Children's Folklore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friends, Enemies, and Fools: a Collection of Uyghur Proverbs by Michael Fiddler, Zhejiang Normal University

GIALens 2017 Volume 11, No. 3 Friends, enemies, and fools: A collection of Uyghur proverbs by Michael Fiddler, Zhejiang Normal University Erning körki saqal, sözning körki maqal. A beard is the beauty of a man; proverbs are the beauty of speech. Abstract: This article presents two groups of Uyghur proverbs on the topics of friendship and wisdom, to my knowledge only the second set of Uyghur proverbs published with English translation (after Mahmut & Smith-Finley 2016). It begins with a brief introduction of Uyghur language and culture, then a description of Uyghur proverb styles, then the two sets of proverbs, and finally a few concluding comments. Key words: Proverb, Uyghur, folly, wisdom, friend, enemy 1. Introduction Uyghur is spoken by about 10 million people, mostly in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. It is a Turkic language, most closely related to Uzbek and Salar, but also sharing similarity with its neighbors Kazakh and Kyrgyz. The lexicon is composed of about 50% old Turkic roots, 40% relatively old borrowings from Arabic and Persian, and 6% from Russian and 2% from Mandarin (Nadzhip 1971; since then, the Russian and Mandarin borrowings have presumably seen a slight increase due to increased language contact, especially with Mandarin). The grammar is generally head-final, with default SOV clause structure, A-N noun phrases, and postpositions. Stress is typically word-final. Its phoneme inventory includes eight vowels and 24 consonants. The phonology includes vowel harmony in both roots and suffixes, which is sensitive to rounded/unrounded (labial harmony) and front/back (palatal harmony), consonant harmony across suffixes, which is sensitive to voiced/unvoiced and front/back distinctions; and frequent devoicing of high vowels (see Comrie 1997 and Hahn 1991 for details). -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Loving Attitudes by Rachel Billington Loving Attitudes by Rachel Billington

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Loving Attitudes by Rachel Billington Loving Attitudes by Rachel Billington. ‘One Summer is a real emotional roller-coaster of a read, and Billington expertly sustains the suspense.’ Daily Mail. Available to order. One Summer is unashamedly a tragic love story. Great passion is a theme I return to every decade or so. (For example, my earlier book, based on Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Occasion of Sin.) Of course it is a theme recurring in all fiction over the centuries. In this case the man, K, is twenty four years older than his love object who is still a school girl – and a naïve school girl at that. I have, however, not just written about the love affair but about its consequences fourteen years on so that the story is told in two different time-scales. It is also told in two voices – the male and the female. Part of the book is set in Valparaiso, Chile, where I stayed with my daughter, Rose Gaete, and my Chilean son-in-law just as I started writing the novel. Chance experience always plays a big part in what goes into my novels, although my characters are virtually never drawn directly from life. ‘Writing with grace and unflinching intensity, Billington acknowledges the complexity of cause and effect in a novel that is as much about the sufferings of expiation as the joys of passion.’ Sunday Times. ‘One Summer is a real emotional roller-coaster of a read, and Billington expertly sustains the suspense.’ Daily Mail. ‘Reading One Summer is an intense, even a claustrophobic experience: there is no escape, no let up, no Shakespearian comic gravedigger to lighten the tension. -

Urban Legends

Jestice/English 1 Urban Legends An urban legend, urban myth, urban tale, or contemporary legend is a form of modern folklore consisting of stories that may or may not have been believed by their tellers to be true. As with all folklore and mythology, the designation suggests nothing about the story's veracity, but merely that it is in circulation, exhibits variation over time, and carries some significance that motivates the community in preserving and propagating it. Despite its name, an urban legend does not necessarily originate in an urban area. Rather, the term is used to differentiate modern legend from traditional folklore in pre-industrial times. For this reason, sociologists and folklorists prefer the term contemporary legend. Urban legends are sometimes repeated in news stories and, in recent years, distributed by e-mail. People frequently allege that such tales happened to a "friend of a friend"; so often, in fact, that "friend of a friend has become a commonly used term when recounting this type of story. Some urban legends have passed through the years with only minor changes to suit regional variations. One example is the story of a woman killed by spiders nesting in her elaborate hairdo. More recent legends tend to reflect modern circumstances, like the story of people ambushed, anesthetized, and waking up minus one kidney, which was surgically removed for transplantation--"The Kidney Heist." The term “urban legend,” as used by folklorists, has appeared in print since at least 1968. Jan Harold Brunvand, professor of English at the University of Utah, introduced the term to the general public in a series of popular books published beginning in 1981. -

Afsnet.Org 2014 American Folklore Society Officers

American Folklore Society Keeping Folklorists Connected Folklore at the Crossroads 2014 Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts 2014 Annual Meeting Committee Executive Board Brent Björkman (Kentucky Folklife Program, Western The annual meeting would be impossible without these Kentucky University) volunteers: they put together sessions, arrange lectures, Maria Carmen Gambliel (Idaho Commission on the special events, and tours, and carefully weigh all proposals Arts, retired) to build a strong program. Maggie Holtzberg (Massachusetts Cultural Council) Margaret Kruesi (American Folklife Center) Local Planning Committee Coordinator David Todd Lawrence (University of St. Thomas) Laura Marcus Green (independent) Solimar Otero (Louisiana State University) Pravina Shukla (Indiana University) Local Planning Committee Diane Tye (Memorial University of Newfoundland) Marsha Bol (Museum of International Folk Art) Carolyn E. Ware (Louisiana State University) Antonio Chavarria (Museum of Indian Arts and Culture) Juwen Zhang (Willamette University) Nicolasa Chavez (Museum of International Folk Art) Felicia Katz-Harris (Museum of International Folk Art) Melanie LaBorwit (New Mexico Department of American Folklore Society Staff Cultural Affairs) Kathleen Manley (University of Northern Colorado, emerita) Executive Director Claude Stephenson (New Mexico State Folklorist, emeritus) Timothy Lloyd Suzanne Seriff (Museum of International Folk Art) [email protected] Steve Green (Western Folklife Center) 614/292-3375 Review Committee Coordinators Associate Director David A. Allred (Snow College) Lorraine Walsh Cashman Aunya P. R. Byrd (Lone Star College System) [email protected] Nancy C. McEntire (Indiana State University) 614/292-2199 Elaine Thatcher (Heritage Arts Services) Administrative and Editorial Associate Review Committee Readers Rob Vanscoyoc Carolyn Sue Allemand (University of Mary Hardin-Baylor) [email protected] Nelda R. -

Lmnop All Rights Reserved

Outside the box design. pg 4 Mo Willems: LAUGH • MAKE • NURTURE • ORGANISE • PLAY kid-lit legend. pg 37 Fresh WelcomeEverywhere I turn these days there’s a little bundle on the fun with way. Is it any wonder that babies are on my mind? If they’re plastic toys. on yours too, you might be interested in our special feature pg 27 on layettes. It’s filled with helpful tips on all the garments you need to get your newborn through their first few weeks. Fairytale holdiay. My own son (now 6) is growing before my very eyes, almost pg 30 magically sprouting out of his t-shirts and jeans. That’s not the only magic he can do. His current obsession with conjuring inspired ‘Hocus Pocus’ on page 17. You’ll find lots of clever ideas for apprentice sorcerers, including the all- © Mo Willems. © time classic rabbit-out-of-a-hat trick. Littlies aren’t left out when it comes to fun. Joel Henriques offers up a quick project — ‘Fleece Play Squares’ on page Nuts and bolts. pg 9 40 — that’s going to amaze you with the way it holds their interest. If you’re feeling extra crafty, you’ll find some neat things to do with those pesky plastic toys that multiply in your home on page 27. Bright is Our featured illustrator this month is the legendary Mo the word on Willems (page 37). If you haven’t yet read one of Mo’s books the streets (and we find that hard to believe) then here’s a good place this autumn. -

Poetry Vocabulary

Poetry Vocabulary Alliteration: Definition: •The repetition of consonant sounds in words that are close together. •Example: •Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. How many pickled peppers did Peter Piper pick? Assonance: Definition: •The repetition of vowel sounds in words that are close together. •Example: •And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side Of my darling, my darling, my life and my bride. -Edgar Allen Poe, from “Annabel Lee” Ballad: Definition: •A song or songlike poem that tells a story. •Examples: •“The Dying Cowboy” • “The Cremation of Sam McGee” Cinquain: Definition: • A five-line poem in which each line follows a rule. 1. A word for the subject of the poem. 2. Two words that describe it. 3. Three words that show action. 4. Four words that show feeling. 5. The subject word again-or another word for it. End rhyme: Definition: • Rhymes at the ends of lines. • Example: – “I have to speak-I must-I should -I ought… I’d tell you how I love you if I thought The world would end tomorrow afternoon. But short of that…well, it might be too soon.” The end rhymes are ought, thought and afternoon, soon. Epic: Definition: • A long narrative poem that is written in heightened language and tells stories of the deeds of a heroic character who embodies that values of a society. • Example: – “Casey at the Bat” – “Beowulf” Figurative language: Definition: • An expressive use of language. • Example: – Simile – Metaphor Form: Definition: • The structure and organization of a poem. Free verse: Definition: • Poetry without a regular meter or rhyme scheme. -

Sodobne Povedke in Urbane Legende

Sodobne povedke: razmišljanje o »najbolj sodobnem« žanru pripovedne folklore Ambrož Kvartič Contemporary legends are an important part of the contemporary folk narrative repertoire and can provide us with vital information on processes in modern day society and culture. Th ey are frequently defi ned as an account of an unlikely event considered as factual. Th e content of these stories is oft en placed in the modern social and cultural reality. Th ey refl ect people’s attitude towards the current situation and the changes in their environment. Although traditional motifs can be recognised in contemporary legends, their context is in- fl uenced by the “modernity”. In the paper a couple of stories with their interpretations are presented, gathered in the Slovenian town of Velenje. Uvod Odkar so ameriški folkloristi v šestdesetih letih dvajsetega stoletja opozorili na tako imenovane sodobne (tudi urbane) povedke – zgodbe ki krožijo predvsem v mestnih oko- ljih in se širijo tudi s pomočjo medijev in drugih sodobnih komunikacijskih sredstev – se je v mednarodni folkloristiki sprožilo veliko zanimanje zanje. Poznavanje, tj. zbiranje, ana- liza in interpretacija sodobnih povedk, ima namreč izjemen pomen za naše razumevanje reakcij ljudi na spremembe, s katerimi so soočeni v svojem okolju. Folkloristi so v svojih analizah večkrat pokazali, kako se skozi te zgodbe (in druge žanre sodobne folklore) izra- žajo in sproščajo temeljni človekovi strahovi, frustracije, problemi, nemoč in podobno. Poglavitno vprašanje pri znanstveni obravnavi sodobnih povedk je, ali jih lahko obravnavmo in opredeljujemo kot poseben žanr žanrskega sistema pripovedne folklore in katere so tiste značilnosti, ki jih, če obstajajo, ločujejo od drugih žanrov. -

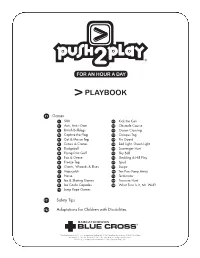

Playbook Games (PDF)

® PLAYBOOK V P1 Games P1 500 P11 Kick the Can P1 Anti, Anti i-Over P12 Obstacle Course P2 British Bulldogs P13 Ocean Crossing P2 Capture the Flag P13 Octopus Tag P3 Cat & Mouse Tag P14 Pin Guard P3 Crows & Cranes P14 Red Light, Green Light P4 Dodgeball P15 Scavenger Hunt P4 Flying Disc Golf P15 Sky Ball P5 Fox & Geese P16 Sledding & Hill Play P6 Freeze Tag P17 Spud P6 Giants, Wizards & Elves P17 Swipe P7 Hopscotch P18 Ten Pass Keep Away P7 Horse P19 Terminator P8 Ice & Skating Games P19 Treasure Hunt P9 Ice Castle Capades P20 What Time Is It, Mr. Wolf? P10 Jump Rope Games P21 Safety Tips P23 Adaptations for Children with Disabilities ®Saskatchewan Blue Cross is a registered trade-mark of the Canadian Association of Blue Cross Plans, used under licence by Medical Services Incorporated, an independent licensee. Push2Play is a registered trade-mark of Saskatchewan Blue Cross. HOW TO PLAY: Choose 1 player to be the first thrower. The rest of the players should be 15 to 20 steps away from Players the thrower. 3 or more The thrower shouts out a number and throws the ball toward the group Equipment so everyone has an equal chance of catching it. Ball The player who catches the ball gets the number of points the thrower shouted. The thrower continues to throw the ball until another player makes enough catches to add up to 500 points. This player now becomes the thrower. CHANGE THE FUN: If a player drops the ball, the points shouted out by the thrower are taken away from the player’s score. -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

2021 Summer Day Camp @ - Elkhart Elementary

2021 SUMMER DAY CAMP @ - ELKHART ELEMENTARY THIS WEEK AT THE Y WEEKLY THEME: BACK TO THE FUTURE CAMPERS & FAMILIES - WEEK OF: May 31st-June 4th NO YMCA on Monday, May 31st. Memorial Day! FIELD TRIPS & SPECIAL EVENTS: June 1st - First Day of Camp! Everyday-Please make sure to bring a Mask, Lunch, 2 Snacks, Water Bottle, Closed Toed Shoes and Sunscreen. Friday– Magic Rob SITE HOURS CONTACT US 6:30 AM—6:00 PM Director - Maria Leon [email protected] Assistant Director - Carmen VISIT US ONLINE https://www.denverymca.org/programs/youth-programs/summer-day-camp WHAT TO BRING EVERYDAY Water Bottle, Shoes w/ closed toes, Sunscreen, Lunch, AM & PM Snacks MONDAY WEDNESDAY FRIDAY TUESDAY THURSDAY 6:30-8:30 6:30-8:30 6:30-8:30 6:30-8:30 Open Camp Stations Open Camp Stations Open Camp Stations Open Camp Stations NO CAMP Coloring, Coloring 9:00 Coloring, Coloring, - CAMP Building Games Building Games - Building Games Building Games 6:30 Board Games Board Games Board Games Board Games PRE CAMP OPENING CAMP OPENING CAMP OPENING & AM SNACK & AM SNACK & AM SNACK CAMP OPENING CAMP OPENING & AM SNACK AM ROTATIONS & AM SNACK AM ROTATIONS 9:00-9:30AM 9:00-9:30AM AM ROTATIONS AM ROTATIONS 9:00-9:30AM Snack and Camp Opening 9:00-9:30AM Snack and Camp Opening NO CAMP Snack and Camp Opening 9:45-11:45 Snack and Camp Opening 9:45-11:45 9:45-11:45 Craft– Pictures Frames 9:45-11:45 Cooking– Root Beer Floats Craft– CD Disco Ball Gym– Freeze Dance Craft– Loom Bracelets 12:00 Gym– Brake Dance — Outside– Dress up Relay Gym– Double Dutch Gym– 60– Second Contest Objects -

J.A.M. (Jump and Move): Practical Ideas for JR4H Heart Links Instant

J.A.M. (Jump And Move): Practical Ideas for JR4H Chad Triolet – [email protected] Chesapeake Public Schools 2011 NASPE Elementary Physical Education Teacher of the Year www.PErocks.com www.noodlegames.net www.youtube.com/user/NoodleGames Heart Links Heart Links are a great way to make some connections for students regarding fundraising and the importance of exercise in building a strong and healthy heart. We use this activity during our Jump Rope for Heart week as a “rest station”. Students complete one heart link each class period and are asked to write down one thing they can do to be heart healthy or a heart healthy slogan. They can decorate them if they would like and then they place them in a basket so that the links can be put together. During class, we connect some of the links then talk about the links at the end of the class as a culminating discussion about the importance of fundraising and exercise. Fundraising – Sometimes a small amount of money does not seem like it makes a difference but if you use the heart chain that is created as an example, students realize that when the links are added together they make a huge chain that goes around the gym. So, every little bit of money collected, no matter how small, adds up and can make a difference. Exercise – In much the same way, daily exercise doesn’t seem like it would have a big effect on how healthy your heart can be. The visual of the heart chain helps the students understand that if you exercise each day, it adds up and builds a strong and healthy heart. -

No. 83 October 2014 ISSN 1026-1001 Newsletter of the International Society for Contemporary Legend Research

No. 83 October 2014 ISSN 1026-1001 FOAFTale News Newsletter of the International Society for Contemporary Legend Research IN THIS ISSUE: Sippurim, a collection of Jewish tales edited by Wolf PERSPECTIVES ON CONTEMPORARY LEGEND 2014 Pascheles (1847), and especially by the novel Der Golem by Gustav Meyrink (1915). The Golem legend became • A Welcome from the Organizer hugely popular in the second half of the 20th century • Abstracts when it was adopted by all city dwellers as an • A Reflection expression of local identity. Historical legends even • ISCLR and the Sheffield School surround the city’s new coat of arms, awarded to the • Prizes Awarded city by the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III in 1649 Also for valiant defense in the Thirty Year’s War. • Remembering Linda Dégh Prague has always linked East and West, not only by • Perspectives on Contemporary Legend 2015 folklore but by folklore research as well. For example, • Legend in the News the brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm greatly • New Feature: Bibliography influenced the first Czech Romantic folklorists and • Police Lore mythologists. Perhaps the most important scholar of • Plugs, Shameless and Otherwise this generation was Karel Jaromír Erben, a collector of • Contemporary Legend now Online Czech folktales and author of the first multilingual • Back Matter collection of myths and legends of the Slavonic peoples, Vybrané báje a pověsti národní jiných větví slovanských [Selected Myths and National Legends of Other PERSPECTIVES ON CONTEMPORARY LEGEND 2014: Branches of the Slavonic Nation] (1865), and the A WELCOME FROM THE ORGANIZER popular ballad collection Kytice z pověstí národních [A Bouquet of Folk Legends] (1853/1861), which was Dear colleagues, inspired by demonological legends collected in the On behalf of the local Organizing Committee of the Czech countryside (and which is now available in a Perspectives on Contemporary Legend, the 32nd beautiful new [2012] English translation by Marcela International Conference of the International Society Malek Sulak).