of Khairlanji, Bhandara district. What began as a land grab by local agriculturalists ended in the rape and mutilation of 44-year-old Surekha Bhotmange and her teenaged student daughter, Priyanka, and the brutal murder of Surekha’s two sons, Roshan and Sudhir, ages 19 and 21, respectively. By all accounts, this was an upwardly mobile Dalit family.1 Sudhir was a graduate. He worked as a laborer with his visually impaired brother to earn extra money. Priyanka had completed high school at the top of her class. However, the family was paraded naked, beaten, stoned, sexually abused, and then murdered by a group of men from the Kunbi and Kalar agricultural castes. Surekha and her daughter, Priyanka, were bitten, beaten black and blue, and gang-raped in full public view for an hour before they died. Iron rods and sticks were later inserted in their genitalia. The private parts and faces of the young men were disfigured. “When the dusk had settled, four bodies of this dalit family lay strewn at the village choupal [square], with the killers pump- ing their fists and still kicking the bodies. The rage was not over. Some angry men even raped the badly mutilated corpses of the two women” (Vidarbha Jan Andolan Samiti 2006). The bodies were later scattered at the periphery of the village. social research Vol. 78 : No. 2 : Summer 2011 607 It took more than a month for the news to spread. -

Dr. Deepak Pawar

Dr. Deepak Pawar Department of Civics & Politics, Mumbai University Pherozshah Mehta Bhavan, Department of Civics & Politics, Kalina Campus, University of Mumbai, Santacruz (E), Mumbai – 400098 [email protected] 1 EDUCATION 1988 SSC Sarvoday Vidyalaya Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai 1990 HSC Kelkar Education Trust‟s V. G. Vaze College of Arts, Mulund, Mumbai Science & Commerce 1993 B. A. Kelkar Education Trust‟s V. G. Vaze College of Arts, Mulund, Mumbai Science & Commerce 1995 M. A. Department of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai Mumbai 1997 NET University Grants Commission Qualified 2013 PhD Department of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai Mumbai Teaching experience: 24 years Research experience: 24 years Subjects taught: Language Policy and Politics in India Language Policy and Politics: A comparison of India and Pakistan Public Administration Political Theory Theories of International Relations Indian Constitution Political Thoughts in Maharashtra Western Political Thought Local Self-government (with special reference to Maharashtra) Understanding Politics through Cinema Rights in the context of Maharashtra Dalit Movement in India Regionalism and Regional disparities in Maharashtra 2 Indian Government and Policy Contribution in teaching methods: Chalk and Talk method Assignments Classroom Debates Regular Class Test Visit to Documentation Centers for Screening of Documentaries Presentations Book Reviews Newspaper Clippings Poster Presentation Industrial Visits Participation in conference Evaluation Techniques: Class Test Home Assignments Viva Presentations PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Position Institution Assistant Professor Department of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai: 1. Language Policy and Politics 2. State Politics. Lecturer K. J. Somaiya College of Arts & Commerce, Mumbai: 1. Political Theory, 2. Politics in Maharashtra 3. International Relations. President Marathi Abhyas Kendra (Marathi Study Centre): An organization working for the promotion Marathi language and culture. -

The Khairlanji Murders & India's Hidden Apartheid ANAND

** persistence «• The Khairlanji Murders & India's Hidden Apartheid ANAND TELTUMBDE This book exposes the gangrenous heart of Indian society. ARUNDHATI ROY © Anand Teltumbde's analysis of the public, ritualistic massacre of a dalit family in 21st century India exposes the gangrenous heart of our society. It contextualizes the massacre and describes the manner in which the social, political and state machinery, the police, the mass media and the judiciary all collude to first create the climate for such bestiality, and then cover it up. This is not a book about the last days of relict feudalism, but a book about what modernity means in India. It discusses one of the most important issues in contemporary India. —ARUNDHATI ROY, author of The God of Small Things This book is finally the perfect demonstration that the caste system of India is the best tool to perpetuate divisions among the popular classes to the benefit of the rulers, thus annihilating in fact the efficiency of their struggles against exploitation and oppression. Capitalist modernization is not gradually reducing that reality but on the opposite aggravating its violence. This pattern of modernization permits segments of the peasant shudras to accede to better conditions through the over-exploitation of the dalits. The Indian Left must face this major challenge. It must have the courage to move into struggles for the complete abolition of caste system, no less. This is the prerequisite for the eventual emerging of a united front of the exploited classes, the very first condition for the coming to reality of any authentic popular democratic alternative for social progress. -

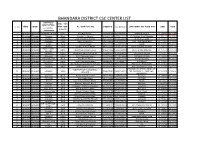

Bhandara District Csc Center List

BHANDARA DISTRICT CSC CENTER LIST ग्रामपंचायत/ झोन / वा셍ड महानगरपाललका Sr. No. जि쥍हा तालुका (फ啍त शहरी कᴂद्र चालक यांचे नाव मोबाईल क्र. CSC-ID/MOL- आपले सरकार सेवा कᴂद्राचा प配ता अ啍ांश रेखांश /नगरपररषद कᴂद्रासाठी) /नगरपंचायत 1 Bhandara Bhandara SHASTRI CHOUK Urban Amit Raju Shahare 9860965355 753215550018 SHASTRI CHOUK 21.177876 79.66254 2 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Avinash D. Admane 8208833108 317634110014 Dr. Mukharji Ward,Bhandara 21.1750113 79.65582 3 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Jyoti Wamanrao Makode 9371134345 762150550019 NEAR UCO BANK 21.174854 79.64352 4 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Sanjiv Gulab Bhure 9595324694 633079050019 CIVIL LINE BHANDARA 21.171533 79.65356 5 Bhandara Bhandara paladi Rural Gulshan Gupta 9423414199 622140700017 paladi 21.169466 79.66144 6 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban SUJEET N MATURKAR 9970770298 712332740018 RAJIV GANDHI SQUARE 21.1694655 79.66144 RAJIV GANDI 7 Bhandara Bhandara Urban Basant Shivshankar Bisen 9325277936 637272780014 RAJIV GANDI SQUARE 21.167537 79.65599 SQUARE 8 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Mohd Wasi Mohd Rafi Sheikh 8830643611 162419790010 RAJENDRA NAGAR 21.16685 79.655364) 9 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Kartik Gyaniwant Akare 9326974400 311156120014 IN FRONT OF NH6 21.166096 79.66028 10 Bhandara Bhandara Tekepar[kormbi] Rural Anita Eknath Bhure 9923719175 217736610016 Tekepar[kormbi] 21.1642922 79.65682 11 Bhandara Bhandara BHANDARA Urban Priya Pritamlal Kumbhare 9049025237 114534420013 BHANDARA 21.162895 79.64346 12 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Md. Sarfaraz Nawaz Md Shrif Sheikh 8484860484 365824810010 POHA GALI,BHANDARA 21.162768 79.65609 13 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Nitesh Natthuji Parate 9579539546 150353710012 Near Bhandara Bus Stop 21.161485 79.65576 FRIENDLY INTERNET ZONE, Z.P TARKESHWAR WASANTRAO 14 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban 9822359897 434443140013 SQ. -

Khairlanji Killings: Bombay HC Commutes Death Sentence of 6 Convicts to Life Term -

Khairlanji killings: Bombay HC commutes death sentence of 6 convicts to life term - ... Side 1 af 1 Printed from Khairlanji killings: Bombay HC commutes death sentence of 6 convicts to life term TIMES NEWS NETWORK & AGENCIES, Jul 14, 2010, 11.14am IST NEW DELHI: The Nagpur bench of Bombay high court on Wednesday commuted death sentence of 6 convicts in the gruesome Khairlanji Dalit family massacre case of 2006 to life imprisonment. The life imprisonment to the accused will be for a period of 25 years, including the time they have already served in prison. A division bench comprising Justices A P Lawande and R C Chauhan pronounced the much-awaited final verdict in the case, turning down a plea by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) challenging the lower court's ruling giving life to two of the eight accused while sentencing to death six people. The judgement was delivered via video conferencing as one of the judges of the division bench Justice Ravindra Chavan is posted at Mumbai. Earlier, Bhandara sessions court had awarded capital punishment to 6 accused and lifer to 2. Those given death were Shatrughana Dhande, Vishwanath Dhande, Ramu Dhande, Sakru Binjewar, Jagdish Mandlekar and Prabhkar Mandlekar. The trial court had given life term to Shishupal Dhande and Gopal Binjewar. Three more accused were acquitted. The horrific incident unfolded on the evening of September 29, 2006, when a group of villagers descended on the Bhotmange family in Khairlanji village in Maharashtra's Bhandara district, IANS reported. They dragged out Surekha Bhaiyyalal Bhotmange, 44, her sons Roshan, 23, Sudhir, 21 and daughter Priyanka, 18, assaulted them brutally, paraded them naked in the village, sexually abused them with sticks and then hacked them to death. -

Understanding Sexual Violence As a Form of Caste Violence

Understanding sexual violence as a form of caste violence Prachi Patil Jawaharlal Nehru University Abstract The paper attempts to understand narratives of sexual violence anchored within the dynamics of social location of caste and gender. Apparent caste-patriarchy and gender hierarchies which are at play in cases of sexual violence against lower-caste and dalit women speak about differential experiences of rape and sexual abuse that women have in India. The paper endeavours to establish that sexual violence is also a form of caste violence by rereading the unfortunate cases of Bhanwari Devi, Khairlanji, Lalasa Devi and Delta Meghwal Keywords: caste-patriarchy, Dalit women, POA Act, rape, sexual violence The caste system has always been the spine of Indian social stratification. It continues to shape the everyday life of the majority of Indians. Caste rules and norms not only colour the daily functioning of village life, but they have also successfully penetrated into modern day life. The Indian caste system classifies individuals in descending order of hierarchy into four mutually exclusive varnas –the Brahmins (priests), the Kshatriyas (warriors), the Vaishyas (merchants) and the Shudras (servants), beyond these four castes is the fifth caste of the Ati- Shudras or the achhoots (untouchables). The formerly untouchable castes are also known as Dalits1. Jodhka (2012) notes that these four or five categories occupied different positions in the status hierarchy, with the Brahmans at the top, followed by the other three varnas in the order mentioned above, with the achhoots occupying a position at the very bottom. Membership into these castes is solely based on the accidental factor of birth. -

In the High Court of Judicature at Bombay, Nagpur Bench, Nagpur

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY, NAGPUR BENCH, NAGPUR. Criminal Confirmation Case No. 4/2008. Central Bureau of Investigation (Through D.S.P.,C.B.I.S.C.B. Chennai) Camp at Bhandara. ¼..Appellant. .versus. 1. Sakru Mahagu Binjewar (Original Accused No.2) 2. Shatrughna Isram Dhande (Original Accused No. 3) 3. Vishwanath Hagru Dhande (Original Accused No. 6) 4. Ramu Mangru Dhande (Original Accused No. 7) 5. Jagdish Ratan Mandlekar (Original Accused No. 8) 6. Prabhakar Jaswant Mandlekar (Original Accused No. 9) Respondent Nos. 1 to 6 R/o: Khairlanji District: Bhandara (Maharashtra State). ...Respondents BombayMr. Ejaz Khan, Spl. P.P. ForHigh appellant. Court Mr. Sudip Jaiswal, Advocate for respondent nos. 1,5 and 6. Mr. N.S.Khandewale, Advocate for respondent nos. 2,3 and 4. ::: Downloaded on - 12/09/2013 11:54:42 ::: 2 Criminal Appeal No. 748/2008 1. Shatrughna s/o Isram Dhande Aged about 40 years. Occupation: Agricultural Labourer. (Original accused no. 3) 2. Vishwanath s/o Hagru Dhande Aged 55 years. Occupation: Agricultural Labourer. (Original accused no. 6) 3. Ramu s/o Mangru Dhande Aged 42 years. Occupation; Agricultural Labourer. (Original accused no.7) 4. Shishupal s/o Vishwanath Dhande, aged 20 years. Occupation: Agricultural Labourer. (Original accused no. 11) (All the appellants are R/o: Village Khairlanji, Tah. Mohadi, Distr.Bhandara.) ¼....Appellants. .versus. The Central Bureau of Investigation, through its Dy.S.P., C.B.I., S.C.B., Chennai, Camp at Bhandara. Bombay High¼....Respondent. Court Mr. N.S.Khandewale Advocate for the appellants. Mr. Ejaz Khan, Spl. -

FACT FINDING REPORT Khairlanji Massacre

FACT FINDING REPORT Khairlanji Massacre: A collection of reports A VJAS Press release Kherlanji Buddhist family Massacred Small village in Bhandara district in Maharashtra has been focus of attention when four member of one dalit family was slaughtered on 29th September 29th, 2006 in bhandara district. Victims are Bhaiyyalal Bhotmange’s wife surekha, 44, his daughter priyanka, 18, sons, roshan, 23, and sudhir, 21.The fact finding team of vidarbha Jan Andolan Samiti visited on 6th October to village kherlanji to know the details of this barbaric killing and they were shocked to learn that , Bhaiyyalal`s wife surekha, 44, his daughter priyanka, 18, sons, roshan, 23, and sudhir, 21, were first stripped naked, dragged from their hut to the choupal 500 meters away and hacked to death by the entire village of the so called upper-castes. vJAS has moved with the fact finding committee report to national human rights commission(nhrc) for independent probe of this dalit massacred as all political parties and local administration are covering up the matter as till date no mla or mp from bhandara has visited the village or Bhaiyyalal, more than a week after the gruesome killing took place. Two mlas from Nagpur, ostensibly sent by the congress higher-ups, visited kherlanji, but did not make any noise. The police are not acting fast and the only two prime witnesses are under threat. Not a single villager’s statement has been recorded. Neighboring villages are living with fear and terror, especially the minority lower castes dalit to dared to demand the right of land were slaughtered in order to give other dalit in villages of Mowadi taluka of bhandara district . -

Snakes of Bhandara District, Maharashtra

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANSIRCF REPTILES • VOL15, &NO AMPHIBIANS 4 • DEC 2008 189 • 27(1):10–17 • APR 2020 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES Snakes. Chasing Bullsnakes of (PituophisBhandara catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: District, Maharashtra, On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 Central. The Shared India History of Treeboas (Coralluswith grenadensis ) Notesand Humans on Grenada: on Natural History A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 1 2 3 4 RESEARCHRahul V. Deshmukh ARTICLES, Sagar A. Deshmukh , Swapnil A. Badhekar , and Roshan Y. Naitame . The1 H.N.Texas Horned 26, Teacher Lizard inColony, Central andKalmeshwar, Western Texas Nagpur, ....................... Maharashtra-441501, Emily Henry, Jason Brewer,India ([email protected]) Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The2Behind Knight Potdar Anole (NursingAnolis equestris Home) in FloridaKalmeshwar, Nagpur, Maharashtra-441501, India ([email protected]) 3TiwaskarWadi ............................................. near BoudhaVihar,Brian Hingana J. Camposano, Raipur, Kenneth Nagpur, L. Krysko, Maharashtra-441110, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. India Donlan, ([email protected]) and Michael Granatosky 212 4 CONSERVATIONAdyal, ALERT Pavani, -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 2 | 2008 the ‘Righteous Anger’ of the Powerlessinvestigating Dalit Outrage Over Caste

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 2 | 2008 ‘Outraged Communities’ The ‘Righteous Anger’ of the Powerless Investigating Dalit Outrage over Caste Violence Nicolas Jaoul Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/1892 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.1892 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Nicolas Jaoul, « The ‘Righteous Anger’ of the Powerless Investigating Dalit Outrage over Caste Violence », South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], 2 | 2008, Online since 31 December 2008, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/samaj/1892 ; DOI : 10.4000/samaj.1892 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The ‘Righteous Anger’ of the PowerlessInvestigating Dalit Outrage over Caste ... 1 The ‘Righteous Anger’ of the Powerless Investigating Dalit Outrage over Caste Violence Nicolas Jaoul Introduction1 1 In November 2006, the Maharashtrian Buddhist community2 revolted against the massacre of four members of a family by the dominant castes in Khairlanji village of the Vidarbha region (Eastern Maharashtra), more exactly against the inaction or alleged compliance of the local administration. The massacre highlighted the enormous difference between the notion of a democratic society and the actual suppression of poor and marginalised Dalits (‘untouchables’). Official neglect of Dalits, as well as the routine failure to apply the specific law meant to prevent Dalit atrocities, makes possible the occurrence of such atrocities in broad daylight. As is generally the case with violent attacks on rural Dalits, the murderers not only wanted to teach assertive Dalits a lesson, but also to flaunt how openly they could afford to do it.