Contraception Donald E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contraception Pearls for Practice

Contraception Pearls for Practice Academic Detailing Service Planning committee Content Experts Clinical reviewer Gillian Graves MD FRCS(C), Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University Drug evaluation pharmacist Pam McLean-Veysey BScPharm, Drug Evaluation Unit, Nova Scotia Health Family Physician Advisory Panel Bernie Buffett MD, Neils Harbour, Nova Scotia Ken Cameron BSc MD CCFP, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Norah Mogan MD CCFP, Liverpool, Nova Scotia Dalhousie CPD Bronwen Jones MD CCFP – Family Physician, Director Evidence-based Programs in CPD, Associate Professor, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University Michael Allen MD MSc – Family Physician, Professor, Post-retirement Appointment, Consultant Michael Fleming MD CCFP FCFP – Family Physician, Director Family Physician Programs in CPD Academic Detailers Isobel Fleming BScPharm ACPR, Director of Academic Detailing Service Lillian Berry BScPharm Julia Green-Clements BScPharm Kelley LeBlanc BScPharm Gabrielle Richard-McGibney BScPharm, BCPS, PharmD Cathy Ross RN BScNursing Thanks to Katie McLean, Librarian Educator, NSHA Central Zone for her help with literature searching. Cover artwork generated with Tagxedo.com Disclosure statements The Academic Detailing Service is operated by Dalhousie Continuing Professional Development, Faculty of Medicine and funded by the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness. Dalhousie University Office of Continuing Professional Development has full control over content. Dr Bronwen Jones receives funding for her Academic Detailing work from the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness. Dr Michael Allen has received funding from the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness for research projects and to develop CME programs. Dr Gillian Graves has received funding for presentations from Actavis (Fibristal®) and is on the board of AbbVie (for Lupron®). -

Copper Intrauterine Device (IUD)

Copper Intrauterine Device (IUD) What is it? An IUD is a small, flexible device which is inserted into the uterus by a health professional to prevent pregnancy. The copper IUD is a plastic frame with copper bands and/or wire. It has fine threads which extend through the cervix into the vagina. Once inserted, IUDs are not usually noticeable to you or your partner/s. How does it work? The copper IUD prevents pregnancy by: Quick Facts • affecting sperm movement so they cannot move through the uterus • affecting egg movement, and in the rare instance of an egg being A long-acting reversible fertilised, preventing the egg from attaching to the lining of the uterus. contraception (LARC). One of the most effective How effective is it? methods of contraception The copper IUD is more than 99% effective at preventing pregnancy and can last for 5-10 years (depending on the type). Copper IUDs inserted in available in Australia. people over 40 can be left until after menopause. Method Copper IUDs can also be used as a very effective form of emergency Non hormonal contraception, up to five days after unprotected sex or up to day 12 of your menstrual cycle. Contact the Sexual Health Helpline for more Effectiveness information. More than 99% Who can use it? Return to Fertility A health professional will take a detailed medical history and pelvic No delay examination to ensure that an IUD is suitable for you. Availability Copper IUDs are suitable for those who: Simple insertion and • are looking for very effective and reliable long-term contraception removal by a health • cannot tolerate hormones due to side effects or other medical conditions professional. -

Plan C: Copper IUD As Emergency Contraception IMPLEMENTATION TOOLKIT for Administrators and Clinicians

Plan C: Copper IUD as Emergency Contraception IMPLEMENTATION TOOLKIT for Administrators and Clinicians March 2016 Developed by TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: OVERVIEW ● Introduction Page 1 ● Background Page 2 ● Who It’s For Page 3 ● How to Use It Page 4 ● Additional Considerations Page 5 SECTION 2: ADMINISTRATIVE ● Pre-Implementation Tools Page 6 1.1 Overview: Plan C 1.2 Checklist: Pre-Implementation 1.3 Staff Buy-in 1.4 Checklist: Policies and Procedures 1.5 Sample: Policies and Procedures 1.6 Marketing Plan C 1.7 Sample: Data Collection Tool SECTION 3: CLINICAL ● Implementation Tools Page 21 2.1 The Facts: The Copper-T as Plan C 2.2 Sample: EC Screening Questionnaire 2.3 Triage Scripts 2.4 Contraceptive Counseling 2.5 Eligibility Flowchart: Plan C 2.6 Checklist: Exam Room Preparation 2.7 Checklist: Client-Centered Approach 2.8 Fact Sheet: Copper IUD Aftercare 2.9 Side Effects Management: Steps in the Delivery of Care 2.10 Side Effects Management: Messages, Assessment & Treatment SECTION 4: ADDITIONAL RESOURCES ● Client Education Material: F.A.Q.’s Page 40 ● Client Education Material: EC Chart Page 42 SECTION 5: REFERENCES Page 44 OVERVIEW Introduction The New York State Center of Excellence for Family Planning and Reproductive Health Services (NYS COE) developed this toolkit to support agencies that receive Title X family planning funding through the New York State Department of Health (NYS DOH) Comprehensive Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Services Program – as well as other sexual and reproductive health service providers – to implement Plan C: Copper IUD as Emergency Contraception (Plan C). -

U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report www.cdc.gov/mmwr Early Release May 28, 2010 / Vol. 59 U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010 Adapted from the World Health Organization Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 4th edition department of health and human services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Early Release CONTENTS The MMWR series of publications is published by the Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Introduction .............................................................................. 1 Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health Methods ................................................................................... 2 and Human Services, Atlanta, GA 30333. How to Use This Document ......................................................... 3 Suggested Citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Title]. MMWR Early Release 2010;59[Date]:[inclusive page numbers]. Using the Categories in Practice ............................................... 3 Recommendations for Use of Contraceptive Methods ................. 4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Contraceptive Method Choice .................................................. 4 Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH Director Contraceptive Method Effectiveness .......................................... 4 Peter A. Briss, MD, MPH Unintended Pregnancy and Increased Health Risk ..................... 4 Acting Associate Director for Science Keeping Guidance Up to Date ................................................... -

Birth Control

Call 311 for Women’s Healthline Free, confidential information and referrals Birth Control New York City Human Resources Administration Infoline Or visit www.nyc.gov/html/hra/pdf/medicaid-offices.pdf What’s Right for You? Information on public health insurance (including Medicaid) for family planning services Other Resources Planned Parenthood of New York City 212-965-7000 or 1-800-230-PLAN (1-800-230-7526) www.ppnyc.org National Women’s Information Center 1-800-994-WOMAN (1-800-994-9662) www.4woman.gov National Family Planning Reproductive Health Association www.nfprha.org Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States www.siecus.org TAKE CONTROL The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Michael R. Bloomberg, Mayor Thomas R. Frieden, M.D., M.P.H., Commissioner nyc.gov/health Contents Why Use Birth Control?................................................. 2 Non-Hormonal Methods Male Condoms............................................................. 4 Female Condoms........................................................... 5 Diaphragms and Cervical Caps............................................. 6 Spermicides................................................................ 7 Copper IUDs (Intrauterine Devices)........................................ 8 Fertility Awareness and Periodic Abstinence............................... 9 Hormonal Methods Birth Control Pills (Oral Contraceptives)...................................10 The Birth Control Patch....................................................12 Vaginal -

Long-Term Safety and Effectiveness of Copper-Releasing Intrauterine Devices: a Case-Study

WHO/RHR/HRP/08.08 UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/WORLD BANK Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) Long-term safety and effectiveness of copper-releasing intrauterine devices: a case-study Reviewer Roberto Rivera Kissimmee, FL, USA With assistance from William Winfrey Futures Institute, Glastonbury, CT, USA for the economic analysis UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP). External evaluation 2003–2007; Long-term safety and effectiveness of copper-releasing intrauterine devices: a case-study. © World Health Organization 2008 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

An Introduction and High Yield Summary of Female Contraceptive

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons HWCOM Faculty Publications Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine 10-24-2017 An Introduction and High Yield Summary of Female Contraceptive Methods Dharam Persaud Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, [email protected] J. Burns Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University J. Trangle Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University J. Agudelo Honors College, Florida International University JA Gonzalez Honors College, Florida International University See next page for additional authors This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/com_facpub Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Dharam; Burns, J.; Trangle, J.; Agudelo, J.; Gonzalez, JA; Nunez, D.; Perez, K.; Rasch, D.; Valencia, S.; and Rao, C. V., "An Introduction and High Yield Summary of Female Contraceptive Methods" (2017). HWCOM Faculty Publications. 117. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/com_facpub/117 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in HWCOM Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Dharam Persaud, J. Burns, J. Trangle, J. Agudelo, JA Gonzalez, D. Nunez, K. Perez, D. Rasch, S. Valencia, and C. V. Rao This article is available at FIU Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/com_facpub/117 Open Access Austin Journal of Reproductive Medicine & Infertility Research Article An Introduction and High Yield Summary of Female Contraceptive Methods Persaud-Sharma D1*, Burns J1, Trangle J1, Agudelo J2, Gonzalez JA2, Nunez D2, Perez K2, Abstract Rasch D2, Valencia S2 and Rao CV1,3 Globally, contraceptive studies and their use are major challenges in the 1Florida International University, Herbert Wertheim realm of public health. -

Long-Acting Reversible Contraception for Adolescents

Review Article Page 1 of 11 Long-acting reversible contraception for adolescents Gina Bravata1, Dilip R. Patel1, Hatim A. Omar2 1Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA; 2Department of Pediatrics and Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Kentucky, Kentucky Children’s Hospital, Lexington, Kentucky, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: DR Patel; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final Approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Dilip R. Patel. Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, 1000 Oakland Drive, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods are the recommended methods for adolescents and young adult women. Etonogestrel subdermal implant, the copper intrauterine device and levonorgestrel intrauterine devices are the currently used LARC methods. LARC methods provide effective contraception by preventing fertilization; however, none has an abortifacient effect. The etonogestrel implant is the most effective method with a Pearl index of 0.05. None of the LARC methods has any adverse effect on bone mineral density. Rare safety concerns associated with intrauterine device use include device expulsion, uterine perforation, pelvic inflammatory disease, and ectopic pregnancy. Fertility resumes rapidly upon discontinuation of LARC method. A number of factors have been shown to be barriers or facilitators of LARC method use by adolescents. This article reviews clinical aspects of use for LARC methods for the primary care medical practitioner. -

Birth Control Basics

FACT SHEET FOR PATIENTS AND FAMILIES Birth Control Basics If you’re sexually active (or you plan to be soon) and don’t want to become pregnant, you’ll need to choose a method of birth control (contraception). There are many different kinds of birth control. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages. To help you choose, this handout presents some basic information and answers some common questions about the most popular forms of birth control. Choosing a method Review this handout with your healthcare provider, keeping these features in mind: • Comfort and ease. Would I feel comfortable using it? Would it be easy to get? Would it be easy for me to use correctly? • Effective. How well does this method work to prevent pregnancy? How concerned am I about sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and does this method help protect against them? Could it be combined with another method to be more effective in preventing pregnancy and STIs? • Safe. Do I have any health conditions, risk factors, Almost half of all pregnancies in the U.S. are or allergies that rule out this option for me? What unintended. To avoid getting pregnant when risks or health benefits might this method provide? you’re not ready, choose a birth control method • Affordable. Can I afford to use this method? Is it that works for your lifestyle and health needs. covered by my medical insurance? Myths and facts and birth control Myth: A woman can’t get pregnant when having sex during her period. Fact: Unprotected sex can lead to pregnancy at any time. -

Intrauterine Contraception

Intrauterine Contraception Jennifer K. Hsia, MD, MPH1 Mitchell D. Creinin, MD1 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California, Address for correspondence JenniferK.Hsia,MD,MPH,Department Sacramento, California of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California, 4860 Y Street, Suite 2500, Sacramento, CA 95817 Semin Reprod Med (e-mail: [email protected]). Abstract Currently, there are only two basic types of intrauterine devices (IUDs): copper and hormonal. However, other types of IUDs are under development, some of which are in clinical trials around the world. Continued development has focused on increasing Keywords efficacy, longer duration of use, and noncontraceptive benefits. This review discusses ► intrauterine device currently available intrauterine contraceptives, such as the Cu380A IUD and levonor- ► levonorgestrel gestrel-releasing intrauterine systems; novel intrauterine contraceptives that are avail- ► copper able in select parts of the world including the intrauterine ball, low-dose copper ► frameless products, frameless devices, and intrauterine delivery systems impregnated with ► indomethacin noncontraceptive medication; and novel products currently in development. History of the Intrauterine Device in the United States removed their IUDs from the market by 1986 due to declining utilization and lawsuits. Only a progesterone-releasing IUD Ancient accounts of stones being placed into the uteri of (Progestasert), first marketed in 1976, remained available. camels to prevent pregnancy during long treks -

Contraceptive Services Only $0 Cost-Share Services, Products and Drugs for Women1,2,3

UnitedHealthcare Contraceptive Services Contraceptive Services Only $0 Cost-share Services, Products and Drugs for Women1,2,3 The health reform law (Affordable Care Act) requires most health plans to pay for birth control (contraceptives and sterilization) for women at no cost to you. Some organizations can choose not to cover birth control (contraceptives) as part of their group health plan for religious reasons. If you are a member of one of these groups (Eligible Organizations), UnitedHealthcare is required to cover certain birth control products and services at no cost to you. You can use your Contraceptive Services Only ID card to get the birth control services, products and drugs on this list for $0 cost-share if they are: • Prescribed by a health care professional such as your doctor. • For services performed by a network health care professional. • For products and drugs filled at a network pharmacy. Medical Birth Control These medical birth control services will be covered at no cost to you when prescribed and performed by a network health care professional. However, birth control products or drugs used as part of these services may be billed at full cost, unless they appear on this list. Medical Birth Control Contraceptive counseling To start, keep or stop the use of birth control services, products and drugs. Place, fit, inspect or remove diaphragms and cervical caps Products must be on page 2 to be no cost. Place, fit, inspect or remove IUDs (intrauterine devices) Mirena®, Skyla™ and Paragard® (copper) IUDs are covered at no cost. Doctors who do not stock the Mirena® and Skyla™ levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems may obtain them through CVS Caremark Specialty Pharmacy at 1-800-237-2767 or Fax 1-800-323-2445. -

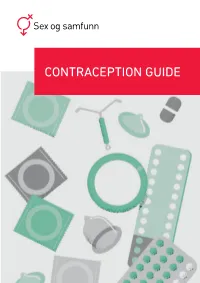

Contraception Guide Contraception Guide Introduction

CONTRACEPTION GUIDE CONTRACEPTION GUIDE INTRODUCTION Since there are many varieties of contraceptives, we have created this brochure to give you an idea of the different types to make it easier for you to make your own informed choice about what contraception is best for you. It helps if you know more about what they contain, how effective and expensive they are, and how long you have to take them for before you choose. It is important to remember that only condoms protect against sexually transmitted infections. Even if you use another method of contraception, we recommend that you use a condom as well if you have sex with a new partner. You can order condoms for free from www.gratiskondomer.no. Find out more about contraception on our website www.sexogsamfunn.no. You can also contact us on the website via our live chat. All the information in this brochure has been quality-controlled by Sex og samfunn and University of Oslo employees. Oslo, March 2018 2 TYPES OF CONTRACEPTIVES NON-HORMONAL CONTRACEPTIVES Find out Duration Type more 5 years Copper IUDs/coils Page 8 Per sexual Condoms Page 10 intercourse HORMONAL CONTRACEPTION CONTAINING PROGESTERONE ONLY Find out Duration Type Brand name more 5 years Hormonal IUDs Mirena, Kyleena Page 12 3 years Hormonal IUDs Levosert, Jaydess 3 years Birth control Nexplanon Page 14 implants 3 months Birth control shot Depo-Provera Page 16 24 hours Progesterone Cerazette, Desogestrel Page 18 pills Orifarm, Conludag HORMONAL CONTRACEPTION CONTAINING OESTROGEN AND PROGESTERONE Find out Duration Type Brand name more 3 weeks Vaginal rings NuvaRing, Ornibel Page 20 1 week Birth control Evra Page 22 patches 24 hours Birth control pills Microgynon, Oralcon, Page 24 Loette, Almina, Synfase, Mercilon, Marvelon, Yasmin, Yasminelle, Yaz, Qlaira, Zoely 3 DIFFERENT TYPES OF CONTRACEPTIVES There are benefits and disadvantages to all contraceptives.