CSRP Chapter 6-The State's Rail Service and Investment Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

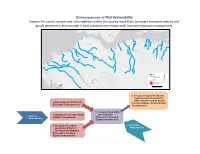

Consequences-Of-Rail

Consequences of Rail Vulnerability Explore the assets, sectors and vulnerabili5es within the county most likely to impact economic ac5vity and goods movement, and consider if local solu5ons can reduce both local and regional consequences. Creeks Infrastructure Marine Oil Terminal Refinery Rail Lines ¸ Burlington Northern Santa Fe Rlwy Union Pacific RR 0 1 2 Miles Copyright: ©2013 Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ 6. Increased congestion impacts transit dependent commuters, GHG emissions and air quality 2. Goods movement affected (Society & Equity + Environmental (Economic Consequences) Consequences) 5. Increased truck traffic 3. Impacts on co-located assets and congestion 1. Railroad (Varied Consequences) (Economic + Society & Vulnerabilities Equity Consequences) 4. Disruption of seaport 7. Interstate operations at Port of Vulnerabilities Richmond and Oakland (Economic + Society & Equity Consequences) 1 Railroad Vulnerabilities Fourteen miles of rail line in the project area is within or passes over the current 100-year floodplain. Seven more miles (or a total of twenty-one miles) may be exposed to a 100-year coastal storm with as little as 6 inches of sea level rise, and a total of forty- one miles may be exposed to a 100-year coastal storm with 30 inches of sea level rise. Lack of information • There is insufficient information available on the UP and BNSF rail lines in the project area to thoroughly evaluate the vulnerability of the rail infrastructure. Governance challenges • Some segments of rail located on the shoreline serve as the first line of defense against flooding, while some are protected by lands owned by others or levees paid for by the public. Not built to withstand flooding • Rail lines are not constructed or maintained to withstand flooding, storm events, wave action or rising groundwater. -

Climate Adaptation Report

Caltrans CCAP: District Interviews Summary October 2019 San Joaquin Council of Governments Climate Adaptation & Resiliency Study Climate Adaptation Report APRIL 2, 2020 1 Climate Adaptation Report March 2020 Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Vulnerability Assessment: Key Findings ...................................................................................................... 10 Gaps and Recommendations ...................................................................................................................... 16 Integrating Transportation Resilience into the Regional Transportation Plan (RTP).............................. 17 Next Steps ................................................................................................................................................... 18 Appendix A: Detailed Vulnerability Assessment Report ............................................................................. 20 Introduction -

Perseverance & Progress Work Program and Budget

2020/2021 Work Program and Budget Perseverance & Progress Built on solid ground, SJRRC will continue through this unprecedented crisis with vision and momentum. ® Table of Contents ® Executive Summary............................3 SJJPA..............................................11 ® Planning.............................................4 Organizational Chart.........................13 Operations.........................................6 Capital Budget.................................14 Stockton Diamond..............................8 ACE Operating Budget.....................15 Capital Projects..................................9 SJJPA Operating Budget .................16 The San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission Board of Directors Christina Fugazi Debby Moorhead Scott Haggerty Chair, City of Stockton Commissioner, City of Manteca Commissioner, Alameda County Leo Zuber Nancy Young John Marchand Vice Chair, City of Ripon Commissioner, City of Tracy Commissioner, City of Livermore Bob Elliott Doug Kuehne Commissioner, San Joaquin County Commissioner, City of Lodi Stacey Mortensen Executive Director 2020/2021 Work Program and Budget 2 Executive Summary The San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission is built on a ing forward and provides much needed jobs for many private solid foundation of political leadership, staff commitment planners, engineers, architects, and construction contractors. and adaptability. The difficult years of the 1998 ACE start- The Valley Rail Program will continue to press forward in the up, the 2003 dot.com implosion, and the 2009 full recession coming year with multiple environmental processes to keep have prepared the agency to deal with the unknowns of the the entire Program on-track and set to deliver transforma- coming year. Staff is prepared to work with less, cover extra tional service expansion for both ACE and the San Joaquins. workload and find ways to leverage and share resources with Also, included in the Capital Program are key passenger other partners. -

West Contra Costa High-Capacity Transit Study

West Contra Costa High-Capacity Transit Study FINAL TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM #4 Summary and Evaluation of Prior Studies September 2015 West Contra Costa High-Capacity Transit Study Document Version Control Revision Updated By Organization Description of Revision Date Incorporate feedback from BART 8/14/2015 Doris Lee Parsons Brinckerhoff Board Member City of Richmond staff requested that South Richmond Transportation 8/20/2015 Doris Lee Parsons Brinckerhoff Connectivity Plan be included. Tech memo updated to note that this plan is covered in Section 2.15 Incorporated edits to address SMG 8/27/2015 Doris Lee Parsons Brinckerhoff and TAC feedback 9/16/15 Tam Tran Parsons Brinckerhoff Made minor edits related to tense Document Sign-off Name Date Signature Rebecca Kohlstrand 09/16/15 ii Draft Summary and Evaluation of Prior Studies September 2015 West Contra Costa High-Capacity Transit Study Table of Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 West Contra Costa County Transportation Setting ........................................... 1 1.2 Study Purpose .................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Purpose of this Technical Memorandum ........................................................... 3 2 Review OF Prior Studies .................................................................................... 4 2.1 BART West Contra Costa Extension Study, 1983 ........................................... -

Contra Costa County Department Of

CONTRA COSTA COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT 651 Pine Street, North Wing - 4th Floor Martinez, CA 94553-1229 Telephone: (925) 335-1201 Fax: (925) 335-1300 TO: Transportation, Water and Infrastructure Committee (Supervisor Gayle B. Uilkema, Chair; Supervisor Mary N. Piepho) FROM: John Greitzer, Transportation Planning Section DATE: September 29, 2008 SUBJECT: Potential reactivation of Mococo freight railroad line RECOMMENDATION: Review this report, discuss with Union Pacific officials at the Committee meeting, and consider providing a report to the full Board or other action as appropriate ATTACHMENTS: • Maps (2) provided by Union Pacific Railroad • Contra Costa Times article, August 18, 2008 • County maps (2) showing street crossings and schools along Union Pacific line The Transportation, Water and Infrastructure Committee has asked staff to provide a report on the potential reactivation of the “Mococo” freight railroad line in eastern Contra Costa County, as reported in recent newspaper articles, and the possible impacts of this action on communities along the route. This report responds to that request. Union Pacific Railroad staff will attend the meeting to discuss the issue with the Committee. Railroad representatives also are meeting with officials in the cities along the Mococo line. Background The Mococo line is the portion of the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) system between Martinez and Tracy in San Joaquin County. The name Mococo is short for Mountain Copper Company, a long- gone smelting operation just east of Martinez that used the railroad line in the early 1900s. From Martinez heading east, the tracks go through the Concord Naval Weapons Station, Bay Point, Pittsburg, Antioch, Oakley, Brentwood, and Byron, and continue southeast along Byron Highway to Tracy. -

Federal Register/Vol. 79, No. 100/Friday, May 23

29840 Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 100 / Friday, May 23, 2014 / Notices Board decisions and notices are UP’s grant of certain operating rights to DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION available on our Web site at PHL over the Subject Track. Surface Transportation Board ‘‘www.stb.dot.gov.’’ PHL states that the agreement Decided: May 19, 2014. between PHL and UP does not contain [Docket No. FD 35827] By the Board, Rachel D. Campbell, any provision that may limit future Director, Office of Proceedings. interchange of traffic with any third- Union Pacific Railroad Company— Raina S. White, party connecting carrier. Temporary Trackage Rights Exemption—Dallas Area Rapid Transit Clearance Clerk. PHL intends to consummate the [FR Doc. 2014–11988 Filed 5–22–14; 8:45 am] and Fort Worth Transportation proposed transaction 30 days or more Authority BILLING CODE 4915–01–P after the exemption was filed (May 7, 2014), or 60 days or more after filing its Trinity Railway Express (TRE),1 certification with the Board pursuant to pursuant to a written trackage rights DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 49 CFR 1150.42(e). agreement dated May 2, 2014, has agreed to grant Union Pacific Railroad Surface Transportation Board PHL certifies that its projected annual Company (UP) temporary overhead revenues as a result of this transaction [Docket No. FD 35814] trackage rights over approximately 1.4 will not result in the creation of a Class miles of the TRE Rail Corridor in Ft. Pacific Harbor Line, Inc.—Operation II or Class I rail carrier. Because PHL’s Worth, Tex., between milepost 610.5 Exemption—Union Pacific Railroad projected annual revenues will exceed (the T&P Station) and milepost 611.9 Company $5 million, PHL certified to the Board (the 6th Street Junction). -

ESCI Report Template Version C

Pinole Fire Department Pinole, California REGIONAL FIRE SERVICE DELIVERY STUDY ADDENDUM March 2020 Regional Fire Service Delivery Study Addendum City of Pinole Fire Department TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................ iii Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... iv SECTION I: EVALUATION OF CURRENT CONDITIONS ...................................................................... 1 Current Conditions ............................................................................................................................ 2 Organizational Overview ............................................................................................................................ 2 Service Area & Infrastructure ...................................................................................................................... 5 Staffing Analysis ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Emergency Management ........................................................................................................................... 7 Fire Prevention ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Training .................................................................................................................................................... -

Railroad Industry Modal Profile an Outline of the Railroad Industry Workforce Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities

Railroad Industry Modal Profile An Outline of the Railroad Industry Workforce Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities October 2011 Version: Release_v3.0 DOT/FRA/ORD-11/20 The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views, positions, or policies of the U.S. Department of Transportation or the Federal Government. Reference to any specific programs does not constitute official Federal Government endorsement or approval of the programs, the views they express, or the services they offer. TABLE of CONTENTS 1. Overview of the Railroad Industry ....................................................................................... 7 2. Current Railroad Workforce ................................................................................................ 9 2.1 Total Estimated Railroad Workforce ............................................................................11 2.1.1 Class I Freight Railroad Companies .....................................................................12 2.1.2 Class I Passenger Railroad: Amtrak ...................................................................13 2.1.3 Regional and Short Line Railroad Companies......................................................14 2.1.4 Manufacturers and Suppliers ...............................................................................14 2.1.5 Union Representation ..........................................................................................14 2.1.6 Major Associations ...............................................................................................14 -

San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority Draft 2019 Business Plan Update Public Review Draft - Track Changes

SAN JOAQUIN JOINT POWERS AUTHORITY DRAFT 2019 BUSINESS PLAN UPDATE PUBLIC REVIEW DRAFT - TRACK CHANGES PREPARED FOR CALIFORNIA STATE TRANSPORTATION AGENCY UPDATED FOR FISCAL YEARS 2019/20 & 2020/2021 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction ..........................................................................................................................12 2. Historical Performance of the Service and Route Characteristics ................................. .15 3 . Existing Trainsets, New Equipment, and Maintenance ................................................... ..24 4. Operating Plan and Strategies .......................................................................................... .27 5 . Short-Term and Longer-Term Capital Improvement Programs ........................................ 35 6 . Performance Standards and Action Plan ........................................................................... 45 7. Establishment of Fares ....................................................................................................... 49 8 . Service Amenities and Food Service ................................................................................ ..51 9. Marketing and Outreach Program ...................................................................................... 53 10 .Annual Funding Requirement .......................................................................................... -

California Rail Fast Facts for 2019 Freight Railroads …

Freight Railroads in California Rail Fast Facts For 2019 Freight railroads ….............................................................................................................................................................27 Freight railroad mileage …..........................................................................................................................................4,971 Freight rail employees …...............................................................................................................................................8,270 Average wages & benefits per employee …...................................................................................................$123,680 Railroad retirement beneficiaries …......................................................................................................................24,500 Railroad retirement benefits paid ….....................................................................................................................$606 million U.S. Economy: According to a Towson University study, in 2017, America's Class I railroads supported: Sustainability: Railroads are the most fuel efficient way to move freight over land. It would have taken approximately 9.3 million additional trucks to handle the 167.4 million tons of freight that moved by rail in California in 2019. Rail Traffic Originated in 2019 Total Tons: 64.0 million Total Carloads: 3,405,000 Commodity Tons (mil) Carloads Intermodal 43.4 3,141,900 Food Products 5.4 56,300 Chemicals -

California Department of Transportation

STAll': OF CALIFORNIA-- - BUSINESS. TRANSPORTATION AND HOUSING AGENCY ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER Governor DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR 1120 N STREET P. 0. BOX 942873 SACRAMENTO, CA 94273-0001 Flex your power! PHONE (916) 654-5266 Be energy efficient! FAX (916) 654-6608 TTY 711 February 18, 2009 The Honorable Alan S. Lowenthal, Chair Senate Transportation Committee P.O. Box 942848 Sacramento, CA 94248-0001 The Honorable Mike Eng, Chair Assembly Transportation Committee P.O. Box 942849 Sacramento, CA 94249-0001 Dear Senator Lowenthal and Assembly Member Eng: Chapter 756, Statutes of 2008 (AB 268, Committee on the Budget) added Section 8879.52 to the Government'Code. The section calls on the California Department of Transportation (Department) to prepare a one-time report regarding certain types of projects funded from the Trade Corridors Improvement Fund program established by Proposition 1B of 2006. Specifically, the legislation requires that: (e) On or before February 18, 2009, the department shall report to the policy committees of each house of the Legislature with jurisdiction over t~ansportation matters, a summary of any memorandum of understanding or any other agreement executed by a railroad company and any state or local transportation agency as it relates to any project fimded with moneys allocated from the TClF. This letter constitutes the report called for by Government Code section 8879.52. BACKGROlJND: In April 2008, the California Transpmtation Commission (Commission) adopted a 79 project, $3.1 billion TCIF program. Of the 79 projects in the initial program, 33 were grade separations, seven were traditional mainline or shortline rail freight projects, ten were on the rail system within the publicly owned Port of Long Beach, two were within the San Diego Metropolitan Transit System owned by San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway's San Ysidro yard, and two were projects on publicly owned intercity or commuter rail rights-of-way "Caltrans impro>·es mobiliTy across California" The Honorable Alan S. -

25 29 Transmittal 1

1 MASTER JOINT REVOCABLE PERMIT NO. 09-18 2 3 4 The City of Los Angeles, a municipal corporation duly organized and existing under its 5 charter and the constitution and laws of the State of California, and the City of Long Beach, a 6 municipal corporation duly organized and existing under its charter and the constitution and laws of 7 the State of California (individually, a "City" and together, the "Cities"), by and through their 8 respective Boards ofHarbor Commissioners, jointly own certain real property located in the County 9 ofLos Angeles. Pursuant to a recommendation adopted by the Board ofHarbor Commissioners of 10 the City of Los Angeles under Resolution No. at its , 20_ meeting, and 11 Resolution No. HD 2656 adopted by the Board of Harbor Commissioners ofthe City ofLong 12 Beach at its March 12, 20R meeting, the Cities hereby issue this Master Joint Revocable Permit 13 (the "Permit") and grant permission to Plains West Coast Terminals LLC, a Delaware limited 14 liability company C'Permittee") to operate and maintain various underground structures such as 15 pipes, pipelines, cables, conduits, casings, and similar structures ("Subsurface Facilities") and 16 facilities such as cathodic protection systems, manholes, communication lines, valves, and meters, 17 that are attached to the Subsurface Facilities ("Appurtenant Facilities"), more particularly described 18 on the Schedule ofPermit Areas attached hereto and made a part hereof as Exhibit A or subsequent 19 Exhibit A(x), within the various permitted areas as defined under Paragraph 1 below (collectively, 20 the "Permit Areas"). This Permit shall be effective upon last execution by the Executive Directors 21 of the respective Harbor Departments of the Cities (the "Executive Directors").