CANADIAN CENTRE for POLICY ALTERNATIVES MANITOBA OFFICE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debates Proceedings

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker The Honourable Peter Fox Vol.XVlll No.98 2:30p.m., Monday, July5th, '1971. ThirdSession,29th Legislature. Printed by R. S. Evans - Queen's Printer for Province of Manitoba I I ELECTORAL DIVISION NAME ADDRESS ARTHUR J. Douglas Watt Reston, Manitoba ASSINIBOIA Steve Patrick 10 Red Robin Place, Winnipeg 12 BIRTLE-RUSSELL Harry E. Graham Binscarth, Manitoba BRANDON EAST Hon. Leonard S. Evans Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 BRANDON WEST Edward McGill 2228 Princess Ave., Brandon, Man. BURROWS Hon. Ben Hanuschak Legislative Building, Winnipeg 1 CHARLESWOOD Arthur Moug 29 Willow Ridge Rd., Winnipeg 20 CHURCHILL Gordon Wilbert Beard 148 Riverside Drive, Thompson, Man. CRESCENTWOOD Cy Gonick 115 Kingsway, Winnipeg 9 DAUPHIN Hon. Peter Burtniak Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 ELMWOOD Hon. Russell J. Doern Legislative Building, Winnipeg 1 EMERSON Gabriel Girard 25 Lamond Blvd., St. Boniface 6 FLIN FLON Thomas Barrow Cranberry Portage, Manitoba FORT GARRY L. R. (Bud) Sherman B6 Niagara St., Winnipeg 9 - FORT ROUGE Mrs. Inez Trueman 179 Oxford St., Winnipeg 9 GIMLI John C. Gottfried 44 - 3rd Ave., Gimli, Man. GLADSTONE James Robert Ferguson Gladstone, Manitoba INKSTER Hon. Sidney Green, O.C. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 KILDONAN Hon. Peter Fox 627 Prince Rupert Ave., Winnipeg 15 LAC DU BONNET Hon. Sam Uskiw Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 LAKESIDE Harry J. Enns Woodlands, Manitoba LA VERENDRYE Leonard A. Barkman Box 130, Steinbach, Man. LOGAN William Jenkins 1287 Alexander Ave., Winnipeg 3 MINNEDOSA Walter Weir Room 250, Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 MORRIS Warner H. Jorgenson Box 185, Morris, Man. OSBORNE Ian Turnbull 284 Wildwood Park, Winnipeg 19 PE MB INA George Henderson Manitou, Manitoba POINT DOUGLAS Donald Malinowski 361 Burrows Ave., Winnipeg 4 PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE Gordon E. -

Debates Proceedings

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker The Honourable Peter Fox Vol. XIX No. 76 10:00a.m., Friday, May 12tll, 1972. Fourth Session, 29th Legislature. Printed by R. S. Evans- Queen's Printer for Province of Manitoba Political Electoral Division Name Address Affiliation ARTHUR J. Douglas Watt P.C. Reston, Manitoba ASSINIBOIA Steve Patrick Lib. 10 Red Robin Place, Winnipeg 12 Bl RTLE-RUSSELL Harry E. Graham P.C. Binscarth, Manitoba BRANDON EAST Hon. Leonard S. Evans N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 BRANDON WEST Edward McGill P.C. 2228 Princess Ave., Brandon, Man. BURROWS Hon. Ben Hanuschak N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 CHARLESWOOD Arthur Moug P.C. 29 Willow Ridge Rd., Winnipeg 20 CHURCHILL Gordon Wilbert Beard lnd. 148 Riverside Drive, Thompson, Man. CRESCENTWOOD Cy Gonick N.D.P. 1- 174 Nassau Street, Winnipeg 13 DAUPHIN Hon. Peter Burtniak N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 ELMWOOD Hon. RussellJ. Doern N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 EMERSON Gabriel Girard P.C. 25 Lomond Blvd., St. Boniface 6 FLIN FLON Thomas Barrow N.D.P. Cranberry Portage, Manitoba FORT GARRY L. R. (Bud) Sherman P.C. 86 Niagara St., Winnipeg 9 FORT ROUGE Mrs. lnez Trueman P.C. 179 Oxford St., Winnipeg 9 GIMLI John C. Gottfried N.D.P. 44- 3rd Ave., Gimli Man. GLADSTONE James Robert Ferguson P.C. Gladstone, Manitoba INKSTER Sidney Green, Q.C. N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 KILDONAN Hon. Peter Fox N.D.P. 244 Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 LAC DU BONNET Hon. Sam Uskiw N.D.P. -

2. the Capital Budget Winnipeg's

Contributors This guide is the first Betty Braaksma step in a four-part Manitoba Library Association Canadian Centre for Policy Marianne Cerilli Social Planning Council of Winnipeg Alternatives-Manitoba Lynne Fernandez (CCPA-Mb) project to Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Manitoba engage Winnipeggers in Jesse Hajer Canadian Community Economic Development municipal decision-making. Network Step Two is a survey of George Harris key municipal spending Ian Hudson Department of Economics areas, Step Three will be an University of Manitoba in-depth response to this Bob Kury spring’s 2008 Operating Dennis Lewycky CCPA Board Member Budget, and Step Four will Lindsey McBain be our Alternative City Canadian Community Economic Development Network Budget, to be released in Tom Simms the fall of 2008. Many thanks to Liz Carlye of the Canadian Federation of Students CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY (Manitoba) and Doug Smith for their ALTERNATIVES-MB help with production. 309-323 Portage Ave. Winnipeg, MB Canada R3B 2C1 ph: (204) 927-3200 fax: (204) 927-3201 [email protected] www.policyalternatives.ca A Citizens’ Guide to Understanding Winnipeg’s City Budgets 1 Introduction innipeg City Council spends more than one billion dollars a year running our city. From the moment we get up in the morning, most of us benefit from the Wservices that our taxes provide. We wash up with water that is piped in through a city-built and operated water works, we walk our children to school on city sidewalks, go to work on city buses, drive on city streets that have been cleared of snow by the City. -

DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

Second Session - Fortieth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Official Report (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable Daryl Reid Speaker Vol. LXV No. 104 - 1:30 p.m., Monday, September 9, 2013 ISSN 0542-5492 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Fortieth Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation ALLAN, Nancy, Hon. St. Vital NDP ALLUM, James Fort Garry-Riverview NDP ALTEMEYER, Rob Wolseley NDP ASHTON, Steve, Hon. Thompson NDP BJORNSON, Peter, Hon. Gimli NDP BLADY, Sharon Kirkfield Park NDP BRAUN, Erna Rossmere NDP BRIESE, Stuart Agassiz PC CALDWELL, Drew Brandon East NDP CHIEF, Kevin, Hon. Point Douglas NDP CHOMIAK, Dave, Hon. Kildonan NDP CROTHERS, Deanne St. James NDP CULLEN, Cliff Spruce Woods PC DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk NDP DRIEDGER, Myrna Charleswood PC EICHLER, Ralph Lakeside PC EWASKO, Wayne Lac du Bonnet PC FRIESEN, Cameron Morden-Winkler PC GAUDREAU, Dave St. Norbert NDP GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Liberal GOERTZEN, Kelvin Steinbach PC GRAYDON, Cliff Emerson PC HELWER, Reg Brandon West PC HOWARD, Jennifer, Hon. Fort Rouge NDP IRVIN-ROSS, Kerri, Hon. Fort Richmond NDP JHA, Bidhu Radisson NDP KOSTYSHYN, Ron, Hon. Swan River NDP LEMIEUX, Ron, Hon. Dawson Trail NDP MACKINTOSH, Gord, Hon. St. Johns NDP MAGUIRE, Larry Arthur-Virden PC MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood NDP MARCELINO, Flor, Hon. Logan NDP MARCELINO, Ted Tyndall Park NDP MELNICK, Christine, Hon. Riel NDP MITCHELSON, Bonnie River East PC NEVAKSHONOFF, Tom Interlake NDP OSWALD, Theresa, Hon. Seine River NDP PALLISTER, Brian Fort Whyte PC PEDERSEN, Blaine Midland PC PETTERSEN, Clarence Flin Flon NDP REID, Daryl, Hon. Transcona NDP ROBINSON, Eric, Hon. Kewatinook NDP RONDEAU, Jim, Hon. -

COUNCIL of the CITY of WINNIPEG Wednesday, February 24, 2010

COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF WINNIPEG Wednesday, February 24, 2010 The Council met at 9:35 a.m. The Clerk advised the Speaker that a quorum was present. The Speaker called the meeting to order. The opening prayer was read by Councillor Swandel. ROLL CALL Clerk: Mr. Speaker, Councillor Lazarenko, His Worship Mayor Katz; Councillors Browaty, Clement, Fielding, Gerbasi, Nordman, Orlikow, Pagtakhan, Smith, Swandel, Thomas, Vandal, Wyatt. INTRODUCTION AND WELCOME OF GUESTS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS Mr. Speaker: Thank you. We have Pages. Nick Bruneau of Garden City Collegiate, resides in the Mynarski Ward. Welcome. Marianne Cerilli; an instructor with Red River Community College together with her students from the Red River College in the Economic Development Program. Are you there Marianne? They're not here yet? Thank you. Mr. Mayor. Mayor Katz: Mr. Speaker, I thank you. Just a brief comment. First of all, congratulating all of our Canadian Athletes performing in the Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Whistler, etc. Specifically, obviously the ones from Manitoba. A big congratulations to Jon Montgomery who won gold medal from Russell, Manitoba, as well as the Athletes from the balance of Manitoba and Winnipeg who continue to strive to do their best to represent our Country and make us proud, and I think it's been exciting for all Canadians who have had the opportunity to participate in the impromptu singing of “Oh Canada” during certain events, again, a phenomenal job. Thank you, Mr. Speaker. Mr. Speaker: Thank you, Mr. Mayor. Councillor Pagtakhan, just a minute. MINUTES Councillor Nordman moves that the Minutes of the meeting held on January 27, 2010, be taken as read and confirmed. -

Annual Report 2007-2008

Social Planning Council of Winnipeg est. 1919 R Raising Community Awareness 2007/08 Annual Report for 89 Years! 412 McDermot Avenue Winnipeg MB, R3A 0A9 www.spcw.mb.ca Just Responsive Caring Action Oriented Leadership RaISING COMMUNITY AWARENESS Resources Grass roots Developing Table of Contents President’s Report 1 CSI Site Synopsis 2 Executive Director’s Report 3 Urban Inuit Project 4 Campaign 2000 Continues Report 5 Falling Fortunes 6 Poverty Advisory Committee Report 7 Homeless Individuals and Families Information System 8 Committee for the Elimination of Racism and Discrimination Report 9 2007 Manitoba Child and Family Poverty Report Card 10 Environment Committee Report 11 Raise the Rates 12 Auditor’s Report 13 Financial Report 14 Raise: to give rise to; to bring about Student’s Report 15 Meeting Strategic Priorities 16 Staff, Board, Committee Chairs 17 Staff, Board, Committee Chairs 18 Page i Presidents Report It was an honor to be asked to serve as President of the Social Planning Council of Winnipeg (SPC) this past year. Even before arriving in Winnipeg, I had a sense of appreciation for the important work being done at the SPC. The agency has an accomplished history that I am happy to have been a part of. The work at SPC would not be possible without a group of passionate people to contribute to each project and event. I extend much thanks to Wayne Helgason, the staff, and the Board members who served throughout the year. I would like to express great appreciation to the Committee Chairs for their ideas and enthusiasm towards SPC’s various projects, efforts, and endeavours. -

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

. Second Session - Thirty-Sixth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable Louise M Dacquay Speaker Vol. XLVI No. 42A- 1:30 p.m., Wednesday, May 29, 1996 ISSN 0542-5492 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-Sixth Legislature Members, Constituencies and Political Affiliation Name Constituency bJ:ty ASHTON, Steve Thompson N.D.P. BARRETT, Becky Wellington N.D.P. CERILLI, Marianne Radisson N.D.P. CHOMIAK, Dave Kildonan N.D.P. CUMMINGS, Glen, Hon. Ste. Rose P.C. DACQUAY, Louise, Hon. Seine River P.C. DERKACH, Leonard, Hon. Rob lin-Russell P.C. DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk N.D.P. DOER, Gary Concordia N.D.P. DOWNEY, James, Hon. Arthur-Virden P.C. DRIEDGER, Albert, Hon. Steinbach P.C. DYCK, Peter Pembina P.C. ENNS, Harry, Hon. Lakeside P.C. ERNST, Jim, Hon. Charleswood P.C. EVANS, Clif Interlake N.D.P. EVANS, Leonard S. Brandon East N.D.P. FILMON, Gary, Hon. Tuxedo P.C. FINDLAY, Glen, Hon. Springfield P.C. FRIESEN, Jean Wolseley N.D.P. GAUDRY, Neil St. Boniface Lib. GILLESHAMMER, Harold, Hon. Minnedosa P.C. HELWER, Edward Gimli P.C. HICKES, George Point Douglas N.D.P. JENNISSEN, Gerard Flin Flon N.D.P. KOWALSKI, Gary The Maples Lib. LAMOUREUX, Kevin Inkster Lib. LATHLIN, Oscar The Pas N.D.P. LAURENDEAU, Marcel St. Norbert P.C. MACKINTOSH, Gord St. Johns N.D.P. MALOWA Y, Jim Elmwood N.D.P. MARTINDALE, Doug Burrows N.D.P. McALPINE, Gerry Sturgeon Creek P.C. McCRAE, James, Hon. Brandon West P.C. -

Manitoba and Saskatchewan Elections: Broken Electoral Destinies?

The 2007 Manitoba and Saskatchewan elections: Broken Electoral Destinies? Florence Cartigny Doctoral Candidate – University of Bordeaux 3, France DRAFT VERSION Abstract: Both Saskatchewan and Manitoba have traditionally been seen as social democratic provinces. But, over the past decades, there has been an increasing convergence in policy solutions and as a consequence the platforms of political parties have become more and more similar. What is the impact of this convergence on the 2007 provincial election in Saskatchewan and in Manitoba? In November 2007, the Saskatchewan NDP lost the election, thus ending a 16-year NDP reign while in May 2007, the Manitoba NDP in power for 7 years was re-elected. The Saskatchewan Party won 38 seats out of 58 (65%), thus gaining 8 seats. In Manitoba, the NDP took 36 of 57 seats (63%). And yet, many commonalities appear in the policy platforms of those political parties. In Manitoba, the NDP focused on universal health care, education, tax cuts, public safety, money for highways and on reducing pollution. But in Saskatchewan promises were very similar for the two rivals. Indeed, both the NDP and the Saskatchewan Party made promises on improved health care and tuition breaks for post- secondary students, on recruiting medical professionals and on reducing greenhouse gases. But those common points are not necessarily social democratic ideals. Does this shift in electoral preferences signal the end of a common social democratic destiny between Manitoba and Saskatchewan? Do those election results signal an ideological continuum in Manitoba and a rupture in Saskatchewan? To answer those questions, policy platforms and debates will be analyzed in depth. -

The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left During the Long Sixties

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-13-2019 1:00 PM 'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties David G. Blocker The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Fleming, Keith The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © David G. Blocker 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons Recommended Citation Blocker, David G., "'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6554. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6554 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Abstract The Sixties were time of conflict and change in Canada and beyond. Radical social movements and countercultures challenged the conservatism of the preceding decade, rejected traditional forms of politics, and demanded an alternative based on the principles of social justice, individual freedom and an end to oppression on all fronts. Yet in Canada a unique political movement emerged which embraced these principles but proposed that New Left social movements – the student and anti-war movements, the women’s liberation movement and Canadian nationalists – could bring about radical political change not only through street protests and sit-ins, but also through participation in electoral politics. -

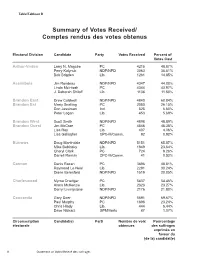

Summary of Votes Received/ Comptes Rendus Des Votes Obtenus

Table/Tableau D Summary of Votes Received/ Comptes rendus des votes obtenus Electoral Division Candidate Party Votes Received Percent of Votes Cast Arthur-Virden Larry N. Maguire PC 4215 48.87% Perry Kalynuk NDP/NPD 3063 35.51% Bob Brigden Lib. 1281 14.85% Assiniboia Jim Rondeau NDP/NPD 4347 44.00% Linda McIntosh PC 4344 43.97% J. Deborah Shiloff Lib. 1136 11.50% Brandon East Drew Caldwell NDP/NPD 4840 60.84% Brandon Est Marty Snelling PC 2080 26.15% Don Jessiman Ind. 525 6.60% Peter Logan Lib. 453 5.69% Brandon West Scott Smith NDP/NPD 4898 48.89% Brandon Ouest Jim McCrae PC 4546 45.38% Lisa Roy Lib. 407 4.06% Lisa Gallagher CPC-M/Comm. 92 0.92% Burrows Doug Martindale NDP/NPD 5151 65.87% Mike Babinsky Lib. 1849 23.64% Cheryl Clark PC 724 9.26% Darrell Rankin CPC-M/Comm. 41 0.52% Carman Denis Rocan PC 3698 48.81% Raymond Le Neal Lib. 2291 30.24% Diane Beresford NDP/NPD 1519 20.05% Charleswood Myrna Driedger PC 5437 54.46% Alana McKenzie Lib. 2323 23.27% Darryl Livingstone NDP/NPD 2176 21.80% Concordia Gary Doer NDP/NPD 5691 69.67% Paul Murphy PC 1898 23.24% Chris Hlady Lib. 444 5.44% Dave Nickarz GPM/Verts 87 1.07% Circonscription Candidat(e) Parti Nombre de voix Pourcentage électorale obtenues des suffrages exprimés en faveur du (de la) candidat(e) 8 Statement of Votes/Relevé des suffrages Electoral Division Candidate Party Votes Received Percent of Votes Cast Dauphin-Roblin Stan Struthers NDP/NPD 5596 55.44% Lorne Boguski PC 4001 39.64% Doug McPhee MP 455 4.51% Elmwood Jim Maloway NDP/NPD 5176 62.13% Elsie Bordynuik PC 2659 31.92% Cameron Neumann LPM/PLM 320 3.84% James Hogaboam CPC-M/Comm. -

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

Fourth Session - Thirty-Sixth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Official Report (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable Louise M. Dacquay Speaker Vol. XLVIII No. 24 - 1:30 p.m., Wednesday, March 25, 1998 ISSN 0542-5492 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-Sixth Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation ASHTON, Steve Thompson N.D.P. BARRETI, Becky Wellington N.D.P. CERILLI, Marianne Radisson N.D.P. CHOMIAK, Dave Kildonan N.D.P. CUMMINGS, Glen, Hon. Ste. Rose P.C. DACQUAY, Louise, Hon. Seine River P.C. DERKACH, Leonard, Hon. Rob lin-Russell P.C. DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk N.D.P. DOER, Gary Concordia N.D.P. DOWNEY, James, Hon. Arthur-Virden P.C. DRIEDGER, Albert Steinbach P.C. DYCK, Peter Pembina P.C. ENNS, Harry, Hon. Lakeside P.C. EVANS, Clif Interlake N.D.P. EVANS, Leonard S. Brandon East N.D.P. FAURSCHOU, David Portage Ia Prairie P.C. FILMON, Gary, Hon. Tuxedo P.C. FINDLAY, Glen, Hon. Springfield P.C. FRIESEN, Jean Wolseley N.D.P. GAUDRY, Neil St. Boniface Lib. GILLESHAMMER, Harold, Hon. Minnedosa P.C. HEL WER, Edward Gimli P.C. HICKES, George Point Douglas N.D.P. JENNISSEN, Gerard Flin Flon N.D.P. KOWALSKI, Gary The Maples Lib. LAMOUREUX, Kevin Inkster Lib. LATHLIN, Oscar The Pas N.D.P. LAURENDEAU, Marcel St. Norbert P.C. MACKINTOSH, Gord St. Johns N.D.P. MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood N.D.P. MARTINDALE, Doug Burrows N.D.P. McALPINE, Gerry Sturgeon Creek P.C. McCRAE, James, Hon. Brandon West P.C. McGIFFORD, Diane Osborne N.D.P. -

To the Honourable the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba

TO THE HONOURABLE THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MANITOBA Your Standing Committee on SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT presents the following as its Second Report. Meetings Your Committee met on September 5, 2013 at 6:00 p.m. in Room 254 of the Legislative Building. Matters under Consideration • Bill (No. 2) – The Highway Traffic Amendment Act (Respect for the Safety of Emergency and Enforcement Personnel)/Loi modifiant le Code de la route (sécurité du personnel d'urgence et des agents d'exécution de la loi) • Bill (No. 31) – The Workplace Safety and Health Amendment Act/Loi modifiant la Loi sur la sécurité et l'hygiène du travail • Bill (No. 34) – The Property Registry Statutes Amendment Act/Loi modifiant diverses lois relatives à l'Office d'enregistrement des titres et des instruments • Bill (No. 37) – The Emergency Measures Amendment Act/Loi modifiant la Loi sur les mesures d'urgence • Bill (No. 40) – The Residential Tenancies Amendment Act/Loi modifiant la Loi sur la location à usage d'habitation • Bill (No. 208) – The Universal Newborn Hearing Screening Act/Loi sur le dépistage systématique des déficiences auditives chez les nouveau-nés • Bill (No. 211) – The Personal Information Protection and Identity Theft Prevention Act/Loi sur la protection des renseignements personnels et la prévention du vol d'identité Committee Membership • Hon. Mr. ASHTON • Ms. BLADY • Mr. CULLEN • Mrs. DRIEDGER • Mr. EICHLER • Mr. GAUDREAU • Hon. Ms. HOWARD • Mr. JHA • Hon. Mr. RONDEAU • Mrs. ROWAT • Hon. Mr. STRUTHERS Your Committee elected Mr. JHA as the Chairperson. Your Committee elected Ms. BLADY as the Vice-Chairperson. Substitutions received during committee proceedings: • Mr.