Paula T. Kelso, “Behind the Curtain: the Body, Control, and Ballet”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov

Spring 2010 Ballet Revi ew From the Spring 2010 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland and Misha Chernov On the cover: New York City Ballet’s Tiler Peck in Peter Martins’ The Sleeping Beauty. 4 New York – Alice Helpern 7 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 8 Lisbon – Peter Sparling 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 11 New York – Sandra Genter 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 New York – Sandra Genter 17 Toronto – Gary Smith 19 New York – Marian Horosko 20 San Francisco – Paul Parish David Vaughan 45 23 Paris 1909-2009 Sandra Genter 29 Pina Bausch (1940-2009) Laura Jacobs & Joel Lobenthal 31 A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov Marnie Thomas Wood Edited by 37 Celebrating the Graham Anti-heroine Francis Mason Morris Rossabi Ballet Review 38.1 51 41 Ulaanbaatar Ballet Spring 2010 Darrell Wilkins Associate Editor and Designer: 45 A Mary Wigman Evening Marvin Hoshino Daniel Jacobson Associate Editor: 51 La Danse Don Daniels Associate Editor: Michael Langlois Joel Lobenthal 56 ABT 101 Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan 61 Osipova’s Season Photographers: 37 Tom Brazil Davie Lerner Costas 71 A Conversation with Howard Barr Subscriptions: Don Daniels Roberta Hellman 75 No Apologies: Peck &Mearns at NYCB Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Annie-B Parson 79 First Class Teachers Associates: Peter Anastos 88 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Robert Gres kovic 93 Alfredo Corvino – Elizabeth Zimmer George Jackson 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 23 Paul Parish 100 Check It Out Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, New York City Ballet: Tiler Peck Sarah C. -

The Reinvention of Baryshnikov 96

Daily Telegraph Aug 10 1996 He was the greatest dancer in the world. Now at 48 he is preparing to return to the London stage. Ismene Brown met him in New York The reinvention of Baryshnikov Photo Ferdinando Scianna/Magnum "Just to watch the Kirov company was like going to church, having a holy experience... when life was miserable the magic of dance was overwhelming" THERE wasn’t a pair of white ballet tights discarded in the gutter as we passed but there might as well have been - all the other symbols were in place. Coming into New York, there were skyscrapers ahead, and to my right a gigantic municipal cemetery, acre upon acre of tombstones. Even the building in which Mikhail Baryshnikov has his office is the Time-Life tower. The passage of time is always cruel to dancers, but never crueller than to the skyscrapers. All dancers know that their career is fugitive, but those who soar above the others have further to fall, and moreover they are flattered into believing that they have a special invincibility not accorded to lesser performers. Who dares tell them when time is up? Or is there another way? Up on the sixth floor, in a hushed, pale place more art gallery than office, a slight, lined man with blue headlights for eyes and a flat, warning voice walked into the room to meet me. “He was the greatest male dancer on the planet. His talent was beyond superlatives. He vaulted into the air with no apparent preparation; he was literally a motion picture. -

September 4, 2014 Kansas City Ballet New Artistic Staff and Company

Devon Carney, Artistic Director FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ellen McDonald 816.444.0052 [email protected] For Tickets: 816.931.2232 or www.kcballet.org Kansas City Ballet Announces New Artistic Staff and Company Members Grace Holmes Appointed New School Director, Kristi Capps Joins KCB as New Ballet Master, and Anthony Krutzkamp is New Manager for KCB II Eleven Additions to Company, Four to KCB II and Creation of New Trainee Program with five members Company Now Stands at 29 Members KANSAS CITY, MO (Sept. 4, 2014) — Kansas City Ballet Artistic Director Devon Carney today announced the appointment of three new members of the artistic staff: Grace Holmes as the new Director of Kansas City Ballet School, Kristi Capps as the new Ballet Master and Anthony Krutzkamp as newly created position of Manager of KCB II. Carney also announced eleven new members of the Company, increasing the Company from 28 to 29 members for the 2014-2015 season. He also announced the appointment of four new KCB II dancers, which stands at six members. Carney also announced the creation of a Trainee Program with five students, two selected from Kansas City Ballet School. High resolution photos can be downloaded here. Carney stated, “With the support of the community, we were able to develop and grow the Company as well as expand the scope of our training programs. We are pleased to welcome these exceptional dancers to Kansas City Ballet and Kansas City. I know our audiences will enjoy the talent and diversity that these artists will add to our existing roster of highly professional world class performers that grace our stage throughout the season ahead. -

Robert J.Mcleod Photography Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8xp7bdz No online items Robert J.McLeod Photography Collection 002.087 Finding aid prepared by Katlin Cunningham and Supriya Wronkiewicz Processing, cataloging, digitization, and access supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. Art Works. Museum of Performance and Design, Performing Arts Library San Francisco, CA 2018 May 31 Robert J.McLeod Photography 002.087 1 Collection 002.087 Title: Robert J.McLeod Photography Collection, Identifier/Call Number: 002.087 Contributing Institution: Museum of Performance and Design, Performing Arts Library Language of Material: English Physical Description: 7.0 Linear feet 7 records cartons Date (inclusive): 1980-2002 Abstract: The Robert J. McLeod Photography Collection is comprised of McLeod's photography in various formats such as printed photographs, film negatives, and 35mm slides, most of which were taken during the 1970’s-1980’s. McLeod worked for the San Francisco Examiner and the San Francisco Chronicle as a photographer and a photo editor for almost forty years, photographing several significant figures and events in the Bay Area. McLeod had a passion for photographing dancers taking classes, in rehearsals and during performances. The collection focuses primarily on ballet dancers and companies from the Bay Area including San Francisco Ballet. The collection also features work by his wife, Beth Witrogen and includes images from other photographers. The collection is arranged in the following series: San Francisco Ballet; Dancers and Choreographers; Individuals; Photographic Materials; and Print Materials. Creator: McLeod, Robert Copyright Copyright has been assigned to the Museum of Performance + Design. Restrictions Entire collection is open for research use. -

Dance 03.12-13.11.Pdf

Artistic Staff Producer Shellie Cash Showcase Co-directors Shellie Cash and Deirdre Carberry Chair & Stage Management Advisor Michele Kay Resident Technical Director Stirling Shelton DANCE Resident Lighting Designer Jim Gage SERIES PRESENTS Sound Advisor Chuck Hatcher Lighting Advisor Mark C. Williams Faculty, Dance Division Shellie Cash (Division Head), Michael Tevlin, Jiang Qi and Deirdre Carberry Adjunct Faculty Suzette Boyer-Webb, Ka-Ron Brown Lehman, Donna Grisez-Weber and Judith Mikita Program Coordinator Colleen Condit CHOREOGRAPHERS’ Staff Assistant Alexis Williams Sierra Crum SHOWCASE Accompanists Chris Barrick, Wen-Mi Chen, Greg Chesney, Robert Conda, Hitomi Koyoma, Mike Lunoe and David Ralphs YOUTH ON THE MOVE Production Staff Shellie Cash & Deirdre Carberry Lighting Designers Mark C. Williams, Tim Schmall, John Cahill and Nik Robalino co-directors Assistant Lighting Designer Celine Graae Resident Master Electrician Ted Rhyner Master Electrician Nik Robalino Assistant Technical Director Stefan Haase Assistant to the Technical Director Olivia Hill Production Assistant Margot Whitney Saturday, March 12, 2:30 and 8:00 p.m. Stage Manager Adam Moser Sunday, March 13, 2:30 p.m. Assistant Stage Manager Ally O’Connell Patricia Corbett Theater Sound Board Operator Kevin Walker Sound Graduate Assistants Hunter Spoede and Doug Wilken Production Crew Gabriel Firestone, Hannah Holthaus, Danny Jama, Alan Kleesattel, Sam Llewellyn, Evelyn Sisler and Welsey Yount Artists’ Profiles, continued Deirdre Carberry, Assistant Professor at CCM Deirdre Carberry joined the faculty at CCM in the fall of 2008. At age 14, Ms. Carberry was invited by Mikhail Baryshnikov PROGRAM to join the American Ballet Theatre. She was the youngest company member to have performed solo and in principal December 9, 1997 roles. -

The Physician at the Movies Peter E

The physician at the movies Peter E. Dans, MD Geoffrey Rush, Colin Firth (as Prince Albert/King George VI), and Helena Bonham Carter in The King’s Speech (2010). The Weinstein Company,/Photofest. The King’s Speech helphimrelaxhisvocalcordsandtogivehimconfidencein Starring Colin Firth, Geoffrey Rush, Helena Bonham Carter, anxiousmoments.Heisalsotoldtoputpebblesinhismouth Guy Pearce, and Derek Jacobi. like Demosthenes was said to have done to speak over the Directed by Tom Hooper. Rated R and PG. Running time 118 waves.Allthatdoesismakehimalmostchoketodeath. minutes. His concerned wife, Elizabeth (Helena Bonham Carter), poses as a Mrs. Johnson to enlist the aid of an unorthodox box-officefavoritewithanupliftingcoherentstorywins speechtherapist,LionelLogue,playedwithgustobyGeoffrey the Academy Award as Best Picture. Stop the presses! Rush. Firth deserved his Academy Award for his excellent AThefilm chronicles the transformation of the Duke of York job in reproducing the disability and capturing the Duke’s (ColinFirth),wholookslike“adeerintheheadlights”ashe diffidence while maintaining his awareness of being a royal. stammers and stutters before a large crowd at Wembley Still,itisRushwhomakesthemoviecomealiveandhasthe StadiumattheclosingoftheEmpireExhibitionin1925, best lines, some from Shakespeare—he apologizes to Mrs. J tohisdeliveryofaspeechthatralliesanationatwar fortheshabbinessofhisstudiowithalinefromOthellothat in1939.Thedoctorswhoattendtowhattheycall being“poorandcontentisrich,andrichenough.”Refusingto tongue-tiednessadvocatecigarettesmokingto -

The Music Center's Study Guide to the Performing Arts

DANCE TRADITIONAL ARTISTIC PERCEPTION (AP) ® CLASSICAL CREATIVE EXPRESSION (CE) Artsource CONTEMPORARY HISTORICAL & CULTURAL CONTEXT (H/C) The Music Center’s Study Guide to the Performing Arts EXPERIMENTAL AESTHETIC VALUING (AV) MULTI-MEDIA CONNECT, RELATE & APPLY (CRA) ENDURING FREEDOM & THE POWER THE HUMAN TRANSFORMATION VALUES OPPRESSION OF NATURE FAMILY Title of Work: Theatre became America’s National Ballet Company®. The Sleeping Beauty About The Artwork: Creators: The story of The Sleeping Beauty was written by Marius Company: American Ballet Theatre (ABT) Choreography: Kevin McKenzie, Gelsey Kirkland and Petipa and Ivan Vsevolojsky, based on a tale by Charles Michael Chernov, after the Perrault. Both the time and the place of this ballet are choreography of Marius Petipa (1889) relatively unimportant because the story is focused on a Music: Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky struggle between good and evil, as represented by the Original Version World Premiere: Imperial Ballet, benevolent Lilac Fairy and the wicked fairy Carabosse. In the Maryinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, 1890 overture, musical themes of both the good and evil fairies are Background Information: introduced. At the christening of the baby Princess Aurora, Recognized as a living national treasure, ABT was founded 5 good faries each give her a loving wish, but the fairy in 1940. The aim was to develop a repertoire of the best Carabosse, feeling left out, casts an evil wish out of revenge. ballets from the past and to encourage the creation of new She states that the princess will prick her finger when she is works by gifted young choreographers. Under the direction 16 and die. Carabosse’s music is low in pitch, strident and of Lucia Chase and Oliver Smith from 1940 to 1980, the aggressive. -

93 Not So Much a Hero, Just a Man Dancing

SUNDAY TELEGRAPH May 30 1993 Not so much a hero, just a man dancing Photo: Justin Leighton On the eve of his London visit, Mikhail Baryshnikov grants Ismene Brown a rare interview THE LAST time I saw Mikhail Baryshnikov he was in his pyjamas. Pink satin ones. I have to admit that it was in public, performing at Sadler's Wells last year. Yet it seemed incongruous: I hadn't had him down as a pink satin pyjama man. Or a pyjama man at all, really. I lobbed this little pleasantry into our conversation when we met last week, and it dropped like a stone in a drought. Eventually Baryshnikov admitted that the day before he had had an encounter with a journalist whose sole interest was his private life. "They want to photograph me in bed, and talk about tumult with women, not about dance. I couldn't believe it," he said furiously. Well, I'm afraid I could. Baryshnikov's fame as a dancer is almost matched by his past visibility as a ladies' man. It seems to me and many other ballet-lovers that his natural sexual charisma is inextricable from the glory of his dancing. But there you are. He undoubtedly has good reason to play down the wild oats now that he has become a family man, with the dancer Lisa Rinehart - along with Peter, almost four, Anna, one, a big house on the Hudson and a family Jeep in which to visit elder daughter Alexandra, 12, and her mother Jessica Lange. It's not only Baryshnikov's lifestyle that seems to have cooled down. -

Dorathi Bock Pierre Dance Collection, 1929-1996

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pc33q9 No online items Finding Aid for the Dorathi Bock Pierre dance collection, 1929-1996 Processed by Megan Hahn Fraser and Jesse Erickson, March 2012, with assistance from Lindsay Chaney, May 2013; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ ©2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Dorathi Bock 1937 1 Pierre dance collection, 1929-1996 Descriptive Summary Title: Dorathi Bock Pierre dance collection Date (inclusive): 1929-1996 Collection number: 1937 Creator: Pierre, Dorathi Bock. Extent: 27 linear ft.(67 boxes) Abstract: Collection of photographs, performance programs, publicity information, and clippings related to dance, gathered by Dorathi Bock Pierre, a dance writer and publicist. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Language of the Material: Materials are in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Methodologies Cultural Studies <=> Critical

Cultural Studies <=> Critical Methodologies http://csc.sagepub.com Globalization, Habitus, and the Balletic Body Steven P. Wainwright, Clare Williams and Bryan S. Turner Cultural Studies <=> Critical Methodologies 2007; 7; 308 DOI: 10.1177/1532708606295652 The online version of this article can be found at: http://csc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/7/3/308 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Studies <=> Critical Methodologies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://csc.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://csc.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://csc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/7/3/308 Downloaded from http://csc.sagepub.com by Christian Hdez on August 10, 2009 Globalization, Habitus, and the Balletic Body Steven P. Wainwright Clare Williams King’s College London Bryan S. Turner National University of Singapore The aim in this article is to write an evocative ethnography of the embodi- ment of ballet as a cultural practice. The authors draw on their fieldwork at the Royal Ballet (London), where they conducted 20 in-depth interviews with ballet staff (and watched “the company at work” in class, rehearsal, and performance). They explored dancers’ (n = 9) and ex-dancers’ (who are now teachers, administrators, and character dancers; n = 11) percep- tions of their bodies, dancing careers, and the major changes that have occurred in the world of ballet over their professional lives. They focus on their accounts of the homogenizing effects of globalization on the culture of the Royal Ballet. Although this research is set within the elite and narrow cul- tural field of dance, the authors hope that it is an interesting addition to broader debates on the interrelationships between individuals and institu- tions, the body and society, and globalization and culture. -

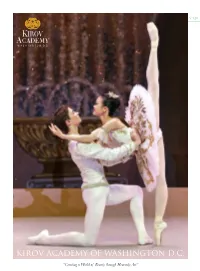

Kirov Academy of Washington D.C

V.1.01 W A S H I N G T O N, D. C. KIROV ACADEMY OF WASHINGTON D.C. “Creating a World of Beauty through Heavenly Art” 2 3 [ Our Vision ] CONTENTS The Kirov Academy is dedicated to artistic and academic excellence and to the investment of a moral education in our 2 Table of Contents students. Founded on universal principles of love, respect, 3 Our Vision and service, The Kirov Academy believes in the importance of the arts and culture in creating a world of beauty and 4 Founders effectuating positive change. 5 Advisory Board 6 History of Kirov Academy 8 Ballet Curriculum Our mission is to inspire students to excel by drawing on the exceptional traditions of the past, and by applying their own 12 Music Curriculum unique talents to become the best they can be. 16 Academy Curriculum 18 Student Life 20 Summer Program 22 Admissions 23 Scholarships 24 Awards 26 Alumni 4 5 [ Founders ] CREATING A WORLD OF BEAUTY THROUGH HEAVENLY ART Sergei Dorensky Sergei Dorensky is known as one of the most outstanding pianists and teachers of the former Soviet Union. Sergei Dorensky has been awarded numerous international prizes over the years and eventually went on to develop his career outside the Soviet Union. Sergei Dorensky was also named “People’s Artist of Russia” in 1989 and received the Order for Merit to the Fatherland in 2008. The vision of the Founders of the Academy, the late Rev. Dr. Sun Myung Moon and Dr. Hak Ja Gary Graffman Han Moon, can be understood in the calligraphy. -

Giselle 05.27-05.29.Pdf

DANCE SERIES PRESENTS Special thanks to: Cincinnati Ballet Company CCM’s Musical Theater Division CCM’s Performance Management Division GISELLE CCM’s Prepatory Division CCM’s Theater, Design & Production Division Contemporary Dance Theater Jiang Qi, director Eugene Ballet Company Nancy Fountain Janice Kennedy Production Staged by: Michael Tevlin and Deirdre Mr. & Mrs. Hal Mandly Carberry (Act One), Jiang Qi (Act Two) Renee Micheo Choreography by: Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot, Alexis Williams Marius Petipa (revival) Composed by: Adolphe Adam Tonight’s performance is made possible by the Corbett-McLain Distinguished Chair in Dance. Costumes: Courtesy of Eugene Ballet Company, Eugene, Oregon Scenery: Northern Illinois University and Schell Scenic Studio Friday, May 27, 8:00 p.m. Saturday, May 28, 2:30 and 8:00 p.m. Sunday, May 29, 2:30 p.m. Patricia Corbett Theater Artistic Staff Producer Shellie Cash Director Jiang Qi PROGRAM Chair & Stage Management Advisor Michele Kay Cast of Characters Resident Technical Director Stirling Shelton Resident Lighting Designer Jim Gage ACT I Sound Advisor Chuck Hatcher Giselle, Peasant Girl Courtney Connor * Resident Lighting Advisor Mark C. Williams Carol Tang + Faculty, Dance Division Shellie Cash (Division Head), Kaitlin Frankenfield # Emma McGirr ^ Deirdre Carberry, Jiang Qi and Michael Tevlin Adjunct Faculty Suzette Boyer-Webb, Berthe, Giselle’s Mother Galina Ponomareva Ka-Ron Brown Lehman, Albrecht, Duke of Silesia Anthony Krutzkamp * Donna Grisez-Weber and Judith Mikita Aaron Hanekamp + Will Gasch