Notes and Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Napoleon, Talleyrand, and the Future of France

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2017 Visionaries in opposition: Napoleon, Talleyrand, and the future of France Seth J. Browner Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Browner, Seth J., "Visionaries in opposition: Napoleon, Talleyrand, and the future of France". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2017. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/621 Visionaries in opposition: Napoleon, Talleyrand, and the Future of France Seth Browner History Senior Thesis Professor Kathleen Kete Spring, 2017 2 Introduction: Two men and France in the balance It was January 28, 1809. Napoleon Bonaparte, crowned Emperor of the French in 1804, returned to Paris. Napoleon spent most of his time as emperor away, fighting various wars. But, frightful words had reached his ears that impelled him to return to France. He was told that Joseph Fouché, the Minister of Police, and Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs, had held a meeting behind his back. The fact alone that Fouché and Talleyrand were meeting was curious. They loathed each other. Fouché and Talleyrand had launched public attacks against each other for years. When Napoleon heard these two were trying to reach a reconciliation, he greeted it with suspicion immediately. He called Fouché and Talleyrand to his office along with three other high-ranking members of the government. Napoleon reminded Fouché and Talleyrand that they swore an oath of allegiance when the coup of 18 Brumaire was staged in 1799. -

Catriona Helen Miller

Vlood Spirits A cjungian Approach to the Vampire JKyth Catriona Helen Miller Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Stirling Stirling Scotland December 1998 r., 4. , Dedication To my parents, Irene and Jack Miller, without whom.... For all the support, guidance and encouragement above and beyond the call of parental duty. Your many favours can never be repaid. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. John Izod for the skillful and unfailingly tactful supervision of this thesis, and for the companionshipon the j ourney. To Lari, for the chair; the commas and comments;the perpetual phone calls; and for going to Santa Cruz with me all those years ago. To everybody in the Late Late Service for sustenanceof various kinds. And everyone else who asked about my thesis and then listened to the answer without flinching. I also acknowledge the kind financial support of the Glasgow Society for Sons and Daughters of Ministers of the Church of Scotland, and, of course, my parents. Contents Page Acknowlegements i Abstract .v INTRODUCTION PART ONE APPROACH & CONTEXT 10 " The Study of Myth & the Cartesian/Newtonian Framework 11 " The Advent of Psychology 13 " Freud & the Vampire Myth 17 " Beyond Descartes & Newton: the New Paradigm 21 " Jung & the New Model 24 " Archetypes & the Collective Unconscious 31 " The Study of Myth After Freud & Jung 35 The Vampire Myth 40 " I " Jung & the Vampire Myth 41 " Symbols: A Jungian Definition 44 PART TWO ENCOUNTERS WITH SHADOW VAMPIRES 49 " Folklore & Fiction 49 " The Vampire in Folklore 51 " Vampirý Epidemics? 54 " The Shadow Archetype 57 " The Dead 58 " The Living Dead 61 " The Shadow Vampire in the Twentieth Century 65 " Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (Dir: F. -

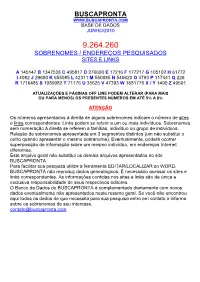

Buscapronta Base De Dados Junho/2010

BUSCAPRONTA WWW.BUSCAPRONTA.COM BASE DE DADOS JUNHO/2010 9.264.260 SOBRENOMES / ENDEREÇOS PESQUISADOS SITES E LINKS A 145147 B 1347538 C 495817 D 276690 E 17216 F 177217 G 105102 H 61772 I 4082 J 29600 K 655085 L 42311 M 550085 N 540620 O 4793 P 117441 Q 226 R 1716485 S 1089982 T 71176 U 35625 V 47393 W 1681776 X / Y 1490 Z 49591 ATUALIZAÇÕES E PÁGINAS OFF LINE PODEM ALTERAR (PARA MAIS OU PARA MENOS) OS PRESENTES NÚMEROS EM ATÉ 5% A 8% ATENÇÃO Os números apresentados à direita de alguns sobrenomes indicam o número de sites e links correspondentes. Links podem se referir a um ou mais indivíduos. Sobrenomes sem numeração à direita se referem a famílias, indivíduo ou grupo de indivíduos. Relação de sobrenomes apresentada em 3 segmentos distintos (um não substitui o outro quando apresentar o mesmo sobrenome). Eventualmente, poderá ocorrer superposição de informação sobre um mesmo indivíduo, em endereços Internet diferentes. Este arquivo geral não substitui os demais arquivos apresentados no site BUSCAPRONTA. Para facilitar sua pesquisa utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR so WORD. BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos. È necessário acessar os sites e links correspondentes. As informações contidas nos sites e links são de única e exclusiva responsabilidade de seus respectivos editores. O Banco de Dados do BUSCAPRONTA é complementado diariamente com novos dados eventualmente não apresentados neste resumo geral. Se você não encontrou aqui todos os dados de que necessita para sua pesquisa entre em contato e informe sobre os sobrenomes -

The Proto-Filmic Monstrosity of Late Victorian Literary Figures

Bamberger Studien zu Literatur, 14 Kultur und Medien “Like some damned Juggernaut” The proto-filmic monstrosity of late Victorian literary figures Johannes Weber 14 Bamberger Studien zu Literatur, Kultur und Medien Bamberger Studien zu Literatur, Kultur und Medien hg. von Andrea Bartl, Hans-Peter Ecker, Jörn Glasenapp, Iris Hermann, Christoph Houswitschka, Friedhelm Marx Band 14 2015 “Like some damned Juggernaut” The proto-filmic monstrosity of late Victorian literary figures Johannes Weber 2015 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de/ abrufbar. Diese Arbeit hat der Fakultät Geistes- und Kulturwissenschaften der Otto-Friedrich- Universität Bamberg als Dissertation vorgelegen. 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Christoph Houswitschka 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jörn Glasenapp Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 28. Januar 2015 Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über den Hochschulschriften-Server (OPUS; http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-bamberg/) der Universitätsbibliothek Bamberg erreichbar. Kopien und Ausdrucke dürfen nur zum privaten und sons- tigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden. Herstellung und Druck: Docupoint, Magdeburg Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press, Anna Hitthaler Umschlagbild: Screenshot aus Vampyr (1932) © University of Bamberg Press Bamberg 2015 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp/ ISSN: 2192-7901 ISBN: 978-3-86309-348-8 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-349-5 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-267683 Danksagung Mein besonderer Dank gilt meinem Bruder Christian für seinen fachkundigen Rat und die tatkräftige Unterstützung in allen Phasen dieser Arbeit. Ich danke meinem Doktorvater Prof. Dr. Christoph Houswitschka für viele wichtige Denkanstöße und Freiräume. -

The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. Vol. III

The Life Of Napoleon Bonaparte. Vol. III. By William Milligan Sloane LIFE OF NAPOLEON BONAPARTE CHAPTER I. WAR WITH RUSSIA: PULTUSK. Poland and the Poles — The Seat of War — Change in the Character of Napoleon's Army — The Battle of Pultusk — Discontent in the Grand Army — Homesickness of the French — Napoleon's Generals — His Measures of Reorganization — Weakness of the Russians — The Ability of Bennigsen — Failure of the Russian Manœuvers — Napoleon in Warsaw. 1806-07. The key to Napoleon's dealings with Poland is to be found in his strategy; his political policy never passed beyond the first tentative stages, for he never conquered either Russia or Poland. The struggle upon which he was next to enter was a contest, not for Russian abasement but for Russian friendship in the interest of his far-reaching continental system. Poland was simply one of his weapons against the Czar. Austria was steadily arming; Francis received the quieting assurance that his share in the partition was to be undisturbed. In the general and proper sorrow which has been felt for the extinction of Polish nationality by three vulture neighbors, the terrible indictment of general worthlessness which was justly brought against her organization and administration is at most times and by most people utterly forgotten. A people has exactly the nationality, government, and administration which expresses its quality and secures its deserts. The Poles were either dull and sluggish boors or haughty and elegant, pleasure- loving nobles. Napoleon and his officers delighted in the life of Warsaw, but he never appears to have respected the Poles either as a whole or in their wrangling cliques; no doubt he occasionally faced the possibility of a redeemed Poland, but in general the suggestion of such a consummation served his purpose and he went no further. -

Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte — Volume 15

Memoirs Of Napoleon Bonaparte — Volume 15 By Louis Antoine Fauvelet De Bourrienne Memoirs Of Napoleon Bonaparte CHAPTER XI. 1815. My departure from Hamburg-The King at St. Denis—Fouche appointed Minister of the Police—Delay of the King's entrance into Paris— Effect of that delay—Fouche's nomination due to the Duke of Wellington— Impossibility of resuming my post—Fouche's language with respect to the Bourbons—His famous postscript—Character of Fouche—Discussion respecting the two cockades—Manifestations of public joy repressed by Fouche—Composition of the new Ministry— Kind attention of Blucher— The English at St. Cloud—Blucher in Napoleon's cabinet—My prisoner become my protector—Blucher and the innkeeper's dog—My daughter's marriage contract—Rigid etiquette— My appointment to the Presidentship of the Electoral College of the Yonne—My interview with Fouche—My audience of the King—His Majesty made acquainted with my conversation with Fouche—The Duke of Otranto's disgrace—Carnot deceived by Bonaparte—My election as deputy—My colleague, M. Raudot—My return to Paris—Regret caused by the sacrifice of Ney—Noble conduct of Macdonald—A drive with Rapp in the Bois de Boulogne—Rapp's interview with Bonaparte in 1815—The Due de Berri and Rapp—My nomination to the office of Minister of State—My name inscribed by the hand of Louis XVIII.— Conclusion. The fulfilment of my prediction was now at hand, for the result of the Battle of Waterloo enabled Louis XVIII. to return to his dominions. As soon as I heard of the King's departure from Ghent I quitted Hamburg, and travelled with all possible haste in the hope of reaching Paris in time to witness his Majesty's entrance. -

Hobhouse and the Hundred Days

116 The Hundred Days, March 11th-July 24th 1815 The Hundred Days March 11th-July 24th 1815 Edited from B.L.Add.Mss. 47232, and Berg Collection Volumes 2, 3 and 4: Broughton Holograph Diaries, Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Saturday March 11th 1815: Received this morning from my father the following letter: Lord Cochrane has escaped from prison1 – Bounaparte has escaped from Elba2 – I write this from the House of Commons and the intelligence in both cases seems to rest on good authority and is believed. Benjamin Hobhouse Both are certainly true. Cullen3 came down today and confirmed the whole of both. From the first I feel sure of Napoleon’s success. I received a letter [from] Lord John Townshend4 apologising for his rudeness, but annexing such comments as require a hint from me at the close of the controversy. Sunday March 12th 1815: Finish reading the Αυτοχεδιοι Ετοχασµοι of Coray.5 1: Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald (1775-1860) admiral. Implicated unfairly in a financial scandal, he had been imprisoned by the establishment enemies he had made in his exposure of Admiralty corruption. He was recaptured (see below, 21 Mar 1815). He later became famous as the friend and naval assistant of Simon Bolivar. 2: Napoleon left Elba on March 26th. 3: Cullen was a lawyer friend of H., at Lincoln’s Inn. 4: Lord John Townshend. (1757-1833); H. has been planning to compete against his son as M.P. for Cambridge University, which has made discord for which Townshend has apologised. -

Appendix 1: Dynasty, Nobility and Notables of the Napoleonic Empire

Appendix 1: Dynasty, Nobility and Notables of the Napoleonic Empire A Napoleon Emperor of the French, Jg o~taly, Mediator of the Swiss Confederation, Protector of the Confederation of the Rhine, etc. Princes of the first order: memtrs of or\ose related by marriage to the Imperial family who became satellite kings: Joseph, king of Naples (March 1806) and then of Spain (June 1808); Louis, king of Holland (June 1806-July 1810); Ur6me, king of Westphalia (July 1807); Joachim Murat (m. Caroline Bonaparte), grand duke of Berg (March 1806) and king of Naples (July 1808) Princes(ses) of the selnd order: Elisa Bo~e (m. F6lix Bacciochi), princess of Piombino (1805) and of Lucca (1806), grand duchess of Tuscany (1809); Eug~ne de Beauharnais, viceroy ofltaly (June 1805); Berthier, prince ofNeuchitel (March 1806) and of Wagram (December 1809) Princes of the J order: Talleyrand, prince of Bene\ento (June 1806); Bernadotte, prince of Ponte Corvo (June 1806) [crown prince of Sweden, October 1810] The 22 recipien! of the 'ducal grand-fiefs of the Empire'\.eated in March 1806 from conquered lands around Venice, in the kingdom of Naples, in Massa-Carrara, Parma and Piacenza. Similar endowments were later made from the conquered lands which formed the duchy of Warsaw (July 1807) These weret.anted to Napoleon's top military commanders, in\uding most of the marshals, or to members of his family, and were convertible into hereditary estates (majorats) The duk!s, counts, barons and chevaliers of the Empire created after le March decrees of 1808, and who together -

An Honor Roll Containing a Pictorial Record of the Gallant And

wmM, f J ,' Jl I f \ / ! ,7 .^ 1 ( l&^fiiBAiaB^v y/zp/zSorvoc/ fo AoGp t/ie/paf/on 9/„.'-%„or9?o/? s\ 1917'" 1918- 1919 [o '^CxCC ))ooo o PUBLISHED BY The Leader Publishing Company Pipestone, Minni^sota 1^ ^ HAY J* I9M ^ 1 A =_>< .25 Pipestone County^s Honored Dead PDiss ! CARI^ETON ASHTON — Pipe- m stone, Minn. Private, ist Co., ml Coast Defense Artillery. Entered service dis- I SSI November 30, 1914; cliarg^ed 191 7 because of physical disability. Died March 7, 1919. im\ PETER BARKER — Holland, Minn. Private, Infantry. En- tered service Oct. 23, 191 8; train- ed at Camp Cody, N. M. Died November 3, 1918, at Camp Cody, N. M., of influenza. I I! I li WALTER EDWARD BREI- IIOLZ—Holland, Minn. Pri- vate, Co. M, 53rd Inf. Entered service May i, 1918; trained at Camp W'adsworth, S. C. ; depart- ed overseas July, 1918; battles, Meuse and Argonne. Died De- cember 18, 1918, at Recy-Sur- Oise, France, peritonitis. '"^-"':g^MlMMlii^ili1 ; aummmiii fail Pipestone County's Honored Dead Hill IRVING BENJAMIN ENGEL- BART—Pipestone, Minn. Cor- poral, Co. B, 119th Inf. Entered service Feb. 28, 1918; trained at Camp Dodge ; departed overseas May 15, 1918. Killed in action September 29, 191 8. .:;ii VICTOR ELMER IIURD—Re- gina, Canada. Private, Infantrj'. Entered service Jnly, 1918; train- ed at Cam]:) Wadsvvorth, S. C. departed overseas Sept., 1918. Died October 10, 1918. in France, of pnenmonia. OLIVER SMITH HUVCK—Jas- per, Minn. Seaman, second class, U. S. S. Transport Bridgeport. Entered service Ma\', 1917; train- ed at Great Lakes Naval Train- ing Station. -

A Short History of the Great War - Title Page

A.F. Pollard - A Short History Of The Great War - Title Page A SHORT HISTORY OF THE GREAT WAR BY A. F. POLLARD M.A., Litt.D. FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE, OXFORD PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON WITH NINETEEN MAPS METHUEN & CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.C. LONDON file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Owner/My%20Documents/My%20eBooks/pollard/shogw10h/title.html12/03/2006 6:37:33 PM A.F. Pollard - A Short History Of The Great War - Note NOTE The manuscript of this book, except the last chapter, was finished on 21 May 1919, and the revision of the last chapter was completed in October. It may be some relief to a public, distracted by the apologetic deluge which has followed on the peace, to find how little the broad and familiar outlines of the war have thereby been affected. A. F. P. file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Owner/My%20Documents/My%20eBooks/pollard/shogw10h/note.html12/03/2006 6:37:33 PM A.F. Pollard - A Short History Of The Great War - Contents Page CONTENTS CHAP. I. THE BREACH OF THE PEACE II. THE GERMAN INVASION III. RUSSIA MOVES IV. THE WAR ON AND BEYOND THE SEAS V. ESTABLISHING THE WESTERN FRONT VI. THE FIRST WINTER OF THE WAR VII. THE FAILURE OF THE ALLIED OFFENSIVE VIII. THE DEFEAT OF RUSSIA IX. THE CLIMAX OF GERMAN SUCCESS X. THE SECOND WINTER OF THE WAR XI. THE SECOND GERMAN OFFENSIVE IN THE WEST XII. THE ALLIED COUNTER-OFFENSIVE XIII. THE BALKANS AND POLITICAL REACTIONS XIV. -

(1846–1920). Russian Jeweller, of French Descent. He Achieved Fame

Fabricius ab Aquapendente, Hieronymus (Geronimo Fabrizi) (1533–1619). Italian physician, born at Aquapendente, near Orvieto. He studied medicine under *Fallopio at Padua and succeeded F him as professor of surgery and anatomy 1562– 1613. He became actively involved in building Fabergé, Peter Carl (1846–1920). Russian jeweller, the university’s magnificent anatomical theatre, of French descent. He achieved fame by the ingenuity which is preserved today. He acquired fame as a and extravagance of the jewelled objects (especially practising physician and surgeon, and made extensive Easter eggs) he devised for the Russian nobility and contributions to many fields of physiology and the tsar in an age of ostentatious extravagance which medicine, through his energetic skills in dissection ended on the outbreak of World War I. He died in and experimentation. He wrote works on surgery, Switzerland. discussing treatments for different sorts of wounds, and a major series of embryological studies, illustrated Fabius, Laurent (1946– ). French socialist politician. by detailed engravings. His work on the formation of He was Deputy 1978–81, 1986– , Minister for the foetus was especially important for its discussion Industry and Research 1983–84, Premier of France of the provisions made by nature for the necessities 1984–86, Minister of Economics 2000–02 and of the foetus during its intra-uterine life. The medical Foreign Minister 2012–16, and President of the theory he offered to explain the development of eggs Constitutional Council 2016– . and foetuses, however, was in the tradition of *Galen. Fabricius is best remembered for his detailed studies Fabius Maximus Verrocosus Cunctator, Quintus of the valves of the veins. -

The Congress of Vienna

fast of Greenwich THE CONGRESS OF VIENNA A study tn Allied XJmty' 1812-1S22 HAROLD NICOLSON ‘Nothing appears of shape to utdicatc That cognisance has marshalled things tetrene, Or will (such IS my thinking) in my span Rather they show that, like a knitter droused Whose fingers play in skilled unmindfiilness. The Will has woven with an absent heed ’ Since life first was, and ever will so weave Thomas Hardy, The Dynastj ‘Historic sense forbids us to )udge results by motive, or real consequences by the ideals and intentions of the actor who produced them ’ Viscount Morley LONDON CONSTABLE & CO LTD The quotahon from Thomas Hardy on the title-page IS made with the kind permission ofMessts Macmillan <dy Co Ltd THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO ANTHONY EDEN CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY NOTE ------ xi I THE RETREAT FROM MOSCOW (OCTOBER 18-DECEMBER 18,1812)- ------- r II ‘the REVIVAL OF PRUSSIA’ (1812-1813) - - - 15 III THE INTERVENTION OF AUSTRIA (JUNE 1-AUGUST 12, 1813) -------- 30 IV THE FRANKFURT PROPOSALS (noVEMBER-DECEMBER 18:3) 46 V THE ADVENT OF CASTLEREAGH (jANUARY-MARCH 1814) - - - 63 VI THE FIRST PEACE OF PARIS (mAY 30, 1814) - - 82 VII LONDON INTERLUDE (jUNE 1814) - - - - lOI VIII THE CONGRESS ASSEMBLES (SEPTEMBER 1814) - - I18 IX THE PROBLEM OF PROCEDURE (OCTOBER 1814) - 1 34 X THE APPROACH TO THE POLISH PROBLEM (OCTOBER 1814) 148 XI THE POLISH NEGOTIATIONS (SEPTEMBER 1814-FEB- RUARY 1815)- - - - - - - 164 -^II. THE ITALIAN AND GERMAN SETTLEMENTS (fEBRUARY- MARCH 1815)- - - - - - -182 -XIII GENERAL QUESTIONS (fEBRUARY-MARCH 1815) - - 201 • XIV THE