At Derby Hill, New York a White-Tailed Eagle(Haliaeetus Albicilla)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Status of Birds of Prey and Owls in Norway

Conservation status of birds of prey and owls in Norway Oddvar Heggøy & Ingar Jostein Øien Norsk Ornitologisk Forening 2014 NOF-BirdLife Norway – Report 1-2014 © NOF-BirdLife Norway E-mail: [email protected] Publication type: Digital document (pdf)/75 printed copies January 2014 Front cover: Boreal owl at breeding site in Nord-Trøndelag. © Ingar Jostein Øien Editor: Ingar Jostein Øien Recommended citation: Heggøy, O. & Øien, I. J. (2014) Conservation status of birds of prey and owls in Norway. NOF/BirdLife Norway - Report 1-2014. 129 pp. ISSN: 0805-4932 ISBN: 978-82-78-52092-5 Some amendments and addenda have been made to this PDF document compared to the 75 printed copies: Page 25: Picture of snowy owl and photo caption added Page 27: Picture of white-tailed eagle and photo caption added Page 36: Picture of eagle owl and photo caption added Page 58: Table 4 - hen harrier - “Total population” corrected from 26-147 pairs to 26-137 pairs Page 60: Table 5 - northern goshawk –“Total population” corrected from 1434 – 2036 pairs to 1405 – 2036 pairs Page 80: Table 8 - Eurasian hobby - “Total population” corrected from 119-190 pairs to 142-190 pairs Page 85: Table 10 - peregrine falcon – Population estimate for Hedmark corrected from 6-7 pairs to 12-13 pairs and “Total population” corrected from 700-1017 pairs to 707-1023 pairs Page 78: Photo caption changed Page 87: Last paragraph under “Relevant studies” added. Table text increased NOF-BirdLife Norway – Report 1-2014 NOF-BirdLife Norway – Report 1-2014 SUMMARY Many of the migratory birds of prey species in the African-Eurasian region have undergone rapid long-term declines in recent years. -

Introduction

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

A Multi-Gene Phylogeny of Aquiline Eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) Reveals Extensive Paraphyly at the Genus Level

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com MOLECULAR SCIENCE•NCE /W\/Q^DIRI DIRECT® PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION ELSEVIER Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35 (2005) 147-164 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-gene phylogeny of aquiline eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) reveals extensive paraphyly at the genus level Andreas J. Helbig'^*, Annett Kocum'^, Ingrid Seibold^, Michael J. Braun^ '^ Institute of Zoology, University of Greifswald, Vogelwarte Hiddensee, D-18565 Kloster, Germany Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD 20746, USA Received 19 March 2004; revised 21 September 2004 Available online 24 December 2004 Abstract The phylogeny of the tribe Aquilini (eagles with fully feathered tarsi) was investigated using 4.2 kb of DNA sequence of one mito- chondrial (cyt b) and three nuclear loci (RAG-1 coding region, LDH intron 3, and adenylate-kinase intron 5). Phylogenetic signal was highly congruent and complementary between mtDNA and nuclear genes. In addition to single-nucleotide variation, shared deletions in nuclear introns supported one basal and two peripheral clades within the Aquilini. Monophyly of the Aquilini relative to other birds of prey was confirmed. However, all polytypic genera within the tribe, Spizaetus, Aquila, Hieraaetus, turned out to be non-monophyletic. Old World Spizaetus and Stephanoaetus together appear to be the sister group of the rest of the Aquilini. Spiza- stur melanoleucus and Oroaetus isidori axe nested among the New World Spizaetus species and should be merged with that genus. The Old World 'Spizaetus' species should be assigned to the genus Nisaetus (Hodgson, 1836). The sister species of the two spotted eagles (Aquila clanga and Aquila pomarina) is the African Long-crested Eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis). -

Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members. -

Review of Illegal Killing and Taking of Birds in Northern and Central Europe and the Caucasus

Review of illegal killing and taking of birds in Northern and Central Europe and the Caucasus Overview of main outputs of the project The information collated and analysed during this project has been summarised in a variety of outputs: 1. This full report Presenting all the aspects of the project at regional and national levels http://www.birdlife.org/illegal-killing 2. Scientific paper Presenting results of the regional assessment of scope and scale of illegal killing and taking of birds in Northern and Central Europe and the Caucasus1 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bird-conservation-international 3. Legislation country factsheets Presenting a review of national legislation on hunting, trapping and trading of birds in each assessed country http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/country (under ‘resources’ tab) 4. ‘The Killing 2.0’ Layman’s report Short communications publication for publicity purposes with some key headlines of the results of the project and the previous one focussing on the Mediterranean region http://www.birdlife.org/illegal-killing Credits of front cover pictures 1 2 3 4 1 Hen harrier Circus cyaneus © RSPB 2 Illegal trapping of Hen Harrier in the UK © RSPB 3 Common Coot (Fulica atra) © MISIK 4 Illegal trade of waterbirds illegally killed in Azerbaijan © AOS Citation of the report BirdLife International (2017) Review of illegal killing and taking of birds in Northern and Central Europe and the Caucasus. Cambridge, UK: BirdLife International. 1 Paper in revision process for publication in Bird Conservation International in October 2017 when this report is released 1 Executive Summary The illegal killing and taking of wild birds remains a major threat on a global scale. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

Alectoris Chukar

PEST RISK ASSESSMENT Chukar partridge Alectoris chukar (Photo: courtesy of Olaf Oliviero Riemer. Image from Wikimedia Commons under a Creative Commons Attribution License, Version 3.) March 2011 This publication should be cited as: Latitude 42 (2011) Pest Risk Assessment: Chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar). Latitude 42 Environmental Consultants Pty Ltd. Hobart, Tasmania. About this Pest Risk Assessment This pest risk assessment is developed in accordance with the Policy and Procedures for the Import, Movement and Keeping of Vertebrate Wildlife in Tasmania (DPIPWE 2011). The policy and procedures set out conditions and restrictions for the importation of controlled animals pursuant to s32 of the Nature Conservation Act 2002. For more information about this Pest Risk Assessment, please contact: Wildlife Management Branch Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Address: GPO Box 44, Hobart, TAS. 7001, Australia. Phone: 1300 386 550 Email: [email protected] Visit: www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au Disclaimer The information provided in this Pest Risk Assessment is provided in good faith. The Crown, its officers, employees and agents do not accept liability however arising, including liability for negligence, for any loss resulting from the use of or reliance upon the information in this Pest Risk Assessment and/or reliance on its availability at any time. Pest Risk Assessment: Chukar partridge Alectoris chukar 2/20 1. Summary The chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar) is native to the mountainous regions of Asia, Western Europe and the Middle East (Robinson 2007, Wikipedia 2009). Its natural range includes Turkey, the Mediterranean islands, Iran and east through Russia and China and south into Pakistan and Nepal (Cowell 2008). -

Conservation Genetics of the White-Tailed Eagle

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 190 Conservation Genetics of the White-Tailed Eagle FRANK HAILER ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 UPPSALA ISBN 91-554-6581-1 2006 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-6911 !""# $ % & ' ( & & )' '* +' , ('* - .* !""#* / & ' ' 0+ (* 1 * 2"* %3 * * 456 2 0%%70#%8 0 * +' ,' 0 ( & ' ' & (' , 9* +' ' ( ' & ( ( ' ( ( ' & ' ,' 0 (* . 9 , & ' ,' 0 (* 1 ' ,' 0 ( ( ' & * +' ' : & ,' ( ' ( ' ( * ,' 0 ( , ( ' !" ' * +' ' ' , ' 9 ' ( & & ( * / & , , ( & ' ' ( ( ( * 4 ' ( ( & ,' 0 ( ' && ( & ( * 1 & ( ' & ' & ' ( 6 , * ' 61 & ,' 0 ( , , ' , * +' 9 4 1( &( ( & ( & ( ' ( & * , * ; , ' ' , 4 / *+' & && ( ' , 9 9 ( & ' * && , , ' < ( & , = & ( & , * - 61 ( 9 ' ( ( ' ! " # " $ " # % " & '( )*" " #+,-./0 " > . 9 - !""# 4556 #% 0#! 7 456 2 0%%70#%8 0 $ $$$ 0#2 ?' $@@ *9*@ A B $ $$$ 0#2 C to my parents, and my sister and brother Colour artwork on front page kindly provided by Anna Widén. List of papers The thesis is based on the following papers, hereafter referred to -

![Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0282/ciconiiformes-charadriiformes-coraciiformes-and-passeriformes-1100282.webp)

Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.]

Die Vogelwarte 39, 1997: 131-140 Clues to the Migratory Routes of the Eastern Fly way of the Western Palearctics - Ringing Recoveries at Eilat, Israel [I - Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.] By Reuven Yosef Abstract: R euven , Y. (1997): Clues to the Migratory Routes of the Eastern Fly way of the Western Palearctics - Ringing Recoveries at Eilat, Israel [I - Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.] Vogelwarte 39: 131-140. Eilat, located in front of (in autumn) or behind (in spring) the Sinai and Sahara desert crossings, is central to the biannual migration of Eurasian birds. A total of 113 birds of 21 species ringed in Europe were recovered either at Eilat (44 birds of 12 species) or were ringed in Eilat and recovered outside Israel (69 birds of 16 spe cies). The most common species recovered are Lesser Whitethroat {Sylvia curruca), White Stork (Ciconia cico- nia), Chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita), Swallow {Hirundo rustica) Blackcap (S. atricapilla), Pied Wagtail {Motacilla alba) and Sand Martin {Riparia riparia). The importance of Eilat as a central point on the migratory route is substantiated by the fact that although the number of ringing stations in eastern Europe and Africa are limited, and non-existent in Asia, several tens of birds have been recovered in the past four decades. This also stresses the importance of taking a continental perspective to future conservation efforts. Key words: ringing, recoveries, Eilat, Eurasia, Africa. Address: International Bird Center, P. O. Box 774, Eilat 88106, Israel. 1. Introduction Israel is the only land brigde between three continents and a junction for birds migrating south be tween Europe and Asia to Africa in autumn and north to their breeding grounds in spring (Yom-Tov 1988). -

Spring 1994 Raptor Migration at Eilat, Israel

J RaptorRes. 29(2):127-134 ¸ 1995 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. SPRING 1994 RAPTOR MIGRATION AT ElLAT, ISRAEL REUVEN YOSEF International Birding Center, P.O. Box 774, Eilat 88000, Israel ABSTRACT.--Inthe Old World, most raptors and other soaring birds breed north of 35øN latitude and winter between30øN and 30øS.An estimated3 000 000 raptors from Europe and Asia migrate through the Middle East. Israel is the only land bridge for birds migrating south between Europe and Asia to Africa in autumn, and north to their breedinggrounds in spring. In spring 1994 a total of 1 031 387 soaringbirds were countedin 92 d of observation.Of these 1 022 098 were raptors of 30 species,for an averageof 11 110 raptors per day. The most abundant specieswere the honey buzzard (Pernisapivorus) and the steppebuzzard (Buteobuteo vulpinus). Levant sparrowhawks(Accipiter brevipes), steppe eagles (Aquilanipalensis), and black kites (Milvus rnigrans)numbers were smallerby an order of magnitude.A total of 1999 raptorswere unidentifiedto species(0.19% of total). KEY WORDS: Eilat; Israel;migration; raptors; spring 1994;survey. Migraci6n de rapacesen la primaverade 1994 en Eilat, Israel RESUMEN.--Enel viejomundo, la mayorlade las rapacesy otrasaves planeadoras nidifican al norte de los 35øN,yen invierno se encuentranentre los 30øN y 30øS.Se ha estimadoen tres millonesde rapaces de Europa y Asia que migran a travis del Medio Este. Israel es solamenteel puentede tierra para aves que migran a Africa desdeEuropa y Asia durante el otofio, y al norte durante la primavera hacia sus fireasreproductivas. En la primaverade 1994 un total de 1 031 387 de avesfueron contadas en 92 dias de observaci6n.De elias,1 022 098 fueronrapaces de 30 especies,i.e., conun promediode 11 110 rapaces pot dla. -

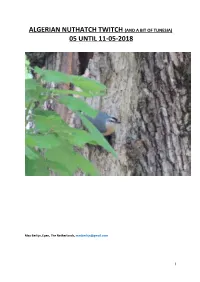

Algerian Nuthatch Twitch (And a Bit of Tunesia) 05 Until 11-05-2018

ALGERIAN NUTHATCH TWITCH (AND A BIT OF TUNESIA) 05 UNTIL 11-05-2018 Max Berlijn, Epen, The Netherlands, [email protected] 1 Legenda: *AAAA = New (Holarctic) Species (2) AAAAA = Good species for the trip or for me (because not often seen) The list order is conformed the WP checklist with the recent changes on the splitting and lumping issue mainly based on publications in the “important magazines”. Subspecies is only mentioned when thought to be important and really visible in the field. The totals of birds per species are just a total of the birds I saw to give an idea how many of a species you encounter during a trip. Only species seen are mentioned, and heard when no lifer. On this trip the weather was good with no rain, mostly sunny with (dry) temperatures just above the 20 C and often no wind accept on the first day at Cap Bon. Cap Bon on a very windy day The breeding site of the first visited pair of Algerian Nuthatches Itinerary 05-05 Flew from Frankfurt to Tunis and met the group and the local guide Mohamed Ali Dakhli (+21621817717, [email protected] ) around 18.00 hours and drove to Cap Bon. 06-05 Birded around El Haouaria and Cap Bon all day. There was a very strong NW wind force 7. 07-05 Birded again around El Haouaria, with a three our pelagic from the cape. Later that day we drove to Tabarka near the Algerian border. Here we handed in our bins. 08-05 Drove from Tabarka to Jijel in Algeria. -

Tunisia 4Th - 9 Th February 2007

Tunisia 4th - 9 th February 2007 Marbled Duck and El Jem Colleseum by Adam Riley Trip Report compiled by Tour Leaders Erik Forsyth & David Hoddinott Tour summary On the first day of the tour we headed off to a wetland situated on the outskirts of Tunis. This proved to be very productive and our bird-list started in earnest with Eared Grebe, Greater Flamingo, Eurasian Golden Plover and the attractive “pink flushed” Slender-billed Gull. Our next stop was the ruins at Carthage and while taking in the history from our local guide we still managed a few excellent birds including European Goldfinch, Dartford and Sardinian Warbler, a sunbathing Eurasian Wryneck and several Black Redstarts. The best find however was a Hedge Accentor or Dunnock found by Mark. This is a scarce winter visitor to North Africa. After leaving Tunis we soon arrived at Mt Zaghouan, famous for the spring that supplied ancient Carthage with its entire water supply nearly 70km away. Highlights here were a pair of Lanner Falcon, Peregrine Falcon, Blue Rock Thrush and close views of several Red Crossbill. Arriving at Sidi Jedidi in the afternoon we quickly found our target bird: the rare and threatened White-headed Duck. Good scope views were enjoyed of this attractive duck and a bonus was brief views of a Water Rail running through the reedbed. En route, a flock of sixty Common Crane were seen. We finally arrived in Mahres after dark and sat down to a welcome meal after a full day of birding and antiquities. A great way to start the tour! Rockjumper Birding Tours Trip Report Tunisia February 2007 2 Today we had an early start for a visit to the Bou Hedma NP.