Redalyc.SLAVERY and CHILD TRAFFICKING in PUERTO RICO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians(1542) King Charles V

The New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians (1542) King Charles V King Charles V. 1971. The New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians. New York: AMS Press Inc. The Spanish arrival in the Americas arguably posed as many challenges for the Iberian monarchy and its peoples as it did for their New World counterparts. In a very short time span, Spain grew from a loose confederation of kingdoms into a global empire. Even as Christopher Columbus was embarking upon his epic voyage to the West, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella were struggling to consolidate their power over the Iberian peninsula. The more than 700-year effort to repel the Moorish invasion from North Africa had just ended in 1492, and the monarchs faced considerable obstacles. On the one hand, they had to contend with the question of how to assimilate peoples that geography, culture, and religion (the Moors, for instance, were Muslims) long had distanced from one another. On the other hand, and in the absence of a clearly defined common enemy, they had to find a means of maintaining and strengthening their hold over the sizeable population of nobles (hidalgos) who earlier had offered them their loyalty in exchange for the possibilities of material gain. With the fighting over, the monarchs could no longer offer the longstanding incentives of land, honor, and treasure as a means of reigning in the nobility. Ferdinand and Isabella sat atop a veritable powder keg. Columbus's arrival in the New World drew Spain's internal conflicts and challenges into the global arena where distance made them even more problematic. -

California's Legal Heritage

California’s Legal Heritage n the eve of California’s statehood, numerous Spanish Civil Law Tradition Odebates raged among the drafters of its consti- tution. One argument centered upon the proposed o understand the historic roots of the legal tradi- retention of civil law principles inherited from Spain Ttion that California brought with it to statehood and Mexico, which offered community property rights in 1850, we must go back to Visigothic Spain. The not conferred by the common law. Delegates for and Visigoths famously sacked Rome in 410 CE after years against the incorporation of civil law elements into of war, but then became allies of the Romans against California’s common law future used dramatic, fiery the Vandal and Suevian tribes. They were rewarded language to make their cases, with parties on both with the right to establish their kingdom in Roman sides taking opportunities to deride the “barbarous territories of Southern France (Gallia) and Spain (His- principles of the early ages.” Though invoked for dra- pania). By the late fifth century, the Visigoths achieved ma, such statements were surprisingly accurate. The complete independence from Rome, and King Euric civil law tradition in question was one that in fact de- established a code of law for the Visigothic nation. rived from the time when the Visigoths, one of the This was the first codification of Germanic customary so-called “barbarian” tribes, invaded and won Spanish law, but it also incorporated principles of Roman law. territory from a waning Roman Empire. This feat set Euric’s son and successor, Alaric, ordered a separate in motion a trajectory that would take the Spanish law code of law known as the Lex Romana Visigothorum from Europe to all parts of Spanish America, eventu- for the Hispanic Romans living under Visigothic rule. -

Racism in Cuba Ronald Jones

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound International Immersion Program Papers Student Papers 2015 A Revolution Deferred: Racism in Cuba Ronald Jones Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ international_immersion_program_papers Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ronald Jones, "A Revolution Deferred: Racism in Cuba," Law School International Immersion Program Papers, No. 9 (2015). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Immersion Program Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopaA Revolution Deferred sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfRacism in Cuba 4/25/2015 ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj Ron Jones klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe rtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjk Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Slavery in Cuba ....................................................................................................................................... -

Freedom's Mirror Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution by Ada Ferrer

Freedom’s Mirror During the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804,arguablythemostradi- cal revolution of the modern world, slaves and former slaves succeeded in ending slavery and establishing an independent state. Yet on the Spanish island of Cuba, barely fifty miles away, the events in Haiti helped usher in the antithesis of revolutionary emancipation. When Cuban planters and authorities saw the devastation of the neighboring colony, they rushed to fill the void left in the world market for sugar, to buttress the institutions of slavery and colonial rule, and to prevent “another Haiti” from happening in their territory. Freedom’s Mirror follows the reverberations of the Haitian Revolution in Cuba, where the violent entrenchment of slavery occurred at the very moment that the Haitian Revolution provided a powerful and proximate example of slaves destroying slavery. By creatively linking two stories – the story of the Haitian Revolution and that of the rise of Cuban slave society – that are usually told separately, Ada Ferrer sheds fresh light on both of these crucial moments in Caribbean and Atlantic history. Ada Ferrer is Professor of History and Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University. She is the author of Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868–1898,whichwonthe2000 Berk- shire Book Prize for the best first book written by a woman in any field of history. Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 131.111.164.128 on Tue May 03 17:50:21 BST 2016. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139333672 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2016 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 131.111.164.128 on Tue May 03 17:50:21 BST 2016. -

Triangular Trade and the Middle Passage

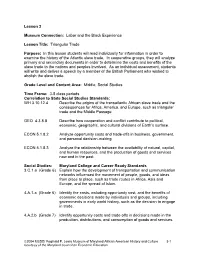

Lesson 3 Museum Connection: Labor and the Black Experience Lesson Title: Triangular Trade Purpose: In this lesson students will read individually for information in order to examine the history of the Atlantic slave trade. In cooperative groups, they will analyze primary and secondary documents in order to determine the costs and benefits of the slave trade to the nations and peoples involved. As an individual assessment, students will write and deliver a speech by a member of the British Parliament who wished to abolish the slave trade. Grade Level and Content Area: Middle, Social Studies Time Frame: 3-5 class periods Correlation to State Social Studies Standards: WH 3.10.12.4 Describe the origins of the transatlantic African slave trade and the consequences for Africa, America, and Europe, such as triangular trade and the Middle Passage. GEO 4.3.8.8 Describe how cooperation and conflict contribute to political, economic, geographic, and cultural divisions of Earth’s surface. ECON 5.1.8.2 Analyze opportunity costs and trade-offs in business, government, and personal decision-making. ECON 5.1.8.3 Analyze the relationship between the availability of natural, capital, and human resources, and the production of goods and services now and in the past. Social Studies: Maryland College and Career Ready Standards 3.C.1.a (Grade 6) Explain how the development of transportation and communication networks influenced the movement of people, goods, and ideas from place to place, such as trade routes in Africa, Asia and Europe, and the spread of Islam. 4.A.1.a (Grade 6) Identify the costs, including opportunity cost, and the benefits of economic decisions made by individuals and groups, including governments in early world history, such as the decision to engage in trade. -

Copyright by Benjamin Nicolas Narvaez 2010

Copyright by Benjamin Nicolas Narvaez 2010 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Nicolas Narvaez Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Chinese Coolies in Cuba and Peru: Race, Labor, and Immigration, 1839-1886 Committee: Jonathan C. Brown, Supervisor Evelyn Hu-DeHart Seth W. Garfield Frank A. Guridy Susan Deans-Smith Madeline Y. Hsu Chinese Coolies in Cuba and Peru: Race, Labor, and Immigration, 1839-1886 by Benjamin Nicolas Narvaez, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2010 Dedication To my parents Leon and Nancy, my brother David, and my sister Cristina. Acknowledgements Throughout the process of doing the research and then writing this dissertation, I benefitted immensely from the support of various individuals and institutions. I could not have completed the project without their help. I am grateful to my dissertation committee. My advisor, Dr. Jonathan Brown, reasonable but at the same time demanding in his expectations, provided me with excellent guidance. In fact, during my entire time as a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, he was a model of the excellence of which a professional historian is capable. Dr. Evelyn Hu-DeHart was kind enough to take an interest in my work and gave me valuable advice. This project would not have been possible without her pioneering research on Asians in Latin America. I also wish to thank the other members of my dissertation committee – Dr. -

Afro-Asian Sociocultural Interactions in Cultural Production by Or About Asian Latin Americans

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 26 September 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201809.0506.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Humanities 2018, 7, 110; doi:10.3390/h7040110 Afro-Asian Sociocultural Interactions in Cultural Production by or About Asian Latin Americans Ignacio López-Calvo University of California, Merced [email protected] Abstract This essay studies Afro-Asian sociocultural interactions in cultural production by or about Asian Latin Americans, with an emphasis on Cuba and Brazil. Among the recurrent characters are the black slave, the china mulata, or the black ally who expresses sympathy or even marries the Asian character. This reflects a common history of bondage shared by black slaves, Chinese coolies, and Japanese indentured workers, as well as a common history of marronage.1 These conflicts and alliances between Asians and blacks contest the official discourse of mestizaje (Spanish-indigenous dichotomies in Mexico and Andean countries, for example, or black and white binaries in Brazil and the Caribbean), which, under the guise of incorporating the Other, favored whiteness, all the while attempting to silence, ignore, or ultimately erase their worldviews and cultures. Keywords: Afro-Asian interactions, Asian Latin American literature and characters, Sanfancón, china mulata, “magical negro,” chinos mambises, Brazil, Cuba, transculturation, discourse of mestizaje Among the recurrent characters in literature by or about Asians in Latin America are the black slave, the china mulata, or the -

CASTLEMAN, BRUCE A. Building the King's Highway. Labor, Society, and Family on Mexico's Caminos Reales 1757–

Book Reviews 149 Castleman, Bruce A. Building the King’s Highway. Labor, Society, and Family on Mexico’s Caminos Reales 1757–1804. University of Arizona Press, Tucson 2005. xii, 163 pp. $39.95; DOI: 10.1017/S0020859007032865 Despite its distinction as the wealthiest and most populated colony of the Spanish empire, Mexico remained poorly developed, suffering from inadequate infrastructure even as late as the end of the colonial period. For decades Mexico’s mercantile elite complained about the poverty of the colony’s system of transportation, especially the lack of an easily navigable road between Mexico City and the principle port of Veracruz. While construction occurred in fits and starts, colonial officials truly embraced the goal of constructing an improved road only in the final decade of the eighteenth century. By the end of Spanish rule, the road was still incomplete. In this interesting study, Bruce Castleman examines the social and economic history of the construction of the Camino Real, the ‘‘King’s Highway’’. The work is largely based on two types of rich archival materials which Castleman skillfully employs. In the first several chapters Castleman analyzes highly suggestive employment records which provide a window into the region’s labor history. A later chapter profits from Castleman’s statistical comparison of censuses taken for the city of Orizaba in the years 1777 and 1793. Along the way, the author makes many interesting arguments. Following an introduction, Chapter 2 presents an overview of the politics surrounding the road’s construction. Building of the highway between Mexico City and Veracruz actually entailed numerous individual localized projects which the viceregal government hoped would eventually connect to one another. -

The Portuguese and Spanish in the Americas

Name: ________________________________________________________________________ Date: _________________________ Class: _____ The Portuguese and Spanish in the Americas Multiple-Choice Quiz – ANSWER KEY Directions: Select the best answer from the given options. 1. Which of the following ships was not part of the 6. Native Americans were forced to work for the fleet of Christopher Columbus in 1492? Spanish under the _____ system. a. Ana Lucia a. encomienda b. Nina b. mercantilism c. Pinta c. patron d. Santa Maria d. socialist 2. What was the capital city of the Aztec? 7. A person of mixed Native American and Spanish a. Chichen Itza descent: b. Guadalajara a. Americano c. Los Angeles b. Indian d. Tenochtitlan c. mestizo d. mulatto 3. Modern Mexico, and a portion of modern Guatemala, were once known as _____. 8. El Camino Real: a. Columbia a. The Real Country b. Los Lobos b. The Real Deal c. New Spain c. The Royal Casino d. Nueva America d. The Royal Road 4. What modern American state, located in the 9. What Aztec ruler was killed in 1520? southeast, was settled by the Spanish in the 16th a. Montezuma century? b. Sitting Bull a. Alabama c. Tupac b. Florida d. Yo Pe c. Georgia d. South Carolina 10. What Spanish explorer traveled into what is now the southwestern United States between 1540 5. A person of mixed African and Spanish descent: and 1542? a. Americano a. Cabrillo b. Indian b. Coronado c. mestizo c. Ponce de Leon d. mulatto d. Verrazzano Visit www.studenthandouts.com for free interactive test-prep games…no log-in required! Name: ________________________________________________________________________ Date: _________________________ Class: _____ 11. -

Ever Faithful

Ever Faithful Ever Faithful Race, Loyalty, and the Ends of Empire in Spanish Cuba David Sartorius Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Tyeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sartorius, David A. Ever faithful : race, loyalty, and the ends of empire in Spanish Cuba / David Sartorius. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5579- 3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5593- 9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Blacks— Race identity— Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba— Race relations— History—19th century. 3. Spain— Colonies—America— Administration—History—19th century. I. Title. F1789.N3S27 2013 305.80097291—dc23 2013025534 contents Preface • vii A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s • xv Introduction A Faithful Account of Colonial Racial Politics • 1 one Belonging to an Empire • 21 Race and Rights two Suspicious Affi nities • 52 Loyal Subjectivity and the Paternalist Public three Th e Will to Freedom • 94 Spanish Allegiances in the Ten Years’ War four Publicizing Loyalty • 128 Race and the Post- Zanjón Public Sphere five “Long Live Spain! Death to Autonomy!” • 158 Liberalism and Slave Emancipation six Th e Price of Integrity • 187 Limited Loyalties in Revolution Conclusion Subject Citizens and the Tragedy of Loyalty • 217 Notes • 227 Bibliography • 271 Index • 305 preface To visit the Palace of the Captain General on Havana’s Plaza de Armas today is to witness the most prominent stone- and mortar monument to the endur- ing history of Spanish colonial rule in Cuba. -

Spanish Colonies

EARLY ENCOUNTERS, 1492-1734 Spanish Colonies Content Warning: This resource addresses sexual assault and physical violence. Resource: Life in Encomienda Background The spread of Catholicism was the stated goal of the Spanish conquest of the New World, but the Spanish also wanted to profit from their new territories. Once the treasure of Native civilizations was looted, colonists turned to mining and plantation farming, and needed to find cheap labor to maximize their profits. In her early instructions for the governance of the colonies, Queen Isabella I of Spain required all Native people to pay tribute to the crown or its representatives. Out of this directive, the encomienda system was born. In this system, encomenderos were awarded the control of all of the Native people who lived in a defined territory, usually in recognition of special services to the crown. For example, conquistador Hernán Cortés was awarded an encomienda territory that included 115,000 Native inhabitants. Cortés’s power over his people was absolute. He could demand tribute in the form of crops or currency. He could force them to construct forts and towns, or work the mines or plantations. He could sexually exploit the women, and even sell the people who worked for him to other encomenderos. In time, the horrors of life on the encomiendas would spark outrage back in Spain. About the Image Bartholomé de las Casas arrived in the New World in 1502 as part of one of the first waves of the Spanish invasion of the Americas. He was rewarded with an encomienda for his services to the crown. -

Sites of Memory of Atlantic Slavery in European Towns with an Excursus on the Caribbean Ulrike Schmieder1

Cuadernos Inter.c.a.mbio sobre Centroamérica y el Caribe Vol. 15, No. 1, abril-setiembre, 2018, ISSN: 1659-0139 Sites of Memory of Atlantic Slavery in European Towns with an Excursus on the Caribbean Ulrike Schmieder1 Abstract Recepción: 7 de agosto de 2017/ Aceptación: 4 de diciembre de 2017 For a long time, the impact of Atlantic slavery on European societies was discussed in academic circles, but it was no part of national, regional and local histories. In the last three decades this has changed, at different rhythms in the former metropolises. The 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in France (1998) and the 200th anniversary of the prohibition of the slave trade in Great Britain (2007) opened the debates to the broader public. Museums and memorials were established, but they coexist with monu- ments to slave traders as benefactors of their town. In Spain and Portugal the process to include the remembrance of slavery in local and national history is developing more slowly, as the impact of slave trade on Spanish and Portuguese urbanization and in- dustrialization is little known, and the legacies of recent fascist dictatorships are not yet overcome. This article focuses on sites of commemoration and silent traces of slavery. Keywords Memory; slave trade; slavery; European port towns; Caribbean Resumen Durante mucho tiempo, la influencia de la esclavitud atlántica sobre sociedades euro- peas fue debatida en círculos académicos, pero no fue parte de historias nacionales, regionales y locales. En las últimas tres décadas esto ha cambiado a diferentes ritmos en las antiguas metrópolis. El 150 aniversario de la abolición de la esclavitud en Francia (1998) y el bicentenario de la prohibición del tráfico de esclavizados en Gran Bretaña (2007) abrieron los debates a un público más amplio.