Management of Major Depressive Disorder(MDD)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Your Depressed Patient Bipolar?

J Am Board Fam Pract: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.271 on 29 June 2005. Downloaded from EVIDENCE-BASED CLINICAL MEDICINE Is Your Depressed Patient Bipolar? Neil S. Kaye, MD, DFAPA Accurate diagnosis of mood disorders is critical for treatment to be effective. Distinguishing between major depression and bipolar disorders, especially the depressed phase of a bipolar disorder, is essen- tial, because they differ substantially in their genetics, clinical course, outcomes, prognosis, and treat- ment. In current practice, bipolar disorders, especially bipolar II disorder, are underdiagnosed. Misdi- agnosing bipolar disorders deprives patients of timely and potentially lifesaving treatment, particularly considering the development of newer and possibly more effective medications for both depressive fea- tures and the maintenance treatment (prevention of recurrence/relapse). This article focuses specifi- cally on how to recognize the identifying features suggestive of a bipolar disorder in patients who present with depressive symptoms or who have previously been diagnosed with major depression or dysthymia. This task is not especially time-consuming, and the interested primary care or family physi- cian can easily perform this assessment. Tools to assist the physician in daily practice with the evalua- tion and recognition of bipolar disorders and bipolar depression are presented and discussed. (J Am Board Fam Pract 2005;18:271–81.) Studies have demonstrated that a large proportion orders than in major depression, and the psychiat- of patients in primary care settings have both med- ric treatments of the 2 disorders are distinctly dif- ical and psychiatric diagnoses and require dual ferent.3–5 Whereas antidepressants are the treatment.1 It is thus the responsibility of the pri- treatment of choice for major depression, current mary care physician, in many instances, to correctly guidelines recommend that antidepressants not be diagnose mental illnesses and to treat or make ap- used in the absence of mood stabilizers in patients propriate referrals. -

Specificity of Psychosis, Mania and Major Depression in A

Molecular Psychiatry (2014) 19, 209–213 & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/14 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Specificity of psychosis, mania and major depression in a contemporary family study CL Vandeleur1, KR Merikangas2, M-PF Strippoli1, E Castelao1 and M Preisig1 There has been increasing attention to the subgroups of mood disorders and their boundaries with other mental disorders, particularly psychoses. The goals of the present paper were (1) to assess the familial aggregation and co-aggregation patterns of the full spectrum of mood disorders (that is, bipolar, schizoaffective (SAF), major depression) based on contemporary diagnostic criteria; and (2) to evaluate the familial specificity of the major subgroups of mood disorders, including psychotic, manic and major depressive episodes (MDEs). The sample included 293 patients with a lifetime diagnosis of SAF disorder, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), 110 orthopedic controls, and 1734 adult first-degree relatives. The diagnostic assignment was based on all available information, including direct diagnostic interviews, family history reports and medical records. Our findings revealed specificity of the familial aggregation of psychosis (odds ratio (OR) ¼ 2.9, confidence interval (CI): 1.1–7.7), mania (OR ¼ 6.4, CI: 2.2–18.7) and MDEs (OR ¼ 2.0, CI: 1.5–2.7) but not hypomania (OR ¼ 1.3, CI: 0.5–3.6). There was no evidence for cross-transmission of mania and MDEs (OR ¼ .7, CI:.5–1.1), psychosis and mania (OR ¼ 1.0, CI:.4–2.7) or psychosis and MDEs (OR ¼ 1.0, CI:.7–1.4). -

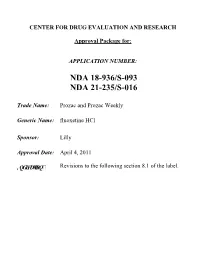

Prozac and Prozac Weekly (Fluoxetine Hcl)

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH Approval Package for: APPLICATION NUMBER: NDA 18-936/S-093 NDA 21-235/S-016 Trade Name: Prozac and Prozac Weekly Generic Name: fluoxetine HCl Sponsor: Lilly Approval Date: April 4, 2011 ,QGLFDWLRQ Revisions to the following section 8.1 of the label. CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: NDA 18-936/S-093 NDA 21-235/S-016 CONTENTS Reviews / Information Included in this NDA Review. Approval Letter X Other Action Letters X Labeling Summary Review X Officer/Employee List Office Director Memo Cross Discipline Team Leader Review Medical Review(s) X Chemistry Review(s) Pharmacology Review(s) Statistical Review(s) Clinical Pharmacology/Biopharmaceutics Review(s) Other Reviews X Proprietary Name Review(s) Administrative/Correspondence Document(s) X CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: NDA 18-936/S-093 NDA 21-235/S-016 APPROVAL LETTER DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Food and Drug Administration Silver Spring MD 20993 NDA 018936/S-091/S-093/S-095 NDA 021235/S-015/S-016/S-017 SUPPLEMENT APPROVAL Eli Lilly & Company Attention: Kevin C. Sheehan, MS, Pharm.D. Manager, Global Regulatory Affairs - US Lilly Corporate Center Indianapolis, IN 46285 Dear Dr. Sheehan: Please refer to your Supplemental New Drug Applications (sNDA) dated and received May 21, 2009 (018936/S-091 and 021235/S-015), November 6, 2009 (018936/S-093 and 021235/S-016), and April 14, 2010 (018936/S-095 and 021235/S-017), submitted under section 505(b) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) for Prozac (fluoxetine hydrochloride) 10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg capsules and Prozac Weekly (fluoxetine hydrochloride) 90 mg delayed-release capsules. -

Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014

Federal Bureau of Prisons Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014 Table of Contents 1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Natural History ................................................................................................................................. 2 Special Considerations ...................................................................................................................... 2 3. Screening ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Screening Questions .......................................................................................................................... 3 Further Screening Methods................................................................................................................ 4 4. Diagnosis ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Depression: Three Levels of Severity ............................................................................................... 4 Clinical Interview and Documentation of Risk Assessment............................................................... -

The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha

t HaRofei LeShvurei Leiv: The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Prof. Reuven Kimelman, Advisor Prof. Zvi Zohar, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts by Ezra Cohen December 2018 Accepted with Highest Honors Copyright by Ezra Cohen Committee Members Name: Prof. Reuven Kimelman Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Lynn Kaye Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Zvi Zohar Signature: ______________________ Table of Contents A Brief Word & Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………... iii Chapter I: Setting the Stage………………………………………………………………………. 1 a. Why This Thesis is Important Right Now………………………………………... 1 b. Defining Key Terms……………………………………………………………… 4 i. Defining Depression……………………………………………………… 5 ii. Defining Halakha…………………………………………………………. 9 c. A Short History of Depression in Halakhic Literature …………………………. 12 Chapter II: The Contemporary Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha…………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 d. Depression & Music Therapy…………………………………………………… 19 e. Depression & Shabbat/Holidays………………………………………………… 28 f. Depression & Abortion…………………………………………………………. 38 g. Depression & Contraception……………………………………………………. 47 h. Depression & Romantic Relationships…………………………………………. 56 i. Depression & Prayer……………………………………………………………. 70 j. Depression & -

Q 2: How Long Should Treatment with Antidepressants Continue in Adults with Depressive Episode/Disorder?

Duration of antidepressant treatment Q 2: How long should treatment with antidepressants continue in adults with depressive episode/disorder? Background Short-term therapy with antidepressant medication is considered standard treatment for acute treatment of moderate to severe depressive episode/disorder. However, because of the long-term nature of depressive disorders, with many patients at substantial risk of later recurrence, there is a need to establish how long, in general, such patients should stay on antidepressants if they have responded to the treatment. Population/Intervention(s)/Comparison/Outcome(s) (PICO) Population: individuals with depressive episode/disorder Interventions: antidepressant medications: tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) and related, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) Comparison: placebo Outcomes: o treatment effectiveness in terms of reduction symptoms o treatment effectiveness in terms of improvement in functioning o acceptability profile List of the systematic reviews identified by the search process INCLUDED IN GRADE TABLES OR FOOTNOTES Deshauer D et al (2008). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for unipolar depression: a systematic review of classic long-term randomized controlled trials. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178:293-1301. 1 Duration of antidepressant treatment Geddes JR et al (2003). Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet, 361:653-61. Hansen R et al (2008). Meta-analysis of major depressive disorder relapse and recurrence with second-generation antidepressants. Psychiatric Services, 59:1121-30. Kaymaz N et al (2008). Evidence that patients with single versus recurrent depressive episodes are differentially sensitive to treatment discontinuation: a meta- analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69:1423-36. -

Which Is It: ADHD, Bipolar Disorder, Or PTSD?

HEALINGHEALINGA PUBLICATION OF THE HCH CLINICIANS’ HANDSHANDS NETWORK Vol. 10, No. 3 I August 2006 Which Is It: ADHD, Bipolar Disorder, or PTSD? Across the spectrum of mental health care, Anxiety Disorders, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders, and Mood Disorders often appear to overlap, as well as co-occur with substance abuse. Learning to differentiate between ADHD, bipolar disorder, and PTSD is crucial for HCH clinicians as they move toward integrated primary and behavioral health care models to serve homeless clients. The primary focus of this issue is differential diagnosis. Readers interested in more detailed clinical information about etiology, treatment, and other interventions are referred to a number of helpful resources listed on page 6. HOMELESS PEOPLE & BEHAVIORAL HEALTH Close to a symptoms exhibited by clients with ADHD, bipolar disorder, or quarter of the estimated 200,000 people who experience long-term, PTSD that make definitive diagnosis formidable. The second chronic homelessness each year in the U.S. suffer from serious mental causative issue is how clients’ illnesses affect their homelessness. illness and as many as 40 percent have substance use disorders, often Understanding that clinical and research scientists and social workers with other co-occurring health problems. Although the majority of continually try to tease out the impact of living circumstances and people experiencing homelessness are able to access resources comorbidities, we recognize the importance of causal issues but set through their extended family and community allowing them to them aside to concentrate primarily on how to achieve accurate rebound more quickly, those who are chronically homeless have few diagnoses in a challenging care environment. -

Drug Repurposing for the Management of Depression: Where Do We Stand Currently?

life Review Drug Repurposing for the Management of Depression: Where Do We Stand Currently? Hosna Mohammad Sadeghi 1,†, Ida Adeli 1,† , Taraneh Mousavi 1,2, Marzieh Daniali 1,2, Shekoufeh Nikfar 3,4,5 and Mohammad Abdollahi 1,2,* 1 Toxicology and Diseases Group (TDG), Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center (PSRC), The Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (TIPS), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran; [email protected] (H.M.S.); [email protected] (I.A.); [email protected] (T.M.); [email protected] (M.D.) 2 Department of Toxicology and Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran 3 Personalized Medicine Research Center, Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran; [email protected] 4 Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center (PSRC) and the Pharmaceutical Management and Economics Research Center (PMERC), Evidence-Based Evaluation of Cost-Effectiveness and Clinical Outcomes Group, The Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (TIPS), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran 5 Department of Pharmacoeconomics and Pharmaceutical Administration, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran * Correspondence: [email protected] † Equally contributed as first authors. Citation: Mohammad Sadeghi, H.; Abstract: A slow rate of new drug discovery and higher costs of new drug development attracted Adeli, I.; Mousavi, T.; Daniali, M.; the attention of scientists and physicians for the repurposing and repositioning of old medications. Nikfar, S.; Abdollahi, M. Drug Experimental studies and off-label use of drugs have helped drive data for further studies of ap- Repurposing for the Management of proving these medications. -

The History of Depression in Neuroscience Morgan Hellyer

The History of Depression in Neuroscience Morgan Hellyer It is not a far stretch to say that philosophers and scientists have been examining depression for hundreds of years. Since around 400 BC when Hippocrates began using the terms “mania and melancholia to describe” depression, people have been attempting to not only quantify the concept of depression, but to also understand and treat it (1). The passing years have seen the rise of many different explanations for depression as well as many different treatments. To this day, there is still no quantifiable cure for depression. Even though some may argue that “depression is a treatable illness,” that is unfortunately a false hope (2). The history of depression proves that despite years of research and investigation and a multitude of treatments, the cure for depression is still only a passing hope that is simply masked by current treatments that dull the symptoms of depression. In order to understand the complexity of depression, and therefore why it cannot be easily treated, it is important to first try to define the complexity that is depression. Depression has been defined in a multitude of different ways; the ancient Greeks believed depression was due to “an imbalance in the body’s four humors . with too much [black bile] resulting in a melancholic state of mind” (3). In contrast, early Christianity said that depression was to be blamed on “the devil and God’s anger for man’s suffering” (3). Towards the end of the nineteenth century however, depression was seen as either a neurological or a psychological disorder (4). -

Bipolar Disorders 100 Years After Manic-Depressive Insanity

Bipolar Disorders 100 years after manic-depressive insanity Edited by Andreas Marneros Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany and Jules Angst University Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland KLUWER ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS NEW YORK, BOSTON, DORDRECHT, LONDON, MOSCOW eBook ISBN: 0-306-47521-9 Print ISBN: 0-7923-6588-7 ©2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers New York, Boston, Dordrecht, London, Moscow Print ©2000 Kluwer Academic Publishers Dordrecht All rights reserved No part of this eBook may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without written consent from the Publisher Created in the United States of America Visit Kluwer Online at: http://kluweronline.com and Kluwer's eBookstore at: http://ebooks.kluweronline.com Contents List of contributors ix Acknowledgements xiii Preface xv 1 Bipolar disorders: roots and evolution Andreas Marneros and Jules Angst 1 2 The soft bipolar spectrum: footnotes to Kraepelin on the interface of hypomania, temperament and depression Hagop S. Akiskal and Olavo Pinto 37 3 The mixed bipolar disorders Susan L. McElroy, Marlene P. Freeman and Hagop S. Akiskal 63 4 Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder Joseph R. Calabrese, Daniel J. Rapport, Robert L. Findling, Melvin D. Shelton and Susan E. Kimmel 89 5 Bipolar schizoaffective disorders Andreas Marneros, Arno Deister and Anke Rohde 111 6 Bipolar disorders during pregnancy, post partum and in menopause Anke Rohde and Andreas Marneros 127 7 Adolescent-onset bipolar illness Stan Kutcher 139 8 Bipolar disorder in old age Kenneth I. Shulman and Nathan Herrmann 153 9 Temperament and personality types in bipolar patients: a historical review Jules Angst 175 viii Contents 10 Interactional styles in bipolar disorder Christoph Mundt, Klaus T. -

Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Practical Assessment and Management MICHAEL G

Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Practical Assessment and Management MICHAEL G. KAVAN, PhD; GARY N. ELSASSER, PharmD; and EUGENE J. BARONE, MD Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, Nebraska Generalized anxiety disorder is common among patients in primary care. Affected patients experience excessive chronic anxiety and worry about events and activities, such as their health, family, work, and finances. The anxiety and worry are difficult to control and often lead to physiologic symptoms, including fatigue, muscle tension, restless- ness, and other somatic complaints. Other psychiatric problems (e.g., depression) and nonpsychiatric factors (e.g., endocrine disorders, medication adverse effects, withdrawal) must be considered in patients with possible generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive behavior therapy and the first-line pharmacologic agents, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, are effective treatments. However, evidence suggests that the effects of cognitive behavior therapy may be more durable. Although complementary and alternative medicine therapies have been used, their effectiveness has not been proven in generalized anxiety disorder. Selection of the most appropriate treatment should be based on patient preference, treatment success history, and other factors that could affect adherence and subsequent effective- ness. (Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(9):785-791. Copyright © 2009 American Academy of Family Physicians.) ▲ Patient information: nxiety disorders, such as generalized GAD is 3.1 percent in population-based sur- -

Adult Depression Clinical Practice Guidelines

NATIONAL CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Adult Depression Clinical Practice Guideline This guideline is informational only. It is not intended or designed as a substitute for the reasonable exercise of independent clinical judgment by practitioners, considering each patient’s needs on an individual basis. Guideline recommendations apply to populations of patients. Clinical judgment is necessary to design treatment plans for individual patients. Approved by the National Guideline Directors February 2012 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................... 1 Guideline Summary...................................................................................................................... 5 Rationale Statements .................................................................................................................. 12 1. First-Line Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) .............................................. 12 2. Hypericum (St. John’s Wort) for MDD............................................................................... 38 3. Antidepressants In Patients With MDD Expressing Suicidal Ideation, Intent, Or Plan...... 44 4. Second-Line Treatment Of MDD ........................................................................................ 48 5. Length Of Treatment With Antidepressants In Patients With MDD................................... 63 6. Follow-Up For Patients In The Acute Phase of Treatment For MDD................................