Teaching Harlem Students in a College Readiness Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1961-1962. Bulletin and College Roster. Hope College

Hope College Digital Commons @ Hope College Hope College Catalogs Hope College Publications 1961 1961-1962. Bulletin and College Roster. Hope College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.hope.edu/catalogs Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Hope College, "1961-1962. Bulletin and College Roster." (1961). Hope College Catalogs. 130. http://digitalcommons.hope.edu/catalogs/130 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Hope College Publications at Digital Commons @ Hope College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hope College Catalogs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Hope College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOPE COLLEGE BULLETIN COLLEGE ROSTER TABLE OF CONTENTS C O L L E G E R O S T E R page The College Staff - Fall 1961 2 Administration 2 Faculty 4 The Student Body - Fall 1961 7 Seniors 7 Juniors 9 Sophomores 12 Freshmen 16 Special Students 19 Summer School Students - Fall 1961 21 Hope College Campus 21 Vienna Campus 23 COLLEGE DIRECTORY Fall 1961 (Home and college address and phone numbers) The College Staff 25 Students 29 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Library Information 58 Health Service 59 College Residences 60 College Telephones 61 NEW STAFF MEMBERS-SECOND SEMESTER Name Home Address College Address Phone Coates, Mary 110 E. 10th St. Durfee Hall EX 6-7822 Drew, Charles 50 E. Central Ave., Zeeland P R 2-2938 Fried, Paul 18 W. 12th St. Van Raalte 308 E X 6-5546 Loveless, Barbara 187 E. 35th St. E X 6-5448 Miller, James 1185 E. -

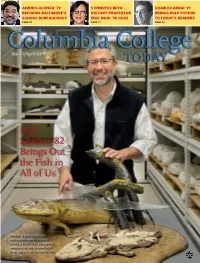

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

1946-Resumes-After-L

Columbia Spectator VOL. LXIX - No. 29. TUESDAY, MARCH 5, 1946. PRICE: FIVE CENTS Success is New SA Head Approved CSPA Draws Petitions Due Thursday Churchill at By Emergency Council School For NROTC Elections 'Club '49; Frank E. Karelsen Ill's resig- High Petitions of candidates for Columbia nation as Chairman of the Stu- Navy representative on the Emergency Council due by dent Administrative Executive Journalists are Expectation noon Thursday, it was announced March 18 election of Frank Council and the 2800 Editors Attend by Fred Kleeberg, chairman of College Kings, Broadway laquinta as his successor were the Elections Commission. Pe- Wartime British Leader confirmed by the Emergency Scholastic Press Group titions may be handed in at the Stars at Hop Saturday; Council last Thursday. Karelsen, King's Crown Office, 405 John To Receive Honorary Invited two term SAAC Chairman, ex- Gathering 21-23 March Jay Hall, or may be handed to Degree at Low Library All Undergrads plained that his decision to re- Kleeberg personally. sign had resulted from his On March 21, 22, and 23, some Plans for one of the most novel Actual elections will take place Winston Churchill, war-tim e "pressing duties" as a newly 2,800 school editors and advisors, and original of social affairs ever on Monday, March 11, in leader of the British people, will elected Emergency Council mem- be presented at Columbia been representing schools from all parts Hartley lobby from noon to one. visit Columbia University on Mon- to ber. However, he expressed con- completed, it was revealed, last of the country, will gather at Col- An officer of the battalion of- day afternoon, March 18, to re- fidence in laquinta who had night by the committee in charge umbia to attend the 22nd annual fice staff will be preent at the ceive from Dr. -

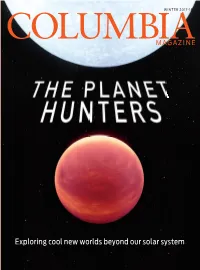

Exploring Cool New Worlds Beyond Our Solar System

WINTER 2017-18 COLUMBIA MAGAZINE COLUMBIA COLUMBIAMAGAZINE WINTER 2017-18 Exploring cool new worlds beyond our solar system 4.17_Cover_FINAL.indd 1 11/13/17 12:42 PM JOIN THE CLUB Since 1901, the Columbia University Club of New York has been a social, intellectual, cultural, recreational, and professional center of activity for alumni of the eighteen schools and divisions of Columbia University, Barnard College, Teachers College, and affiliate schools. ENGAGE IN THE LEGACY OF ALUMNI FELLOWSHIP BECOME A MEMBER TODAY DAVE WHEELER DAVE www.columbiaclub.org Columbia4.17_Contents_FINAL.indd Mag_Nov_2017_final.indd 1 1 11/15/1711/2/17 12:463:13 PM PM WINTER 2017-18 PAGE 28 CONTENTS FEATURES 14 BRAVE NEW WORLDS By Bill Retherford ’14JRN Columbia astronomers are going beyond our solar system to understand exoplanets, fi nd exomoons, and explore all sorts of surreal estate 22 NURSES FIRST By Paul Hond How three women in New York are improving health care in Liberia with one simple but e ective strategy 28 JOIN THE CLUB LETTER HEAD By Paul Hond Scrabble prodigy Mack Meller Since 1901, the Columbia University Club of minds his Ps and Qs, catches a few Zs, and is never at a loss for words New York has been a social, intellectual, cultural, recreational, and professional center of activity for 32 CONFESSIONS alumni of the eighteen schools and divisions of OF A RELUCTANT REVOLUTIONARY Columbia University, Barnard College, By Phillip Lopate ’64CC Teachers College, and affiliate schools. During the campus protests of 1968, the author joined an alumni group supporting the student radicals ENGAGE IN THE LEGACY OF ALUMNI FELLOWSHIP 38 FARSIGHTED FORECASTS By David J. -

Chronology of Events

CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS ll quotes are from Spectator, Columbia’s student-run newspaper, unless otherwise specifed. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia A .edu/. Some details that follow are from Up Against the Ivy Wall, edited by Jerry Avorn et al. (New York: Atheneum, 1969). SEPTEMBER 1966 “After a delay of nearly seven years, the new Columbia Community Gymnasium in Morningside Park is due to become a reality. Ground- breaking ceremonies for the $9 million edifice will be held early next month.” Two weeks later it is reported that there is a delay “until early 1967.” OCTOBER 1966 Tenants in a Columbia-owned residence organize “to protest living condi- tions in the building.” One resident “charged yesterday that there had been no hot water and no steam ‘for some weeks.’ She said, too, that Columbia had ofered tenants $50 to $75 to relocate.” A new student magazine—“a forum for the war on Vietnam”—is pub- lished. Te frst issue of Gadfy, edited by Paul Rockwell, “will concentrate on the convictions of three servicemen who refused to go to Vietnam.” This content downloaded from 129.236.209.133 on Tue, 10 Apr 2018 20:25:33 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms LII CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS Te Columbia chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) orga- nizes a series of workshops “to analyze and change the social injustices which it feels exist in American society,” while the Independent Commit- tee on Vietnam, another student group, votes “to expand and intensify its dissent against the war in Vietnam.” A collection of Columbia faculty, led by Professor Immanuel Wallerstein, form the Faculty Civil Rights Group “to study the prospects for the advancement of civil rights in the nation in the coming years.” NOVEMBER 1966 Columbia Chaplain John Cannon and ffeen undergraduates, including Ted Kaptchuk, embark upon a three-day fast in protest against the war in Vietnam. -

Contents This Year’S Commencement Week Was an Enormous Success, Due to the Outstanding Effort and Professionalism of Many of Our Employees

COMMENCEMENT 2008 News for the Employees of Columbia University Facilities VOLUME 5 | SUMMER 2008 Contents This year’s Commencement Week was an enormous success, due to the outstanding effort and professionalism of many of our employees. Our hard work was visually apparent – the campus looked great and we seamlessly handled over 150 separate events, including an unforgettable Commencement Day that included over 20,000 2 Customer Compliments participants and guests and 11,647 degree candidates. Read more on page 8. 3 From the Executive Vice President 4 2008 Summer Construction Activity CUF MECHANIC SAVES LIFE 5 Awards 6 How We LEED 8 2008 Commencement 9 Our Eyes & Ears 10 Welcome & Congratulations 11 Employee Profi le: Veeramuthu “Kali” Kalimuthu 12 The Back Page CUF Assistant Mechanic and NYC subway hero Veeramuthu”Kali” Kalimuthu was honored at City Hall for his brave and heroic actions. Read more on page 11. Customer Compliments Dear [Matt] Early, Dear Anthony [Nasser], I have had the pleasure of working for Columbia University for 16 years Today one of our students was in crisis and demonstrated some rather and during my time here, I have worked alongside many individuals, worrying behavior while at Lenfest (she does not live in the building). whom represent many departments. But in all the years of working The attendant on duty this evening, Orlando, was incredibly helpful. He directly with your department, I have never seen its leader practice, in not only contacted Public Safety, which was of course the appropriate true form, a model of collective collaboration, until you came along. -

Previous Old Masters 1950-2016

Previous Old Masters 1950-2016 2016 Old Masters Dr. Phoebe Lydia Bailey – Former Consultant/Corporate Coach for Vision in Action and National Director of Educational Foundations and Academic Innovations for the Boys & Girls Clubs of America William Bindley – Founded Bindley Western Industries, Chairman of Guardian Pharmacy, former owner of the Indiana Pacers Professional Basketball Team Terry Cross – Current Board Director on the Coast Guard Auxiliary Association Foundation Board, served as the 24th Vice Commandant of the United States Coast Guard, Coast Guard’s second in command, Agency Acquisition Executive Michael Klipsch – Former President, Chief Operating Officer, and Chief Counsel for Klipsch Group, Inc., Co-Founder, President and CEO, of Klipsch-Card Athletic Facilities. Peter Kraemer – Current Chief Supply Officer of Anheuser-Busch InBev, Former Chairman of the American Malting and Barely Association, Fifth-Generation Brewmaster Dr. Charles Owubah – Vice President for the Evidence and Learning Unit of World Vision International Lesley Sarkesian – Southwest Region Executive at Vistage International, Former Senior Vice President and Client Managing Director at Xerox, Founder & CEO of Sarkesian Ventures LLC, and Chaos CocktailsÒ Dr. Belinda Seto – Deputy Director of the National Eye Institute, Editor-in-Chief of the American Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging Ellyn Shook – Chief Leadership and Human Resources Officer at Accenture, Top 10 CHROs by Forbes.com Dr. Jerry White – Author, Scientist, retired US Air Force -

Download This Issue As A

CHRIS KIMBALL ‘73 JONATHAN COLE ‘64 SPECIAL INSERT: COOKS UP RECIPES SAYS UNIVERSITIES ALUMNI REUNION THAT WORK FUEL INNOVATION WEEKEND 2010 PAGE 20 PAGE 26 Columbia College July/August 2010 TODAY Congratulations, Class of 2010! ’ll meet you for a I drink at the club...” Meet. Dine. Play. Take a seat at the newly renovated bar grill or fine dining room. See how membership in the Columbia Club could fit into your life. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 24 16 34 53 8 20 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS PE C IAL NSE R T 2 ETTE R S TO THE LASS OF OINS THE S I : L C 2010 J ALUMNI REUNION EDITO R 16 ANKS OF LUMNI R A WEEKEND 2010 3 Class Day and Commencement marked a rite of Eight pages of photos, WITHIN THE FAMIL Y including class photos, from passage for the Class of 2010. 4 R OUND THE UADS the June celebration. A Q By Ethan Rouen ’04J and Alex Sachare ’71 4 Senior Dinner 5 33 OOKSHELF Van Doren, Trilling Photos by Char Smullyan and Eileen Barroso B Awards Featured: Apostolos Doxiadis 6 ’72’s graphic novel Logicomix: Academic Awards and Prizes An Epic Search for Truth, and 7 FEATURES its hero, Bertrand Russell. Smith To Coach Men’s Basketball 8 35 BITUA R IES “99 Columbians” COOKING 101 O 10 35 5 Minutes with … 20 Chris Kimball ’73, head of the America’s Test Kitchen Arthur S. -

Weather Underground—Things That Happened to Me When I Was a Kid

William Morrow An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Mark Rudd My Life with SDS and the Weathermen Contents Preface vi PART I: COLUMBIA (1965–1968) 1 A Good German 3 2 Love and War 27 3 Action Faction 38 4 Columbia Liberated 57 5 Police Riot: Strike! 85 6 Create Two, Three, Many Columbias 104 PART II: SDS AND WEATHERMAN (1968–1970) 7 National Traveler 119 8 SDS Split 141 9 Bring the War Home! 154 10 Days of Rage 171 Photographic Insert v | CONTENTS 11 To West Eleventh Street 187 12 Mendocino 204 PART III: UNDERGROUND (1970–1977) 13 The Bell Jar 219 14 Santa Fe 233 15 Schoolhouse Blues 250 16 WUO Split 270 17 A Middle-Class Hero 285 Epilogue 301 Acknowledgments 323 Appendix: Map of Columbia University Main Campus, New York City, 1968 325 About the Author Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Preface or twenty-five years I’d avoided talking about my past. During that time I had made an entirely new life in Albu- Fquerque, New Mexico, as a teacher, father of two, inter- mittent husband, and perennial community activist. But in a short few months, two seemingly unrelated events came together to make me change my mind and begin speaking in public about my role in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Weather Underground—things that happened to me when I was a kid. First, in March 2003, the United States attacked Iraq, beginning a bloody, long, and futile war of conquest. What I saw, despite some significant differences, was Vietnam all over again. -

Student Conduct and Community Standards Gender-Based Misconduct Resources for Students

STUDENT CONDUCT AND COMMUNITY STANDARDS GENDER-BASED MISCONDUCT RESOURCES FOR STUDENTS ON-CAMPUS RESOURCES The University Health Services Student Fee covers the on-campus resources that are available to students enrolled in their school’s health service program. Services are available during normal business hours, 9:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m., unless otherwise noted. CONFIDENTIAL Sexual Violence Response & Rape Crisis/Anti-Violence University Counseling and Psychological Services Support Center* ● Morningside: Alfred Lerner Hall, ● Morningside: Alfred Lerner Hall, Suite 700 5th and 8th Floors | 212-854-2878 ● CUIMC: 60 Haven Ave, Bard Hall, Suite 206 ● CUIMC: 100 Haven Ave, Tower 2, 3rd Floor | ● Helpline: 212-854-HELP (4357) (Available 24 hours a 212-305-3400 day year-round) ● Barnard: 100 Hewitt Hall, 1st Floor | 212-854-2092 Ombuds Office After hours 855-622-1903 ● Morningside: 660 Schermerhorn Ext. | 212-854-1234 University Pastoral Counseling ● Manhattanville: 615 West 131st St | 212-854-1234 ● Office of the University Chaplain: (Ordained Clergy) ● CUIMC: 154 Haven Ave, Room 412 |212 -304-7026 Earl Hall Center | 212-854-1493 Medical Services Columbia Office of Disability Services (Confidential ● Morningside: John Jay, 4th Floor | 212-854-7426 | Mon– Resource for Columbia Only) Thur 9am-4:30pm | Fri 8am – 3:30pm ● Morningside: Wien Hall, Suite 108A | 212- 854-2388 ● CUIMC: 100 Haven Ave, Tower 2, 2nd Floor| http://www.health.columbia.edu/disability-services 212-305-3400 Indicates that facility supports Teachers College. ● Barnard: Lower Level Brooks Hall | 212-854-2091 The medical treatment resources listed above can provide treatment for injuries and for potential exposure to sexually transmitted diseases. -

Proposal Selection Poetry Reading for Ofchairman Attempt to Agree on Board Changes W

Columbia Daily Spectator Vol. LXIX 345 WEDNESDAY, MARCH 19, 1947 No. 68 March 21 Set Student Board RejectsPlan's Young As Deadline for Proposal Selection Poetry Reading for ofChairman Attempt to Agree on Board Changes W. H. Auden to Speak; College Student Council Debaters, Yale Terminates in Temporary Stalemate Fifty Dollars Offered To Appoint Committees Student Board started its weekly meeting yesterday To Winner of Contest Columbia University's Stu- To Spar Before dent Council decided at its last with a motion to throw out that feature of the Young Plan Friday, March 21, has been des- meeting to devote the next two which would place the power of election of the Board Chair- ignated as the final deadline for months to the reor- 3 Adjudicators Body Despite Boar's exclusively man with the Student as a whole. the fact all contributions to the ganization of the Council. A Head Poetry sponsored that an overwhelming majority of the voters in last week's Contest, steering committee was appoint- The Clermont Masonic Lodge, Philolexian Society and 'referendum approved the Young- by the ed, and it held a meeting yes- which is sponsoring tomorrow the Columbia Review. A fifty dol- proposals, the motion to retain terday to smooth the way for between Colum- prize, and addition- night's meeting the present system of selection of lar first two the appointment of the various Lowdown al awards of twenty-five dollars bia's Debate Council and Yale, has Will Give a Senior chairman by the Board, committees at the next meeting given the best poems made known the fact that three was unanimously passed after will be to of the Student Council, which faculty judges. -

December 2007

THE UNDERGRADUATE MAGAZINE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY , EST . 1890 Vol. XIV No. IV December 2007 THE WAR ON FUN Prohibition Returns to Morningside Heights By Joseph Meyers FAVORITE SON A Conversation With Playwright Tony Kushner By Lydia DePillis THINKING OUTSIDE THE GODBOX: riverside’s INTERCHURCH CENTER KEEPS THE FAITH ALSO : MAC GENII , KEROUAC , MARGOT AT THE WEDDING Lorum ipsum bla bla bla Editor-in-Chief TAYLOR WALSH Publisher JESSICA COHEN Managing Editor LYDIA DEPILLIS (Bwog) Culture Editor PAUL BARNDT Features Editor ANDREW MCKAY FLYNN Literary Editor HANNAH GOLDFIELD Senior Editors ANNA PHILLIPS KATIE REEDY JULI N. WEINER Layout Editor Editor-at-Large DANIEL D’ADDARIO JAMES R. WILLIAMS Deputy Layout Editor Graphics Editor J. JOSEPH VLASITS ALLISON A. HALFF Web Master Copy Chief ZACHARY VAN SCHOUWEN ALEXANDER STATMAN Staff Writers SUMAIYA AHMED, HILLARY BUSIS, SASHA DE VOGEL, MERRELL HAMBLETON, DAVID ISCOE, KAREN LEUNG, JOSEPH MEYERS, ALEXANDRA MUHLER, MARYAM PARHIZKAR, ARMIN ROSEN, CAROLINE ELIZABETH ROBERTSON, LUCY TANG, SARA VOGEL Artists JULIA BUTAREVA, MAXINE KEYES, JENNY LAM, SHAINA RUBIN, ZOË SLUTZKY, DIANA ZHENG Contributors MAXWELL LEE COHEN, CHRISTOPHER MORRIS-LENT, JUSTIN GONÇALVES, KURT KANAZAWA, KATE LINTHICUM, YELENA SHUSTER, PIERCE STANLEY, LUCY SUN, ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS 2 THE BLUE AND WHITE THE BLUETOPCAP AND TK WHITE Vol. XIV FAMAM EXTENDIMUS FACTIS No. IV COLUMNS 4 BLUEBOOK 8 CAMPUS CHARACTERS 11 VERILY VERITAS 14 DIGITALIA COLUMBIANA 33 MEASURE FOR MEASURE 35 CAMPUS GOSSIP COVER STORY Joseph Meyers 16 THE WAR ON FUN Prohibition returns to Morningside Heights. FEATURES Andrew Flynn 12 THINKING OUTSIDE THE GODBOX Riverside’s Interchurch Center keeps the faith. Juli N. Weiner 20 CULT OF THE GENIUS High noon at the Fifth Avenue Apple Store.