DOCUMENT RESUME ED 045 679 TE 002 192 TITLE Folklore in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playbook Games (PDF)

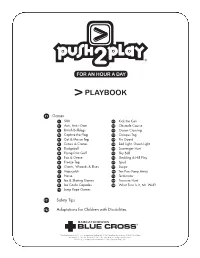

® PLAYBOOK V P1 Games P1 500 P11 Kick the Can P1 Anti, Anti i-Over P12 Obstacle Course P2 British Bulldogs P13 Ocean Crossing P2 Capture the Flag P13 Octopus Tag P3 Cat & Mouse Tag P14 Pin Guard P3 Crows & Cranes P14 Red Light, Green Light P4 Dodgeball P15 Scavenger Hunt P4 Flying Disc Golf P15 Sky Ball P5 Fox & Geese P16 Sledding & Hill Play P6 Freeze Tag P17 Spud P6 Giants, Wizards & Elves P17 Swipe P7 Hopscotch P18 Ten Pass Keep Away P7 Horse P19 Terminator P8 Ice & Skating Games P19 Treasure Hunt P9 Ice Castle Capades P20 What Time Is It, Mr. Wolf? P10 Jump Rope Games P21 Safety Tips P23 Adaptations for Children with Disabilities ®Saskatchewan Blue Cross is a registered trade-mark of the Canadian Association of Blue Cross Plans, used under licence by Medical Services Incorporated, an independent licensee. Push2Play is a registered trade-mark of Saskatchewan Blue Cross. HOW TO PLAY: Choose 1 player to be the first thrower. The rest of the players should be 15 to 20 steps away from Players the thrower. 3 or more The thrower shouts out a number and throws the ball toward the group Equipment so everyone has an equal chance of catching it. Ball The player who catches the ball gets the number of points the thrower shouted. The thrower continues to throw the ball until another player makes enough catches to add up to 500 points. This player now becomes the thrower. CHANGE THE FUN: If a player drops the ball, the points shouted out by the thrower are taken away from the player’s score. -

2021 Summer Day Camp @ - Elkhart Elementary

2021 SUMMER DAY CAMP @ - ELKHART ELEMENTARY THIS WEEK AT THE Y WEEKLY THEME: BACK TO THE FUTURE CAMPERS & FAMILIES - WEEK OF: May 31st-June 4th NO YMCA on Monday, May 31st. Memorial Day! FIELD TRIPS & SPECIAL EVENTS: June 1st - First Day of Camp! Everyday-Please make sure to bring a Mask, Lunch, 2 Snacks, Water Bottle, Closed Toed Shoes and Sunscreen. Friday– Magic Rob SITE HOURS CONTACT US 6:30 AM—6:00 PM Director - Maria Leon [email protected] Assistant Director - Carmen VISIT US ONLINE https://www.denverymca.org/programs/youth-programs/summer-day-camp WHAT TO BRING EVERYDAY Water Bottle, Shoes w/ closed toes, Sunscreen, Lunch, AM & PM Snacks MONDAY WEDNESDAY FRIDAY TUESDAY THURSDAY 6:30-8:30 6:30-8:30 6:30-8:30 6:30-8:30 Open Camp Stations Open Camp Stations Open Camp Stations Open Camp Stations NO CAMP Coloring, Coloring 9:00 Coloring, Coloring, - CAMP Building Games Building Games - Building Games Building Games 6:30 Board Games Board Games Board Games Board Games PRE CAMP OPENING CAMP OPENING CAMP OPENING & AM SNACK & AM SNACK & AM SNACK CAMP OPENING CAMP OPENING & AM SNACK AM ROTATIONS & AM SNACK AM ROTATIONS 9:00-9:30AM 9:00-9:30AM AM ROTATIONS AM ROTATIONS 9:00-9:30AM Snack and Camp Opening 9:00-9:30AM Snack and Camp Opening NO CAMP Snack and Camp Opening 9:45-11:45 Snack and Camp Opening 9:45-11:45 9:45-11:45 Craft– Pictures Frames 9:45-11:45 Cooking– Root Beer Floats Craft– CD Disco Ball Gym– Freeze Dance Craft– Loom Bracelets 12:00 Gym– Brake Dance — Outside– Dress up Relay Gym– Double Dutch Gym– 60– Second Contest Objects -

J.A.M. (Jump and Move): Practical Ideas for JR4H Heart Links Instant

J.A.M. (Jump And Move): Practical Ideas for JR4H Chad Triolet – [email protected] Chesapeake Public Schools 2011 NASPE Elementary Physical Education Teacher of the Year www.PErocks.com www.noodlegames.net www.youtube.com/user/NoodleGames Heart Links Heart Links are a great way to make some connections for students regarding fundraising and the importance of exercise in building a strong and healthy heart. We use this activity during our Jump Rope for Heart week as a “rest station”. Students complete one heart link each class period and are asked to write down one thing they can do to be heart healthy or a heart healthy slogan. They can decorate them if they would like and then they place them in a basket so that the links can be put together. During class, we connect some of the links then talk about the links at the end of the class as a culminating discussion about the importance of fundraising and exercise. Fundraising – Sometimes a small amount of money does not seem like it makes a difference but if you use the heart chain that is created as an example, students realize that when the links are added together they make a huge chain that goes around the gym. So, every little bit of money collected, no matter how small, adds up and can make a difference. Exercise – In much the same way, daily exercise doesn’t seem like it would have a big effect on how healthy your heart can be. The visual of the heart chain helps the students understand that if you exercise each day, it adds up and builds a strong and healthy heart. -

2 – 3 Wall Ball Only a Jelly Ball May Be Used for This Game. 1. No Games

One Fly Up Switch 5. After one bounce, receiving player hits the ball 1 – 2 – 3 Wall Ball Use a soccer ball only. Played in Four Square court. underhand to any another square. No “claws” (one hand Only a jelly ball may be used for this game. 1. The kicker drop kicks the ball. on top and one hand on the bottom of the ball). 2. Whoever catches the ball is the next kicker. 1. Five players play at a time, one in each corner and one 6. Players may use 1 or 2 hands, as long as it is underhand. 1. No games allowed that aim the ball at a student standing 3. Kicker gets 4 kicks and if the ball is not caught, s/he in the middle of the court. 7. Players may step out of bounds to play a ball that has against the wall. picks the next kicker. bounced in their square, but s/he may not go into 2. No more than three players in a court at one time. 2. When the middle person shouts “Switch!” in his/her another player’s square. 3. First person to court is server and number 1. No “first loudest voice, each person moves to a new corner. Knock Out 8. When one player is out, the next child in line enters at serves”. 3. The person without a corner is out and goes to the end Use 2 basketballs only for this game. the D square, and the others rotate. 4. Ball may be hit with fist, open palm, or interlocked of the line. -

NONCOMPETE GAMES 2018.Cdr

WHY NONCOMPETITIVE RECREATION? THE ANSWER: COOPERATIVE GAMES The concept behind noncompetitive recreation can be either hard to understand or hard to accept or both! So who needs games nobody loses? Too often games have become rigid, judgmental, too highly organized and excessively goal-oriented. Have you seen children left out, eliminated to sit out, always chosen last, rejected and wondered why? Many children quit organized sports early because of pressure or they don’t feel they are good enough. We need to find ways for plain old fashioned fun Cooperative games offer a positive alternative. These interactive games provide opportunities for challenge, stimulation and success while eliminating the fear of failure. They foster greater communication, trust, social interaction, acceptance and sharing. Children play with one another instead of against one another. As partners instead of opponents we compete against the limits of our own abilities instead of against each other. Everybody must cooperate in order to accomplish the goals or meet the challenge. The beauty of the games lies in their versatility and adaptability. In most cases there is inexpensive or no equipment necessary. Rules need not to be strictly adhered to. Instead of being eliminated, players change roles or sides or teams and keep playing. Players can work out their own details. These games can reaffirm a child’s confidence in their selves and help them in their willingness to try new experiences. You can bring out creativity and even a boldness they never knew they had. The games can help build a “WHY NOT?” Attitude. NEVER lose sight of the fact that the primary reason children play games is to have fun. -

The Woodland Park Physical Education Program Develops Motor Skills and Teachers Concepts of Movement Through a Wide Variety of Activities

Physical Education Curriculum- 2014-2015 The Woodland Park Physical Education Program Develops motor skills and teachers concepts of movement through a wide variety of activities. Students experience enjoyment and a heightened awareness of the benefits of movement and fitness. This is the foundation for a lifetime of activity and wellness. Physical Education is for all students. Our program focuses on individual learning needs, thereby developing confidence and self-esteem as students strive to perform at their individual best. By actively participating, students learn effective stress management skills that enhance physical and emotional wellbeing. This self-discovery educates the students about their strengths and aids them in setting realistic goals. Through participation in our Physical Education Program, social skills such as effective communication, conflict resolution, tolerance and cooperative group plat are developed. All of these aspects combined help our students become well rounded. Our district’s commitment is to empower students to choose lifetime physical activities that lead to a more productive healthy lifestyle. Physical Education Curriculum- 2014-2015 Pacing Guide Content Area: Physical Education Grade Level: Kindergarten Unit Title: Safety Rules and Requirements/ Classroom Set-Up Two Weeks Unit Title: Body Awareness/ Movement and Skills Two Weeks Unit Title: Ball Manipulation Two Weeks Unit Title: Fitness-Gram Activities Three Weeks- Fall, Winter, Spring Unit Title: Obstacle Course Two Weeks Unit Title: Jump Rope for -

Jacks and Other Dexterity Games in Children and Their Parents

Special article Arch Argent Pediatr 2019;117(6):405-410 / 405 Jacks and other dexterity games in children and their parents Alfredo Eymann, M.D.a, Alejo Cavadas, Studentb and Horacio Lejarraga, M.D.b ABSTRACT tension and express feelings like Traditional games have changed with the anger, anxiety or frustration, and development of technology. We analyzed dexterity games played by children and their allows children to regulate their parents in general, and jacks in particular. emotions and communicate through A survey was administered to children different behaviors, thoughts, and aged 5-12 years and their families. A total of needs. Games are a chance for 109 surveys were completed; 91.7 % of parents referred that they had played jacks and that 4.6 % children to learn, discover different of their children also played it (p < 0.00001). Girls society roles, develop abilities, and played Chinese jump rope and ring-a ring-a roses understand and take in what they less often than their mothers, but football more learn. Therefore, playing games often. Boys played ring-a ring-a roses less often than their fathers. Besides, 28.4 % of parents did also becomes a “gratifying, fun, and 3 not play any dexterity game with their children. educational activity for children.” To conclude, jacks, Chinese jump rope, and Vygotsky defined games like ring-a ring-a roses are now less common; and a “changing activity that, above girls play football more often than their mothers. Parents do not usually play dexterity games with all, encourages a child’s mental their children. -

(NOT) JUST for FUN Be Sure to Visit Our Logic Section for Thinking Games and Spelling/Vocabulary Section for Word Games Too!

(NOT) JUST FOR FUN Be sure to visit our Logic section for thinking games and Spelling/Vocabulary section for word games too! Holiday & Gift Catalog press down to hear him squeak. The bottom of A new full-color catalog of selected fun stuff is each egg contains a unique shape sort to find the available each year in October. Request yours! egg’s home in the carton. Match each chick’s 000002 . FREE eyes to his respective eggshell top, or swap them around for mix-and-match fun. Everything stores TOYS FOR YOUNG CHILDREN easily in a sturdy yellow plastic egg carton with hinged lid. Toys for Ages 0-3 005998 . 11.95 9 .50 Also see Early Learning - Toys and Games for more. A . Oball Rattle & Roll (ages 3 mo+) Activity Books Part O-Ball, part vehicle, these super-grabba- ble cars offer lots of play for little crawlers and B . Cloth Books (ages 6 mo .+) teethers. The top portion of the car is like an These adorable soft cloth books are sure to ☼My First Phone (ages 1+) O-ball, while the tough-looking wheels feature intrigue young children! In Dress-Up Bear, the No beeps or lights here: just a clever little toy rattling beads inside for additional noise and fun. “book” unbuttons into teddy bear’s outfit for the to play pretend! Made from recycled materials Two styles (red/yellow and (green/blue); if you day. The front features a snap-together buckle by PLAN toys, this phone has 5 colorful buttons order more than one, we’ll assort. -

Gopher Sport 2018-2019 Catalog GOP18

GOP18 Effective April 2018 D Stock Discounted Shipping Description UOM e Truck # Price Costs l 1 01-012 Team Spots Game System EA $159.00 $0.00 REGULAR 2 01-024 Ball Sealer Set - 1 Gallon EA $33.96 $0.00 REGULAR Rainbow ClassicCoat Coated-Foam Ball Pack One - 25 3 01-106 EA $254.15 $0.00 REGULAR Pieces 4 01-114 Adventure Course Set EA $160.65 $0.00 REGULAR 5 01-124 Rainbow Rubber Rings - 6" dia, Set of 36 EA $84.96 $0.00 REGULAR Rainbow Fox 40 Classic Pealess Whistles w/ Cushioned 6 01-166 EA $38.21 $0.00 REGULAR Mouth Grip - Set of 6 Cone Caps Station Markers - Animal Movement Set, Set 7 01-180 EA $177.65 $0.00 REGULAR of 29 8 01-181 Cone Caps Station Markers - Locomotor Set, Set of 24 EA $143.65 $0.00 REGULAR 9 01-186 Rainbow Team BucketStack Game - Set of 36 EA $84.96 $0.00 REGULAR Cone Caps Station Markers - Fitness Station Set, Set of 10 01-189 EA $135.15 $0.00 REGULAR 22 11 01-197 Shield Floor Hockey Safety Butt Ends - Set of 12 EA $21.21 $0.00 REGULAR DPE Curriculum Supplies Package for K-6 - Supplies 12 01-210 EA $8,999.00 $1,529.83 TRUCK Package 3 DPE Curriculum Supplies Package for K-6 - Supplies 13 01-212 EA $6,499.00 $1,104.83 TRUCK Package 2 DPE Curriculum Supplies Package for K-6 - Supplies 14 01-214 EA $3,799.00 $645.83 TRUCK Package 1 15 01-225 Rainbow Color-Coded Equipment Pack - 162 Pieces EA $956.25 $0.00 REGULAR Rainbow ClassicCoat Coated-Foam Ball Pack Two - 25 16 01-226 EA $339.15 $0.00 REGULAR Pieces 17 01-245 Pow'R Ball Activity Set EA $299.00 $0.00 REGULAR Active & Healthy Schools Playground Pack w/ Screamin' -

Outdoor Games You Can Do in a Pandemic

Outdoor games you can do in a pandemic Lizzy Hunt Introduction During a pandemic you may not be able to play sports with a team but there are many actives that you can play at home with your family. There are so many different games other than the ones you know, like soccer, football, baseball, and basketball. I have added some games to these slides that younger kids will like. Four Square #44 For Four Square you need to make one big square and four different squares inside the bigger square. You can make it out of blue tape or chalk. You will need to label them 1-4; you need 4+ players one in each square. I have two videos down below that will help you play. Rules and how to play: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3snA-57CiX8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_mR8yb2StA Chinese Jump Rope #34 How to play: All you need is some rope that should be around 16 feet or you can buy one on Amazon. You need either 3 people or 1 person and 2 chairs. The rope should be at the ankle of the two people and then the one person will jump. The different ways you can do it are on the two Youtube videos down below. Here are some patterns that you can learn to make it fun: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kL5EpNad9Jc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=idrr_a3EseI Games For Younger Kids ● Watch the clouds. You can see which shapes they make. ● Roll down a hill. -

PDF Catalog" Ebay App by SOMEGR8DEALS

"SOMEGR8DEALS" Catalog Visit us: http://stores.ebay.com/somegr8deals "PDF Catalog" eBay app by http://3Dsellers.com SOMEGR8DEALS We Offer Toys, Security products, C O2 products, Nano C ube lighting, Aquarium C hillers and Freshwater and Saltwater supplies. We also offer price beat policies on all JBJ Aquarium products, Milwaukee Meters. http://cgi3.ebay.com/ws/eBayISAPI.dll?ViewUserPage&userid=1000greatdeals Red TRION:Z TRIONZ Dual Lit e Oral Irrigat or: Hydro W at er Chinese Jump Rope Deluxe: Bananagrams W ord Game A Saxof lut e Quercet t i Kids A mazing Live Sea Monkeys On Magnet ic Golf Bracelet Floss Dent al Shower Jet Pik Jumping Play Toysmit h ward Musical Mars Educat ion Fish Toy Tank Toy W inning BanA nagram A Toy Saxophone/Flut e A quarium Triop Habit at nagram $19.95 $19.95 $3.48 $14.95 $11.95 $17.20 A nimal Rubber Bands: Shaped (2) Mace Gun Cat ridge Ref Mace Gun Ref ills OC + H2O (2) Mace Gun Cat ridge Ref Mace Gun: Pepper Spray Police Pepper Spray Gun: Mace Police Pet Set Bandz Fun & Silly ills: H2O Pepper Spray Ref ill Cat ridges Pepper Spray Ref ills: OC Pepper Spray Ref ill Self Def ense 25 f t St ream Self Def ense 25 f t St ream ill $43.79 $44.79 $1.50 $13.45 $19.87 $15.45 HI 991404 Hanna pH/EC/TDS Monit or W aboba Blast : W at er Ball Red: HexBug Nano Glow Dark Blue: HexBug Nano Gravit y Blue HexBug Nano Glow Dark HexBug Nano Glow in t he Dark GroChek HI991404 Pool Hex Robot ic Bug Micro Robot Hex Hex Robot ic Bug Micro St art er Set Hex Bug A rena Beach Game Bouncing Toy Robot ic Bug Micro Robot Robot $10.99 $19.97 -

Public Schools of Edison Township Office Of

PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF EDISON TOWNSHIP OFFICE OF CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION Middle School Physical Education Length of Course: ¾ Term Elective/Required: Required Schools: Middle Schools Eligibility: Grade 6, 7, 8 Credit Value: N/A Date Approved: August 27, 2018 2 Middle School Physical Education TABLE OF CONTENTS Statement of Purpose 3 Introduction 4 Archery 8 Basketball 13 Cognitive Physical Education 18 Cricket 23 Dance 26 Developmental Games 29 Floor Hockey 33 Free Weights 36 Frisbee 40 Golf 43 Gymnastics 45 Jump Rope 49 Lacrosse 53 Parachute 57 Physical Fitness 60 Recreational Games/Lifetime Sports 65 Soccer 68 Softball 71 Speedball 74 Team Handball 77 Touch or Flag Football 80 Track and Field 83 Volleyball 88 Wrestling 92 Modifications will be made to accommodate IEP mandates for classified students. 3 Middle School Physical Education STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The purpose of Physical Education is to foster participation in physical activities by applying movement concepts and skills that the students can appreciate for the rest of their life. In the process, the students will use critical thinking skills, decision-making and problem-solving skills as they relate to the middle school student and physical education. The curriculum has been contoured to meet the NJ Core Curriculum Content Standards for Physical Education and career ready practices. The activities included in this curriculum guide targets the physical, mental and social well being of the middle school student. Emphasis will be placed on developing personal attitudes, behaviors, and values in addition to addressing health-related fitness concepts and their application towards a lifetime of physical activity. Fitness activities will be performed every other day throughout the school year or included as an extension of warm ups.