The Semantics and Pragmatics of the Japanese Evidentials -Rashii,-Sooda, and -Yooda: an Experimental Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acquaintance Inferences As Evidential Effects

The acquaintance inference as an evidential effect Abstract. Predications containing a special restricted class of predicates, like English tasty, tend to trigger an inference when asserted, to the effect that the speaker has had a spe- cific kind of `direct contact' with the subject of predication. This `acquaintance inference' has typically been treated as a hard-coded default effect, derived from the nature of the predicate together with the commitments incurred by assertion. This paper reevaluates the nature of this inference by examining its behavior in `Standard' Tibetan, a language that grammatically encodes perceptual evidentiality. In Tibetan, the acquaintance inference trig- gers not as a default, but rather when, and only when, marked by a perceptual evidential. The acquaintance inference is thus a grammaticized evidential effect in Tibetan, and so it cannot be a default effect in general cross-linguistically. An account is provided of how the semantics of the predicate and the commitment to perceptual evidentiality derive the in- ference in Tibetan, and it is suggested that the inference ought to be seen as an evidential effect generally, even in evidential-less languages, which invoke evidential notions without grammaticizing them. 1 Introduction: the acquaintance inference A certain restricted class of predicates, like English tasty, exhibit a special sort of behavior when used in predicative assertions. In particular, they require as a robust default that the speaker of the assertion has had direct contact of a specific sort with the subject of predication, as in (1). (1) This food is tasty. ,! The speaker has tasted the food. ,! The speaker liked the food's taste. -

Compositional and Lexical Semantics • Compositional Semantics: The

Compositional and lexical semantics Compositional semantics: the construction • of meaning (generally expressed as logic) based on syntax. This lecture: – Semantics with FS grammars Lexical semantics: the meaning of • individual words. This lecture: – lexical semantic relations and WordNet – one technique for word sense disambiguation 1 Simple compositional semantics in feature structures Semantics is built up along with syntax • Subcategorization `slot' filling instantiates • syntax Formally equivalent to logical • representations (below: predicate calculus with no quantifiers) Alternative FS encodings possible • 2 Objective: obtain the following semantics for they like fish: pron(x) (like v(x; y) fish n(y)) ^ ^ Feature structure encoding: 2 PRED and 3 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 2 PRED 3 7 6 pron 7 6 ARG1 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 ARG1 1 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 4 5 7 6 7 6 7 6 2 3 7 6 PRED and 7 6 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 2 3 7 7 6 6 PRED like v 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 ARG1 6 ARG1 1 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 ARG2 6 6 ARG2 2 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 4 5 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 2 3 7 7 6 6 PRED fish n 7 7 6 6 ARG2 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 ARG 2 7 7 7 6 6 6 1 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 4 5 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 4 5 7 6 7 4 5 3 Noun entry 2 3 2 CAT noun 3 6 HEAD 7 6 7 6 6 AGR 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 4 5 7 6 7 6 COMP 7 6 filled 7 6 7 fish 6 7 6 SPR filled 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 INDEX 1 7 6 2 3 7 6 7 6 SEM 7 6 6 PRED fish n 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 ARG 1 7 7 6 6 1 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 4 5 7 4 5 Corresponds to fish(x) where the INDEX • points to the characteristic variable of the noun (that is x). -

Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected]

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2006 Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Recommended Citation Endresak, David, "Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture" (2006). Senior Honors Theses. 322. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture Degree Type Open Access Senior Honors Thesis Department Women's and Gender Studies First Advisor Dr. Gary Evans Second Advisor Dr. Kate Mehuron Third Advisor Dr. Linda Schott This open access senior honors thesis is available at DigitalCommons@EMU: http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 GIRL POWER: FEMININE MOTIFS IN JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE By David Endresak A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Eastern Michigan University Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in Women's and Gender Studies Approved at Ypsilanti, Michigan, on this date _______________________ Dr. Gary Evans___________________________ Supervising Instructor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Kate Mehuron_________________________ Honors Advisor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Linda Schott__________________________ Dennis Beagan__________________________ Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Heather L. S. Holmes___________________ Honors Director (Print Name and have signed) 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Printed Media.................................................................................................. -

Sentential Negation and Negative Concord

Sentential Negation and Negative Concord Published by LOT phone: +31.30.2536006 Trans 10 fax: +31.30.2536000 3512 JK Utrecht email: [email protected] The Netherlands http://wwwlot.let.uu.nl/ Cover illustration: Kasimir Malevitch: Black Square. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. ISBN 90-76864-68-3 NUR 632 Copyright © 2004 by Hedde Zeijlstra. All rights reserved. Sentential Negation and Negative Concord ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. Mr P.F. van der Heijden ten overstaan van een door het College voor Promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Aula der Universiteit op woensdag 15 december 2004, te 10:00 uur door HEDZER HUGO ZEIJLSTRA geboren te Rotterdam Promotiecommissie: Promotores: Prof. Dr H.J. Bennis Prof. Dr J.A.G. Groenendijk Copromotor: Dr J.B. den Besten Leden: Dr L.C.J. Barbiers (Meertens Instituut, Amsterdam) Dr P.J.E. Dekker Prof. Dr A.C.J. Hulk Prof. Dr A. von Stechow (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen) Prof. Dr F.P. Weerman Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen Voor Petra Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................V 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................1 1.1 FOUR ISSUES IN THE STUDY OF NEGATION.......................................................1 -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

番号 曲名 Name インデックス 作曲者 Composer 編曲者 Arranger作詞

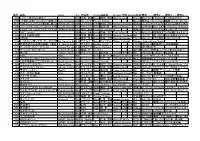

番号 曲名 Name インデックス作曲者 Composer編曲者 Arranger作詞 Words出版社 備考 備考2 備考3 備考4 595 1 2 3 ~恋がはじまる~ 123Koigahajimaru水野 良樹 Yoshiki鄕間 幹男 Mizuno Mikio Gouma ウィンズスコアWSJ-13-020「カルピスウォーター」CMソングいきものがかり 1030 17世紀の古いハンガリー舞曲(クラリネット4重奏)Early Hungarian 17thDances フェレンク・ファルカシュcentury from EarlytheFerenc 17th Hungarian century Farkas Dances from the Musica 取次店:HalBudapest/ミュージカ・ブダペスト Leonard/ハル・レナード編成:E♭Cl./B♭Cl.×2/B.Cl HL50510565 1181 24のプレリュードより第4番、第17番24Preludes Op.28-4,1724Preludesフレデリック・フランソワ・ショパン Op.28-4,17Frédéric福田 洋介 François YousukeChopin Fukuda 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2019年2月スコアは4番と17番分けてあります 840 スリー・ラテン・ダンス(サックス4重奏)3 Latin Dances 3 Latinパトリック・ヒケティック Dances Patric 尾形Hiketick 誠 Makoto Ogata ブレーンECW-0010Sax SATB1.Charanga di Xiomara Reyes 2.Merengue Sempre di Aychem sunal 3.Dansa Lationo di Maria del Real 997 3☆3ダンス ソロトライアングルと吹奏楽のための 3☆3Dance福島 弘和 Hirokazu Fukushima 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2017年6月号サンサンダンス(日本語) スリースリーダンス(英語) トレトレダンス(イタリア語) トゥワトゥワダンス(フランス語) 973 360°(miwa) 360domiwa、NAOKI-Tmiwa、NAOKI-T西條 太貴 Taiki Saijyo ウィンズスコアWSJ-15-012劇場版アニメ「映画ドラえもん のび太の宇宙英雄記(スペースヒーローズ)」主題歌 856 365日の紙飛行機 365NichinoKamihikouki角野 寿和 / 青葉 紘季Toshikazu本澤なおゆき Kadono / HirokiNaoyuki Honzawa Aoba M8 QH1557 歌:AKB48 NHK連続テレビ小説『あさが来た』主題歌 685 3月9日 3Gatu9ka藤巻 亮太 Ryouta原田 大雪 Fujimaki Hiroyuki Harada ウィンズスコアWSL-07-0052005年秋に放送されたフジテレビ系ドラマ「1リットルの涙」の挿入歌レミオロメン歌 1164 6つのカノン風ソナタ オーボエ2重奏Six Canonic Sonatas6 Canonicゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン SonatasGeorg ウィリアム・シュミットPhilipp TELEMANNWilliam Schmidt Western International Music 470 吹奏楽のための第2組曲 1楽章 行進曲Ⅰ.March from Ⅰ.March2nd Suiteグスタフ・ホルスト infrom F for 2ndGustav Military Suite Holst -

The Logic of Argument Structure

32 San Diego Linguistic Papers 3 (2008) 32-125 Circumstances and Perspective: The Logic of Argument Structure Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University 1 Introduction The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Archilochus cited by Isaiah Berlin Berlin (1997:“The Hedgehog and the Fox”) The last couple of decades have seen substantial progress in the study of lexical semantics, particularly in contributing to the understanding of how lexical semantic properties interact with syntactic properties, but many open questions await resolution before a consensus of what a theory of lexical semantics looks like is achieved. Two properties of word meanings contribute to the difficulty of the problem. One is the openness of word meanings. The variety of word meanings is the variety of human experience. Consider defining words such as ricochet, barber, alimony, seminal, amputate, and brittle. One needs to make reference to diverse practices, processes, and objects in the social and physical world: the impingement of one object against another, grooming and hair, marriage and divorce, discourse about concepts and theories, and events of breaking. Before this seemingly endless diversity, semanticists have in the past stopped short, excluding it from the semantic enterprise, and attempting to draw a line between a small linguistically significant set of concepts and the openness of the lexicon. The other problem is the closely related problem of the richness of word meanings. Words are hard to define, not so much because they invoke fine content specific distinctions, but because they invoke vast amounts of background information. The concept of buying presupposes the complex social fact of a commercial event. -

Grounding Lexical Meaning in Core Cognition

Grounding Lexical Meaning in Core Cognition Noah D. Goodman December 2012 (Updated June 2013) Abstract Author's note: This document is a slightly updated and reformatted extract from a grant proposal to the ONR. As a proposal, it aims describe useful directions while reviewing existing and pilot work; it has no pretensions to being a systematic, rigorous, or entirely coherent scholarly work. On the other hand, I've found that it provides a useful overview of a few ideas on the architecture of natural language that haven't yet appeared elsewhere. I provide it for those interested, but with all due caveats. Words are potentially one of the clearest windows on human knowledge and con- ceptual structure. But what do words mean? In this project we aim to construct and explore a formal model of lexical semantics grounded, via pragmatic inference, in core conceptual structures. Flexible human cognition is derived in large part from our ability to imagine possible worlds. A rich set of concepts, in- tuitive theories, and other mental representations support imagining and reasoning about possible worlds|together we call these core cognition. Here we posit that the collection of core concepts also forms the set of primitive elements available for lexi- cal semantics: word meanings are built from pieces of core cognition. We propose to study lexical semantics in the setting of an architecture for language understanding that integrates literal meaning with pragmatic inference. This architecture supports underspecified and uncertain lexical meaning, leading to subtle interactions between meaning, conceptual structure, and context. We will explore several cases of lexical semantics where these interactions are particularly important: indexicals, scalar adjec- tives, generics, and modals. -

Contradiction Detection with Contradiction-Specific Word Embedding

algorithms Article Contradiction Detection with Contradiction-Specific Word Embedding Luyang Li, Bing Qin * and Ting Liu Research Center for Social Computing and Information Retrieval, School of Computer Science and Technology, Harbin Institute of Technology, Haerbin 150001, China; [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (T.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-186-8674-8930 Academic Editor: Toly Chen Received: 18 January 2017; Accepted: 12 May 2017; Published: 24 May 2017 Abstract: Contradiction detection is a task to recognize contradiction relations between a pair of sentences. Despite the effectiveness of traditional context-based word embedding learning algorithms in many natural language processing tasks, such algorithms are not powerful enough for contradiction detection. Contrasting words such as “overfull” and “empty” are mostly mapped into close vectors in such embedding space. To solve this problem, we develop a tailored neural network to learn contradiction-specific word embedding (CWE). The method can separate antonyms in the opposite ends of a spectrum. CWE is learned from a training corpus which is automatically generated from the paraphrase database, and is naturally applied as features to carry out contradiction detection in SemEval 2014 benchmark dataset. Experimental results show that CWE outperforms traditional context-based word embedding in contradiction detection. The proposed model for contradiction detection performs comparably with the top-performing system in accuracy of three-category classification and enhances the accuracy from 75.97% to 82.08% in the contradiction category. Keywords: contradiction detection; word embedding; training data generation; neural network 1. Introduction Contradiction is a kind of semantic relation between sentences. -

Interpreting Focus

INTERPRETING FOCUS BART GEURTS ROB VAN DER SANDT UNIVERSITY OF NIJMEGEN UNIVERSITY OF NIJMEGEN B A R T.G E U R T S@P H I L.R U.N L R V D S A N D T@P H I L.K U N.N L Abstract Although it is widely agreed, if often only tacitly, that there is a close connection between focus and presupposition, recent research has tended to shy away from the null hypothesis, which is that focus is systematically associated with presupposition along the following lines: The Background-Presupposition Rule (BPR) Whenever focusing gives rise to a background λx.ϕ(x), there is a presup- position to the effect that λx.ϕ(x) holds of some individual. This paper aims to show, first, that the evidence in favour of the BPR is in fact rather good, and attempts to clarify its role in the interpretation of focus particles like ‘only’ and ‘too’, arguing that unlike the former the latter is focus-sensitive in an idiosyn- cratic way, adding its own interpretative constraints to those of the BPR. The last part of the paper discusses various objections that have been raised against the BPR, tak- ing a closer look at the peculiarities of ‘nobody’ and ‘somebody’, and comparing the interpretative effects of focusing with those of it-clefts. 26 1 Introduction The phenomenon generally known as focusing raises two questions. First: what is it? Second: how does it affect interpretation? This paper discusses the second question, and proposes a partial answer to it. The first question will not be addressed here. -

Ten Choices for Lexical Semantics

1 Ten Choices for Lexical Semantics Sergei Nirenburg and Victor Raskin1 Computing Research Laboratory New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003 {sergei,raskin}@crl.nmsu.edu Abstract. The modern computational lexical semantics reached a point in its de- velopment when it has become necessary to define the premises and goals of each of its several current trends. This paper proposes ten choices in terms of which these premises and goals can be discussed. It argues that the central questions in- clude the use of lexical rules for generating word senses; the role of syntax, prag- matics, and formal semantics in the specification of lexical meaning; the use of a world model, or ontology, as the organizing principle for lexical-semantic descrip- tions; the use of rules with limited scope; the relation between static and dynamic resources; the commitment to descriptive coverage; the trade-off between general- ization and idiosyncracy; and, finally, the adherence to the “supply-side” (method- oriented) or “demand-side” (task-oriented) ideology of research. The discussion is inspired by, but not limited to, the comparison between the generative lexicon ap- proach and the ontological semantic approach to lexical semantics. It is fair to say that lexical semantics, the study of word meaning and of its representation in the lexicon, experienced a powerful resurgence within the last decade.2 Traditionally, linguistic se- mantics has concerned itself with two areas, word meaning and sentence meaning. After the ascen- dancy of logic in the 1930s and especially after “the Chomskian revolution” of the late 1950s-early 1960s, most semanticists, including those working in the transformational and post-transforma- tional paradigm, focused almost exclusively on sentence meaning. -

Bibliography on Racism

BIBLIOGRAPHY ON RACISM Teun A. van Dijk Version 1.0, May 31, 2007 Aarim-Heriot, N. (2003). Chinese immigrants, African Americans, and racial anxiety in the United States, 1848-82. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. AARP (Organization) , Leadership Conference on Civil Rights., & Library of Congress. (2004). Voices of civil rights. Ordinary people, extraordinary stories.. Washington, D.C.: AARP. Abad Márquez, L. V., Cucó, A., & Izquierdo Escribano, A. (1993). Inmigración, pluralismo y tolerancia. Madrid: Popular. Abanes, R. (1996). American militias. Rebellion, racism & religion. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press. Abanime, E. P. (1986). Ideologies of Race and Sex in Literature: Racism and Antiracism in the African Francophone Novel. College Language Association Journal, 30(2), 125-143. Abbattista, G., & Imbruglia, G. (1992). Il razzismo e le sue storie. Napoli: Edizioni scientifiche italiane. Abbattista, G., Imbruglia, G., Associazione Sigismondo Malatesta., & Convegni malatestiani sul razzismo e le sue storie (1992). Il razzismo e le sue storie. Napoli: Edizioni scientifiche italiane. Abbott, S. (1971). The prevention of racial discrimination in Britain. London New York: published for the United Nations Institute for Training and the Institute of Race Relations by Oxford U.P. Abd Allah, G. (2000). Waqa i al-yawm al-dirasi al-khass bi-al-manahij al-tarbawiyah al-ta limiyah al-Filastiniyah wa-al-Isra iliyah. al-Quds: Markaz al-Dirasat wa-al-Tatbiqat al- Tarbawiyah. Abdel-Shehid, G. (2005). Who da man? Black masculinities and sporting cultures. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press. Abdelaziz, T. (1987). Je, femme d'immigré. Paris: Editions du Cerf. Abdelkhalek, O. (1993). Maghrebins victimes du racisme en France, 1980-1989.