Margaret Edson's Wit and the Art of Analogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clybourne Park Study Guide

Clybourne Park Study Guide The Theatre/Dance Department’s production oF Clybourne Park can be seen December 2 – 7 at 7:30 pm in Barnett Theatre. Tickets 262-472-2222 Monday – Friday 9:30 am – 5:00 pm The Clybourne Park Study Guide was originally created by Studio 180 Theatre, Toronto, Canada, and is being used at UW-Whitewater with Studio 180 Theatre’s permission. www.studio180theatre.com Table of Contents A. Notes for Teachers ...................................................................................................................... 3 B. Introduction to the Company and the Play .................................................................................. 4 UW-Whitewater Theatre/Dance Department .......................................................................................................... 4 Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Bruce Norris – Playwright ................................................................................................................................................. 6 C. Attending the Performance ......................................................................................................... 7 D. Background Information ............................................................................................................. 8 1. Source Material: A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry ....................................................................... -

PLAY GUIDE Inside

McGuire Proscenium Stage / Jan 11 – Feb 16, 2020 Noura by HEATHER RAFFO directed by TAIBI MAGAR PLAY GUIDE Inside THE PLAY Synopsis, Setting and Characters • 4 Responses to Noura • 5 THE PLAYWRIGHT About Heather Raffo •7 In Her Own Words • 8 After the Door Slams: An Interview With Heather Raffo •9 CULTURAL CONTEXT The Long Sweep of History: A Selected Timeline of the Land That Is Now Iraq • 12 What’s What: A Selected Glossary of Terms in Noura • 19 Iraq: Ripped From the Headlines • 22 Chaldean Christians • 24 Meet Cultural Consultant Shaymaa Hasan • 25 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For Further Reading and Understanding • 27 Guthrie Theater Play Guide Copyright 2020 DRAMATURG Carla Steen GRAPHIC DESIGNER Akemi Graves CONTRIBUTORS Shaymaa Hasan, Daisuke Kawachi, Heather Raffo, Carla Steen Guthrie Theater, 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 EDITOR Johanna Buch ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.44.STAGE (toll-free) teachers and individual personal use, no part of this Play Guide may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, artistic director or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Some materials published herein are written especially for our Guide. Others are reprinted by permission of their publishers. The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the imagination, The Guthrie Theater receives support from the National stir the heart, open the mind and build community through the illumination of our Endowment for the Arts. -

In Kindergarten with the Author of WIT

re p resenting the american theatre DRAMATISTS by publishing and licensing the works PLAY SERVICE, INC. of new and established playwrights. atpIssuel 4,aFall 1999 y In Kindergarten with the Author of WIT aggie Edson — the celebrated playwright who is so far Off- Broadway, she’s below the Mason-Dixon line — is performing a Mdaily ritual known as Wiggle Down. " Tapping my toe, just tapping my toe" she sings, to the tune of "Singin' in the Rain," before a crowd of kindergarteners at a downtown elementary school in Atlanta. "What a glorious feeling, I'm — nodding my head!" The kids gleefully tap their toes and nod themselves silly as they sing along. "Give yourselves a standing O!" Ms. Edson cries, when the song ends. Her charges scramble to their feet and clap their hands, sending their arms arcing overhead in a giant "O." This willowy 37-year-old woman with tousled brown hair and a big grin couldn't seem more different from Dr. Vivian Bearing, the brilliant, emotionally remote English professor who is the heroine of her play WIT — which has won such unanimous critical acclaim in its small Off- Broadway production. Vivian is a 50-year-old scholar who has devoted her life to the study of John Donne's "Holy Sonnets." When we meet her, she is dying of very placement of a comma crystallizing mysteries of life and death for ovarian cancer. Bald from chemotherapy, she makes her entrance clad Vivian and her audience. For this feat, one critic demanded that Ms. Edson in a hospital gown, dragging an IV pole. -

POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT in FOUR PLAYS by LYNN NOTTAGE Ludmila MARTANOVSCHI ”Ovidius” University of Constanța This Study Focus

POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT IN FOUR PLAYS BY LYNN NOTTAGE Ludmila MARTANOVSCHI ”Ovidius” University of Constanța Abstract: Since the 1990s, Lynn Nottage’s drama has constantly spoken to audiences and critics alike, as her plays have depicted characters whose individual struggles question the status quo and inspire self- interrogation for audiences in the United States of America and elsewhere. Working with an expanded definition of political engagement, the analysis here examines four plays in which Nottage turns a seamstress from the turn of the twentieth century into a protagonist capable of holding the audience’s attention for the entire length of a play (Intimate Apparel), reevaluates the communist overtones of the fight for racial justice at mid-century (Crumbs from the Table of Joy), exposes lingering colonialism and cultural appropriation (Mud, River, Stone), and attacks extreme violence enacted on women as part of the ravages of war (Ruined). In an interview, Nottage talks about the need to challenge oneself and she does live up to her goal of defying labels. As the current study shows, she cannot simply be celebrated as an African American woman playwright, but as an important voice in American drama today. Keywords: drama, performance, African American identity, race, gender, sisterhood, social change, colonialism in Africa, rewriting history, bearing witness This study focuses on four plays by Lynn Nottage, Crumbs from the Table of Joy (1995), Mud, River, Stone (1998), Intimate Apparel (2003) and Ruined (2008), all of which reflect on essential aspects of political engagement. The analysis first examines the African American women’s experience as revealed by the focus on characters from Manhattan and Brooklyn at two separate historical moments: 1905 in Intimate Apparel and 1950 in Crumbs from the Table of Joy. -

Exploring the Theme of Neo-Orientalism in Ayad Akhtar's

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE, LITERATURE AND TRANSLATION STUDIES (IJELR) A QUARTERLY, INDEXED, REFEREED AND PEER REVIEWED OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.ijelr.in (Impact Factor : 5.9745) (ICI) KY PUBLICATIONS RESEARCH ARTICLE ARTICLE Vol. 7. Issue.1. 2020 (Jan-Mar) EXPLORING THE THEME OF NEO-ORIENTALISM IN AYAD AKHTAR’S DISGRACED AS A REPRESENTATION OF THE ARAB-ISLAMIC WORLD MONA BAGATO E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The goal of this study is to explore Ayad Mkhtar’s “Disgraced”, as a Neo-Orientalist account, portraying the injustice and prejudice of the American society towards Muslims and Arabs, and how it considers them as a threat that must be othered and excluded. The main objective of this study is to reflect on how Disgraced tackled Neo- Orientalist ideology, and consequently how this critical trend has widened the gap between East and West. Intentionally, the West had imposed a Stereotype figure on Article information Received:29/01/2020 Muslims throughout their myopic lens, and consequently created distorted image of Accepted: 27/02/2020 Islam and Muslims in their writings. Since 9/11, the situation has worsened. The Published online: 03/03/2020 classical orientalism has taken a new, and more negative approach. Neo-Orientalists doi: 10.33329/ijelr.7.1.122 now see Muslims as terrorists, lunatics, fundamentalists, and blood-thirsty beings. The stigmata September11th attached to Islam and Muslims drove many second generation immigrates playwrights to do something about it. They could not turn a blind eye to the injustice Muslim Americans are facing in the American society. -

Interactive Ethics Case for February-March 2001

Interactive Ethics Case for February-March 2001 Dear Faculty and Students: The February-March ethics dilemma is based on situations depicted in the Pulitzer Prize- winning play called Wit, written by Margaret Edison. Wit is the story of Dr. Vivian Bearing and her struggle with ovarian cancer. Gritty, funny and unsentimental, the play explores Bearing's journey towards a greater understanding of what it means to live with compassion and die with dignity. This play will be presented from April 11 - May 6 at the Dallas Theater Center. In conjunction with the play, Dallas Theater Center will offer Project Discovery educational programs especially designed for high school groups as well as discounted and free tickets to some performances. For information about these activities, faculty should contact Jennifer King, Director of Education & Community Programs at Dallas Theater Center (214-252-3917 or [email protected]). Because Wit contains nudity, parental and faculty discretion is advised. You are an oncologist (a physician who treats patients with cancer). One of your patients, a 40- year-old woman with a common but usually fatal form of cancer, has agreed to be the first subject in your new experimental treatment program. If your new treatment method causes her type of tumor to regress (get smaller), then you may be able to save many lives. Your patient has advanced cancer at the time treatment begins. Almost immediately the tumor begins to regress. Your patient's overall health deteriorates, however, and you decide to admit her to the hospital. Shortly after arriving at the hospital, she suffers cardiac arrest (her heart stops). -

Undoing Wit: a Critical Exploration of Performance and Medical Education in the Knowledge Economy

Undoing Wit: A Critical Exploration of Performance and Medical Education in the Knowledge Economy by Katherine Margaret Rossiter A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dalla Lana School of Public Health University of Toronto © Copyright by Katherine Margaret Rossiter 2009 Undoing Wit: A Critical Exploration of Performance and Medical Education in the Knowledge Economy Katherine Margaret Rossiter Doctor of Philosophy Dalla Lana School of Public Health University of Toronto 2009 Abstract Over the past decade, there has been a turn in applied health research towards the use of performance as a tool for knowledge translation. The turn to performance in applied health sciences has emerged as researchers have struggled to find new and engaging ways to communicate complex research findings regarding the human condition. However, the turn to performance has occurred within the political landscape of the knowledge economy, and thus conforms to contemporary practices of knowledge production and evaluation. Recent studies about health-based performances exhibit two hallmarks of economized modes of knowledge production. First, these studies focus their attention on the transmission of knowledge to health care professionals through an exposure to performance. Knowledgeable, and thus more useful or efficient, health care providers are the end-product of this transaction. Second, many of these productions are created in the context of application, and thus are driven by an accountability and goals-oriented approach to knowledge acquisition. This thesis argues that economized and rationalized modes of knowledge production do great harm to performance’s pedagogical and ethical potential. By utilizing scientific evaluative methodologies to monitor performance’s ‘success’ as an evaluable, predictable and ends-oriented ii practice obscures performance’s libratory value, and thus misses performance’s potentially most potent and critical contributions. -

Lost in Yonkers (1991 Pulitzer) Neil Simon (1927-) 6 Blithe Spirit (1941) Noel Coward (1899-1973) 7 Peter Pan: the Musical (1904) J

Doctor in the House Seat: Psychoanalysis at the Theatre Jill Savege Scharff, M.D. David E. Scharff, M. D. Copyright © 2012 Jill Savege Scharff and David E. Scharff www.scharffmd.com Cover art Design: Anna Innes Photograph: courtesy of Liz Lerman All Rights Reserved This e-book contains material protected under International and Federal Copyright Laws and Treaties. This e-book is intended for personal use only. Any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is prohibited. No part of this book may be used in any commercial manner without express permission of the author. Scholarly use of quotations must have proper attribution to the published work. This work may not be deconstructed, reverse engineered or reproduced in any other format. The entire e-book in its original form may be shared with other users. Created in the United States of America For information regarding this book, contact the publisher: International Psychotherapy Institute E-Books 6612 Kennedy Drive Chevy Chase, MD 20815-6504 www.freepsychotherapybooks.com [email protected] Dedication For Murray Biggs, Edward Gero and Tappy Wilder Contents 1 The Skin of Our Teeth (1942 Pulitzer) Thornton Wilder (1897-1975) 2 Heartbreak House (1919) George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) 3 Morning’s At Seven (1939) Paul Osborn (1901-1988) 4 The Price (1968) Arthur Miller (1915-2005) 5 Lost in Yonkers (1991 Pulitzer) Neil Simon (1927-) 6 Blithe Spirit (1941) Noel Coward (1899-1973) 7 Peter Pan: The Musical (1904) J. M. Barrie (1860-1937) 8 Theophilus North: The Play (2003) Matthew Burnett (1966 -) 9 Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune (1987) Terrence McNally (1939-) 10 The Goat or Who is Sylvia (2002) Edward Albee (1928-) 11 Proof (2000) David Auburn (1969-) 12 Red (2009) John Logan (1961-) 13 Afterplay (2002) Brian Friel (1929-) Authors Jill Savege Scharff, MD Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University, Supervising Analyst at the International Institute for Psychoanalytic Training, and Teaching Analyst at the Washington Centre for Psychoanalysis, Dr. -

The Reconstruction of the American Identity in Post-9/11 Cinema

An Apocalypse of Change: The Reconstruction of the American Identity in Post-9/11 Cinema Author: Kellen E. O'Gara Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1189 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2010 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. An Apocalypse of Change: The Reconstruction of the American Identity in Post-9/11 Cinema By Kellen O’Gara A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Communication Of Boston College May 2010 1 A man finds his identity by identifying. A man's identity is not best thought of as the way in which he is separated from his fellows, but the way in which he is united with them.” –Robert Terwilliger 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT........................................................................................................................4 CHAPTER ONE- INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………..5 CHAPTER TWO-THE SPARK THAT LIT THE FIRE: THE CRASH THAT SET THE MODERN WORLD AFLAME ………………….....7 CHAPTER THREE-DIVIDED LINES: POST 9/11 RACISM AND INTOLERANCE…………….............................................9 CHAPTER FOUR- AMBIGUITY OF IDENTITY: PREVIOUS STUDIES OF INTOLERANCE, RACISM, AND THE AMERICAN RACIAL IDENTITY…………………………………………………………………...12 CHAPTER FIVE-A HISTORICAL APPROACH TO IDENTITY CONSTRUCTION……………………………………………………………………...22 Progress and Perimeters: Concepts of the Modern Era…………………...…23 Blissful Ambiguity: The Post-Modern Outlook……………………………....25 CHAPTER SIX- -

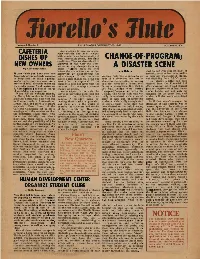

Fiorello's Flute Are Erroneous and Uncalled For

:iiorello' s :nate Volume 2. Nl.nlber 7 F.H. LA GUARDIA COMMUNITY COLLEGE OCTOBER 17, 1974 Automatique is here on a one CAFETERIA year contract and must comply with standards as far as quality of food, reasonable prices, and clean CHANGE·Of·PROGRAM; DISHES UP conditions. They are also subject to approval of the Cafeteria Com NEW OWNERS mittee for any changes including A DISASTER SCENE by Rosemary Serno prices. Reasons must be cited before the committee can act ' on by Gene Cafaro what to do? This student must of If you think you have seen Dew approving or disapproving the necessity carry at least nine credih faces behind the cafeteria counters price change. If the committee Waiting forty-five minutes to an to maintain matriculated status, in Sony and the main building. agrees a price change will occur one hour in a check-out line can be and eligibility for a BEOG grant. you're right. they are new. As a week after the approval. If the almost as disconcerting as waiting In the interim, a letter had been matter of fact, everyone including committee does not agree with the in a rest room for a vacant stall received from the Financial Aid the vendor is new. As of September reasons, Automatique cannot during an emergency. But, that is office warning that if said student 3, Automatique has been in charge change its prices. the way things were during does not register for at least seven of satisfying our appetites. Automatique is actively in Cbange-of-Program at LaGuardia credits helshe will not only be When our old vending friends, volved in providing good food and College. -

Revision, Nostalgia, and Resistance in Contemporary American Drama Sinan Gul University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 Persistence of Memory: Revision, Nostalgia, and Resistance in Contemporary American Drama Sinan Gul University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Gul, Sinan, "Persistence of Memory: Revision, Nostalgia, and Resistance in Contemporary American Drama" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2404. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2404 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Persistence of Memory: Revision, Nostalgia, and Resistance in Contemporary American Drama A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Sinan Gul Ege University Bachelors of Art in English Language and Literature, 2005 Dokuz Eylul University Master of Fine Arts in Stage Arts, 2010 August 2017 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation of the Graduate Council. _________________________ Robert Cochran, PhD Dissertation Director _________________________ _________________________ Dorothy Stephens, PhD Les Wade, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This dissertation focuses on the usages of memory in contemporary American drama. Analyzing selected mainstream and alternative dramatic texts, The Persistence of Memory is a study of personal and communal reflections of the past within contemporary plays. The introduction provides examples from modern plays, major terms, and vital concepts for memory studies and locates their merits in dramatic texts. -

FLORIDA REPERTORY THEATRE GREG LONGENHAGEN, Artistic Director • JOHN MARTIN, Managing Director 2018-2019 SEASON HISTORIC ARCADE THEATRE • FORT MYERS RIVER DISTRICT

FLORIDA REPERTORY THEATRE GREG LONGENHAGEN, Artistic Director • JOHN MARTIN, Managing Director 2018-2019 SEASON HISTORIC ARCADE THEATRE • FORT MYERS RIVER DISTRICT PRESENTS SPONSORED BY WGCU PUBLIC MEDIA MEDIA SPONSOR LEE PITTS LIVE ON FOX 4 STARRING MUJAHID ABDUL-RASHID* • JOHN ARCHIE* • BRIAN D. COATS* MARC ALEXANDER PIERRE* • GAYLE SAMUELS* DANIEL MORGAN SHELLEY* • JOHNIEANN SMITH DIRECTED BY BENNY SATO AMBUSH** SET DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER RICHARD CROWELL DANIELLE PRESTON*** TODD O. WREN*** ensemble member SOUND DESIGNER FIGHT PRODUCTION STAGE ASST. STAGE MANAGER KATIE LOWE CHOREOGRAPHER MANAGER KATELYNN FOSTER KODY C JONES LISA LAMONT* August Wilson’s FENCES is presented by special agreement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. 2018-19 GRAND SEASON SPONSORS IN THE KNOW. IN THE NOW. This entire season sponsored in part by the State of Florida, Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs, and the Florida Council on Arts and Culture. Florida Repertory Theatre is a fully professional non-profit LOA/LORT Theatre company on contract with the Actors’ Equity Association that proudly employs members of the national theatrical labor unions. *Member of Actors’ Equity Association. **Member of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society. ***Member of United Scenic Artists. ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT AUGUST WILSON (April 27, 1945- October 2, 2005) authored Gem of the Ocean, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, The Piano Lesson, Seven Guitars, Fences, Two CAST Trains Running, Jitney, King Hedley II, and Radio (in order of appearance) Golf. These works, called The American Century Troy Maxson................................Mujahid Abdul-Rashid* Cycle, explore the heritage and experience of Jim Bono..................................................................John Archie* African-Americans, decade-by-decade, over the course of the twentieth century.