Agricultural Produce Marketing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self Assessment Report (Sar) Department of Management Studies April - 2021

Nandha Engineering College (Autonomous), Affiliated to Anna University, Chennai SELF ASSESSMENT REPORT (SAR) DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES APRIL - 2021 NBCC Place, 4th Floor East Tower, Bhisham Pitamah Marg, Pragati Vihar New Delhi 110003 P: +91(11)24360620-22, 24360654, Fax: +91(11) 24360682 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.nbaind.org SAR Contents Section Item Page No. PART A Institutional Information 1 PART B Criteria Summary 8 1 Vision, Mission & Program Educational Objectives 9 2 Governance, Leadership & Financial Resources 17 3 Program Outcomes & Course Outcomes 72 4 Curriculum & Learning Process 100 5 Student Quality and Performance 149 6 Faculty Attributes and Contributions 176 7 Industry & International Connect 212 8 Infrastructure 234 9 Alumni Performance and Connect 258 10 Continuous Improvement 275 PART C Declaration by the Institution 291 Annexure - I Program Outcomes (POs) 292 Department of Management Studies Nandha Engineering College(Autonomous) PART A: Institutional Information 1. Name and Address of the Institution: Nandha Engineering College (Autonomous), Perundurai Main Road, Vaikkaalmedu, Pitchandampalayam (PO), Erode-638052 TamilNadu. Ph : 04294 – 225585, 226393 Mail: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.nandhaengg.org 2. Name and Address of the Affiliating University, if applicable: Anna University Guindy, Chennai, Tamil Nadu - 600025 Ph: 044 - 22357264, 22357265 3. Year of establishment of the Institution: 2001 4. Type of the Institution: Institute of National Importance University Deemed University Autonomous √ Autonomous Status granted in the year : 2013 Renewal of the Autonomous status : 2018 Affiliated Institution AICTE Approved PGDM Institutions Any other (Please specify) NBA/Self Assessment Report (SAR)/NEC/MBA 1 Department of Management Studies Nandha Engineering College(Autonomous) Provide Details: Note: In case of Autonomous and Deemed University, mention the year of grant of status by the authority 5. -

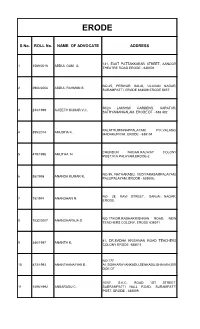

S.No. ROLL No. NAME of ADVOCATE ADDRESS

ERODE S.No. ROLL No. NAME OF ADVOCATE ADDRESS 131, EAST PATTAKKARAR STREET, AANOOR 1 1569/2016 ABDUL GANI A. THEATRE ROAD ERODE - 638001. NO.45, PERIYAR SALAI, ULAVAN NAGAR, 2 2906/2006 ABDUL RAHMAN S. SURAMPATTI, ERODE 638009 ERODE DIST. 50/23 LAKSHMI GARDENS, KARATUR, 3 234/1999 AJIEETH KUMAR V.C. SATHYAMANGALAM. ERODE DT - 638 402 KALATHUMINNAPPALAYAM, P.K.VALASO, 4 395/2014 AMUDHA K. MADAKURICHI, ERODE - 638104 CHENDUR NAGAR,RALWAY COLONY 5 479/1998 AMUTHA N. POST,R.N.PALAYAM,ERODE-2 NO.59, NATHAKADU, VEDIYARASAMPALAYAM, 6 58/1998 ANANDA KUMAR K. PALLIPALAYAM, ERODE - 638008. NO. 28, RAVI STREET, SANJAI NAGAR, 7 75/1974 ANANDHAN N. ERODE. NO:17/4,DR.RADHAKRISHNAN ROAD, NEW 8 1032/2007 ANANDHARAJA S. TEACHERS COLONY, ERODE 638011 41, DR.RADHA KRISHNAN ROAD TEACHERS 9 340/1997 ANANTH K. COLONY ERODE -638011 NO:177 10 873/1993 ANANTHANAYAKI B. A1,SOKKARAYANKADU,SENKADU,BHAVANI,ER DOE DT 10/57, S.K.C. ROAD 1ST STREET, 11 1496/1992 ANBARASU C. SUBRAMPATTI NALL ROAD, SURAMPATTI POST, ERODE - 638009. S.No. ROLL No. NAME OF ADVOCATE ADDRESS 422A, VAKKIL THOTTAM, MANICKAMPALAYAM, 12 2303/2006 ANITHA C. ERODE 638004 ERODE DIST. NO. 37/2, SELVAM NAGAR, 5TH STREET, 13 448/1994 ANNADURAI L. KUMILANKUTTAI, ERODE - 638011. 32/46, THIRUMALAI STREET, VEERAPPAN 14 220/1976 ANNADURAI M. CHATRAM (P.O.), ERODE 638004 2/16, RANA NAGAR, BHAVANI - 638301. ERODE 15 2407/2015 ANU RADHA V. DISTRICT. 82/A, KOVALAN STREET, TEACHERS COLONY, 16 1649/2014 ANUPRIYA M. ERODE - 638 011 NO.34, PANNAI NAGAR, VEERAPPAM 17 224/1988 APPUSAMY S. -

List of Town Panchayats Name in Tamil Nadu Page 1 District Code

List of Town Panchayats Name in Tamil Nadu Sl. No. District Code District Name Town Panchayat Name 1 1 KANCHEEPURAM ACHARAPAKKAM 2 1 KANCHEEPURAM CHITLAPAKKAM 3 1 KANCHEEPURAM EDAKALINADU 4 1 KANCHEEPURAM KARUNGUZHI 5 1 KANCHEEPURAM KUNDRATHUR 6 1 KANCHEEPURAM MADAMBAKKAM 7 1 KANCHEEPURAM MAMALLAPURAM 8 1 KANCHEEPURAM MANGADU 9 1 KANCHEEPURAM MEENAMBAKKAM 10 1 KANCHEEPURAM NANDAMBAKKAM 11 1 KANCHEEPURAM NANDIVARAM - GUDUVANCHERI 12 1 KANCHEEPURAM PALLIKARANAI 13 1 KANCHEEPURAM PEERKANKARANAI 14 1 KANCHEEPURAM PERUNGALATHUR 15 1 KANCHEEPURAM PERUNGUDI 16 1 KANCHEEPURAM SEMBAKKAM 17 1 KANCHEEPURAM SEVILIMEDU 18 1 KANCHEEPURAM SHOLINGANALLUR 19 1 KANCHEEPURAM SRIPERUMBUDUR 20 1 KANCHEEPURAM THIRUNEERMALAI 21 1 KANCHEEPURAM THIRUPORUR 22 1 KANCHEEPURAM TIRUKALUKUNDRAM 23 1 KANCHEEPURAM UTHIRAMERUR 24 1 KANCHEEPURAM WALAJABAD 25 2 TIRUVALLUR ARANI 26 2 TIRUVALLUR CHINNASEKKADU 27 2 TIRUVALLUR GUMMIDIPOONDI 28 2 TIRUVALLUR MINJUR 29 2 TIRUVALLUR NARAVARIKUPPAM 30 2 TIRUVALLUR PALLIPATTU 31 2 TIRUVALLUR PONNERI 32 2 TIRUVALLUR PORUR 33 2 TIRUVALLUR POTHATTURPETTAI 34 2 TIRUVALLUR PUZHAL 35 2 TIRUVALLUR THIRUMAZHISAI 36 2 TIRUVALLUR THIRUNINDRAVUR 37 2 TIRUVALLUR UTHUKKOTTAI Page 1 List of Town Panchayats Name in Tamil Nadu Sl. No. District Code District Name Town Panchayat Name 38 3 CUDDALORE ANNAMALAI NAGAR 39 3 CUDDALORE BHUVANAGIRI 40 3 CUDDALORE GANGAIKONDAN 41 3 CUDDALORE KATTUMANNARKOIL 42 3 CUDDALORE KILLAI 43 3 CUDDALORE KURINJIPADI 44 3 CUDDALORE LALPET 45 3 CUDDALORE MANGALAMPET 46 3 CUDDALORE MELPATTAMPAKKAM 47 3 CUDDALORE PARANGIPETTAI -

May 19, 2012 00:00 IST | Updated: May 19, 2012 05:05 IST

Published: May 19, 2012 00:00 IST | Updated: May 19, 2012 05:05 IST Cotton prices decline on low buying Price of the widely-used Shankar 6 variety of cotton in the country has dropped to Rs. 33,700- Rs. 33,500 a candy because of low demand in the domestic market and declining prices in the international market. A couple of months ago, the Union Government withdrew the suspension on cotton exports and prices started going up expecting export demand. However, the prices are on a downtrend for the last 10 days. Now, the price of Indian cotton is slightly higher than in the international market. China is not likely to be in the market for some time and the demand is low from other countries too because of the economic crisis in some of the European countries, according to K.N. Viswanathan, vice-president of Indian Cotton Federation. The domestic yarn market is also not as good as it was last month and most of the mills are purchasing just one to one-and-a-half month stock. Thus, there is no buying pressure from the domestic mills, he says. Availability of cotton is not a problem now. However, it may become a problem in two or three months when the cotton season comes to an end, says D.K. Nair, secretary general of Confederation of Indian Textile Industry. Published: May 19, 2012 00:00 IST | Updated: May 19, 2012 05:05 IST Sell red gingelly upon harvest Price expected is between Rs. 50 a kg and Rs. -

National Symposium on Spices and Aromatic Crops (Symsac –Viii)

NATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON SPICES AND AROMATIC CROPS (SYMSAC –VIII) Towards 2050 - Strategies for Sustainable Spices Production 16-18 December 2015 Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu SOUVENIR & ABSTRACTS Organized by Tamil Nadu Agricultural University Indian Society for Spices Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu Kozhikode, Kerala In collaboration with Indian Council of Agricultural Research,New Delhi National Horticulture Board,Gurgaon, Haryana ICAR-Indian Institute of Spices Research, Kozhikode, Kerala Directorate of Arecanut& Spices Development, Kozhikode, Kerala National Symposium on Spices and Aromatic Crops (SYMSAC VIII) Towards 2050 - Strategies for Sustainable Spices Production 16-18 December 2015, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu Organized by Indian Society for Spices, Kozhikode, Kerala Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu Compiled and Edited by Krishnamurthy K S, Biju C N, Jayashree E, Prasath D, Dinesh R, Suresh J&NirmalBabu K Cover Design Sudhakaran A Typesetting Deepthi P Citation Krishnamurthy K S, Biju C N, Jayashree E, PrasathD,Dinesh R, Suresh J&NirmalBabu K (Eds) 2015. Souvenir and Abstracts, National Symposium on Spices and Aromatic Crops (SYMSAC VIII): Towards 2050 - Strategies for Sustainable Spices Production, Indian Society for Spices, Kozhikode, Kerala, India Published by Indian Society for Spices, Kozhikode, Kerala December 2015 The financial assistance received from Research and Development Fund of National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) -

Agriculture 2020

AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT POLICY NOTE Demand No. 5 - AGRICULTURE 2020 - 2021 © GOVERNMENT OF TAMILNADU 2020 Policy Note 2020-2021 INDEX S.No. Contents Page No. Introduction 1-13 1. Agriculture 14-180 Horticulture and Plantation 2. 181-261 Crops 3. Agricultural Engineering 262-321 Agricultural Education, Research 4. 322-354 and Extension Education 5. Sugar 355-363 Seed Certification and Organic 6. 364-387 Certification Agricultural Marketing and 7. 388-463 Agri Business Tamil Nadu Watershed 8. Development Agency 464-479 (TAWDEVA) 9. Demand 480-483 Conclusion 484-489 INTRODUCTION “RH‹W«V®¥ ËdJ cyf« mjdhš cHªJ« cHnt jiy” (ÂU¡FwŸ: 1031) Agriculture, though laborious, is the most excellent (form of labour); for people, though they go about (in search of various employments), have at last to resort to the farmer. ***** Tamil Nadu is the 11th largest State in India by area and the 6th most populous State. In Agriculture front, the State Government has set on to usher in Second Green Revolution for doubling the crop production and tripling the farmers’ income and formulated policies and innovative steps to achieve equitable, 1 competitive and sustainable growth in agriculture. To increase their income and to provide “Food Security”, the Government initiated various measures especially in planning to prepare road maps through “Tamil Nadu Vision 2023”, Food Grain Mission, District Agricultural Plan, State Agricultural Plan and Agricultural Infrastructure Development Programme under RKVY and District and State Irrigation Plan under PMKSY etc. Such initiatives helped in drawing implementable action plans, convergence of efforts and focus the constraints in a better tactical and strategic level. -

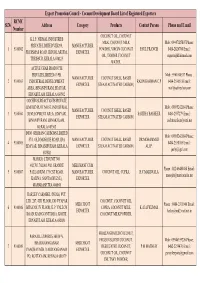

Exporters List

Export Promotion Council - Coconut Development Board List of Registered Exporters RCMC Sl.No Address Category Products Contact Person Phone and E mail Number COCONUT OIL, COCONUT K.L.F. NIRMAL INDUSTRIES MILK, COCONUT MILK Mob : 09447025807 Phone : PRIVATE LIMITED VIII/295, MANUFACTURER 1 9100002 POWDER, VIRGIN COCONUT PAUL FRANCIS 0480-2826704 Email : FR.DISMAS ROAD, IRINJALAKUDA, EXPORTER OIL, TENDER COCONUT [email protected] THRISSUR, KERALA 680125 WATER, ACTIVE CHAR PRODUCTS PRIVATE LIMITED 63/9B, Mob : 9961000337 Phone : MANUFACTURER COCONUT SHELL BASED 2 9100003 INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT RAZIN RAHMAN C.P 0484-2556518 Email : EXPORTER STEAM ACTIVATED CARBON, AREA, BINANIPURAM, EDAYAR, [email protected] ERNAKULAM, KERALA 683502 COCHIN SURFACTANTS PRIVATE LIMITED PLOT NO.63, INDUSTRIAL Mob : 09895242184 Phone : MANUFACTURER COCONUT SHELL BASED 3 9100004 DEVELOPMENT AREA, EDAYAR, SAJITHA BASHEER 0484-2557279 Email : EXPORTER STEAM ACTIVATED CARBON, BINANIPURAM, ERNAKULAM, [email protected] KERALA 683502 INDO GERMAN CARBONS LIMITED Mob : 09895242184 Phone : 57/3, OLD MOSQUE ROAD, IDA MANUFACTURER COCONUT SHELL BASED DR.MOHAMMED 4 9100005 0484-2558105 Email : EDAYAR, BINANIPURAM, KERALA EXPORTER STEAM ACTIVATED CARBON, ALI.P. [email protected] 683502 MARICO LTD UNIT NO. 402,701,702,801,902, GRANDE MERCHANT CUM Phone : 022-66480480 Email : 5 9100007 PALLADIUM, 175 CST ROAD, MANUFACTURER COCONUT OIL, COPRA, H.C MARIWALA [email protected] KALINA, SANTACRUZ (E), EXPORTER MAHARASHTRA 400098 HARLEY CARMBEL (INDIA) PVT. LTD. 287, -

Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission Bulletin

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN-466/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 196/2009 2018 [Price: Rs. 145.60 Paise. TAMIL NADU PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION BULLETIN No. 7] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, MARCH 16, 2018 Panguni 2, Hevilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu-2049 CONTENTS DEPARTMENTAL TESTS—RESULTS, DECEMBER 2017 NAME OF THE TESTS AND CODE NUMBERS Pages Pages The Tamil Nadu Government office Manual Departmental Test for Junior Assistants In Test (Without Books & With Books) the office of the Administrator - General (Test Code No. 172) 552-624 and official Trustee- Second Paper (Without Books) (Test Code No. 062) 705-706 the Account Test for Executive officers (Without Books& With Books) (Test Code No. 152) 625-693 Local Fund Audit Department Test - Commercial Book - Keeping (Without Books) Survey Departmental Test - Field Surveyor’s (Test Code No. 064) 706-712 Test - Paper -Ii (Without Books) (Test Code No. 032) 694-698 Fisheries Departmental Test - Ii Part - C - Fisheries Technology (Without Books) Fisheries Departmental Test - Ii Part - B - (Test Code No. 067) 712 Inland Fisheries (Without Books) (Test Code No. 060) 698 Forest Department Test - forest Law and forest Revenue (Without Books) Fisheries Departmental Test - Ii Part - (Test Code No. 073) 713-716 A - Marine Fisheries (Without Books) (Test Code No. 054) 699 Departmental Test for Audit Superintendents of Highways Department - Third Paper Departmental Test for Audit Superintendents (Constitution of India) (Without Books) of Highways Department - First Paper (Test Code No. 030) 717 (Precis and Draft) (Without Books) (Test Code No. 020) 699 The Account Test for Public Works Department officers and Subordinates - Part - I (Without Departmental Test for the officers of Books & With Books) (Test Code No. -

Customer Name Address Cto Chepauk Asst Circle 10

CUSTOMER NAME ADDRESS CTO CHEPAUK ASST CIRCLE 10 MUKTHARUNISE BEGE M STREET,M ST,IST LANE,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600005 SIVAPRASAD K KARANEESWEAR KOIL ST,,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600005 THE CTO CHEPAUK ASSESSMENT CH 2,,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600002 THE CTO CHEPAUK ASS CIR NAHAVI ,,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600002 CTO TRIPLICANE A C RAINBOW PAI ST,CHENNAI 2,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600001 N RAMADAS STREET,CHENNAI 2,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600001 SHIEK MAGDOOM SAHIB TRIPLICANE,CHENNAI 5,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600005 CTO CHEPAUK DIVN 4 MOULANA MARKET,MADRAS 5,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600001 CTO CHEPAUK ASSESSMENT CIRCLE 18 TRIPLICANE HIGHRD,MADRAS 5,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600005 CTO CHEPAUK ASSESSMENT CIRCLE 305-9 TRIPLICANE HIGH ROAD,H ROAD MADRAS 5,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600005 CTO CHEPAUK ASSESSMENT CIRCLE 305 9 TRIPLICANE HIG,H ROAD,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600005 CTO CHEPAUK ASSESSMENT CIRCLE 63 PV KOIL STREET,MADRAS 14,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600014 CTO CHEPAUK 74 WALLAJAH ROAD,MADRAS 2,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600001 CTO CHEPAUK ASSESSMENT CIRCLE 120 WALLAJAH ROAD,MADRAS 2,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600001 CTO VALLUVARKOTTAM ASSE CIRCLE 24 SARASWATHI STREET,MAHALINGPURAM,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600005 THE DIVI ENGRR HIGHWAYS TUTICO VAITICHETTY PAALAYAN,TURAIYUR TK,TIRUCHIRAPPALLI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,620001 K KUMAR 42 NALLAPPA VATIER,MADRAS 600021,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600021 KHIVRAJ AUTOMOBILES 26 2 AZUEKHAN STREET,MS 5,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600005 KHIVARAJ AUTOMOBILES 27 THAKKADEEN KHAN B,AHADUR ST,CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,INDIA,600005 -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2012 [Price: Rs. 31.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 26] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, JULY 4, 2012 Aani 20, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2043 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 1541-1617 Notice .. 1617 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 22856. My daughter, B. Parameswari, born on 7th May 22859. My daughter, G. Janani, born on 9th June 2001 1996 (native district: Erode), residing at Old No. 316/319, (native district: Tiruvallur), residing at Old No. 4, New No. 92/4, New No. 320, Kunnathur Road, Perundurai, Erode-638 052, Palla Street, Korattur, Chennai-600 076, shall henceforth be shall henceforth be known as K.B. PARAMESHPARI. known as G. JAIWANTHICA. T.G.K. BOOPATHIIE. G. GUNAASEKAR. Perundurai, 25th June 2012. (Father.) Chennai, 25th June 2012. (Father.) 22857. My daughter, B. Tharanikeswari, born on 22860. I, R. Nalini Begum, wife of Thiru Abdul Rahaman, 26th January 1998 (native district: Erode), residing at born on 14th July 1974 (native district: Chennai), residing at Old No. 316/319, New No. 320, Kunnathur Road, Perundurai, No. 1, Vathiyar Chinna Pillai Street, Royapettah, Chennai- Erode-638 052, shall henceforth be known 600 014, shall henceforth be known as R. -

COIMBATORE REGIONAL PLAN – 2038 Volume 2 Erode Sub Region

COIMBATORE REGIONAL PLAN – 2038 VOLUME 2 ERODE SUB REGION DRAFT REPORT Acknowledgements School of Planning and Architecture, Bhopal an Institution of National Importance under the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India heartily acknowledges Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH (German Technical Cooperation) team headed by Mr. Georg Jahnsen, Mr. Felix Knopf, Mr. Abhishek Agarwal, Mrs. Tanaya Saha, Mr. Shriman Narayan, Mr. Kishore for giving us an opportunity to work on the Coimbatore regional plan preparation in Tamil Nadu. We would like to thank the Government of Tamil Nadu, its Secretary Department of Housing and Urban Development and the State Planning Commission for extending their full support in facilitating the whole data collection and discussion process. A special thanks to the all four district collectors: Dr. S. Prabhakar I.A.S. – Erode, Thiru T.N. Hariharan I.A.S. – Coimbatore, Thiru Dr. K.S. Palanisamy I.A.S. – Tiruppur, Tmt.J. Innocent Divya I.A.S. – The nilgiris, for their support and immense effort in coordinating with the concerned line departments for providing data, during their tenure. The contribution of Directorate of Town and Country Planning of Chennai, in this endeavor, in the form of invaluable support and inspiration during the field visit, was commendable. Our sincere thanks all the active Organizations (Profit and Non Profit) like: OlirumErodu Foundation- Erode, TEA-Tiruppur, CII and DIY – Tiruppur, SACON – Coimbatore, WWF-INDIA-Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu Agriculture University – Coimbatore and Tribal Research Centre – The Nilgiris, for giving us an insight about the district and participating in the discussion regarding the future vision for the Coimbatore region, in Tamil Nadu. -

2020102151.Pdf

OFFICERS AND STAFF ASSOCIATED IN PUBLICATION Overall Guidance and Advisors Thiru Mr. AtulAnand, I.A.S., Commissioner, Department of Economics and Statistics, Chennai Technical Guidance Thiru. K. Subramaniyan M.A., M.Phil., B.Ed., Deputy Director of Statistics, Erode Consolidation & Data Processing Unit Thiru.A.Saminathan M.A., Statistical Officer (Computer) Thiru.R.Natarajan M.Sc., M.Phil., Assistant Statistical Investigator, Headquarters Thiru. G.Vengatesh M.Sc., M.Phil., Assistant Statistical Investigator, N.S.S - II PREFACE The publication viz. “District Statistical Hand Book” for the year 2019-20 incorporate multi-various data on the accomplishment made by various central and state government departments, public and private sector undertakings, non-government organizations, etc., relating to the year 2019- 20 in respect of Erode district. The facts and figures furnished in this hand book will serve as a useful apparatus for the planners, policy makers, researchers and also the general Public those who are interested in improved understating of the district at microlevel. I extend my sincere gratitude to Dr. ATUL ANAND, I.A.S., The Commissioner, Department of Economics and Statistics and The District Collector Thiru. C. KATHIRAVAN, I.A.S., for their active and kind hearted support extended for bringing out the important publication encompassing with wide range of data. I also extend my gratefulness to the district heads of various central and state government departments, public and private sector undertakings and also all others those who were extended their support for bringing out this publication. I am pleased to express a word of appreciation to the District Statistical Unit of Erode for their active and energetic involvement extended towards the preparation and publication of this issue.