The Signification of Operatic Mode of Utterance in Sergey Prokofiev's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (/prɵˈkɒfiɛv/; Russian: Сергей Сергеевич Прокофьев, tr. Sergej Sergeevič Prokof'ev; April 27, 1891 [O.S. 15 April];– March 5, 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor. As the creator of acknowledged masterpieces across numerous musical genres, he is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. His works include such widely heard works as the March from The Love for Three Oranges, the suite Lieutenant Kijé, the ballet Romeo and Juliet – from which "Dance of the Knights" is taken – and Peter and the Wolf. Of the established forms and genres in which he worked, he created – excluding juvenilia – seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, and nine completed piano sonatas. A graduate of the St Petersburg Conservatory, Prokofiev initially made his name as an iconoclastic composer-pianist, achieving notoriety with a series of ferociously dissonant and virtuosic works for his instrument, including his first two piano concertos. In 1915 Prokofiev made a decisive break from the standard composer-pianist category with his orchestral Scythian Suite, compiled from music originally composed for a ballet commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev commissioned three further ballets from Prokofiev – Chout, Le pas d'acier and The Prodigal Son – which at the time of their original production all caused a sensation among both critics and colleagues. Prokofiev's greatest interest, however, was opera, and he composed several works in that genre, including The Gambler and The Fiery Angel. Prokofiev's one operatic success during his lifetime was The Love for Three Oranges, composed for the Chicago Opera and subsequently performed over the following decade in Europe and Russia. -

BETROTHAL in a MONASTERY Stephan Rügamer

SERGEI PROKOFIEV BETROTHAL IN A MONASTERY Stephan Rügamer . Andrei Zhilikhovsky . Aida Garifullina Violeta Urmana . Bogdan Volkov Conducted by Daniel Barenboim . Staged by Dmitri Tcherniakov SERGEI PROKOFIEV BETROTHAL IN A MONASTERY At the Staatsoper Unter den Linden Dmitri Tcherniakov stages Prokofiev’s lyrical comic opera Betrothal in a Monastery under Orchestra Staatskapelle Berlin Daniel Barenboim’s baton. Though composed in wartime Soviet Conductor Daniel Barenboim Russia, the plot is a non political classic comedy of errors based Choir Staatsopernchor Berlin Chorus Master Martin Wright on Richard Sheridan’s 18th-century play The Duenna about two Stage Director Dmitri Tcherniakov young couples who want to come together and an old man who wants to prevent this – and all kinds of confusion and misunder- Don Jerome Stephan Rügamer standings. Russian director Tcherniakov recasts the complete Don Ferdinand Andrei Zhilikhovsky Luisa Aida Garifullina opera as therapeutic role play for “Opera-Addict Anonymus”. The Duenna Violeta Urmana Daniel Barenboim conducts the Staatskapelle Berlin and “the Don Antonio Bogdan Volkov uniformly excellent cast” (Financial Times). Aida Garifullina “who Clara d‘Almanza Anna Goryachova Mendoza Goran Jurić did not have to shy away from the musical comparison with the Don Carlos Lauri Vasar young Anna Netrebko” impresses with her “highly attractive, Host Maxim Paster slightly darkened timbre”, Bogdan Volkov is “an ideal Don Antonio, Video Director Andy Summer an elegantly phrasing Iyric tenor” and Stephan Rügamer shines with his “characteristic tenor voice” (Opernglas). “Musically this Length: 168' performance is a celebration in every sense” applauds BR Klassik. Shot in HDTV 1080/50i Cat. no. A 050 50684 A co-production of Bel Air Media, Mezzo, Staatsoper unter den Linden and UNITEL World Sales: All rights reserved · credits not contractual · Different territories · Photos: © MartinWalz · Flyer: mmessner.de Unitel GmbH & Co. -

Season 2013-2014

23 Season 2013-2014 Thursday, February 13, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, February 14, at 8:00 Saturday, February 15, at 8:00 Vladimir Jurowski Conductor Vsevolod Grivnov Tenor Alexey Zuev Piano Sherman Howard Speaker Tatiana Monogarova Soprano Sergei Leiferkus Baritone Westminster Symphonic Choir Joe Miller Director Rachmaninoff/ Songs orch. Jurowski I. “Christ Is Risen,” Op. 26, No. 6 II. “Dreams,” Op. 38, No. 5 III. “The Morn of Life,” Op. 34, No. 10 IV. “So Dread a Fate,” Op. 34, No. 7 V. “All Things Depart,” Op. 26, No. 15 VI. “Come Let Us Rest,” Op. 26, No. 3 VII. “Before My Window,” Op. 26, No. 10 VIII. “The Little Island,” Op. 14, No. 2 IX. “How Fair this Spot,” Op. 21, No. 7 X. “What Wealth of Rapture,” Op. 34, No. 12 (U.S. premiere of orchestrated version) Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 4 in G minor, Op. 40 I. Allegro vivace II. Largo III. Allegro vivace Intermission 24 Rachmaninoff The Bells, Op. 35 I. Allegro, ma non tanto II. Lento—Adagio III. Presto—Prestissimo IV. Lento lugubre—Allegro—Andante— Tempo I This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. These concerts are presented in cooperation with the Sergei Rachmaninoff Foundation. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 3 Story Title 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra community itself. His concerts to perform in China, in 1973 is one of the preeminent of diverse repertoire attract at the request of President orchestras in the world, sold-out houses, and he has Nixon, today The Philadelphia renowned for its distinctive established a regular forum Orchestra boasts a new sound, desired for its for connecting with concert- partnership with the National keen ability to capture the goers through Post-Concert Centre for the Performing hearts and imaginations of Conversations. -

Dramatic Musical Versions of Dostoevsky: Sergei Prokopev's the Gambler

DRAMATIC MUSICAL VERSIONS OF DOSTOEVSKY: SERGEI PROKOPEV'S THE GAMBLER by Vladimir Seduro * I The Russian composer Sergei Sergeevich Prokof'ev (1891-1953) stands as a pioneer in the creation of large operatic works based on Dostoevsky. The composer Nikolai Iakovlevich Miaskovskii (1881-1950) also dreamed of an opera based on Dostoevsky. While working on his operatic version of The Idiot, Miaskovskii even considered to whom he would assign the roles of Nastas'ia Filip- povna and Aglaia. He first conceived the part of Nastas'ia for the actress V. N. Petrova-Zvantseva, and he had the singer E. V. Kono- sova-Derzhanovskaia in mind for the role of Aglaia Epanchina. But his constant directorial and teaching duties and the distraction of his symphonic work absorbed his attention and his energies in other musical activities. But the idea of basing an opera on Dostoevsky's The Gambler was realized before the Revolution in Russia. It is true that before Prokof'ev there was a Russian opera based on Dostoevsky's story «The Little Boy at Christ's Christmas Tree.» The opera The Christmas Tree [«Yolka»] by Vladimir Rebikov was produced in 1903 at the Moscow «Aquarium» Theatre nm by M. E. Medvedev, and in 1906 it saw the footlights of theaters in Prague, Brno, and Berlin. But the contents of The Christmas Tree were only indirectly linked to Dostoevsky's story. Rebikov's one act, three scene opera joined the theme of Dostoevsky's story to the plot of Hans Christian Andersen's story «The Girl with the * Dr. Vladimir Seduro, Professor of Russian at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, is the author of several books, the most recent of which are Dostoevski's Image in Russia Today (Nordland, 1975) and Dostoevski in Russian Emigre Criticism (Nordland, 1975). -

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich)

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich) (b Sontsovka, Bakhmutsk region, Yekaterinoslav district, Ukraine, 11/23 April 1891; d Moscow, 5 March 1953). Russian composer and pianist. He began his career as a composer while still a student, and so had a deep investment in Russian Romantic traditions – even if he was pushing those traditions to a point of exacerbation and caricature – before he began to encounter, and contribute to, various kinds of modernism in the second decade of the new century. Like many artists, he left his country directly after the October Revolution; he was the only composer to return, nearly 20 years later. His inner traditionalism, coupled with the neo-classicism he had helped invent, now made it possible for him to play a leading role in Soviet culture, to whose demands for political engagement, utility and simplicity he responded with prodigious creative energy. In his last years, however, official encouragement turned into persecution, and his musical voice understandably faltered. 1. Russia, 1891–1918. 2. USA, 1918–22. 3. Europe, 1922–36. 4. The USSR, 1936–53. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY DOROTHEA REDEPENNING © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online 1. Russia, 1891–1918. (i) Childhood and early works. (ii) Conservatory studies and first public appearances. (iii) The path to emigration. © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online Prokofiev, Sergey, §1: Russia: 1891–1918 (i) Childhood and early works. Prokofiev grew up in comfortable circumstances. His father Sergey Alekseyevich Prokofiev was an agronomist and managed the estate of Sontsovka, where he had gone to live in 1878 with his wife Mariya Zitkova, a well-educated woman with a feeling for the arts. -

Burdenko, Roman - Baritone

Burdenko, Roman - Baritone Biography Roman Burdenko is one of the most interesting young baritones. He is the winner of many prestigious singing competitions including Competizione dell’ Opera International Competition in Moscow (1st Prize, 2011), Concours de Chant Lyrique Long-Thibaud-Crespin in Paris (2nd Prize, 2011), Placido Domingo’s Operalia in Beijing (3rd Prize, 2012), and 32nd International Hans Gabor Belvedere Singing Competition in Amsterdam (2nd Prize, 2013). Burdenko joined Mariinsky Opera Company in Sankt-Petersburg in 2017. Among his recent and upcoming engagements are Shchelkalov (Boris Godunov) at the Grand Théâtre de Genève, Gerrard (Andrea Chenier) in Deutsche Oper Berlin, Rodrigo (Don Carlo) in Bolshoi Theatre, Lord Enrico Ashton (Lucia di Lammermoor) at Zurich Opera, Alfio (Cavalleria rusticana) and Tonio (I pagliacci) at the Dutch National Opera, also Rigoletto, Prince Igor, Falstaff, Alberich (Das Rheingold), Amorasro (Aida), Rangoni (Boris Godunov), Escamillo (Carmen), Tonio (I pagliacci), Tomsky (The Queen of Spades) and Albiani (Simon Boccanegra) at Mariinsky. Among highlights of his previous seasons are roles of Tonio (I pagliecci), Alfio (Cavalleria Rusticana), Rangoni (Boris Godunov) at Teatro Municipal de Santiago de Chile, Marcello (La bohème) at the Komische Oper Berlin, Enrico (Lucia di Lammermoor) at the Palm Beach Opera, Paolo Albiani (Simon Boccanegra) at theTeatro Municipal de Santiago de Chile and Opéra national du Rhin in Strasbourg. During past seasons Burdenko has performed Tonio, Prince Igor, Stankar (Stiffelio), Dunois (Orleanskaya deva), Renato (Un ballo), Enrico (Lucia), Ford (Falstaff)and debuted in Prokofiev’s Ivan the Terrible at the Rotterndam Gergiev Festival among many others. He sung on stages of most prestigous theatres such as Théâtre de Genève, Bolshoi Theatre, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Las Palmas Opera, Opernhaus Zurich, Glyndebourne Festval, Royal Danish Opera Copenhagen, Bavarian State Opera etc. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1983

. ^ 5^^ mar9 E^ ^"l^Hifi imSSii^*^^ ' •H-.-..-. 1 '1 i 1^ «^^«i»^^^m^ ^ "^^^^^. Llii:^^^ %^?W. ^ltm-''^4 j;4W»HH|K,tf.''if :**.. .^l^^- ^-?«^g?^5?,^^^^ _ '^ ** '.' *^*'^V^ - 1 jV^^ii 5 '|>5|. * .««8W!g^4sMi^^ -\.J1L Majestic pine lined drives, rambling elegant mfenor h^^, meandering lawns and gardens, velvet green mountain *4%ta! canoeing ponds and Laurel Lake. Two -hundred acres of the and present tastefully mingled. Afulfillment of every vacation delight . executive conference fancy . and elegant home dream. A choice for a day ... a month . a year. Savor the cuisine, entertainment in the lounges, horseback, sleigh, and carriage rides, health spa, tennis, swimming, fishing, skiing, golf The great estate tradition is at your fingertips, and we await you graciously with information on how to be part of the Foxhollow experience. Foxhollow . an tver growing select family. Offerings in: Vacation Homes, Time- Shared Villas, Conference Center. Route 7, Lenox, Massachusetts 01240 413-637-2000 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor One Hundred and Second Season, 1982-83 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Abram T. Collier, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Leo L. Beranek, Vice-President George H. Kidder, Vice-President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick William J. Poorvu J. P. Barger Mrs. John L. Grandin Irving W. Rabb Mrs. John M. Bradley David G. Mugar Mrs. George R. Rowland Mrs. Norman L. Cahners Albert L. Nickerson Mrs. George Lee Sargent George H.A. -

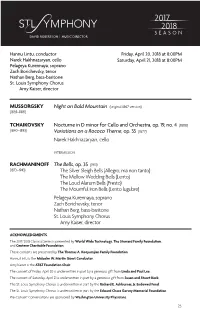

Night on Bald Mountain (Original 1867 Version) (1839–1881)

2017 2018 SEASON Hannu Lintu, conductor Friday, April 20, 2018 at 8:00PM Narek Hakhnazaryan, cello Saturday, April 21, 2018 at 8:00PM Pelageya Kurennaya, soprano Zach Borichevsky, tenor Nathan Berg, bass-baritone St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director MUSSORGSKY Night on Bald Mountain (original 1867 version) (1839–1881) TCHAIKOVSKY Nocturne in D minor for Cello and Orchestra, op. 19, no. 4 (1888) (1840–1893) Variations on a Rococo Theme, op. 33 (1877) Narek Hakhnazaryan, cello INTERMISSION RACHMANINOFF The Bells, op. 35 (1913) (1873–1943) The Silver Sleigh Bells (Allegro, ma non tanto) The Mellow Wedding Bells (Lento) The Loud Alarum Bells (Presto) The Mournful Iron Bells (Lento lugubre) Pelageya Kurennaya, soprano Zach Borichevsky, tenor Nathan Berg, bass-baritone St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The 2017/2018 Classical Series is presented by World Wide Technology, The Steward Family Foundation, and Centene Charitable Foundation. These concerts are presented by The Thomas A. Kooyumjian Family Foundation. Hannu Lintu is the Malcolm W. Martin Guest Conductor. Amy Kaiser is the AT&T Foundation Chair. The concert of Friday, April 20 is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Linda and Paul Lee. The concert of Saturday, April 21 is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Susan and Stuart Keck. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Richard E. Ashburner, Jr. Endowed Fund. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Edward Chase Garvey Memorial Foundation. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. 23 RUSSIAN ORIGINALS BY RENÉ SPENCER SALLER TIMELINKS “My music is the product of my temperament, and so it is Russian music,” Serge Rachmaninoff declared. -

Prokofiev's Soviet Operas Nathan Seinen Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-46079-9 — Prokofiev's Soviet Operas Nathan Seinen Frontmatter More Information Prokofiev’s Soviet Operas Prokofiev considered himself to be primarily a composer of opera, and his return to Russia in the mid 1930s was partially motivated by the goal to renew his activity in this genre. His Soviet career coincided with the height of the Stalin era, when official interest and involvement in opera increased, leading to demands for nationalism and heroism to be represented on the stage in order to promote the Soviet Union and the Stalinist regime. Drawing on a wealth of primary source materials and engaging with recent scholarship in Slavonic studies, this book investigates encounters between Prokofiev’s late operas and the aesthetics of socialist realism, contemporary culture (including literature, film, and theatre), political ideology, and the obstacles of bureaucratic interventions and historical events. This contextual approach is interwoven with critical interpretations of the operas in their original versions, providing a new account of their stylistic and formal features and connections to operatic traditions. nathan seinen is Assistant Professor of Musicology at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-46079-9 — Prokofiev's Soviet Operas Nathan Seinen Frontmatter More Information Music Since 1900 general editor Arnold Whittall This series – formerly Music in the Twentieth Century – offers a wide perspective on music and musical life since the end of the nineteenth century. Books included range from historical and biographical studies concentrating particularly on the context and circumstances in which composers were writing, to analytical and critical studies concerned with the nature of musical language and questions of compositional process. -

![Prokofiev [Prokof’Yev; Prokofieff], Sergey [Serge] (Sergeyevich)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5208/prokofiev-prokof-yev-prokofieff-sergey-serge-sergeyevich-4325208.webp)

Prokofiev [Prokof’Yev; Prokofieff], Sergey [Serge] (Sergeyevich)

Prokofiev [Prokof’yev; Prokofieff], Sergey [Serge] (Sergeyevich) (b Sontsovka, Bakhmut district, Yekaterinoslav gubeniya [now Krasnoye, Selidovsky district, Donetsk region, Ukraine], 15/27 April 1891; d Moscow, 5 March 1953). Russian composer. 1. Pre-Soviet period. 2. The 1930s. 3. The 1940s. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY RICHARD TARUSKIN © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online Prokofiev, Sergey 1. Pre-Soviet period. Prokofiev‟s operatic career began at the age of eight (with Velikan, „The Giant‟, a 12-page opera in three acts), and he always saw himself first and foremost as a composer of music for the lyric stage. If this seems surprising, it is not only because of Prokofiev‟s great success in the realm of instrumental concert music but also because of the singularly unlucky fate of his operas. Of the seven he completed, he saw only four produced; of the four, only two survived their initial production; and of the two, only one really entered the repertory. As usual in such cases, the victim has been blamed: „Through all his writings about opera there runs a streak of loose thinking and naivety‟, wrote one critic, „and it runs through the works, too‟. That – plus a revolution, a world war and a repressive totalitarian regime whose unfathomable vagaries the composer could never second-guess – indeed made for a frustrating career. Yet time has begun to vindicate some of those long-suffering works, and we may be glad that despite everything (and unlike Shostakovich) Prokofiev persisted as an operatic composer practically to the end. The charge of „naivety‟ derives from Prokofiev‟s life-long commitment to what might be called the traditions of Russian operatic radicalism. -

Sergei Prokofiev: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

SERGEI PROKOFIEV: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1902: Symphony in G 1908: Symphony “No.2” in E minor 1909-14/29: Sinfonietta in A major, op.5/48: 20 minutes 1909-10: Two Poems for female chorus and orchestra, op. 7: 9 minutes 1910: Symphonic Poem “Dreams”, op.6: 11 minutes 1910-14/34: Symphonic Sketch “Autumnal”, op.8: 7 minutes 1911-12: Piano Concerto No.1 in D flat major, op.10: 16 minutes 1912-13: Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, op.16: 34 minutes 1912-14: Suite “Moments and Sarcasm” for orchestra, op.17B 1914: “The Ugly Duckling” for soprano and orchestra, op.18A: 12 minutes 1914-15: “Scythian Suite”(“Ala et Lolly”) for orchestra, op.20: 20 minutes (and Ballet, op.20A) 1915-17: Violin Concerto No.1 in D major, op.19: 22 minutes 1915/20: Ballet “Chout”, op.21: 57 minutes (and Ballet Suite, op. 21B) 1915-17: “Visions fugitives” for orchestra, op.22A: 22 minutes 1915-17/ 27-28/31: Symphonic Suite “Four Portraits from the Opera ‘The Gambler’” for orchestra, op.49: 23 minutes 1916-17: Symphony No.1 “Classical” in D major, op.25: 14 minutes 1917-21: Piano Concerto No.3 in C major, op.26: 30 minutes 1917/34: Andante for orchestra, op. 29B: 8 minutes 1917-18: Cantata “Seven, they are seven” for tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.30: 7 minutes 1919/24: Symphonic Suite “The Love of Three Oranges” for orchestra, op.33B 1919/34: Overture on Hebrew Themes, op. 34B: 10 minutes 1921-23: Suite from the Opera “The Fiery Angel” for voice and orchestra, op.