Making a Space for Song

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

The Fingerprints of the “5” Royales Nearly 65 Years After Forming in Winston-Salem, the “5” Royales’ Impact on Popular Music Is Evident Today

The Fingerprints of the “5” Royales Nearly 65 years after forming in Winston-Salem, the “5” Royales’ impact on popular music is evident today. Start tracing the influences of some of today’s biggest acts, then trace the influence of those acts and, in many cases, the trail winds back to the “5” Royales. — Lisa O’Donnell CLARENCE PAUL SONGS VOCALS LOWMAN “PETE” PAULING An original member of the Royal Sons, the group that became the The Royales made a seamless transition from gospel to R&B, recording The Royales explored new terrain in the 1950s, merging the raw emotion of In the mid-1950s, Pauling took over the band’s guitar duties, adding a new, “5” Royales, Clarence Paul was the younger brother of Lowman Pauling. songs that included elements of doo-wop and pop. The band’s songs, gospel with the smooth R&B harmonies that were popular then. That new explosive dimension to the Royales’ sound. With his guitar slung down to He became an executive in the early days of Motown, serving as a mentor most of which were written by Lowman Pauling, have been recorded by a sound was embraced most prominently within the black community. Some his knees, Pauling electrified crowds with his showmanship and a crackling and friend to some of the top acts in music history. diverse array of artists. Here’s the path a few of their songs took: of those early listeners grew up to put their spin on the Royales’ sound. guitar style that hinted at the instrument’s role in the coming decades. -

Doo-Wop (That Thing)”

“Respect is just a minimum”: Self-empowerment in Lauryn Hill’s “Doo-Wop (That Thing)” Maisie Hulbert University of Cambridge 3,995 words Maisie Hulbert Self-empowerment in Lauryn Hill In his 2016 Man Booker Prize winning satirical novel The Sellout, Paul Beatty’s narrator states that “the black experience used to come with lots of bullshit, but at least there was some fucking privacy” (p. 230). The global hip-hop industry admittedly circulates images of blackness that were once silenced, but on the terms of an economically and socially dominant order. The resulting fascination with stereotypes of blackness, essentialised by those in positions of corporate power, means hip-hop becomes an increasingly complex identity- forming tool for young people worldwide. From a series of case studies exploring young black women’s relationship to hip-hop, Lauren Leigh Kelly argues that many “construct their identities in relation to media representations of blackness and femininity in hip-hop music and culture” (2015, p. 530). However, the stereotypical images of blackness which are encouraged ignore elements of choice, empowerment and re-contextualisation in hip-hop whilst meeting the widespread demand for imagery of a racial “Other”. The often negative associations with such images denies individuals the opportunity to identify their own relationship towards them, independent of media scrutiny and judgement. Lauryn Hill’s “Doo Wop (That Thing)” “sounds gender” (Bradley, 2015) through lyrics, flow, and multimedia, working to empower black femininities with self-respect. I argue that Hill’s track voices specifically black female concerns, prioritising notions of community central to black feminist thought (Collins, 2009). -

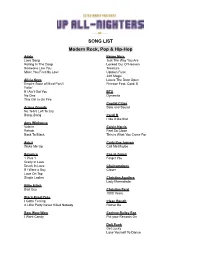

Band Song-List

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Thematic Lesson: Love Songs

THEMATIC LESSON: LOVE SONGS OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION Why is the Pop song such a common medium for expressing feelings about love, and how do individual songs relate to their historical moments? OVERVIEW The love song has been around for thousands of years and existed in virtually every culture: fragments of love songs and lyric poetry etched on papyrus and carved in stone survive from ancient Greece and Egypt. Medieval troubadours perfected the art of writing and singing about idealized love. Opera composers dramatized romance in music. Amorous parlor songs played a role in courtships. And of course, love songs are a fixture in contemporary musical culture. By most estimates, they have made up the majority of songs on the popularity charts throughout the 20th century and into the 21st. Musicians working in every major genre of American popular music—including Folk, Jazz, Pop, Country, Rhythm and Blues, and Rock and Roll — have produced songs about love. The variety of themes is similarly broad, encompassing many different aspects of and perspectives on relationships, from loss and longing to hope and dreaming. Rock and Roll love songs inherit much from their historical predecessors, but they also demonstrate how cultural ideas about love, sex, and relationships change over time. New musical styles present opportunities to approach an old subject in new ways, and the sometimes raucous sounds of Rock and Roll made entirely new types of songs about love possible. In this lesson, students will listen to examples of love songs from several musical styles and historical moments. The activities are designed to explore how music and lyrics work together to express different sentiments toward love and relationships. -

Postmodern Jukebox and Straight No Chaser Announce 25-City Summer Us Tour Launching July 13 in Chicago

POSTMODERN JUKEBOX AND STRAIGHT NO CHASER ANNOUNCE 25-CITY SUMMER US TOUR LAUNCHING JULY 13 IN CHICAGO First Co-Headlining Tour Brings Together Vintage Pop Sensation PMJ’s Full-Band Extravaganza And A Cappella Superstars SNC’s Jaw-Dropping Vocal Artistry LOS ANGELES (Feb. 14, 2017) – Fans of retro pop sounds with a cheeky modern twist are in for the experience of a lifetime this summer as Postmodern Jukebox and Straight No Chaser join forces for a co-headlining tour of the United States. Produced exclusively by Live Nation, the 25-city jaunt kicks off in Chicago on July 13 and will include stops in Cleveland, Boston, Nashville and Los Angeles for the two classic-meets-contemporary sensations, both of whom mash up classic pop stylings and modern pop hits in their own unique fashions. Complete itinerary below. Presale for both fan clubs begin on Wednesday, February 15th at 10am local time through 10pm. More information including VIP Packages can be found at http://www.sncmusic.com/ and http://postmodernjukebox.com/. As the official credit card for the tour, Citi® / AAdvantage® cardmembers will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning Thursday, February 16th at 10am local time through Friday, February 17th at 10pm local time. For complete details, please visit citiprivatepass.com. General on sale begins February 18 at 10am local time at livenation.com. Both bands deliver contemporary pop songs with timeless flair - the stylistic diversity, real musical and vocal skill, and dedication to craft of a bygone era. Straight No Chaser shirk the blazers and khakis of campus a cappella groups for something far less strait-laced (or straight-faced), training their jaw-dropping vocal prowess and soulful harmonies on past and current hits. -

Sweet Adelines International Arranged Music List

Sweet Adelines International Arranged Music List ID# Song Title Arranger I03803 'TIL I HEAR YOU SING (From LOVE NEVER DIES) June Berg I04656 (YOUR LOVE HAS LIFTED ME) HIGHER AND HIGHER Becky Wilkins and Suzanne Wittebort I00008 004 MEDLEY - HOW COULD YOU BELIEVE ME Sylvia Alsbury I00011 005 MEDLEY - LOOK FOR THE SILVER LINING Mary Ann Wydra I00020 011 MEDLEY - SISTERS Dede Nibler I00024 013 MEDLEY - BABY WON'T YOU PLEASE COME HOME* Charlotte Pernert I00027 014 MEDLEY - CANADIAN MEDLEY/CANADA, MY HOME* Joey Minshall I00038 017 MEDLEY - BABY FACE Barbara Bianchi I00045 019 MEDLEY - DIAMONDS - CONTEST VERSION Carolyn Schmidt I00046 019 MEDLEY - DIAMONDS - SHOW VERSION Carolyn Schmidt I02517 028 MEDLEY - I WANT A GIRL Barbara Bianchi I02521 031 MEDLEY - LOW DOWN RYTHYM Barbara NcNeill I00079 037 MEDLEY - PIGALLE Carolyn Schmidt I00083 038 MEDLEY - GOD BLESS THE U.S.A. Mary K. Coffman I00139 064 CHANGES MEDLEY - AFTER YOU'VE GONE* Bev Sellers I00149 068 BABY MEDLEY - BYE BYE BABY Carolyn Schmidt I00151 070 DR. JAZZ/JAZZ HOLIDAY MEDLEY - JAZZ HOLIDAY, Bev Sellers I00156 072 GOODBYE MEDLEY - LIES Jean Shook I00161 074 MEDLEY - MY BOYFRIEND'S BACK/MY GUY Becky Wilkins I00198 086 MEDLEY - BABY LOVE David Wright I00205 089 MEDLEY - LET YOURSELF GO David Briner I00213 098 MEDLEY - YES SIR, THAT'S MY BABY Bev Sellers I00219 101 MEDLEY - SOMEBODY ELSE IS TAKING MY PLACE Dave Briner I00220 102 MEDLEY - TAKE ANOTHER GUESS David Briner I02526 107 MEDLEY - I LOVE A PIANO* Marge Bailey I00228 108 MEDLEY - ANGRY Marge Bailey I00244 112 MEDLEY - IT MIGHT -

A Concept Album

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Honors Program Contracts Honors Program Spring 2020 The Power of Protest Music: A Concept Album Matthew Patterson Merrimack College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_component Part of the Music Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Patterson, Matthew, "The Power of Protest Music: A Concept Album" (2020). Honors Program Contracts. 20. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_component/20 This Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Program Contracts by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Matthew Patterson Dr. Anne Flaherty and Dr. Laura Pruett Music and Politics FAA/POL3171 6 May 2020 The Power of Protest Music: A Concept Album Introduction: This semester, I decided to create an honors contract for one of my favorite classes offered at Merrimack, Music and Politics. Both music and politics are two of my biggest interests, so I felt that this class would allow me to create a very unique final project. For my project, I decided to create my own political concept album that would analyze the role of music in certain social and political movements. Inspired by old vinyl records, this curation will contain 12 songs that are divided evenly on each side of the record. Side A will contain six songs that are considered anthems of the Civil Rights Movement, while Side B will contain six songs that are considered anthems for the Black Lives Matter Movement. -

Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Aint Too Proud To

Ain't Nothing Like The Real Thing -Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Aint Too Proud To Beg -The Temptations All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor At Last - Etta James Bang Bang – Nicki Minaj Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Blame It On The Alcohol – Jamie Foxx Blank Space – Taylor Swift Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke Boo'd Up - Ella Mai Boogie Man- KC & The Sunshine Band Boogie Oogie Oogie - Taste Of Honey Boom Shake The Room – DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince Brick House -The Commodores Bust A Move – Young MC Can’t Feel My face – The Weekend Can't Get Next To You -The Temptations Can't Help Falling In Love - UB40 Can’t Keep My Hands To Myself – Selena Gomez Can’t Stop The Feelin – Justin Timberlake Can't Take My Eyes Off Of You -Frankie Valley & 4 Seasons Chain Of Fools -Aretha Franklin Chandelier – Sia Closer - Chainsmokers Come Away with me - Norah Jones Confident – Demi Lovato Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Crazy In Love – Beyonce Da Butt – E.W. Dance To The Music -Sly & The Family Stone Dancing In The Street -Martha Reeves & The Vandellas Dangerously In Love – Beyonce Déjà vu – Beyonce DJ Got Us Fallin In Love – Usher Doo Wop – Lauryn Hill Don’t Stop ‘Till You Get Enough – Michael Jackson Don’t Stop Believin’ -- Journey Don't Know Why - Norah Jones Drunk In Love - Beyonc ft Jay Z Dynomite – Taio Cruz Everybody Dance Now – C&C And Music Factory Everybody Dance Now C & C -Dance Factory Everyday People -Sly & The Family Stone Feel Like A Woman – Shania Twain Finesse – Bruno Mars Firework – Katy Perry Fancy – Iggy Azalea Forget You – Cee Lo Green Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air – Will Smith Funky Broadway -Wilson Picket Get Down Tonight -K.C. -

Lista De Músicas

VIDEOKÊ Pacote INT09 A GUARULHOS 40 americanas 11-2440-3717 LISTA DE MÚSICAS CANTOR CÓD TÍTULO ÍNICIO DA LETRA 40 nacionais Adele 19678 WATER UNDER THE BRIDGE If you're not the one for me Aerosmith 19658 JADED Hey j-j-jaded you got your mama's style Ashley Tisdale 19643 BE GOOD TO ME Everyday is getting worse Avril Lavigne 19654 HE WASN'T There's not much going on today Backstreet Boys 19673 THE ONE I'll be the one Beach Boys (The) 19670 SURFIN' USA If everybody had an ocean Bee Gees 19674 TRAGEDY Here I lie In a lost and lonely part of town Black Eyed Peas 19680 WHERE IS THE LOVE? What's wrong with the world mama Bon Jovi 19671 THANK YOU FOR LOVING ME It's hard for me to say the things Britney Spears 19669 STRONGER Uh hey yeah hush just stop there's nothing Bruno Mars 19675 TREASURE Give me your give me your Carpenters 19668 SING Sing sing a song Celine Dion 19657 IT'S ALL COMING BACK TO ME NOW There were nights when the wind was so Christina Aguilera - Lil' Kim - Maya - Pink 19659 LADY MARMALADE Where'scold all may soul sisters Chumbawamba 19676 TUBTHUMPING We'll be singing when we're winning Coolio - L.V. 19653 GANGSTA'S PARADISE As I walk through the valley of the shadow Culture Club 19660 LOVE IS LOVE You don't have to touch it to know Damien Rice 19672 THE BLOWER'S DAUGHTER And so it is Destiny's Child 19667 SAY MY NAME Say my name say my name Foreigner 19677 WAITING FOR A GIRL LIKE YOU So long I've been looking too hard Frank Sinatra 19646 CHEEK TO CHEEK Heaven I'm in heaven Jason Mraz 19662 LOVE SOMEONE Love is a funny thing Lauryn -

![3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1496/3-smack-that-eminem-feat-eminem-akon-shady-convict-2571496.webp)

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM thing on Get a little drink on (feat. Eminem) They gonna flip for this Akon shit You can bank on it! [Akon:] Pedicure, manicure kitty-cat claws Shady The way she climbs up and down them poles Convict Looking like one of them putty-cat dolls Upfront Trying to hold my woodie back through my Akon draws Slim Shady Steps upstage didn't think I saw Creeps up behind me and she's like "You're!" I see the one, because she be that lady! Hey! I'm like ya I know lets cut to the chase I feel you creeping, I can see it from my No time to waste back to my place shadow Plus from the club to the crib it's like a mile Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini away Gallardo Or more like a palace, shall I say Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Plus I got pal if your gal is game TaeBo In fact he's the one singing the song that's And possibly bend you over look back and playing watch me "Akon!" [Chorus (2X):] [Akon:] Smack that all on the floor I feel you creeping, I can see it from my Smack that give me some more shadow Smack that 'till you get sore Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini Smack that oh-oh! Gallardo Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Upfront style ready to attack now TaeBo Pull in the parking lot slow with the lac down And possibly bend you over look back and Convicts got the whole thing packed now watch me Step in the club now and wardrobe intact now! I feel it down and cracked now (ooh) [Chorus] I see it dull and backed now I'm gonna call her, than I pull the mack down Eminem is rollin', d and em rollin' bo Money -

How They Got Over: a Brief Overview of Black Gospel Quartet Music

How They Got Over: A Brief Overview of Black Gospel Quartet Music Jerry Zolten October 29, 2015 Jerry Zolten is Associate Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences, American Studies, and Integrative Arts at the Penn State-Altoona. his piece takes you on a tour through black gospel music history — especially the gospel quartets T — and along the way I’ll point you to some of the most amazing performances in African American religious music ever captured on film. To quote the late James Hill, my friend and longtime member of the Fairfield Four gospel quartet, “I don't want to make you feel glad twice—glad to see me come and glad to see me go.” With that in mind I’m going to get right down to the evolution from the spirituals of slavery days to the mid-twentieth century “golden age” of gospel. Along the way, we’ll learn about the a cappella vocal tradition that groups such as the Fairfield Four so brilliantly represent today. The black gospel tradition is seeded in a century and a half of slavery and that is the time to begin: when the spirituals came into being. The spirituals evolved out of an oral tradition, sung solo or in groups and improvised. Sometimes the music is staid, sometimes histrionic. Folklorist Zora Neale Hurston famously described how spirituals were never sung the same way twice, “their truth dying under training like flowers under hot water.”1 We don’t know the names of the people who wrote these songs. They were not written down at the time.