Ornitholgy-Def-LR-Def.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Spain: the Europe Introtour April 2019

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southern Spain: The Europe Introtour April 2019 A Tropical Birding set departure tour SOUTHERN SPAIN: The Europe Introtour 1st – 9th April 2019 Tour Leader: Emma Juxon All photographs in this report were taken by Emma Juxon unless otherwise stated, species depicted in photographs are named in BOLD RED www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southern Spain: The Europe Introtour April 2019 Introduction For European birders, there is nowhere better to take a birding trip than the Iberian Peninsula. A region largely overlooked by North American birders in the past, it boasts some of THE best birding on the continent, it’s certainly not to be missed. We visit the outstanding regions of Extremadura and Andalucía on this tour, making our way through breathtaking mountainous landscapes, through rolling steppes and spectacular marismas. With many participants visiting the Old World for the first time, it promises a wealth of lifers, great food, fantastic people and an easy-going introduction to the Mediterranean way of life. One of the many beauties of this tour is that we only have two bases. Starting in Madrid, we make our way through the beautiful Spanish countryside, passing vineyards and castillos to get to wildflower- carpeted Extremadura. Here we enjoy the Belen Steppe, Caceres Plains and the exceptional Monfragüe National Park, encountering incredible birds such as Eurasian Griffon, Pin-tailed Sandgrouse, Great Bustard and Iberian Magpie. From here we head south to our next base in the picturesque pilgrimage town of El Rocío; I love this charming place, with its sandy roads, wonderful bird-filled marshes and charismatic people. -

2015-Birds-Of-ML1.Pdf

FREE presents Birds of Mawson Lakes Linda Vining & MikeBIRDS Flynn of Mawson Lakes An online book available at www.mawsonlakesliving.info Republished as an ebook in 2015 First Published in 2013 Published by Mawson Lakes Living Magazine 43 Parkview Drive Mawson Lakes 5095 SOUTH AUSTRALIA Ph: +61 8 8260 7077 [email protected] www.mawsonlakesliving.info Photography and words by Mike Flynn Cover: New Holland Honeyeater. See page 22 for description © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without credit to the publisher. BIRDS inof MawsonMawson LakesLakes 3 Introduction What bird is that? Birdlife in Mawson Lakes is abundant and adds a wonderful dimension to our natural environment. Next time you go outside just listen to the sounds around you. The air is always filled with bird song. Birds bring great pleasure to the people of Mawson Lakes. There is nothing more arresting than a mother bird and her chicks swimming on the lakes in the spring. What a show stopper. The huge variety of birds provides magnificent opportunities for photographers. One of these is amateur photographer Mike Flynn who lives at Shearwater. Since coming to live at Mawson Lakes he has become an avid bird watcher and photographer. I often hear people ask: “What bird is that?” This book, brought to you by Mawson Lakes Living, is designed to answer this question by identifying birds commonly seen in Mawson Lakes and providing basic information on where to find them, what they eat and their distinctive features. -

Bird Species I Have Seen World List

bird species I have seen U.K tally: 279 US tally: 393 Total world: 1,496 world list 1. Abyssinian ground hornbill 2. Abyssinian longclaw 3. Abyssinian white-eye 4. Acorn woodpecker 5. African black-headed oriole 6. African drongo 7. African fish-eagle 8. African harrier-hawk 9. African hawk-eagle 10. African mourning dove 11. African palm swift 12. African paradise flycatcher 13. African paradise monarch 14. African pied wagtail 15. African rook 16. African white-backed vulture 17. Agami heron 18. Alexandrine parakeet 19. Amazon kingfisher 20. American avocet 21. American bittern 22. American black duck 23. American cliff swallow 24. American coot 25. American crow 26. American dipper 27. American flamingo 28. American golden plover 29. American goldfinch 30. American kestrel 31. American mag 32. American oystercatcher 33. American pipit 34. American pygmy kingfisher 35. American redstart 36. American robin 37. American swallow-tailed kite 38. American tree sparrow 39. American white pelican 40. American wigeon 41. Ancient murrelet 42. Andean avocet 43. Andean condor 44. Andean flamingo 45. Andean gull 46. Andean negrito 47. Andean swift 48. Anhinga 49. Antillean crested hummingbird 50. Antillean euphonia 51. Antillean mango 52. Antillean nighthawk 53. Antillean palm-swift 54. Aplomado falcon 55. Arabian bustard 56. Arcadian flycatcher 57. Arctic redpoll 58. Arctic skua 59. Arctic tern 60. Armenian gull 61. Arrow-headed warbler 62. Ash-throated flycatcher 63. Ashy-headed goose 64. Ashy-headed laughing thrush (endemic) 65. Asian black bulbul 66. Asian openbill 67. Asian palm-swift 68. Asian paradise flycatcher 69. Asian woolly-necked stork 70. -

Calibrating Sentinel-2 Imagery with Multispectral UAV Derived

drones Article Calibrating Sentinel-2 Imagery with Multispectral UAV Derived Information to Quantify Damages in Mediterranean Rice Crops Caused by Western Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio) Magda Pla 1,* , Gerard Bota 1 , Andrea Duane 1, Jaume Balagué 1, Antoni Curcó 4, Ricard Gutiérrez 5 and Lluís Brotons 1,2,3 1 InForest JRU (CTFC-CREAF), Carretera de Sant Llorenç de Morunys Km 2, 25280 Solsona, Lleida, Spain; [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (A.D.); [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (L.B.) 2 Centre for Ecological Research and Forestry Applications (CREAF), 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès, Spain 3 Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès, Spain 4 Ebro Delta Natural Park, Government of Catalonia, Av. Catalunya, 46, 43580 Deltebre, Spain; [email protected] 5 Ministry of Territory and Sustainability, Government of Catalonia, Dr. Roux, 80, 08017 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-973-481-752 Received: 22 March 2019; Accepted: 13 May 2019; Published: 21 May 2019 Abstract: Making agricultural production compatible with the conservation of biological diversity is a priority in areas in which human–wildlife conflicts arise. The threatened Western Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio) feeds on rice, inducing crop damage and leading to decreases in rice production. Due to the Swamphen protection status, economic compensation policies have been put in place to compensate farmers for these damages, thus requiring an accurate, quantitative, and cost-effective evaluation of rice crop losses over large territories. We used information captured from a UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) equipped with a multispectral Parrot SEQUOIA camera as ground-truth information to calibrate Sentinel-2 imagery to quantify damages in the region of Ebro Delta, western Mediterranean. -

A New Educational Escape-Room-Based Model for the Sustainable Valorization and Management of Cultural and Natural Heritage

NEW EDUCATIONAL ESCAPE-ROOM-BASED MODEL A FOR THE SUSTAINABLE VALORIZATION AND MANAGEMENT OF CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE Emanuele Palla*, Alejandro Gonzalez Lopez, David Gil Aviles, Maria Angeles Sanchez Martinez 1 IES, Marketing y Turismo Alcalà de Henares, Madrid, España Keywords: Spanish civil war, history, memory, conservation, natural environment. 1. Introduction Since 1950, tourism throughout the world has changed considerably thanks to im- provements in transport, conservation, working conditions and the cultural use and enjoyment of historic sites. Previously, it was only the well-off who travelled due to the expense it entailed, but from 1970 to the beginning of 2000, the number of tourists has constantly grown, as travelling has become increasingly more affordable and more popular (Figure 1). As a result of the increase in people travelling for tourism, countries, cities, towns, districts and tourist sites and attractions have adapted themselves to the needs of the local people and visitors [1]. Tourism produces diverse positive effects when people are able to spend a short period of time away from home. It can improve the quality of life of the local people, it generates employment and the circulation of money that induces regional and national governments to create new jobs and professions in other sectors and ultimately con- tributes to economic growth. Nevertheless, as well as the positive effects, there are negative ones to be taken into consideration. In fact, one of the big problems of tourism is that it leads to an increase in pollution, which in turn leads to other negative effects in the field of culture, politics and the natural environment, etc. -

A Review of the Diversity of Aquatic Avifauna in Mizoram, India

Volume 2021 issue 1, pages 6–11 31 March 2021 https://doi.org/10.33493/scivis.21.01.02 REVIEW ARTICLE A review of the diversity of aquatic avifauna in Mizoram, India Christopher John Zomuana Lawlor1,2* and H. Lalthanzara2 1 Department of Zoology, Government Kolasib College, Kolasib 796081, Mizoram 2 Department of Life Sciences, Pachhunga University College, Mizoram University, Aizawl 796001, Mizoram Aquatic avifauna are an important bio-indicator of an ecosystem changes. Received 21 January 2021 Accepted 15 February 2021 Mizoram, one of the north-eastern states of India, lies in one of the richest biodiversity hotspots of the world. Along its water bodies, it is home to several *For correspondence: [email protected] species of resident birds, and is also a temporary home for migrating birds in different seasons. These resident and migratory avifauna form an important Contact us: [email protected] component of most wetland ecosystems, as they are vital components of the food webs. While only the Tamdil and Palak Lake are recognized as wetlands, there are several rivers and smaller water bodies around which aquatic avifauna exist. However, official records comprise of about 14 species of waterbirds belonging to 6 orders and 8 families. Of these, Anatidae, Charadriidae, Scolopacidae, Anhingidae, and Podicipedidae are represented by one species each, while the Ardeidae are represented by four species. Among the 14 species reported so far, two species of the Order Pelicaniformes, namely Anhinga melanogaster (Family Anhingidae) and Ardea insignis (Family Ardeidae) are highly endangered. However, detailed studies are wanting and, while there are sporadic reports of sightings on social media, there is a need for a more comprehensive study of the diversity and seasonal variations of aquatic avifauna around the different water bodies of the state of Mizoram. -

Spain: La Mancha, Coto Donana & Extremadura 2019

Field Guides Tour Report Spain: La Mancha, Coto Donana & Extremadura 2019 May 4, 2019 to May 16, 2019 Chris Benesh & Godfried Schreur For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Early morning encounter with some Greater Flamingos in El Rocio, Donana. Photo by guide Chris Benesh. One of the nice aspects of birding in Europe is the fact that you encounter bird species that are symbols in our common (“western”) folklore, art and culture. European birds have inspired musicians, poets, writers, storytellers, and painters. They have been the models for artists since ancient times, becoming symbols. For example, we all know that the White Stork is supposed to bring good luck and to deliver babies to their parents. The Carrion Crow, with his scary call, brings bad luck and measures distances in direct flight. The Magpie steals silver, gold and jewels. The Cuckoo, from the clock, really says “cuckoo”, and is the unfaithful Cuckoo that cheats. The Robin comes to our window at Christmas time. The Blackbird singing in the dead of night… The Skylark as a messenger between Earth and Heaven. The Turtle Dove symbolizing love, fidelity and trust. The Goldfinch of Fabritius… Of these, the Common Nightingale is special. It is generally known as the musical champion, the best singer in town. It has therefore inspired many musicians, from classic composers like Brahms and Stravinsky, to popular artists like The Everly Brothers (On the wings of a Nightingale), The Eagles, Leonard Cohen, Nora Jones, Judy Collins, etc… Who doesn't know the song “A Nightingale sang in Berkeley Square?" But the common Nightingale has also been used as a symbol of poets or their poetry. -

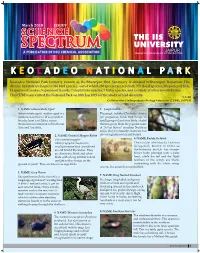

Science Spectrum Issue 9.Cdr

March 2018 ISSUE9 JAIPUR K E O L A D E O N A T I O N A L P A R K Keoladeo National Park formerly known as the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary is situated in Bharatpur, Rajasthan. The diverse habitats are home to 366 bird species, out of which 230 species are resident, 379 floral species, 50 species of fish, 13 species of snakes, 5 species of lizards, 7 amphibian species, 7 turtle species, and a variety of other invertebrates. The CUBE team visited the National Park on 20th Jan 2018 for the study of bird diversity. I- LAB Collaborative Undergraduate Biology Education (CUBE), JAIPUR 1. NAME: Intermediate Egret 5. Jungle Babbler Intermediate egret, median egret is a The jungle babbler (Turdoides striata) medium-sized heron. It is a resident are gregarious birds that forage in breeder from east Africa across small groups of six to ten birds, a habit the Indian subcontinent to South east that has given them the popular name Asia and Australia. of "Seven Sisters" in urban Northern India. They feed mainly on insects, but 2. NAME: Oriental Magpie Robin also eats grains, nectar and berries. 6. NAME: Ruddy Shelduck The oriental magpie- robin (Copsychus saularis) is T h e r u d d y s h e l d u c k ( T a d o r n a small passerine bird considered ferruginea), known in India as an Old World Flycatcher. They the Brahminy duck, It has orange- are distinctive black and white brown body plumage with a paler birds with a long tail that is held head, while the tail and the flight upright as they forage on the feathers in the wings are black, ground or perch. -

Wild Spain Tour (Dani Lopez-Velasco)

These Griffon and Cinereous Vultures at a carcass truly represent our Wild Spain tour (Dani Lopez-Velasco). WILD SPAIN 30 APRIL – 7 MAY 2017 LEADER: DANI LOPEZ-VELASCO 2017 saw yet another highly successful Birdquest tour to Spain, and luckily we were blessed with excellent weather during most of the trip. Great scenery, fantastic food and many exciting birds all on offer, so what else can you ask for in a trip? Our birding began right after leaving Madrid airport, starting with great views of a nesting Eurasian Eagle Owl. Afterwards we headed to Alcazar lagoons in Castilla-La Mancha, where highlights included several smart White-headed Ducks, lots of Greater Flamingos and a vagrant Audouin´s Gull, amongst others. Extremadura lived up to its reputation as being one of the best birding destinations in the world, with excellent views of nesting Black Storks, an overwhelming range of raptors including wonderful views of Spanish Imperial Eagle, as well as Booted, Golden, Short-toed Snake and Bonelli´s Eagles, lots of Cinereous Vultures and Lesser Kestrels and a family of Black-winged Kites. Both Great and Little Bustards showed very well in the steppes too (the very small numbers of Little Bustards that we saw reflected a sudden very steep decline in the whole country), where we also managed to find both Pin-tailed and Black- 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Wild Spain www.birdquest-tours.com bellied Sandgrouse, in flight and on the ground, as well as an obliging Great Spotted Cuckoo. Thekla, Calandra and Greater Short-toed Larks performed to perfection, and warblers were everywhere, with Western Orphean, (Western) Subalpine, Sardinian, Dartford and Western Bonelli´s Warblers all on offer. -

Bearded Vultures in Northwest Europe Christopher Mcinerny and Andy Stoddart, on Behalf of BOURC and BBRC

Bearded Vultures in northwest Europe Christopher McInerny and Andy Stoddart, on behalf of BOURC and BBRC Abstract Over the last 25 years more than 70 Bearded Vultures Gypaetus barbatus have been seen across northwest Europe, many far from their mountain breeding ranges in the Alps and the Pyrenees. It is highly likely that all such extralimital Bearded Vultures originate from reintroduced Alpine populations, which are increasing but not yet considered self-sustaining, rather than from natural populations in the Pyrenees or elsewhere. The species has been placed in Category E (and therefore not part of national bird lists) in all northwest European countries where birds have been seen, apart from Norway where one record is in Category D. This article explains the background to these decisions. World and European range and The Alpine population of Bearded taxonomy Vultures declined substantially during the Bearded Vultures Gypaetus barbatus are nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a result restricted to mountainous regions of the of human persecution, and finally became Palearctic and Africa (del Hoyo et al. 1994; extinct (Mingozzi & Estève 1997; SPB 2018). Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001; BirdLife In the 1980s and 1990s this situation was International 2017). The nominate sub- addressed through coordinated reintroduc- species breeds in southern Europe and north- tion programmes in various Alpine countries west Africa, and from Turkey through the including Austria, France, Italy and Himalayas to northeast China and Mongolia; Switzerland. Birds were first released in 1986 the subspecies meridionalis breeds in the and successful breeding occurred in 1997 western Arabian Peninsula, northeast Africa (Schaub et al. -

Prehistoric Bird Watching in Southern Iberia? the Rock Art of Tajo De Las Figuras Reconsidered

Environmental Archaeology The Journal of Human Palaeoecology ISSN: 1461-4103 (Print) 1749-6314 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yenv20 Prehistoric Bird Watching in Southern Iberia? The Rock Art of Tajo de las Figuras Reconsidered María Lazarich, Antonio Ramos-Gil & Juan Luis González-Pérez To cite this article: María Lazarich, Antonio Ramos-Gil & Juan Luis González-Pérez (2019): Prehistoric Bird Watching in Southern Iberia? The Rock Art of Tajo de las Figuras Reconsidered, Environmental Archaeology, DOI: 10.1080/14614103.2018.1563372 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2018.1563372 Published online: 28 Jan 2019. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yenv20 ENVIRONMENTAL ARCHAEOLOGY https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2018.1563372 Prehistoric Bird Watching in Southern Iberia? The Rock Art of Tajo de las Figuras Reconsidered María Lazarich a, Antonio Ramos-Gil b and Juan Luis González-Pérezb aDepartment of History, Geography and Philosophy, Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, University of Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain; bDepartment of History, Geography and Philosophy, The Prehistory Research Group University of Cádiz (HUM-812), University of Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This paper studies the relationship between humans and birds in the recent prehistory of the Received 30 June 2017 Southern Iberian Peninsula. With its high number of bird, mammal, and anthropomorphic Revised 6 December 2018 paintings, a small rock shelter –Tajo de las Figuras– provides an excellent case study to Accepted 7 December 2018 address this topic. -

British List 2019 02 01

THE BRITISH LIST The official list of bird species recorded in Britain sponsored by Leica Sports Optics This document summarises the Ninth edition of the British List (BOU, 2017. Ibis 160: 190-240) and subsequent changes to the List included in BOURC reports (see p. 13). Category A, B, C species Total no. of species on the British List (Cats A, B, C) = 619 at 1 February 2019 Category A 601 • Category B 8 • Category C 10 Other categories see p.13. The list below includes both the vernacular name used by British birders and the IOC World Bird List international English name (see www.worldbirdnames.org) where these are different to the English vernacular name. British (English) IOC World Bird List Scientific name Category vernacular name international English name Brent Goose Brant Goose Branta bernicla AE Red-breasted Goose † Branta ruficollis AE* Canada Goose ‡ Branta canadensis AC2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis AC2E* Cackling Goose † Branta hutchinsii AE Snow Goose Anser caerulescens AC2E* Greylag Goose Anser anser AC2C4E* Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis AE* Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus AE* Tundra Bean Goose Anser serrirostris AE White-fronted Goose Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons AE* Lesser White-fronted Goose † Anser erythropus AE* Mute Swan Cygnus olor AC2 Bewick’s Swan ‡ Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus AE Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus AE* Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca C1C5E* Shelduck Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna A Ruddy Shelduck † Tadorna ferruginea BDE* Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata C1E* Baikal Teal