Weather Underground—Things That Happened to Me When I Was a Kid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack!

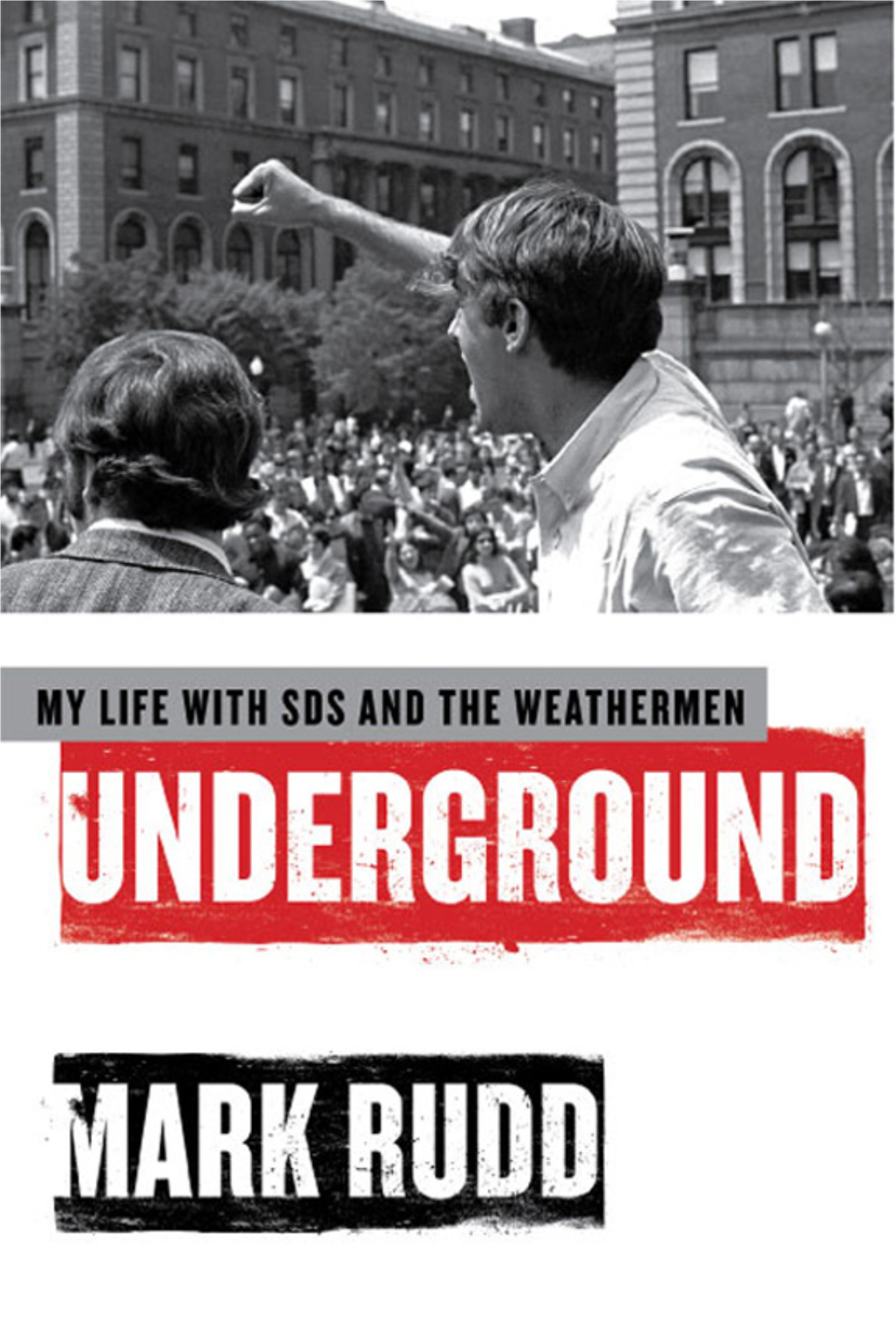

Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack! I attended part of a January 20, 2006, "day workshop of interventions" — aka "a day of dialogic interventions" — at Columbia University on "Radical Politics and the Ethics of Life."[1] The event aimed "to stage a series of encounters . to bring to light . the political aporias [sic] erected by the praxis of urban guerrilla groups" in Europe and the United States from the 1960s to the 80s.[2] Hosted by Columbia's Anthropology Department, workshop speakers included veterans and leaders of the Weather Underground Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers, historian Jeremy Varon, poststructuralist theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and a dozen others. The panel I sat through was just awful.[3] Veterans of Weather (as well as some fans) seem to be on a drive to rehabilitate, cleanse, and perhaps revive it — not necessarily as a new organization, but rather as an ideological component of present and future movements. There have been signs of such a sanitization and romanticization for some time. A landmark in this rehabilitation is Bill Ayers, Fugitive Days: A Memoir (Beacon Press 2001; Penguin Books 2003). This is a dubious account, full of anachronisms, inaccuracies, unacknowledged borrowings from unnamed sources (such as the documentary, Atomic Cafe, 17-19), adding up to an attempt to cover over the fact that Ayers was there only for a part of the things he describes in a volume that nonetheless presents itself as a memoir. It's also faux literary and soft core ("warm and wet and welcoming"(68)), "ruby mouth"(38), "she felt warm and moist"(81)), full of archaic sexism, littered with boasts of Ayers's sexual achievements, utterly untouched by feminism. -

The Hyporheic Handbook a Handbook on the Groundwater–Surface Water Interface and Hyporheic Zone for Environment Managers

The Hyporheic Handbook A handbook on the groundwater–surface water interface and hyporheic zone for environment managers Integrated catchment science programme Science report: SC050070 The Environment Agency is the leading public body protecting and improving the environment in England and Wales. It’s our job to make sure that air, land and water are looked after by everyone in today’s society, so that tomorrow’s generations inherit a cleaner, healthier world. Our work includes tackling flooding and pollution incidents, reducing industry’s impacts on the environment, cleaning up rivers, coastal waters and contaminated land, and improving wildlife habitats. This report is the result of research funded by NERC and supported by the Environment Agency’s Science Programme. Published by: Dissemination Status: Environment Agency, Rio House, Waterside Drive, Released to all regions Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4UD Publicly available Tel: 01454 624400 Fax: 01454 624409 www.environment-agency.gov.uk Keywords: hyporheic zone, groundwater-surface water ISBN: 978-1-84911-131-7 interactions © Environment Agency – October, 2009 Environment Agency’s Project Manager: Joanne Briddock, Yorkshire and North East Region All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Science Project Number: SC050070 The views and statements expressed in this report are those of the author alone. The views or statements Product Code: expressed in this publication do not necessarily SCHO1009BRDX-E-P represent the views of the Environment Agency and the Environment Agency cannot accept any responsibility for such views or statements. This report is printed on Cyclus Print, a 100% recycled stock, which is 100% post consumer waste and is totally chlorine free. -

Student Communes, Political Counterculture, and the Columbia University Protest of 1968

THE POLITICS OF SPACE: STUDENT COMMUNES, POLITICAL COUNTERCULTURE, AND THE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PROTEST OF 1968 Blake Slonecker A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Peter Filene Reader: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Reader: Jerma Jackson © 2006 Blake Slonecker ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT BLAKE SLONECKER: The Politics of Space: Student Communes, Political Counterculture, and the Columbia University Protest of 1968 (Under the direction of Peter Filene) This thesis examines the Columbia University protest of April 1968 through the lens of space. It concludes that the student communes established in occupied campus buildings were free spaces that facilitated the protestors’ reconciliation of political and social difference, and introduced Columbia students to the practical possibilities of democratic participation and student autonomy. This thesis begins by analyzing the roots of the disparate organizations and issues involved in the protest, including SDS, SAS, and the Columbia School of Architecture. Next it argues that the practice of participatory democracy and maintenance of student autonomy within the political counterculture of the communes awakened new political sensibilities among Columbia students. Finally, this thesis illustrates the simultaneous growth and factionalization of the protest community following the police raid on the communes and argues that these developments support the overall claim that the free space of the communes was of fundamental importance to the protest. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Peter Filene planted the seed of an idea that eventually turned into this thesis during the sort of meeting that has come to define his role as my advisor—I came to him with vast and vague ideas that he helped sharpen into a manageable project. -

The Personal Account of an American Revolutionary and Member Ofthe Weather Underground

The Personal Account of an American Revolutionary and Member ofthe Weather Underground Mattie Greenwood U.S. in the 20th Century World February, 10"'2006 Mr. Brandt OH GRE 2006 1^u St-Andrew's EPISCOPAL SCHOOL American Century Oral History Project Interviewee Release Form I, I-0\ V 3'CoVXJV 'C\V-\f^Vi\ {\ , hereby give and grant to St. Andrew's (inter\'iewee) Episcopal School the absolute and unqualified right to the use ofmy oral histoiy memoir conducted by VA'^^X'^ -Cx^^V^^ Aon 1/1 lOip . I understand that (student interviewer) (date) the purpose ofthis project is to collect audio- and video-taped oral histories of fust-hand memories ofa particular period or event in history as part ofa classroom project (The American Century Projeci), I understand that these interviews (tapes and transcripts) will be deposited in the Saint Andrew's Episcopal School library and archives for the use by future students, educators and researchers. Responsibility for the creation of derivative works will be at the discretion ofthe librarian, archivist and/or project coordinator. 1 also understand that the tapes and transcripts may be used in public presentations including, but not limited to, books, audio or video documentaries, slide-tape presentations, exhibits, articles, public performance, or presentation on the World Wide Web at the project's web site www.americancenturyproject.org or successor technologies. In making this contract I understand that J am sharing with St. Andrew's Episcopal School librai"y and archives all legal title and literar)' property rights which J have or may be deemed to have in my interview as well as my right, title and interest in any copyright related to this oral history interview which may be secured under the laws now or later in force and effect in the United Slates of America. -

Living with Karst Booklet and Poster

Publishing Partners AGI gratefully acknowledges the following organizations’ support for the Living with Karst booklet and poster. To order, contact AGI at www.agiweb.org or (703) 379-2480. National Speleological Society (with support from the National Speleological Foundation and the Richmond Area Speleological Society) American Cave Conservation Association (with support from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation and a Section 319(h) Nonpoint Source Grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Kentucky Division of Water) Illinois Basin Consortium (Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky State Geological Surveys) National Park Service U.S. Bureau of Land Management USDA Forest Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Geological Survey AGI Environmental Awareness Series, 4 A Fragile Foundation George Veni Harvey DuChene With a Foreword by Nicholas C. Crawford Philip E. LaMoreaux Christopher G. Groves George N. Huppert Ernst H. Kastning Rick Olson Betty J. Wheeler American Geological Institute in cooperation with National Speleological Society and American Cave Conservation Association, Illinois Basin Consortium National Park Service, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, USDA Forest Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey ABOUT THE AUTHORS George Veni is a hydrogeologist and the owner of George Veni and Associates in San Antonio, TX. He has studied karst internationally for 25 years, serves as an adjunct professor at The University of Ernst H. Kastning is a professor of geology at Texas and Western Kentucky University, and chairs Radford University in Radford, VA. As a hydrogeolo- the Texas Speleological Survey and the National gist and geomorphologist, he has been actively Speleological Society’s Section of Cave Geology studying karst processes and cavern development for and Geography over 30 years in geographically diverse settings with an emphasis on structural control of groundwater Harvey R. -

1961-1962. Bulletin and College Roster. Hope College

Hope College Digital Commons @ Hope College Hope College Catalogs Hope College Publications 1961 1961-1962. Bulletin and College Roster. Hope College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.hope.edu/catalogs Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Hope College, "1961-1962. Bulletin and College Roster." (1961). Hope College Catalogs. 130. http://digitalcommons.hope.edu/catalogs/130 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Hope College Publications at Digital Commons @ Hope College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hope College Catalogs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Hope College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOPE COLLEGE BULLETIN COLLEGE ROSTER TABLE OF CONTENTS C O L L E G E R O S T E R page The College Staff - Fall 1961 2 Administration 2 Faculty 4 The Student Body - Fall 1961 7 Seniors 7 Juniors 9 Sophomores 12 Freshmen 16 Special Students 19 Summer School Students - Fall 1961 21 Hope College Campus 21 Vienna Campus 23 COLLEGE DIRECTORY Fall 1961 (Home and college address and phone numbers) The College Staff 25 Students 29 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Library Information 58 Health Service 59 College Residences 60 College Telephones 61 NEW STAFF MEMBERS-SECOND SEMESTER Name Home Address College Address Phone Coates, Mary 110 E. 10th St. Durfee Hall EX 6-7822 Drew, Charles 50 E. Central Ave., Zeeland P R 2-2938 Fried, Paul 18 W. 12th St. Van Raalte 308 E X 6-5546 Loveless, Barbara 187 E. 35th St. E X 6-5448 Miller, James 1185 E. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS June 4, 1976 Mr

16728 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS June 4, 1976 Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Yes. speeded up the work of the Senate, and on Monday, and by early I mean as early Mr. ALLEN. The Senator spoke of pos I am glad the distinguished assistant ma as very shortly after 11 a.m., and that a sible quorum calls and votes on Monday. jority leader is now following that policy. long working day is in prospect for I would like to comment that I feel the [Laughter.] Monday. present system under which we seem to Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Well, my dis be operating, of having all quorum calls tinguished friend is overly charitable to RECESS TO MONDAY, JUNE 7, 1976, go live, has speeded up the work of the day in his compliments, but I had sought AT 11 A.M. Senate. There has only been one quorum earlier today to call off that quorum call call today put in by the distinguished as but the distinguished Senator from Ala Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, sistant majority leader, and I think the bama, noting that in his judgment I un if there be no further business to come Members of the Senate, realizing that doubtedly was seeking to call off the before the Senate, I move, in accordance a quorum call is going to go live, causes quorum call for a very worthy purpose, with the order previously entered, that them to come over to the Senate Cham went ahead to object to the calling off of the Senate stand in recess until the hour ber when a quorum call is called. -

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Individual and Organizational Donors

INDIVIDUAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL Illinois Tool Works Foundation Colliers International The Irving Harris Foundation Community Memorial Foundation DONORS J.R. Albert Foundation Crain's Chicago Business Jones Lang LaSalle Patrick and Anna M. Cudahy Fund $100,000 and above The Joyce Foundation Cushman & Wakefield of Illinois, Inc. Anonymous (8) Julie and Brian Simmons Foundation The Damico Family Foundation The Aidmatrix Foundation Knight Family Foundation Mr. Floyd E. Dillman and Dr. Amy Weiler Bank of America Russell and Josephine Kott DLA Piper LLP (US) Charter One Memorial Charitable Trust Eagle Seven, LLC The Chicago Community Trust Henrietta Lange Burk Fund The Earl and Brenda Shapiro Foundation Feeding America Levenfeld Pearlstein, LLC Eastdil Secured Daniel Haerther Living Trust Chicago and NW Mazda Dealers C. J. Eaton Hillshire Brands Foundation Mr. Clyde S. McGregor and Edelstein Foundation JPMorgan Chase Ms. LeAnn Pedersen Pope Eli and Dina Field Family Foundation Mr. Michael L. Keiser and Mrs. Rosalind Keiser Elizabeth Morse Genius Charitable Trust Mr. and Mrs. Eugene F. Fama Kraft Foods Foundation Mr. Saumya Nandi and Ms. Martha Delgado Mr. and Mrs. James Ferry, III Mr. Irving F. Lauf, Jr. Mr. and Mrs. David J. Neithercut Fortune Brands, Inc. Ann and Robert H. Lurie Foundation Dr. Tim D. Noel and Mrs. Joni L. Noel Franklin Philanthropic Foundation McDonald's Corporation Ms. Abby H. Ohl and Mr. Arthur H. Ellis Garvey's Office Products Polk Bros. Foundation The John C. & Carolyn Noonan GE Foundation J.B. and M.K. Pritzker Family Foundation Parmer Private Foundation General Iron Industries Charitable Foundation The Retirement Research Foundation Ms. Laura S. -

Bolivia Uprising, P.7 Weather Underground, P

HOME FRONT BUBBA MILITARY FAMILIES SPEAK OUT 3 FESSES UP 5 THE INDYPENDENT THE NEW YORK CITY INDEPENDENT MEDIA CENTER ISSUE #40 OCTOBER 25–NOVEMBER 11, 2003 WWW.NYC.INDYMEDIA.ORG THE TIPPING POINT ILLUSTRATION: MICHAEL ULRICH ILLUSTRATION: editorial It’s no exaggeration to say that the next 12 months may be one of the most important years ever in America’s history. The presidency of George W. Bush is unraveling, reveal- ing a morass of deceit, corruption and gangsterism. he war against Iraq has degenerated into a quagmire, Democrats both conspire to oust the government of Hugo more to the IMF than his own people. as more and more GIs and Iraqis are fed into the meat Chavez because he demands that the poor have a right to the Here at home, from the Battle of Seattle in December Tgrinder. It’s a combination of imperial religious cru- nation’s wealth. The Palestinians have been abandoned to 1999 to the millions in the streets last Feb. 15 opposing sade and gun-slinging treasure hunt, like the Spanish the regime of terror Israel inflicts upon them daily. In Asia, the war and the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride, we’ve Conquistadors wiping out the Aztecs and making off with a Bush is heaping weapons on autocratic regimes that desper- seen the greatest outpouring of dissent in a generation. mountain of gold. Raids and detention camps are higher pri- ately want to portray homegrown conflicts over poverty and Come next November, it's payback time. Bush’s poll orities than restoring water and electricity for Iraqi families. -

Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960S Through the 1980S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2014 Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960s through the 1980s Jeffrey A. Kroessler John Jay College of Criminal Justice How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/38 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960s through to the 1980s Jeffrey A. Kroessler John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York ew York is no stranger to explosives. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Black Hand, forerunners of the Mafia, planted bombs at stores and residences belonging to successful NItalians as a tactic in extortion schemes. To combat this evil, the New York Police Department (NYPD) founded the Italian Squad under Lieutenant Joseph Petrosino, who enthusiastically pursued those gangsters. Petrosino was assassinated in Palermo, Sicily, while investigating the criminal back- ground of mobsters active in New York. The Italian Squad was the gen- esis of today’s Bomb Squad. In the early decades of the twentieth century, anarchists and labor radicals planted bombs, the most devastating the 63 64 Criminal Justice and Law Enforcement noontime explosion on Wall Street in 1920. That crime was never solved.1 The city has also had its share of lunatics. -

The Judicial Antidote to Judge Julius Hoffman Challenging Claims of Unilateral Executive Authority

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 50 Issue 4 Summer 2019 Article 12 2019 Judge Damon Keith: The Judicial Antidote to Judge Julius Hoffman Challenging Claims of Unilateral Executive Authority Ellen Yaroshevsky Follow this and additional works at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ellen Yaroshevsky, Judge Damon Keith: The Judicial Antidote to Judge Julius Hoffman Challenging Claims of Unilateral Executive Authority, 50 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 989 (). Available at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol50/iss4/12 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized editor of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Judge Damon Keith: The Judicial Antidote to Judge Julius Hoffman Challenging Claims of Unilateral Executive Authority Ellen Yaroshefsky* From some of the highly-publicized trials of the 1960s—namely the trials of the Chicago Eight, Panther Twenty-One, and Weathermen—we can draw indispensable lessons about the role of the judges in upholding and promoting a fair justice system. The contrast to Judge Julius Hoffman’s notorious injudicious conduct in the Chicago Eight case is the courageous, thoughtful Judge Damon Keith, in the less publicized White Panther case in Detroit in the early 1970s. Judge Keith’s overriding sense of fairness exemplified the best of judicial independence in considering President Nixon’s claims of unilateral executive authority in United States v. Ayers and United States v. U.S. District Court. Judge Keith’s exemplary judicial conduct is an embrace of judicial independence that provides inspiration in current times.