Framing Arab Spring Conflict: a Visual Analysis of Coverage on Five Transnational Arab News Channels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of US Relations with the Gulf States

The Approaching Turning Point: The Future of U.S. Relations with the Gulf States By F. Gregory Gause, III Brookings Project on U.S. Policy Towards the Islamic World Analysis Paper Number Two, May 2003 1 Executive Summary United States policy toward the Gulf Cooperation Council states (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman) is in the midst of an important change. Saudi Arabia has served as the linchpin of American military and political influence in the Gulf since Desert Storm. It can no longer play that role. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, an American military presence in the kingdom is no longer sustainable in the political system of either the United States or Saudi Arabia. Washington therefore has to rely on the smaller Gulf monarchies to provide the infrastructure for its military presence in the region. The build-up toward war with Iraq has accelerated that change, with the Saudis unwilling to cooperate openly with Washington on this issue. No matter the outcome of war with Iraq, the political and strategic logic of basing American military power in these smaller Gulf states is compelling. In turn, Saudi-American relations need to be reconstituted on a basis that serves the shared interests of both states, and can be sustained in both countries’ political systems. That requires an end to the basing of American forces in the kingdom. The fall of Saddam Hussein will facilitate this goal, allowing the removal of the American air wing in Saudi Arabia that patrols southern Iraq. The public opinion benefits for the Saudis of the departure of the American forces will permit a return to a more normal, if somewhat more distant, cooperative relationship with the United States. -

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS with SUNRISE TV TV Channel List for Printing

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS WITH SUNRISE TV TV channel list for printing Need assistance? Hotline Mon.- Fri., 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. Sat. - Sun. 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. 0800 707 707 Hotline from abroad (free with Sunrise Mobile) +41 58 777 01 01 Sunrise Shops Sunrise Shops Sunrise Communications AG Thurgauerstrasse 101B / PO box 8050 Zürich 03 | 2021 Last updated English Welcome to Sunrise TV This overview will help you find your favourite channels quickly and easily. The table of contents on page 4 of this PDF document shows you which pages of the document are relevant to you – depending on which of the Sunrise TV packages (TV start, TV comfort, and TV neo) and which additional premium packages you have subscribed to. You can click in the table of contents to go to the pages with the desired station lists – sorted by station name or alphabetically – or you can print off the pages that are relevant to you. 2 How to print off these instructions Key If you have opened this PDF document with Adobe Acrobat: Comeback TV lets you watch TV shows up to seven days after they were broadcast (30 hours with TV start). ComeBack TV also enables Go to Acrobat Reader’s symbol list and click on the menu you to restart, pause, fast forward, and rewind programmes. commands “File > Print”. If you have opened the PDF document through your HD is short for High Definition and denotes high-resolution TV and Internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari...): video. Go to the symbol list or to the top of the window (varies by browser) and click on the print icon or the menu commands Get the new Sunrise TV app and have Sunrise TV by your side at all “File > Print” respectively. -

The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television

UC Santa Barbara Global Societies Journal Title The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13s698mx Journal Global Societies Journal, 1(1) Author Elouardaoui, Ouidyane Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television | 100 The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? By: Ouidyane Elouardaoui ABSTRACT Arab media has experienced a radical shift starting in the 1990s with the emergence of a wide range of private satellite TV channels. These new TV channels, such as MBC (Middle East Broadcasting Center) and Aljazeera have rapidly become the leading Arab channels in the realms of entertainment and news broadcasting. These transnational channels are believed by many scholars to have challenged the traditional approach of their government–owned counterparts. Alternatively, other scholars argue that despite the easy flow of capital and images in present Arab television, having access to trustworthy information still poses a challenge due to the governments’ grip on the production and distribution of visual media. This paper brings together these contrasting perspectives, arguing that despite the unifying role of satellite Arab TV channels, in which national challenges are cast as common regional worries, democratization and social development have suffered. One primary factor is the presence of relationships forged between television broadcasters with influential government figures nationally and regionally within the Arab world. -

Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking January 2019 Middle East and North the Role of the Arab States Africa Programme

Briefing Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking January 2019 Middle East and North The Role of the Arab States Africa Programme Yossi Mekelberg Summary and Greg Shapland • The positions of several Arab states towards Israel have evolved greatly in the past 50 years. Four of these states in particular – Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE and (to a lesser extent) Jordan – could be influential in shaping the course of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. • In addition to Egypt and Jordan (which have signed peace treaties with Israel), Saudi Arabia and the UAE, among other Gulf states, now have extensive – albeit discreet – dealings with Israel. • This evolution has created a new situation in the region, with these Arab states now having considerable potential influence over the Israelis and Palestinians. It also has implications for US positions and policy. So far, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE and Jordan have chosen not to test what this influence could achieve. • One reason for the inactivity to date may be disenchantment with the Palestinians and their cause, including the inability of Palestinian leaders to unite to promote it. However, ignoring Palestinian concerns will not bring about a resolution of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, which will continue to add to instability in the region. If Arab leaders see regional stability as being in their countries’ interests, they should be trying to shape any eventual peace plan advanced by the administration of US President Donald Trump in such a way that it forms a framework for negotiations that both Israeli and Palestinian leaderships can accept. Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking: The Role of the Arab States Introduction This briefing forms part of the Chatham House project, ‘Israel–Palestine: Beyond the Stalemate’. -

Non-Indigenous Citizens and “Stateless” Residents in the Gulf

Andrzej Kapiszewski NON-INDIGENOUS CITIZENS AND "STATELESS" RESIDENTS IN THE GULF MONARCHIES. THE KUWAITI BIDUN Since the discovery of oil, the political entities of the Persian Gulf have transformed themselves from desert sheikhdoms into modern states. The process was accompanied by rapid population growth. During the last 50 years, the population of the current Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman1, grew from 4 million in 1950 to 33.4 million in 2004, thus recording one of the highest rates of population growth in the world2. The primary cause of this increase has not been the growth of the indigenous population, large in itself, but the influx of foreign workers. The employment of large numbers of foreigners was a structural imperative for growth in the GCC countries, as oil-related development depended upon the importation of foreign technologies, and reąuired knowledge and skills unfamiliar to the local Arab population. Towards the end of 2004, there were 12.5 million foreigners, 37 percent of the total population, in the GCC states. In Qatar, the UAE, and Kuwait, foreigners constituted a majority. In the United Arab Emirates foreigners accounted for over 80 percent of population. Only Oman and Saudi Arabia managed to maintain a relatively Iow proportion of foreign population: about 20 and 27 percent, respectively. This development has created security, economic, social and cultural threats to the local population. Therefore, to maintain the highly privileged position of the indigenous population and make integration of foreigners with local communities difficult, numerous restrictions were imposed: the sponsorship system, limits on the duration of every foreigner’s stay, curbs on naturalization and on the citizenship rights of those who are naturalized, etc. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2011-43

Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2011-43 PDF version Ottawa, 25 January 2011 Revised lists of eligible satellite services – Annual compilation of amendments 1. In Broadcasting Public Notice 2006-55, the Commission announced that it would periodically issue public notices setting out revised lists of eligible satellite services that include references to all amendments that have been made since the previous public notice setting out the lists was issued. 2. Accordingly, in Appendix 1 to this regulatory policy, the Commission sets out all amendments made to the revised lists since the issuance of Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2010-57. In addition, the lists of eligible satellite services approved as of 31 December 2010 are set out in Appendix 2. 3. The Commission notes that, as set out in Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2010-839, it approved a request by TELUS Communications Company for the addition of 17 new language tracks to Baby TV, a non-Canadian service already included on the lists of eligible satellite services for distribution on a digital basis. Secretary General Related documents • Addition of 17 new language tracks to Baby TV, a service already included on the lists of eligible satellite services for distribution on a digital basis, Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2010-839, 10 November 2010 • Revised lists of eligible satellite services – Annual compilation of amendments, Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2010-57, 4 February 2010 • A new approach to revisions to the Commission’s lists of eligible satellite services, -

Mbc Group Picks Eutelsat's Atlantic Bird™ 7 Satellite

PR/69/11 MBC GROUP PICKS EUTELSAT’S ATLANTIC BIRD™ 7 SATELLITE TO SUPPORT HDTV ROLL-OUT ACROSS THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Paris, 31 October 2011 Eutelsat Communications (Euronext Paris: ETL) and MBC Group announce the signature of a multiyear contract for capacity on Eutelsat’s new ATLANTIC BIRD™ 7 satellite at 7 degrees West. The lease of a full transponder will enable MBC to expand its platform of channels addressing viewers in the Middle East and North Africa, particularly new HD content which the Group is preparing to launch in January 2012. The announcement was made at Digital TV Middle East, the broadcast and broadband conference taking place in Dubai from November 1 to 2. The new contract cements a 20-year relationship between Eutelsat and MBC Group which began in 1991 with the launch of MBC1, the first pan-Arab free-to-air satellite station. Over the past 18 years, MBC has developed a network comprising ten TV channels, two radio stations and a production house to forge a leading media and broadcasting group in the Middle East, among other media platforms such as VOD (shahid.net), SMS and MMS services. The move into HDTV reflects the Group's commitment to delivering the latest technology and superior television content. Launched on September 24, ATLANTIC BIRD™ 7 brings first-class resources to 7 degrees West, an established video neighbourhood delivering Arab and international channels into almost 30 million satellite homes. The satellite’s significant Ku-band resources enable broadcasters to launch new Standard Digital and HD content. -

The Outlook for Arab Gulf Cooperation

The Outlook for Arab Gulf Cooperation Jeffrey Martini, Becca Wasser, Dalia Dassa Kaye, Daniel Egel, Cordaye Ogletree C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1429 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9307-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image: Mideast Saudi Arabia GCC summit, 2015 (photo by Saudi Arabian Press Agency via AP). Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report explores the factors that bind and divide the six Gulf Coop- eration Council (GCC) states and considers the implications of GCC cohesion for the region over the next ten years. -

The Gulf States and the Middle East Peace Process: Considerations, Stakes, and Options

ISSUE BRIEF 08.25.20 The Gulf States and the Middle East Peace Process: Considerations, Stakes, and Options Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Ph.D, Fellow for the Middle East conflict, the Gulf states complied with and INTRODUCTION enforced the Arab League boycott of Israel This issue brief examines where the six until at least 1994 and participated in the nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council— oil embargo of countries that supported 1 Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. In Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates 1973, for example, the president of the (UAE)—currently stand in their outlook and UAE, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, approaches toward the Israeli-Palestinian claimed that “No Arab country is safe from issue. The first section of this brief begins by the perils of the battle with Zionism unless outlining how positions among the six Gulf it plays its role and bears its responsibilities, 2 states have evolved over the three decades in confronting the Israeli enemy.” In since the Madrid Conference of 1991. Section Kuwait, Sheikh Fahd al-Ahmad Al Sabah, a two analyzes the degree to which the six brother of two future Emirs, was wounded Gulf states’ relations with Israel are based while fighting with Fatah in Jordan in 3 on interests, values, or a combination of 1968, while in 1981 the Saudi government both, and how these differ from state to offered to finance the reconstruction of state. Section three details the Gulf states’ Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor after it was 4 responses to the peace plan unveiled by destroyed by an Israeli airstrike. -

Twelve Arab Innovators Become Stars of Science Candidates on Mbc4

TWELVE ARAB INNOVATORS BECOME STARS OF SCIENCE CANDIDATES ON MBC4 Season 7’s Engineering Stage Kicks Off Doha, October 10, 2015 – Twelve of the Arab world’s most promising and remarkable young innovators beat thousands of rival applicants to be selected as candidates on the seventh season of Stars of Science, Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development ‘s (QF) “edutainment reality” TV program on MBC4. This selection concludes the casting phase and marks the onset of the highly competitive engineering stage of the program, in which candidates work tirelessly with mentors to turn their concepts into prototypes; further advancing QF’s mission of unlocking human potential in the next generation of aspiring young science and technology innovators. Chosen candidates have roots in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), Egypt, Algeria, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and Tunisa, reflecting the diversity that has characterized Stars of Science since its inception. Their distinct inventions feature smart technology that can solve problems in fields as varied as medical diagnostics, mobility for the physically challenged, sports, renewable energy and nutrition. On the first three episodes of Stars of Science, thousands of applicants from across the Middle East and North Africa were screened in a multi‐country casting tour by a panel of highly experienced jurors. In the latest Majlis episode, jury members selected twelve of the seventeen shortlisted applicants to become candidates, advancing them to the next phase of the competition, held at Qatar Science & Technology Park, a member of Qatar Foundation. As candidates enter the critical engineering stage, which spans three episodes, they compete against each other in three separate groups labeled; blue, red and purple. -

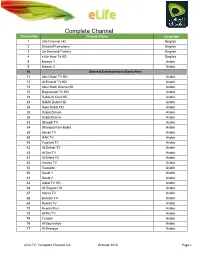

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

MBC Group (Middle East Broadcasting Center)

UAE 방송통신 사업자 보고서 MBC Group (Middle East Broadcasting Center) UAE 최초의 위성 민영 방송사 회사 프로필 상장여부 비상장사 桼1991년영국런던에서설립된 MBC Group 은아랍지역최초의 설립시기 1991 년 위성 민영 방송사로서10TV 개의 채널과 2 개의 라디오 채널 , Sheikh Waleed Al Ibrahim 주요 인사 회장 다큐제작사, 온라인플랫폼 등을 운영 중임 TV채널 10 개 TV 채널 , 2 개 라디오 채널 PO Box 76267, Dubai 주소 - MBC Group은 아랍 최초로 24 시간 무료 위성 방송을 Media City, Dubai, UAE 전화 +971 4 390 9971 제공하고 있음 매출 N/A 직원 수 약1,000 명 (‘10) - MBC Group은 회장 겸 CEO 인 Sheikh Waleed Al Ibrahim 과 홈페이지 www.mbc.net 사우디아라비아 왕실이 주요 주주이며, 자세한 지분 내역은 회사 연혁 공개되지 않음 2011HD 방송 시작 2008 타 중동 국가 진출 200324 시간 무료 영화 채널 런칭 桼MBC Group은 24 시간 뉴스 , 영화 , 드라마 , 여성 전용 , 유아 2002 두바이로 본사 이전 엔터테인먼트 등 다양한 채널을 운용하고 있으며, 시청자들에게 1994 사우디아라비아 진출 1991 설립 긍정적인 호응을 얻고 있음 -2011년 기준 주요채널시청률은 MBC 2 51.5%, MBC Action 47%, MBC 1 39.5% 로 타 방송사업자 대비 높은 시청률을 기록하고 있음 桼또한, 아랍 지역 대표 포털 사이트인MBC net 운영을 통해 스포츠 , 엔터테인먼트, 영화 , 음악 콘텐츠를 제공하고 있음 - 2011년 7 월 ,Shahid.net 서비스를 개시하여 , 온라인 TV 사업을 강화하고 있음에 따라MBC Group 의 UAE TV 시장에서의 입지가 더욱 견고해질 전망임 桼2011년 7 월 7 개채널에서 HD 방송을시작하였음 UAE TV시청율 (2011) 주요 채널 현황 순위 채널 %%% 장르 채널명 1 MBC 2 51.5 종합 엔터테인먼트 MBC 1 2 MBC Action 47 여성 엔터테인먼트 MBC 4 3 MBC 1 39.5 유아 엔터테인먼트 MBC 3 4 Dubai TV 32.7 5 Abu Dhabi Al Oula 32.6 영화 MBC 2, MBC Max, MBC Persia, MBC Action 6 MBC 4 32.1 뉴스 Al Arabiya 7 Al Jazeera 30.4 음악 Wanasah 8 Al Arabiya 29.1 9 Fox Movies 24.7 드라마 MBC Drama 10 Zee TV 24.6 라디오 MBC FM, Panorama FM - 1 - 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지 UAE 방송통신 사업자 보고서 □□□ 비전 및 전략 桼桼桼 비전 o정보 , 상호 작용 및 엔터테인먼트를 통해 아랍 세계의 삶을 풍요롭게 하는 글로벌 미디어 Group 桼桼桼 전략 o TV 와 온라인을 통한 혁신적인 정보 및 엔터테인먼트의 멀티 플랫폼 제공 o글로벌주요 TV 프로그램상용을통한 TV 시청점유율상승 □□□ 조직 현황 桼桼桼