News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2020 New York City Center

NEW YORK CITY CENTER OCTOBER 2020 NEW YORK CITY CENTER SUPPORT CITY CENTER AND Page 9 DOUBLE YOUR IMPACT! OCTOBER 2020 3 Program Thanks to City Center Board Co-Chair Richard Witten and 9 City Center Turns the Lights Back On for the his wife and Board member Lisa, every contribution you 2020 Fall for Dance Festival by Reanne Rodrigues make to City Center from now until November 1 will be 30 Upcoming Events matched up to $100,000. Be a part of City Center’s historic moment as we turn the lights back on to bring you the first digitalFall for Dance Festival. Please consider making a donation today to help us expand opportunities for artists and get them back on stage where they belong. $200,000 hangs in the balance—give today to double your impact and ensure that City Center can continue to serve our artists and our beloved community for years to come. Page 9 Page 9 Page 30 donate now: text: become a member: Cover: Ballet Hispánico’s Shelby Colona; photo by Rachel Neville Photography NYCityCenter.org/ FallForDance NYCityCenter.org/ JOIN US ONLINE Donate to 443-21 Membership @NYCITYCENTER Ballet Hispánico performs 18+1 Excerpts; photo by Christopher Duggan Photography #FallForDance @NYCITYCENTER 2 ARLENE SHULER PRESIDENT & CEO NEW YORK STANFORD MAKISHI VP, PROGRAMMING CITY CENTER 2020 Wednesday, October 21, 2020 PROGRAM 1 BALLET HISPÁNICO Eduardo Vilaro, Artistic Director & CEO Ashley Bouder, Tiler Peck, and Brittany Pollack Ballet Hispánico 18+1 Excerpts Calvin Royal III New York Premiere Dormeshia Jamar Roberts Choreography by GUSTAVO RAMÍREZ -

A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov

Spring 2010 Ballet Revi ew From the Spring 2010 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland and Misha Chernov On the cover: New York City Ballet’s Tiler Peck in Peter Martins’ The Sleeping Beauty. 4 New York – Alice Helpern 7 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 8 Lisbon – Peter Sparling 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 11 New York – Sandra Genter 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 New York – Sandra Genter 17 Toronto – Gary Smith 19 New York – Marian Horosko 20 San Francisco – Paul Parish David Vaughan 45 23 Paris 1909-2009 Sandra Genter 29 Pina Bausch (1940-2009) Laura Jacobs & Joel Lobenthal 31 A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov Marnie Thomas Wood Edited by 37 Celebrating the Graham Anti-heroine Francis Mason Morris Rossabi Ballet Review 38.1 51 41 Ulaanbaatar Ballet Spring 2010 Darrell Wilkins Associate Editor and Designer: 45 A Mary Wigman Evening Marvin Hoshino Daniel Jacobson Associate Editor: 51 La Danse Don Daniels Associate Editor: Michael Langlois Joel Lobenthal 56 ABT 101 Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan 61 Osipova’s Season Photographers: 37 Tom Brazil Davie Lerner Costas 71 A Conversation with Howard Barr Subscriptions: Don Daniels Roberta Hellman 75 No Apologies: Peck &Mearns at NYCB Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Annie-B Parson 79 First Class Teachers Associates: Peter Anastos 88 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Robert Gres kovic 93 Alfredo Corvino – Elizabeth Zimmer George Jackson 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 23 Paul Parish 100 Check It Out Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, New York City Ballet: Tiler Peck Sarah C. -

T H E P Ro G

Friday, February 1, 2019 at 8:30 pm m a r Jose Llana g Kimberly Grigsby , Music Director and Piano o Aaron Heick , Reeds r Pete Donovan , Bass P Jon Epcar , Drums e Sean Driscoll , Guitar h Randy Andos , Trombone T Matt Owens , Trumpet Entcho Todorov and Hiroko Taguchi , Violin Chris Cardona , Viola Clarice Jensen , Cello Jaygee Macapugay , Jeigh Madjus , Billy Bustamante , Renée Albulario , Vocals John Clancy , Orchestrator Michael Starobin , Orchestrator Matt Stine, Music Track Editor This evening’s program is approximately 75 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. Lead support provided by PGIM, the global investment management businesses of Prudential Financial, Inc. Endowment support provided by Bank of America This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano The Appel Room Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall American Songbook Additional support for Lincoln Center’s American Songbook is provided by Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Family Foundation, The DuBose and Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund, The Shubert Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Lincoln Center Spotlight, Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center Public support is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature Nespresso is the Official Coffee of Lincoln Center NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center Artist catering provided by Zabar’s and Zabars.com UPCOMING AMERICAN SONGBOOK EVENTS IN THE APPEL ROOM: Saturday, February 2 at 8:30 pm Rachael & Vilray Wednesday, February 13 at 8:30 pm Nancy And Beth Thursday, February 14 at 8:30 pm St. -

The Reinvention of Baryshnikov 96

Daily Telegraph Aug 10 1996 He was the greatest dancer in the world. Now at 48 he is preparing to return to the London stage. Ismene Brown met him in New York The reinvention of Baryshnikov Photo Ferdinando Scianna/Magnum "Just to watch the Kirov company was like going to church, having a holy experience... when life was miserable the magic of dance was overwhelming" THERE wasn’t a pair of white ballet tights discarded in the gutter as we passed but there might as well have been - all the other symbols were in place. Coming into New York, there were skyscrapers ahead, and to my right a gigantic municipal cemetery, acre upon acre of tombstones. Even the building in which Mikhail Baryshnikov has his office is the Time-Life tower. The passage of time is always cruel to dancers, but never crueller than to the skyscrapers. All dancers know that their career is fugitive, but those who soar above the others have further to fall, and moreover they are flattered into believing that they have a special invincibility not accorded to lesser performers. Who dares tell them when time is up? Or is there another way? Up on the sixth floor, in a hushed, pale place more art gallery than office, a slight, lined man with blue headlights for eyes and a flat, warning voice walked into the room to meet me. “He was the greatest male dancer on the planet. His talent was beyond superlatives. He vaulted into the air with no apparent preparation; he was literally a motion picture. -

Bernhardt Hamlet Cast FINAL

IMAGES AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD HERE CAST ANNOUNCED FOR GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE WEST COAST PREMIERE OF “BERNHARDT/HAMLET” FEATURING GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINEE DIANE VENORA AS SARAH BERNHARDT WRITTEN BY THERESA REBECK AND DIRECTED BY SARNA LAPINE ALSO FEATURING NICK BORAINE, ALAN COX, ISAIAH JOHNSON, SHYLA LEFNER, RAYMOND McANALLY, LEVENIX RIDDLE, PAUL DAVID STORY, LUCAS VERBRUGGHE AND GRACE YOO PREVIEWS BEGIN APRIL 7 - OPENING NIGHT IS APRIL 16 LOS ANGELES (February 24, 2020) – Geffen Playhouse today announced the full cast for its West Coast premiere of Bernhardt/Hamlet, written by Theresa Rebeck (Dead Accounts, Seminar) and directed by Sarna Lapine (Sunday in the Park with George). The production features Diane Venora (Bird, Romeo + Juliet) as Sarah Bernhardt. In addition to Venora, the cast features Nick BoraIne (Homeland, Paradise Stop) as Louis, Alan Cox (The Dictator, Young Sherlock Holmes) as Constant Coquelin, Isaiah Johnson (Hamilton, David Makes Man) as Edmond Rostand, Shyla Lefner (Between Two Knees, The Way the Mountain Moved) as Rosamond, Raymond McAnally (Size Matters, Marvelous and the Black Hole) as Raoul, Rosencrantz, and others, Levenix Riddle (The Chi, Carlyle) as Francois, Guildenstern, and others, Paul David Story (The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, Equus) as Maurice, Lucas Verbrugghe (Icebergs, Lazy Eye) as Alphonse Mucha and Grace Yoo (Into The Woods, Root Beer Bandits) as Lysette. It’s 1899, and the legendary Sarah Bernhardt shocks the world by taking on the lead role in Hamlet. While her performance is destined to become one for the ages, Sarah first has to conVince a sea of naysayers that her right to play the part should be based on ability, not gender—a feat as difficult as mastering Shakespeare’s most Verbose tragic hero. -

Finding Aid for Bolender Collection

KANSAS CITY BALLET ARCHIVES BOLENDER COLLECTION Bolender, Todd (1914-2006) Personal Collection, 1924-2006 44 linear feet 32 document boxes 9 oversize boxes (15”x19”x3”) 2 oversize boxes (17”x21”x3”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x4”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x6”) 8 storage boxes 2 storage tubes; 1 trunk lid; 1 garment bag Scope and Contents The Bolender Collection contains personal papers and artifacts of Todd Bolender, dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet director. Bolender spent the final third of his 70-year career in Kansas City, as Artistic Director of the Kansas City Ballet 1981-1995 (Missouri State Ballet 1986- 2000) and Director Emeritus, 1996-2006. Bolender’s records constitute the first processed collection of the Kansas City Ballet Archives. The collection spans Bolender’s lifetime with the bulk of records dating after 1960. The Bolender material consists of the following: Artifacts and memorabilia Artwork Books Choreography Correspondence General files Kansas City Ballet (KCB) / State Ballet of Missouri (SBM) files Music scores Notebooks, calendars, address books Photographs Postcard collection Press clippings and articles Publications – dance journals, art catalogs, publicity materials Programs – dance and theatre Video and audio tapes LK/January 2018 Bolender Collection, KCB Archives (continued) Chronology 1914 Born February 27 in Canton, Ohio, son of Charles and Hazel Humphries Bolender 1931 Studied theatrical dance in New York City 1933 Moved to New York City 1936-44 Performed with American Ballet, founded by -

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 Pm

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 pm Photo:Photo: Benoit © Paul Lemay Kolnik 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PETER MARTINS ARTISTIC ADMINISTRATOR JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH THE DANCERS PRINCIPALS ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING CHASE FINLAY ABI STAFFORD SOLOIST UNITY PHELAN CORPS DE BALLET MARIKA ANDERSON JACQUELINE BOLOGNA HARRISON COLL CHRISTOPHER GRANT SPARTAK HOXHA RACHEL HUTSELL BAILY JONES ALEC KNIGHT OLIVIA MacKINNON MIRIAM MILLER ANDREW SCORDATO PETER WALKER THE MUSICIANS ARTURO DELMONI, VIOLIN ELAINE CHELTON, PIANO ALAN MOVERMAN, PIANO BALLET MASTERS JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH CRAIG HALL LISA JACKSON REBECCA KROHN CHRISTINE REDPATH KATHLEEN TRACEY TOURING STAFF FOR NEW YORK CITY BALLET MOVES COMPANY MANAGER STAGE MANAGER GREGORY RUSSELL NICOLE MITCHELL LIGHTING DESIGNER WARDROBE MISTRESS PENNY JACOBUS MARLENE OLSON HAMM WARDROBE MASTER MASTER CARPENTER JOHN RADWICK NORMAN KIRTLAND III 3 Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop Photo © Paul Kolnik for all of your instrument, EVENT SPONSORS accessory, and service needs! RICHARD AND MARY JO STANLEY ELLIE AND PETER DENSEN ALLYN L. MARK IOWA HOUSE HOTEL SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Photo: Miriam Alarcón Avila Season Sponsor! Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop for all of your instrument, accessory, and service needs! westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! THE PROGRAM IN THE NIGHT Music by FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Choreography by JEROME ROBBINS Costumes by ANTHONY DOWELL Lighting by JENNIFER TIPTON OLIVIA MacKINNON UNITY PHELAN ABI STAFFORD AND AND AND ALEC KNIGHT CHASE FINLAY ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING Piano: ELAINE CHELTON This production was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. -

Atheneum Nantucket Dance Festival

NANTUCKET ATHENEUM DANCE FESTIVAL 2011 Featuring stars of New York City Ballet & Paris Opera Ballet Benjamin Millepied Artistic Director Dorothée Gilbert Teresa Reichlen Amar Ramasar Sterling Hyltin Tyler Angle Daniel Ulbricht Maria Kowroski Alessio Carbone Ana Sofia Scheller Sean Suozzi Chase Finlay Georgina Pazcoguin Ashley Laracey Justin Peck Troy Schumacher Musicians Cenovia Cummins Katy Luo Gillian Gallagher Naho Tsutsui Parrini Maria Bella Jeffers Brooke Quiggins Saulnier Cover: Photo of Benjamin Millepied by Paul Kolnik 1 Welcometo the Nantucket Atheneum Dance Festival! For 177 years the Nantucket Atheneum has enriched our island community through top quality library services and programs. This year the library served more than 200,000 adults, teens and children year round with free access to over 1.4 million books, CDs, and DVDs, reference and information services and a wide range of cultural and educational programs. In keeping with its long-standing tradition of educational and cultural programming, the Nantucket Atheneum is very excited to present a multifaceted dance experience on Nantucket for the fourth straight summer. This year’s performances feature the world’s best dancers from New York City Ballet and Paris Opera Ballet under the brilliant artistic direction of Benjamin Millepied. In addition to live music for two of the pieces in the program, this year’s program includes an exciting world premier by Justin Peck of the New York City Ballet. The festival this week has offered a sparkling array of free community events including two dance-related book author/illustrator talks, Frederick Wiseman’s film La Danse, Children’s Workshop, Lecture Demonstration and two youth master dance classes. -

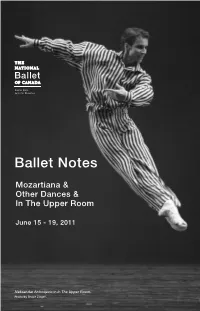

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes, -

Teacher Resource Guide

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School Instructional Performances | March, April 2018 | Teacher Resource Guide Choreography by Jerome Robbins The instructional performances have been made possible by the generosity of the Jerome Robbins Foundation and a donor who wishes to remain anonymous. PBT gratefully acknowledges the following organizations for their commitment to our education programming: Allegheny Regional Asset District Henry C. Frick Educational Fund of The Buhl Anne L. and George H. Clapp Charitable Foundation Trust BNY Mellon Foundation Highmark Foundation Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation Peoples Natural Gas Eat ‘n Park Hospitality Group Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Edith L. Trees Charitable Trust Pennsylvania Department of Community ESB Bank and Economic Development Giant Eagle Foundation PNC Bank Grow up Great The Grable Foundation PPG Industries, Inc. Hefren-Tillotson, Inc. Richard King Mellon Foundation James M. The Heinz Endowments and Lucy K. Schoonmaker 2 CONTENTS 4 The Choreographer—Jerome Robbins Fast Facts 5 The Composer— Leonard Bernstein 6 Robbins’ Style of Movement 7 A look into the instructional performance: Classical Ballet—Swan Lake excerpts Neo-classical Ballet—The Symphony 8 Robbins’ Ballet—West Side Story Suite 9 Exploring West Side Story: Lesson Prompts Connections to Romeo and Juliet Entry Pointes Characters and Story Elements 11 Communication and Technology 12 Group Dynamics 13 Conflict, Strategies and Resolutions 15 Pedestrian Movement and Choreography Observing and Developing Movement 16 Social Dances 17 Creating an Aesthetic 18 Musical Theater/Movie/Ballet PBT celebrates the 100th birthday of Jerome Robbins with its May 2018 production of In the Night, Fancy Free and West Side Story Suite. -

News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 6, NO. 1 (2019) The Jerome Robbins Dance Division: 75 Years of Innovation and Advocacy for Dance by Arlene Yu, Collections Manager, Jerome Robbins Dance Division Scenario for Salvatore Taglioni's Atlanta ed Ippomene in Balli di Salvatore Taglioni, 1814–65. Isadora Duncan, 1915–18. Photo by Arnold Genthe. Black Fiddler: Prejudice and the Negro, aired on ABC-TV on August 7, 1969. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, “backstage.” With this issue, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Jerome Robbins History Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In 1944, an enterprising young librarian at The New York Public Library named One of New York City’s great cultural treasures, it is the largest and Genevieve Oswald was asked to manage a small collection of dance materials most diverse dance archive in the world. It offers the public free access in the Music Division. By 1947, her title had officially changed to Curator and the to dance history through its letters, manuscripts, books, periodicals, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, known simply as the Dance Collection for many prints, photographs, videos, films, oral history recordings, programs and years, has since grown to include tens of thousands of books; tens of thousands clippings. It offers a wide variety of programs and exhibitions through- of reels of moving image materials, original performance documentations, audio, out the year. Additionally, through its Dance Education Coordinator, it and oral histories; hundreds of thousands of loose photographs and negatives; reaches many in public and private schools and the branch libraries. -

5 December 2008 Page 1 of 40

Radio 3 Listings for 29 November – 5 December 2008 Page 1 of 40 SATURDAY 29 NOVEMBER 2008 04:30AM Boulogne, Joseph - Chevalier de Saint-Georges (c.1748-1799) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b00fmc81) Symphony (Op.11 No.1) in G major (Op.11, No.1) 01:01AM Tafelmusik Orchestra, Jeanne Lamon (conductor) Borodin, Alexander (1833-1887) Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor 04:45AM Romanian Radio Academic Chorus, Romanian National Radio Couperin, François (1668-1733) Symphony Orchestra, Alpaslan Ertungealp (conductor) Rondeau – Le Tic-toc-choc (or Les maillotins) from Pieces de clavecin – ordre no.18 01:14AM Colin Tilney (harpsichord) Mendelssohn, Felix (1809-1847) Violin Concerto (Op.64) in E minor, Op.64 04:49AM Cristina Anghelescu (violin), Romanian National Radio Delius, Frederick (1862-1934) arr. Thomas Beecham Symphony Orchestra, Alpaslan Ertungealp (conductor) The Walk to the Paradise Garden BBC Concert Orchestra, Barry Wordsworth (conductor) 01:42AM Ysaÿe, Eugène (1858-1931) 05:00AM Mélancolie Bruch, Max (1838-1920) Cristina Anghelescu (violin) Allegro vivace ma non troppo (Op.83 No.7) in C major arr. for violin, cello & piano 01:45AM Moshe Hammer (violin), Tsuyoshi Tsutsumi (cello), William Tritt Rimsky-Korsakov, Nicolai (1844-1908) (piano) Symphony No 2 (Op.9) Romanian National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Alpaslan 05:04AM Ertungealp (conductor) Goldmark, Károly (1830-1915) Scherzo for orchestra (Op.19) in E minor 02:20AM Hungarian Radio Orchestra, Adam Medveczky (conductor) Shostakovich, Dmitry (1906-1975), arr. Timothy Kain for 4 guitars