Crazy Rich Asians a Pre-Conference DRAFT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow

CJ7 Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP Public Relations Block Korenbrot PR Sony Pictures Classics Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Judy Chang Leila Guenancia 853 7th Ave, 3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-247-2948 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 1 Short Synopsis: From Stephen Chow, the director and star of Kung Fu Hustle, comes CJ7, a new comedy featuring Chow’s trademark slapstick antics. Ti (Stephen Chow) is a poor father who works all day, everyday at a construction site to make sure his son Dicky Chow (Xu Jian) can attend an elite private school. Despite his father’s good intentions to give his son the opportunities he never had, Dicky, with his dirty and tattered clothes and none of the “cool” toys stands out from his schoolmates like a sore thumb. Ti can’t afford to buy Dicky any expensive toys and goes to the best place he knows to get new stuff for Dicky – the junk yard! While out “shopping” for a new toy for his son, Ti finds a mysterious orb and brings it home for Dicky to play with. To his surprise and disbelief, the orb reveals itself to Dicky as a bizarre “pet” with extraordinary powers. Armed with his “CJ7” Dicky seizes this chance to overcome his poor background and shabby clothes and impress his fellow schoolmates for the first time in his life. -

1 Lisa Funnell. Warrior Women: Gender, Race, and the Transnational Chinese Action Star. New York: SUNY Press, 2014. 294Pp. ISBN1

1 Lisa Funnell. Warrior Women: Gender, Race, and the Transnational Chinese Action Star. New York: SUNY Press, 2014. 294pp. ISBN13: 978-1-4384-5249-4 (hardcover). Warrior Women: Gender, Race and the Transnational Chinese Action Star is a welcome entry into the literature on gender in action film, examining female identity from the perspective of a globalising Chinese identity reflected in its popular culture over the past forty years. Funnell's exploration of the topic takes a historical perspective, looking at female actors in wuxia (martial arts) movies, and in movies which draw on wuxia tropes, from the 1970s through to the early 2000s. One of its unique selling points is that it also takes a transnational view, rather than focusing simply on mainland China, Hong Kong or Taiwan. To this end, it looks at the genre's different iterations in these three areas, and also explores wuxia's entry into global cinema, as diaspora Chinese from Canada and the USA increasingly populate the genre, and as Hollywood borrows tropes and actors from Chinese cinema. The book emphasises that women have been key players in Chinese martial-arts cinema from the very beginning; the genre embodies women differently to men, but this distinctive female embodiment is crucial to the visual language of Chinese martial-arts cinema. This book is particularly valuable in pointing up the transnational nature of wuxia, particularly regarding the boundary-spanning careers of Chinese-Canadian and Chinese-American stars. Significantly, local discourses continue to affect transnational ones, for instance the fact that Canadian actresses tend to downplay their Canadian connections, reflecting the (self-) perception that Canadians are not “interesting” or “exotic” in the way that Americans are, and yet Canada is an increasingly dominant node in the Chinese diaspora. -

Tunneling, Propping, and Expropriation: Evidence from Connected Party Transactions in Hong Kong$

ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Financial Economics 82 (2006) 343–386 www.elsevier.com/locate/jfec Tunneling, propping, and expropriation: evidence from connected party transactions in Hong Kong$ Yan-Leung Cheunga, P. Raghavendra Raub,Ã, Aris Stouraitisc aCity University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China bKrannert Graduate School of Management, Purdue University,403 West State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907-2056, USA cCity University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China Received 9 December 2003; received in revised form 30 June 2004; accepted 2 August 2004 Available online 18 September 2006 Abstract We examine a sample of connected transactions between Hong Kong listed companies and their controlling shareholders. We address three questions: What types of connected transactions lead to expropriation of minority shareholders? Which firms are more likely to expropriate? Does the market anticipate the expropriation by firms? On average, firms announcing connected transactions earn significant negative excess returns, significantly lower than firms announcing similar arm’s length transactions. We find limited evidence that firms undertaking connected transactions trade at discounted valuations prior to the expropriation, suggesting that investors cannot predict expropriation and revalue firms only when expropriation does occur. r 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. JEL classification: G15; G34; K33 Keywords: International corporate governance; Legal -

Asian American Romantic Comedies and Sociopolitical Influences

FROM PRINT TO SCREEN: ASIAN AMERICAN ROMANTIC COMEDIES AND SOCIOPOLITICAL INFLUENCES Karena S. Yu TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 ______________________________ Madhavi Mallapragada, Ph.D. Department of Radio-Television-Film Supervising Professor ______________________________ Chiu-Mi Lai, Ph.D. Department of Asian Studies Second Reader Abstract Author: Karena S. Yu Title: From Print to Screen: Asian American Romantic Comedies and Sociopolitical Influences Supervisor: Madhavi Mallapragada, Ph.D. In this thesis, I examine how sociopolitical contexts and production cultures have affected how original Asian American narrative texts have been adapted into mainstream romantic comedies. I begin by defining several terms used throughout my thesis: race, ethnicity, Asian American, and humor/comedy. Then, I give a history of Asian American media portrayals, as these earlier images have profoundly affected the ways in which Asian Americans are seen in media today. Finally, I compare the adaptation of humor in two case studies, Flower Drum Song (1961) which was created by Rodgers and Hammerstein, and Crazy Rich Asians (2018) which was directed by Jon M. Chu. From this analysis, I argue that both seek to undercut the perpetual foreigner myth, but the difference in sociocultural incentives and control of production have resulted in more nuanced portrayals of some Asian Americans in the latter case. However, its tendency to push towards the mainstream has limited its ability to challenge stereotyped representations, and it continues to privilege an Americentric perspective. 2 Acknowledgements I owe this thesis to the support and love of many people. To Dr. Mallapragada, thank you for helping me shape my topic through both your class and our meetings. -

Chinese Ethnic Branding Strategies and the Roles of Language in the Movie Crazy Rich Asians

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI CHINESE ETHNIC BRANDING STRATEGIES AND THE ROLES OF LANGUAGE IN THE MOVIE CRAZY RICH ASIANS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Program in English Language Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Magister Humaniora (M.Hum) in English Language Studies By Fennie Karline Rosario Tenau Student Number: 186332004 THE GRADUATE PROGRAM OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2020 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI “ He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the human heart, yet no one can find out what God has done from beginning to end.” - Ecclesiastes 3:11- I dedicated this Thesis to My angel mother, Margaretha Warayaan. iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ABSTRACT Tenau, Fennie Karline Rosario. 2020. Chinese Ethnic Branding Strategies and The Roles of Language in The Movie Crazy Rich Asians. Yogyakarta: English Language Studies. Graduate Program. Sanata Dharma University. Chinese attempt to show their existence in the world‘s eyes can be seen in their branding. Branding is important in the aspect of ethnicity because it creates certain assumptions about an ethnic group. They try to show their identity by using several strategies both in explicit and implicit ways. However, Chinese themselves barely participate in Hollywood movies as the main characters. Crazy Rich Asians then appears as a movie that highlights the real-life portrayal of Chinese and diaspora in real life. Much of the plot conflict focuses on the Eastern- educated family welcoming Rachel, a Chinese-American as a part of them. Most of the main characters classify themselves as culturally Chinese, so they are playing Chinese ethnicity characters. -

Gender Trouble in Hongkong Cinema Tammy Cheung Et Michael Gilson

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 10:00 Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies Gender Trouble in Hongkong Cinema Tammy Cheung et Michael Gilson Le nouveau cinéma chinois Résumé de l'article Volume 3, numéro 2-3, printemps 1993 Cet article fait le point sur le cinéma contemporain de Hongkong en se penchant plus particulièrement sur des questions entourant les URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1001198ar représentations de personnages féminins et masculins. Les films, la société et DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1001198ar la culture du Hongkong d’aujourd’hui commencent à peine à s’intéresser à la réalité gaie et lesbienne, et, dans une certaine mesure, au féminisme. Comment Aller au sommaire du numéro les différents types de personnages féminins sont-ils présentés dans le cinéma contemporain de Hongkong? Comment le concept traditionnel chinois de « mâle » diffère-t-il de celui que nous connaissons en Occident? La popularité récente de personnages transsexuels dans plusieurs films est aussi examinée. Éditeur(s) Les auteurs soutiennent que des représentations stéréotypées de personnages Cinémas féminins, masculins et homosexuels prédominent dans l’industrie cinématographique de Hongkong et que les représentations positives de gais et de lesbiennes y sont le plus souvent absentes. ISSN 1181-6945 (imprimé) 1705-6500 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Cheung, T. & Gilson, M. (1993). Gender Trouble in Hongkong Cinema. Cinémas, 3(2-3), 181–201. https://doi.org/10.7202/1001198ar Tous droits réservés © Cinémas, 1993 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Reading Ambiguity and Ambivalence: the Asymmetric Structure of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Felicia Chan, University of Nottingham, UK

Reading Ambiguity and Ambivalence: The Asymmetric Structure of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Felicia Chan, University of Nottingham, UK Bordwell and Thompson write that: "Looking is purposeful; what we look at is guided by our assumptions and expectations about what to look for" (Bordwell and Thompson, 1990: 141). Bordwell and Thompson's statement about what they refer to as "film art" resonates against the remarkable variety of responses to Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) from various media. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, for instance, calls the film, "the most exhilarating martial arts movie I have seen", while a Beijing newspaper describes it "as unrealistic and exaggerated as a video game" (Ebert quoted in Chu, 2001: A1: 1). The opening fight sequence, which has the actors flying across rooftops, is widely reported to have produced spontaneous applause at its Cannes Film Festival screening; in Shanghai, however, "audiences hissed its fantasy flight scenes" (Rennie, 2001: 30). Hong Kong viewer, Maria Wong, says: For Hong Kong Chinese there's simply not enough action… I grew up with this type of film. You can see them everyday on TV. It's nothing new, even the female angle. But Crouching Tiger is so slow, it's a bit like listening to grandma telling stories. (Wong quoted in Rose, 2001) The first chase sequence does indeed take place about fifteen or twenty minutes into the film -- far too late by Hong Kong standards. In contrast, many Western critics have praised its gravity-defying stunts. For instance, CNN.com reviewer, Paul Tatara gushes: "The first fight, which springs to sudden, exquisite life… surely will elicit rounds of applause from audiences the world over -- action, after all, has become cinema's universal language" (Tatara, 2000). -

FN DP WEB.Indd

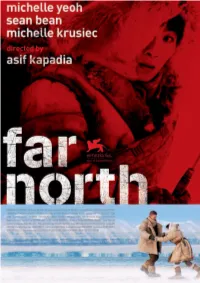

INGENIOUS FILM PARTNERS FILM4 AND CELLULOID DREAMS PRESENT A PRODUCTION FROM THE BUREAU IN CO PRODUCTION WITH LE BUREAU AND PJB PICTURE COMPANY AND FILM CAMP AND NATIXIS COFICINE IN ASSOCIATION WITH SOFICINEMA AND COFINOVA AN ASIF KAPADIA FILM FAR NORTH MICHELLE YEOH SEAN BEAN MICHELLE KRUSIEC France/UK – 2007 - 89 min – Colour - Dolby SRD – Scope WORLD SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS CELLULOID DREAMS PREMIER PR PARIS IN VENICE 2 rue Turgot Liz Miller: 75009 Paris, France +39 335 671 3185 T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 [email protected] F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 [email protected] Ginger Corbett: +39 334 632 4806 www.celluloid-dreams.com [email protected] SYNOPSIS FAR NORTH is a dark and tragic epic thriller about the battle for survival. Revenge, jealousy and courage are played out against the harsh beauty of the desolate Arctic tundra. SAIVA, a woman living under a curse, and ANJA, her adopted daughter, live in a remote land far from civilization where she believes they will be safe. Saiva is the sole survivor of an indigenous tribe of reindeer herders slaughtered by a troop of marau- ding soldiers. After the massacre, Saiva leads the men to their death on a glacier avenging Ivar, the only man she ever loved. They struggle to survive, living off the scarce prey they can kill. One day a figure appears on the horizon and collapses. Despite her fears and doubts Saiva takes him in and nurses him back from the brink of death. Loki the fugitive, recovers and settles in with the two women as the snow arrives and the long winter nights close in. -

Learner-Centered Activities from the DVD-Format" Crouching Tiger

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 466 097 FL 027 354 AUTHOR Lin, Li-Yun TITLE Learner-Centered Activities from the DVD-Format "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon." PUB DATE 2001-11-00 NOTE 13p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS College Students; *English (Second Language); *Films; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Listening Skills; Oral Language; Second Language Instruction; Second Language Learning; Skill Development; *Student Motivation; *Student Participation; Teacher Student Relationship; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Learner Centered Instruction; Taiwanese People ABSTRACT This paper demonstrates how Taiwanese English-as-a-Second-Language (ESL) college teachers and students collaborate and negotiate to design various learner-centered activities based on the Chinese film, "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon." These activities are intended to enhance students' listening and speaking abilities. The paperdemonstrates eight classroom activities, including the following: repeated viewing with various subtitles, viewing with reversed subtitles, viewing with commentary, an interview with actor Michelle Yeoh (who is not anative speaker of English but speaks quite well), sequencing, interior monologue, a translation competition game, and theme song singing. The paper demonstrates how a Chinese film in the DVD format can be a highly motivating teaching material for Chinese ESL college students. It also highlights how students' learning motivation and effectiveness can be significantly enhanced if they participate in the process of selecting materials and designing activities. The paper discusses both the technical utilization of DVD and guidelines for implementing the learner-centered approach for each activity, focusing on teacher and student roles. Three appendixes present English learning activities. (Contains 11 references.) (SM) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Creative Encounters Working Papers 11

The Simultaneous Success and Disappearance of Hong Kong Martial Arts Film Analysed through costume and movement in 'Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon' Skov, Lise Document Version Final published version Publication date: 2008 License CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Skov, L. (2008). The Simultaneous Success and Disappearance of Hong Kong Martial Arts Film: Analysed through costume and movement in 'Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon'. imagine.. CBS. Creative Encounters Working Paper No. 11 Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Creativity at Work: The simultaneous success and disappearance of Hong Kong martial arts film - analysed through costume and movement in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon By Lise Skov February 2008 Page 1 of 7 Creative Encounters Working Papers #11 Abstract Keywords Author Lise Skov is Associate Professor in the Department of Intercultural Communication and Management at the Copenhagen Business School, Denmark. She may be reached by e-mail at [email protected] Page 2 of 7 Creative Encou7nters Working Paper # 11 The simultaneous success and disappearance of Hong Kong martial arts film, analysed through costume and movement in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon In this essay, I wish to examine the relation between body, movement and costume in Chinese martial arts film. -

Hong Kong Martial Arts Films

GENDER, IDENTITY AND INFLUENCE: HONG KONG MARTIAL ARTS FILMS Gilbert Gerard Castillo, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2002 Approved: Donald E. Staples, Major Professor Harry Benshoff, Committee Member Harold Tanner, Committee Member Ben Levin, Graduate Coordinator of the Department of Radio, TV and Film Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, TV and Film C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Castillo, Gilbert Gerard, Gender, Identity, and Influence: Hong Kong Martial Arts Films. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), December 2002, 78 pp., references, 64 titles. This project is an examination of the Hong Kong film industry, focusing on the years leading up to the handover of Hong Kong to communist China. The influence of classical Chinese culture on gender representation in martial arts films is examined in order to formulate an understanding of how these films use gender issues to negotiate a sense of cultural identity in the face of unprecedented political change. In particular, the films of Hong Kong action stars Michelle Yeoh and Brigitte Lin are studied within a feminist and cultural studies framework for indications of identity formation through the highlighting of gender issues. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank the members of my committee all of whom gave me valuable suggestions and insights. I would also like to extend a special thank you to Dr. Staples who never failed to give me encouragement and always made me feel like a valuable member of our academic community. -

Diasporic Narratives and Global Asia a Dissertation

CAPITALIZING RACE: DIASPORIC NARRATIVES AND GLOBAL ASIA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY YUAN DING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIERMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ADVISOR: JOSEPHINE LEE August 2019 © Yuan Ding, 2019 Acknowledgements My sincerest gratitude goes to my dissertation advisor, Josephine Lee, who can always be counted on for prompt feedback on edits, and responses to last-minute requests for signatures, letters, and emergency meetings. Without her gentle urging and patient guidance, I would not have been able to finish this dissertation on time. Her tutelage, kind yet firm, has become a model I strive to achieve in my own advising and mentoring practice. I would also like to thank my other dissertation committee members, Jani Scandura, Jigna Desai and Shevvy Craig, who have read and critiqued this work in its various inchoate forms, and offered invaluable suggestions for revision. This dissertation is finished with the generous support of the Guangzhou Fellowship offered by the English Department, as well as the University’s Graduate Research Partnership Program Fellowship, which granted me the opportunity to take a year and two summers off teaching, to devote fully to research and writing. My loving gratitude goes to those who offered counsel, friendship, encouragement and a shoulder to cry on when things got tough. I’m thinking especially of Na-Rae Kim, Eunha Na, Thea Sircar and Bomi Yoon, who had been my writing partners at different stages of the writing process. I’m enormously grateful for the countless hours spent in their quiet companionship.